Ernest Hemingway is inextricably linked to both Sun Valley and the nearby town of Ketchum, Idaho. He had a special affinity for the countryside with its backdrop of the Sawtooth Mountains, which reminded him of Spain, for the excellent bird hunting he found there and for the local people who disregarded his celebrity and, in many respects, became his extended family.

Sun Valley, which lays just two miles northeast from what had once been the prosperous and populous mining and ranching town of Ketchum, was established in 1936 with the building of the Sun Valley Lodge. This project was the brainchild of Averell Harriman, chairman of the board for the Union Pacific Railroad, and was intended to be among the nation’s first and finest Western ski resorts.Harriman was acutely aware that to make this venture viable he needed publicity for the area’s many year-round activities. A publicity agent by the name of Gene Van Guilder and a photographer named Lloyd Arnold were hired for the job. Both men figured prominently in Hemingway’s life and both were responsible for attracting Hemingway to the area, along with a host of A-list celebrities such as Gary Cooper, Bing Crosby, Clark Gable, Jane Russell and Lucile Ball.

Ernest left the Nordquist L-Bar-T Ranch in the Clark’s Fork Valley of Wyoming where he spent part of the fall and arrived at Sun Valley in September of 1939 in his black Buick convertible. Sitting next to him was a svelte, attractive blonde named Martha (Marty) Gellhorn, an ambitious journalist he’d met by accident a few years earlier at Sloppy Joe’s bar in Key West. Several years after their initial meeting, they met up in Madrid where they were both war correspondents covering the Spanish Civil War. With his marriage to his second wife Paulene Pfeiffer on the rocks, Ernest and Marty began carrying on a torrid and rather thinly veiled affair.

By the time he arrived in Sun Valley, Ernest was already considered to be among the most influential writers of his generation. His notable literary accomplishments to date included: The Torrents of Spring, 1926, The Sun Also Rises, 1926, A Farewell to Arms, 1929, Death in the Afternoon, 1932 and The Green Hills of Africa, 1935.

At 41, Ernest was in his physical and literary prime and had been voted America’s Number One “He Man.” He also described himself as being “flat-ass broke” at the time and interested in a solution that would enable him to remain in the West to continue his writing and hunting. Harriman offered Ernest free use of the guest facilities at the lodge for two years in exchange for some publicity photographs and endorsements.

Hemingway enjoyed teaching neophytes to shoot. Here, he’s hunting with starlette Jane Russell (circa 1947), a task that was undoubtedly to his liking.

Several things drew Ernest to Sun Valley, aside from his generous living arrangements with his mistress and the opportunity to bird hunt. Sun Valley provided a much-needed hiatus from the humid, hurricane-ridden weather of autumn in Cuba. The surrounding country immediately reminded him of the Sierra de Guadarrama mountain range north of Madrid and it even had a resident population of Basque sheepherders, whom Ernest was particularly fond of.

Ernest also liked the local Western culture because he was not treated like a celebrity. Most locals cared little for the fact that he was an internationally renowned author and tended to judge him strictly on his merits as a man.He also needed a place where he could hole up and work without interruption on his current novel, For Whom the Bell Tolls. He completed the novel in 1940 and the following year sold the movie rights for $150,000, which was a record at the time and brought a much-needed infusion of cash.

A successful family pheasant hunt in the fall of 1941 near Dietrich, Idaho. Left-to-right: Martha Gellhorn, Ernest and children, Jack, Gregory and Patrick Hemingway.

Talk with Van Guilder and Arnold on that autumn morning naturally turned to hunting and fishing. Ernest admitted that he was not interested in trout fishing because he felt it was too time consuming. Many people believe that he avidly fished for trout while he was there, when in fact the only fish he ever caught were for a publicity photograph. Even big-game hunting was of secondary importance, although in subsequent years he and his family hunted mule deer, antelope and elk in the surrounding area.

What he was truly interested in was bird hunting. Van Guilder and Arnold told Ernest about the phenomenal pheasant hunting on the nearby ranches and of hunting large numbers of ducks on the meandering waters of Silver Creek. They made plans to reconnoiter the area for game and their opening season hunts were eagerly anticipated.

Tragically, Van Guilder died Sunday Oct. 29, 1939 on the Snake River. Arnold was paddling in the stern with Van Guilder in the bow and a third hunter named Dave Benner sitting amidships. Gene had spied a small group of ducks on the water and stood up to take a shot at the tightly bunched flock. Neglecting a cardinal rule in jump shooting—that only the person in the bow has a loaded shotgun—Benner also fired at the ducks just as Van Guilder lost his balance. The shot charge caught Van Guilder just below the right shoulder blade. The wound was mortal, and he passed away shortly thereafter in the yard of a nearby farm.

Gene’s wife asked Ernest, who was not hunting that day, if he would prepare a eulogy for her husband and what resulted was perhaps the finest final tribute that any sportsman could ask for. Ironically, an excerpt from the eulogy would be placed on a memorial to Ernest erected in 1966 on an overlook by Trail Creek near Sun Valley. The memorial bears a bronze bust of the author and carries an inscription that reads: “Best of all he loved the fall/The leaves yellow on the cottonwoods/Leaves floating on the trout streams/And above the hills/The high blue windless sky/Now he will be part of them forever.”

Ernest and Marty were put up comfortably in room 206 at the lodge, which he later nicknamed the Glamour House because of all the celebrities who had stayed there. As was his habit throughout much of his writing career, Ernest arose around 5 a.m. each day and worked on his writing until 10 or 11 a.m. He then liked to spend the remainder of the day away from the desk and in the outdoors where he could shoot or hunt.

That fall, Ernest worked on his latest novel from that room and on the balcony, and even made a brief reference to Sun Valley in the book. The suite, which is the most requested one at the lodge, can still be rented today. Although it has undergone numerous renovations over the years, its mountain view and the Hemingway mystique remain.

Soon after arriving in Idaho, Ernest was anxious to settle in and remove the firearms he had brought from their leather cases, lest they begin to rust. As he was unpacking, he showed Lloyd his Winchester Model 12 shotgun. The Model 12 was ubiquitous among serious American shotgun hunters at the time, and Lloyd told Ernest that he also owned one. What he did not say was how shocked he was at the condition of Ernest’s shotgun.Lloyd later told his wife Tillie that the shotgun was a sight for “sorry eyes.”

While working the action, Loyd said “it rattled like a corn-sheller and its action was loose as a goose.”

Ernest was a fan of Marvel Mystery Oil and tended to use it to excess, which was obviously the case with his Model 12. Gun oil had settled into the grip of the stock, which was split where it butted the metal and was so loose it was about to fall off.

“If I’d seen that gun in a pawn shop, I wouldn’t have paid ten dollars for it,” Loyd said.

Seeing the attention Lloyd was paying to the shotgun, Ernest replied, “I’ll bet your Model 12 isn’t as beat-up as this one.”

Lloyd mentioned that the stock was a bit loose, Ernest replied, “Yeah, we gotta tighten her up, Chief. I couldn’t operate without this old stopper.”

Ernest shoulders his 6.5mm Mannlicher Schoenauer carbine mentioned in The Short and Happy Life of Francis Macomber.

Ernest also brought along a 12-gauge Browning Superposed over-and-under that he was very proud of because he had won it several years earlier from a well-known shooting champion at a live bird shoot in France. He also uncased a .30-06 Springfield rifle built by Griffin & Howe in 1930 that he wrote about in the Green Hills of Africa and a 6.5x54mm Manlicher-Schoenauer rifle that belonged to his estranged wife, Pauline, and that he described in The Short and Happy Life of Frances McComber.

A couple of .22 plinking rifles, one of which was most likely his pump-action Winchester Model 61, completed his personal arsenal.

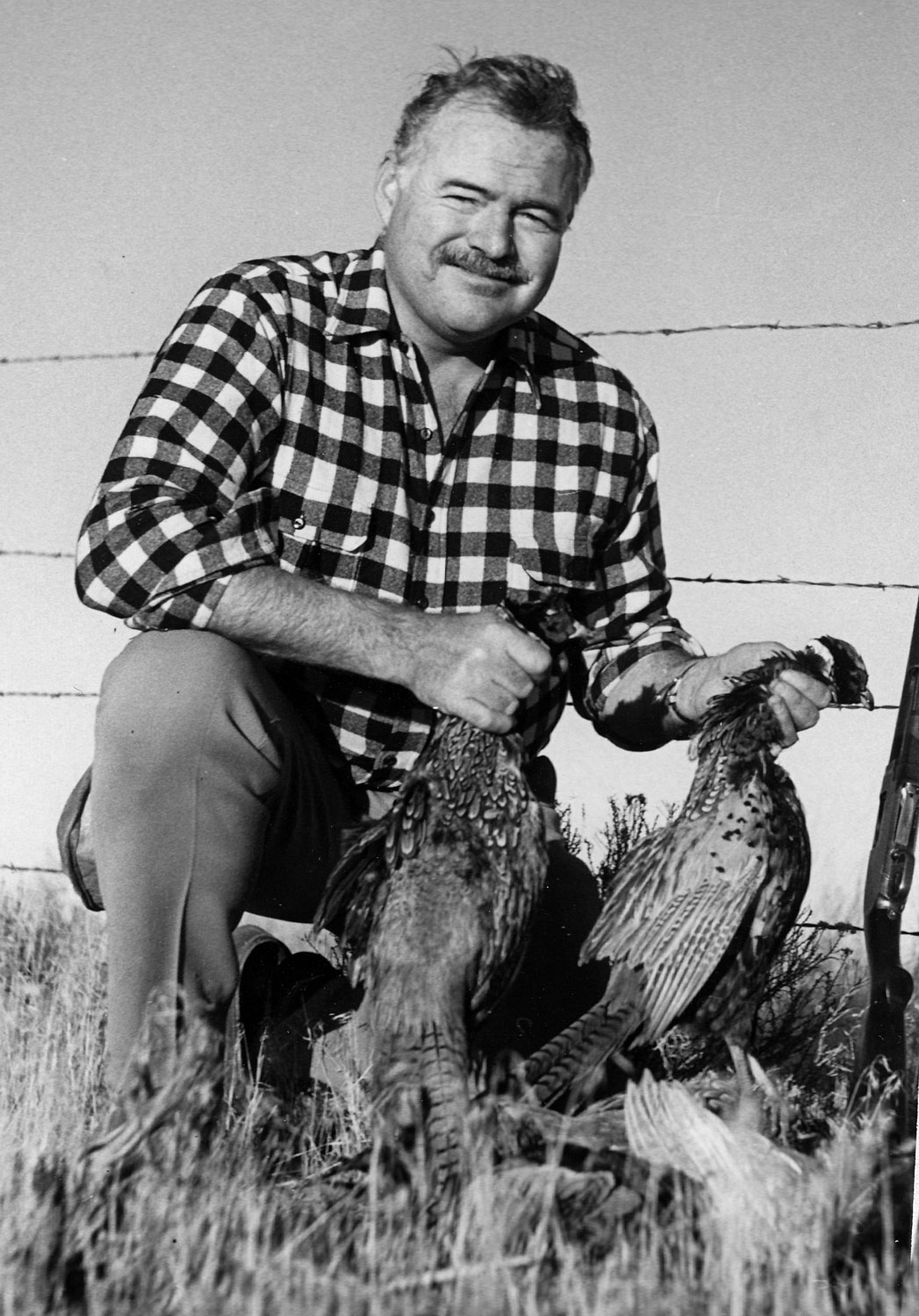

Photographs of Ernest hunting often show him and his friends beaming at one another while clutching large bouquets of ringneck pheasants or plump northern mallards. Although Ernest always wore glasses, very few images show him actually wearing them. Perhaps he took them off in a nod to vanity, because you can occasionally see him holding them while the pictures were being taken.

During his time in Idaho, Ernest always looked forward to the opening of pheasant and duck season like a kid waiting for Christmas. His connection to area ranchers through Lloyd Arnold and head Sun Valley hunting guide Taylor Williams assured that he would always have plenty of private hunting lands available to him. It is important to note that although pheasants were his primary upland quarry, there were many other indigenous and introduced gamebirds to hunt in the surrounding fields, hills and sagebrush. These included doves, Hungarian partridge, quail, snipe and several species of grouse.

It was a bird shooter’s nirvana when Ernest first arrived, and the hunting continued to improve during the war years when shotgun shells became scarce and costly, fuel rationing began in 1942, and most of the able-bodied men were off fighting the war. When he was not hunting or writing, Ernest also played some tennis to appease Marty and shot trap at the Sun Valley Gun Club.

Ernest was by all accounts a very gregarious bird hunter and thoroughly enjoyed inviting along numerous family, friends and even mere acquaintances to share in the hunt and post-hunt festivities. He also enjoyed organizing pheasant and rabbit drives and picked up the moniker “The General” because of the near military precision with which he organized drives and his carefulness in avoiding intersecting lines of fire.

One notable jackrabbit drive was conducted on the Frees Farm in 1941 near Dietrich, Idaho. The drive, which must have occurred near the peak of the rabbits’ population cycle, accounted for close to 2,200 “jacks.”

Another notable “hunt” that year took place in Ernest’s suite at the lodge. He was still in his pajamas and lathered up to shave, when he heard the resident geese in the pond below his room begin to call. Throwing open the French doors to the small balcony, he saw a pair of Canada geese winging toward the lodge at eye level. One of the birds was clearly wounded, so he quickly found his shotgun and two loads of No. 2 shot that he kept in his hunting jacket as coyote medicine. He then proceeded to cleanly drop both birds from inside his room.

Marty, who was in another room and unaware of the proceedings, was understandably startled by the gunfire and burst into Ernest’s suite, wondering if he’d shot someone. Ernest took a lot of good-natured ribbing after that for hunting from what was probably the world’s most plush and expensive goose blind.

Numerous people who hunted with Hemingway during the 1940s point out that he was very considerate in the field, often allowing others to take the first shot or positioning people to better advantage. During that time, Ernest hunted with both Clark Gable and Gary Cooper.He was also photographed in the field hunting with two of the most beautiful starlets of the time, Ingrid Bergman (who starred alongside Gary Cooper in the 1943 film adaptation of For Whom the Bell Tolls), and Jane Russell, a task that I am certain was very much to his liking.

Ernest and Gary Cooper, or “Coop,” as he was known to many, struck up a friendship that lasted until Cooper died from prostate cancer in May of 1961, just seven weeks before Ernest would take his own life.

He once said of his longtime friend: “Cooper is a fine man: as honest and straight and friendly and unspoiled as he looks.”

Marty joined Ernest on many of his hunts, but she once confided to Lloyd Arnold’s wife, Tillie, that she only tagged along to please her husband and that she had no interest whatsoever in either guns or hunting.

Conversely, Ernest’s children—Jack (Bumby), Patrick (Mouse) and Gregory (Gigi), who went on some of their first bird hunts while in Sun Valley and took full advantage of the excellent hunting and fishing opportunities in the area. Gregory, the youngest, was by far the most accomplished shot. At the Club Cazadores in Cuba, he competed in live pigeon shoots and trapshooting and regularly outshot most grown men. His prowess with a shotgun was an attribute that Ernest was immensely proud of.

By early November of 1940, Ernest’s divorce from Paulene was finalized and he married Martha later that same month in Cheyenne, Wyoming. Although there were certainly some happy times in Cuba and Idaho, their relationship soon began to fray. Ernest, it seems, was deeply resentful about playing a distant second to Martha’s journalism career. She once told him somewhat prophetically: “Be advised, love passes. Work alone remains.”

Martha’s frequent absences as a foreign war correspondent for Collier’s Weekly Magazine once prompted Ernest to send her a cable asking: “Are you a war correspondent or wife in my bed?”

A turning point in his marriage to Martha came in 1944. Hemingway offered his byline to Collier’s as their war correspondent and the publisher readily accepted the famous author over Martha. It was a professional and personal insult to Martha and calculated to suppress her career. By guile and determination, she made it to Europe by crossing the Atlantic aboard a ship filled with high explosives and tracked down Ernest in London where he was hospitalized due to a concussion sustained in a car accident. Unsympathetic to his condition, she told him she was “through, absolutely finished.”

The divorce between Ernest and Martha was finalized in 1945, but in true Hemingway fashion, he had already become infatuated with Mary Welsh, a young, petit and pretty correspondent for Time, Life and the Daily Express. When the war ended, he and Mary returned to Cuba and in March of 1946 she became the fourth and final Mrs. Hemingway.

Ernest and Mary returned to Sun Valley in the fall of 1946, with an unplanned three-week detour to Casper, Wyoming, where Mary underwent emergency surgery for an ectopic pregnancy. She credited Ernest with saving her life because he managed to infuse her with plasma and reverse her shock from blood loss. The surgeon had already removed his gloves, fearing that the surgery would kill her in her current condition and told Ernest to say his goodbyes to his new wife.

When Ernest returned to Sun Valley in 1946 with his new bride, he was physically different from the man who left Idaho just a few years previous. He had gained a considerable amount of weight and, at 220 pounds, he had a noticeable paunch. His hairline was receding and perhaps more ominously, he was diagnosed with liver damage and dangerously high blood pressure. The latter was significant enough that his physician placed him on a diet, curtailed his drinking and forbade him from hunting in the mountains for deer that year.

Following Mary’s recuperation, she and Ernest actively hunted pheasants, ducks, quail and partridge with Lloyd and Tilley Arnold, the Hemingway boys and many of their close friends and acquaintances. Mary, who sprang from a rural logging town in the lake country of north-central Minnesota, learned quickly how to broil, roast and stew all the wild creatures they collected over the fall. Unlike Martha, she was determined to become a huntress in her own right and became proficient with shotgun and rifle, even managing to harvest her own deer in subsequent seasons.

Ernest and Mary were particularly fond of jump-shooting ducks from their canoe on Silver Creek near the town of Picabo. Mary had a difficult time steering when Ernest was in the bow because the differences in their weight caused the stern of the boat to stick comically up out of the water.

In the fall of 1946, an interesting incident occurred that nearly cost Ernest his life. Ernest, Mary and Nancy “Slim” Hawks were returning from a successful outing with a nice bag of partridge. Ernest had invited the New York socialite and fashion icon to Ketchum to escape the gossip columnists who were hounding her over an adulterous affair.

While returning to Ketchum, Ernest suddenly stopped the Lincoln he was driving when he spotted a Hungarian partridge in the field. Both Mary and Slim piled out of the car while loading their shotguns in hopes of adding one more bird to the bag. The bird flew off and so they headed back at the car. Slim sat on the fender of the car and ejected two shells out of her 16-gauge Browning “square back” autoloader. Believing that the chamber was empty, and not wanting to leave the shotgun cocked, she pulled the trigger. Ernest had just knelt to fix his hunting boots when the gun fired, sending a load of birdshot sailing just behind his head. The muzzle blast was so close that it singed the hair at the base of his skull.

Ernest was livid and stood up abruptly, ready to lash out. Slim shrieked in horror with the realization of what she had done and immediately began to cry. That blunted Ernest’s anger and he attempted to console her by making light of the near miss and telling her that the shotgun itself was unsafe. But everyone recognized how close to tragedy they had come that afternoon.

Ernest ended up trading her automatic shotgun for an over-and-under that he explained was safer for her (and Ernest). Describing the incident to a friend in a letter, he concluded: “So what are a few burned hairs off the back of the neck for a piece of loot like that.”

During his early years in Idaho, Ernest was at the very pinnacle of his physical and intellectual powers. Sun Valley and Ketchum provided a much-needed respite from Cuba, a place where he could write without intrusion and enjoy hunting and shooting pastimes, passions he’d loved since childhood. The local people were not impressed by his international celebrity and accepted Hemingway and his wives and girlfriends at face value. They integrated him into their social structure and, in many regards, became a surrogate family to him.

In the winter of 1948, Ernest and Mary returned to Cuba from where they embarked on a series of trips to Europe and Africa. They believed they would be away for only two years at most, but a full decade passed before they returned.

The tumult of the ensuing decade brought considerable change to Ernest both personally and professionally and he was a changed man when he returned once again to Idaho in the fall of 1958.

This article originally appeared in the Spring 2020 issue of Sporting Classics Magazine. Photos courtesy John Fitzgerald Kennedy Library, Boston.