Despite the promise of great upland and waterfowl hunting, dear friends and a place where Ernest could escape fame and work without interruption, Mary and Papa Hemingway did not return to Idaho until the fall of 1958. During the intervening decade, Ernest spent considerable time trying to retrace and recapture his past by traveling back to France, Italy, Spain and Africa but, as he later acknowledged, “The truly good and wonderful things, you can know but once in life.” Ernest also pursued his writing while both he and Mary continued life at their home, the Finca Vigia (Lookout Farm), near Havana and fished the Gulf stream aboard the Pilar.

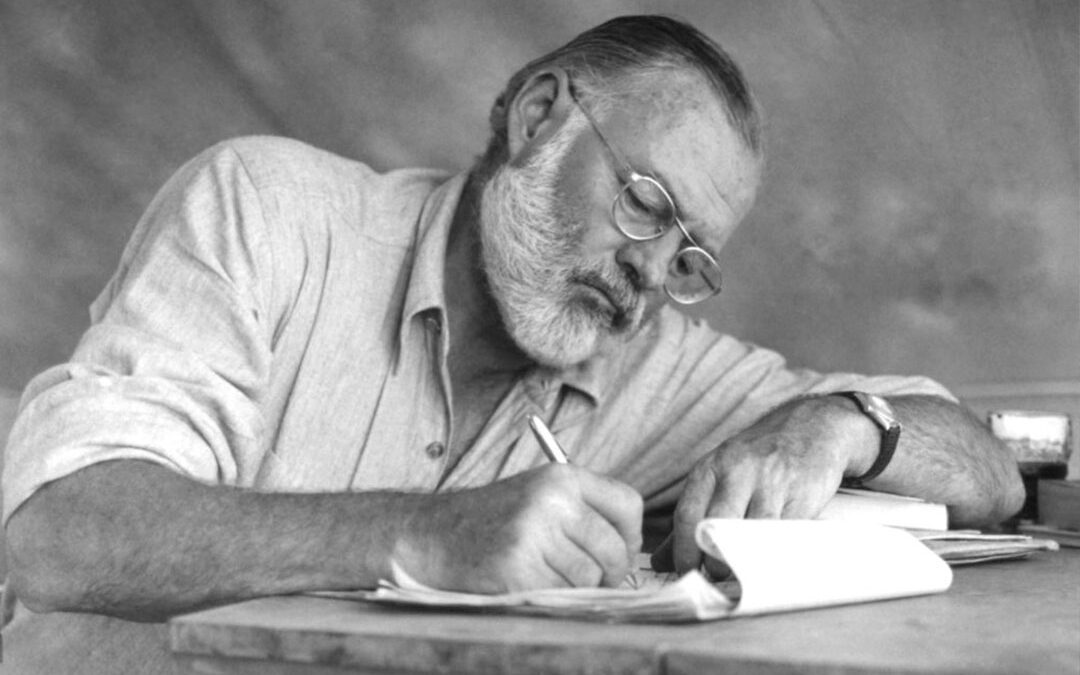

Hemingway celebrating a double on mallards taken at the Purdy ranch with his short barreled Winchester Model 12. This was the last image of Hemingway hunting. He is joined by (left to right) by Leonard “Bud” Purdy, Ruth Purdy and the former mayor of Sun Valley, William “Win” Gray.

A variety of things conspired to bring the Hemingways back to Ketchum and Sun Valley. Both he and Mary clearly missed their friends with whom they had kept up a faithful correspondence over the years. They also missed the beauty of the country, Mary once said poetically that “they missed Silver Creek with the quakers (quaking aspen) trembling gold among the pines and the smell of the sage and the wilderness of the sky and the brown velvet hills.”

Ernest was also deeply involved with a book at the time and adamant that there would be no publicity. He said that he was pestered so much with “interrupters” in Cuba that he could not work. Ernest also complained of the oppressive heat and hurricane weather and that fishing in the Gulf Stream had “gone to hell.” In addition, the slum population that had once been somewhat distant from the Finca, was beginning to encroach and there had been several burglaries recently at their home. During one such nighttime intrusion, he shot at a thief with a .22 rifle just as he was escaping through the bathroom window. They found a blood trail the next morning on the outside terrace, but fortunately no body.

Ernest Hemingway poses with a Cape buffalo in Africa, 1953-1954.

During the late 1950s, the political situation in Cuba was also beginning to deteriorate and relations with the United States had cooled considerably after Fidel Castro came to power in 1959. Hemingway left Cuba for good in July of 1960 and by that fall, Fidel Castro had expropriated all assets and properties owned by Americans, including the Finca Vigia. Ernest knew that he could no longer return to Cuba and that he would have to abandon their home of 20 years, his beloved Pilar and most of their personal possessions.

Some years after Hemingway’s death, a special arrangement between Castro and President Kennedy enabled Mary to return to the Finca and reclaim many of their personal effects, including valuable art work and manuscripts. The author’s house has more recently undergone some much-needed renovations and both it and the Pilar, which is dry docked nearby, are an ersatz museum and tribute to Cuba’s adopted and most famous escritor.

Hunting & Shooting in Idaho

Bird hunting remained the primary draw for Ernest upon his return to Idaho and there were still ample numbers of upland birds to hunt in the nearby fields and numerous ducks to pursue along Silver Creek. However, unlike hunting during the war years, there were considerably more hunters afield in the area and many of the places they had hunted in the 1940s no longer belonged to the original farmers or ranchers they had befriended.

Ernest is serving as a columbaire by hand launching a magpie for a guest at the “Silver Creek Rod and Gun Club” near Picabo, Idaho, circa late 1950s.

Fortunately, there were still enough places owned by people they knew so that they could be assured of hunting on private land and well away from the hordes of hunters “infesting” the area. In addition to pheasants and grouse, there was also a new upland game bird to hunt. Chukar, which Ernest had first enjoyed hunting in Spain, were introduced in Idaho in 1950. The birds thrived in the steep rocky terrain, and the first bird season was held in 1953. Ernest considered them to be among the best tasting game birds and, despite the rugged country that chukar typically inhabit, he nonetheless enjoyed the opportunity to hunt them—even if it meant leaving the roughest country to younger legs.

It should also be mentioned that during this time he was always careful about never mixing alcohol with gunpowder. Drinking was generally reserved for after the hunt and often during post-hunt picnics. Papa loved picnics in general, but especially after an invigorating day in the field. Friends and fellow hunters would gather for a bonfire, food and drink, regardless of weather or temperature.

One of the more interesting pastimes he enjoyed during this period was shooting magpies. At the time, there was still a bounty on these birds because they were considered a menace to ground nesting birds such as pheasant, grouse, partridge and quail. Ernest’s rancher friend, Leonard “Bud” Purdy, constructed traps that he baited with sheep carcasses to catch the birds and many local farm boys made extra pocket money by trapping the birds as well. Intrigued by their challenging, erratic flight, Ernest came up with the idea of having live bird shoots, somewhat reminiscent of the live pigeon shoots that he enjoyed in Cuba at the Club des Cazadores and around Europe.

Ernest Hemingway, Clara Spiegel and Gary Cooper, Silver Creek, Idaho, January 1959.

For the Silver Creek shoots, individual birds were taken from a gunny sack and launched by hand. The shooter was often flanked by two backing shooters who fired only if the primary shooter missed with his allotted two shots. Ernest and his shooting friends, which included Gary Cooper, Jimmy Stewart, Lloyd Arnold, Bud Purdy and once even the Shah of Iran, made quite the social occasion of it with plenty of spectators, defined shooting rules, trophies, wagering and abundant food and wine. Hemingway, who was noted for being a very keen wing shot, was often the high shooter at these events. One year the group presented him with a Magpie Trophy, which sat proudly on his desk at his house in Ketchum. The shooting was done at a private cabin along Silver Creek, which he and his friends jokingly called the “Silver Creek Rod & Gun Club.”

He also enjoyed trap shooting behind the house he and Mary purchased in April of 1959. Ernest had inherited several thousand clay pigeons from the previous owner and he was quick to locate a hand trap and organize an informal shooting squad. Lloyd Arnold and Ernest’s friend and physician, Dr. George Saviers, among others, would often drop by during lunch three or four times a week and launch clays off the high hill overlooking the Big Wood River. The shooting was competitive, wagers were made and Ernest generally walked away with both the accolades and the money.

He preferred a simple hand trap because it allowed for significantly more variation in the trajectory of the clay pigeons than a mechanical trap. It must have taken him back to his boyhood days at the family cottage, “Windemere,” in northern Michigan where he and his father would shoot clays every Sunday afternoon. It was miraculous to see how clay shooting took him from being a lonely, withdrawn old man back to the boyish, enthusiastic person he used to be. He became completely immersed in the friendly competition and banter that usually accompanies such occasions. It was clearly a tonic for Ernest and he kept his passion for both clay shooting and bird hunting until the very end of his life.

Papa’s Last Hunt

On November 12, 1960, Papa joined Lloyd Arnold at Bud Purdy’s cattle ranch in hopes of jumping some local ducks known to be in the area. Papa was in the lead, stuffing shells into his Winchester Model 12 pump gun as they snuck up on the old south irrigation canal running sluggishly through the grazing land. It was his second Model 12 shotgun, which he bought from a bellboy at Sun Valley because he said his original one had worn out. Given the innumerable shells that he ran through his old Model 12 since it was purchased in 1928, and the shape it was in when he first came to Sun Valley in 1939, that was probably not an understatement.

Ernest and Mary take a break after a successful day hunting.

His new shotgun was a short-barreled affair that Lloyd charitably called “plain damn ugly” and Ernest called his W.D. (Whore’s Dream) gun. On the muzzle sat a bulbous and ungainly experimental Flex-Choke device that would tighten automatically from improved cylinder to modified and then to full choke with the gas from each successive shot. It could also be set at a specific choke by twisting a lock collar. Despite its ugliness, it was both quick and deadly in Hemingway’s hands and he used it to good effect.

Just as he racked a shell into the chamber, the metallic sound of the action closing spooked three unseen mallard drakes that were hugging the near bank. The ducks sprung up well within range and Papa, with the speed and accuracy honed from a lifetime of wingshooting with a pump shotgun, neatly took a double. He then tried for the third mallard, but by that time it was winging well out of range. As fate would have it, this was Papa’s last successful hunt.

Such keen gun handling, remarkable for a man of his age and physical condition, was a fitting end to a hunting career that spanned from his childhood days in Illinois and Northern Michigan to Europe, Africa and finally to a field in central Idaho.

“How kind it is that most of us will never know when we have fired our last shot.”

— Nash Buckingham Letters to John Bailey, George Bird Evans, 1984

The Death of an Icon

The final decade of Hemingway’s life had wrought profound physical and mental changes upon him. The famous grey bearded man who returned to Idaho in the fall of 1958 was no longer the barrel-chested epitome of virility. He was overweight, had dangerously high blood pressure and was recently diagnosed with liver and kidney disease, anemia, hemochromatosis, arteriosclerosis and vision problems. He also suffered from alcoholism and periods of impotency and there were personality changes and indications that his once remarkable memory had begun fading.

![]()

By late 1960, the unrelenting torment of depression, paranoia, his failing health and his damaged memory had made his life a living hell with no respite and nothing to look forward to. He could no longer write, he could not return to Cuba and he would not return to the Mayo Clinic to suffer again the indignities and futility of more electroconvulsive therapy. Nor could he allow himself to be committed to a mental institution. For a man who was devoted to living life on his own terms, the continuous torment his life had become, and the bleak future that awaited him, left very little in the way of options.

On the morning of July 2, 1961, Mary was awakened in their Ketchum, Idaho, home to what, in her sleep-fogged mind, appeared to be the sound of “a couple of drawers banging shut.” She went downstairs to find “a crumpled heap of bathrobe and blood with Ernest’s favorite 12-gauge W.& C. Scott & Son Monte Carlo B Pigeon side-by-side shotgun lying in the disintegrated flesh in the front vestibule of the sitting room.” A truly ignoble ending for one of the world’s best-known writers and most iconic sportsmen.

There are a multitude of reasons why Hemingway decided to end his life. Certainly, his inability to write, short and long-term memory loss, clinical depression, failing health, paranoia and alcoholism are all plausible reasons. More recently, chronic traumatic encephalopathy (CTE) has also been suggested as an underlaying cause of his suicide. CTE is a degenerative brain disease typically associated with professional boxers and football players, which results from repeated injury to the brain. Individuals with CTE may show cognitive impairment, impulsive behavior, memory loss, diminished executive function, emotional instability, anger, dementia and suicidal behavior. Interestingly, Hemingway describes such an individual in his 1925 short story The Battler, when he meets Ad Frances, a former boxing champion. Hemmingway sustained at least nine significant concussions and one serious cranial fracture that we are aware of and that does not include brain injuries which may have resulted from playing football and boxing.

![]()

Lastly, there is a strong familial or genetic component to consider. There have been six known or attempted suicides in the Hemingway lineage. Ernest’s maternal grandfather and namesake, Ernest Hall, attempted suicide with his Civil War-era .32-caliber pistol, but was unsuccessful because his son-in-law, Clarence, Ernest’s father, had removed the cartridges. Ironically, Ernest’s father later used the same pistol to take his own life in 1928. Following his father’s death, Ernest prophetically announced that “I’ll probably go the same way.”

Ernest’s younger brother, Leicester, also shot himself in 1982. His sister, Ursula, died from a drug overdose in 1966 and his granddaughter, Margaux, died of a barbiturate overdose in 1996. In all, four family members from four generations succumbed to suicide, and mental illness is seen in at least five successive generations. Whether it was bad genetics or the physical and cognitive price of having lived an accident-prone and often destructive lifestyle, fate finally and irrevocably caught up with Ernest. In the end, we can only speculate on which factors, either singly or collectively brought Hemingway to his violent and untimely demise.

Ernest Hemingway at his home in Cuba, circa 1953, standing in front of the 1929 portrait of himself by Waldo Pierce.

Ernest Hemingway was among the best known and most respected authors of the 20th century. He was an iconoclast, and his spartan, sinewy prose influenced a generation of writers. He was also recognized internationally as an avid sportsman and his public persona, which he was careful to cultivate, typified him as the quintessential hard drinking, pugilistic, womanizing alpha male. His passing marked the end of an era in both a literal and literary sense.

Hemingway is buried in the quaint Ketchum, Idaho, cemetery that is watched over by the Sawtooth Mountains to the north. He rests between two evergreens that his fourth wife, Mary, planted there after his death. His grave marker, a simple granite slab, is often covered with coins, beer cans, liquor bottles, wine glasses, shotgun shells, bullets, cigars and other ephemera left by people who still remember him and admire his writing. He rests for “all the seasons that will ever be” next to Mary and they share the grounds with Ernest’s eldest son, Jack, granddaughter, Margaux Hemingway, and many of his dearest friends including Lloyd and Tilley Arnold, Bud Purdy and Dr. George Saviers.

“And now he has come home to the hills. He has come back now to rest well in the country that he loved through all the seasons.”

— E.M. Hemingway

This article originally appeared in the 2020 May/June issue of Sporting Classics.