And “charged” with life is exactly what he means.

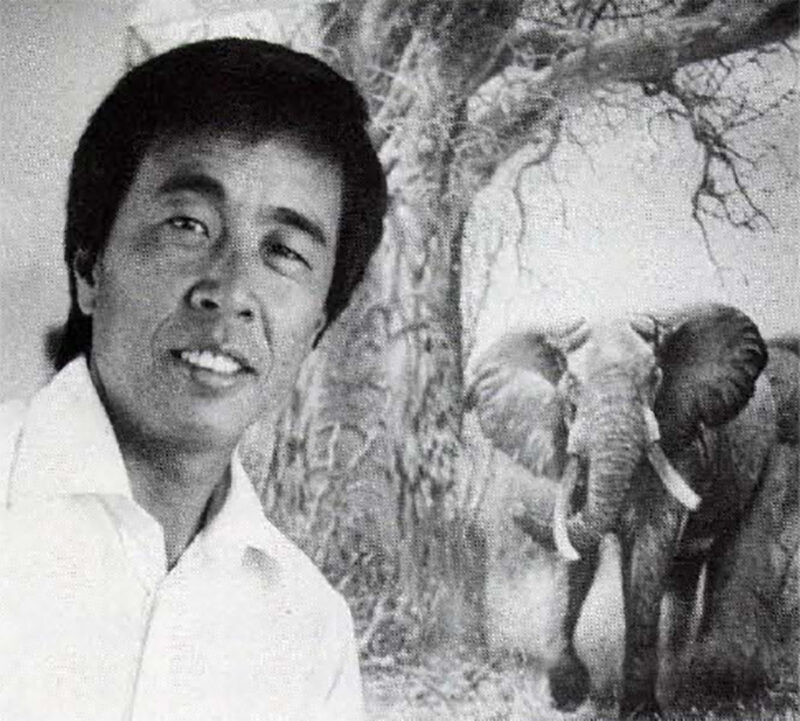

Incredibly, he has had no formal art training, yet he is considered by many to be among the world’s best wildlife artists. He considers himself a cultural orphan, whose life experiences span three continents and include dramatic escapes from death by sharks and execution.

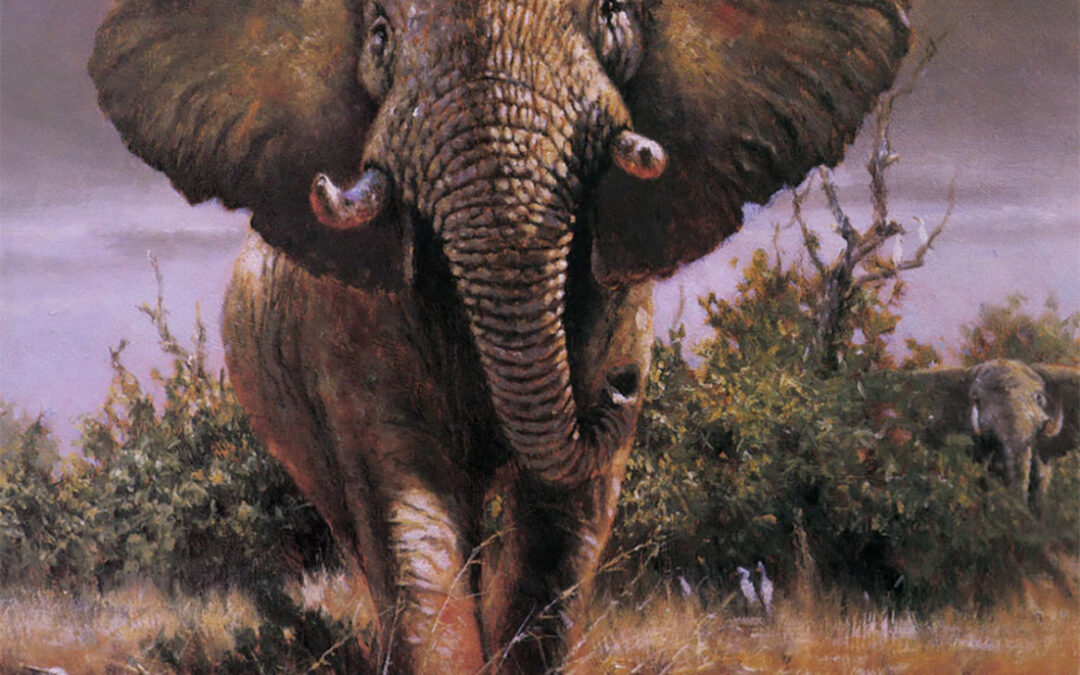

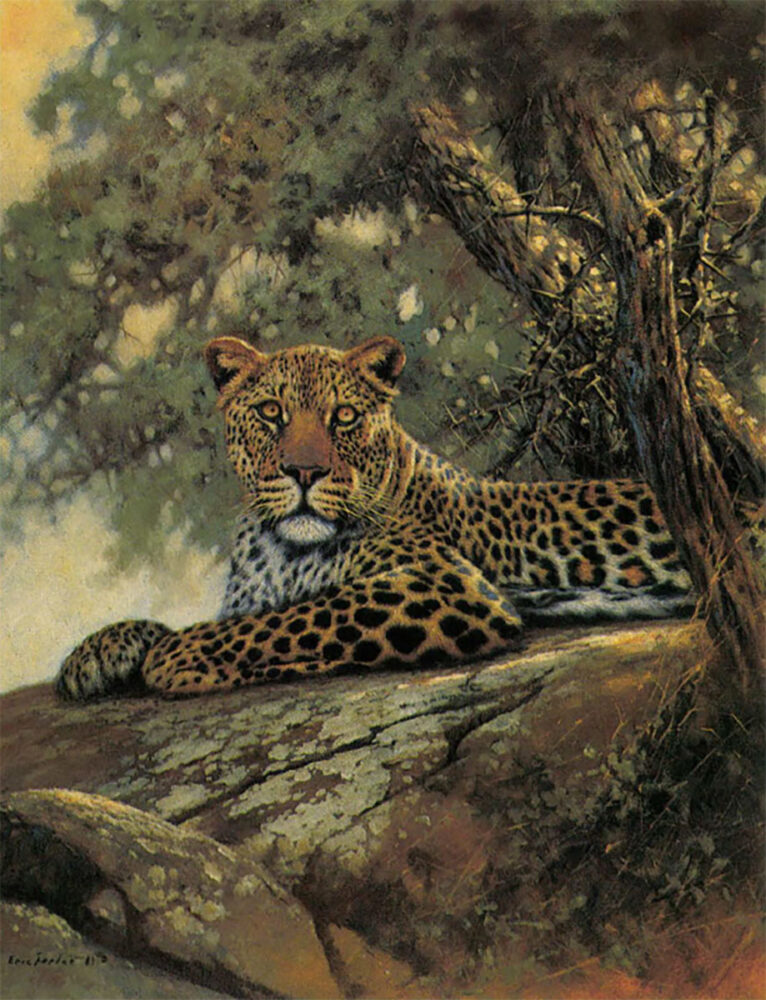

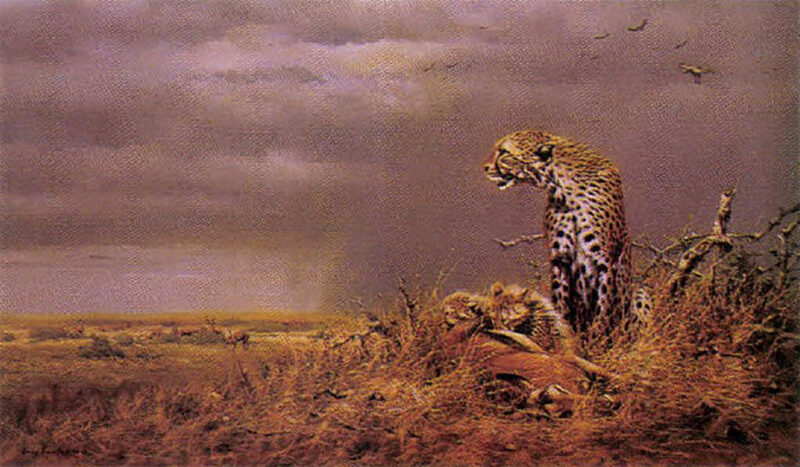

Eric Forlee’s oil paintings of African wildlife are prized by hunters, animal lovers and art collectors. His work “captures the essence of Africa,” says Herbert Hazen of the Charles d’Lou Wildlife Gallery in Jackson, Wyoming. “He depicts the true animal. If you haven’t seen a leopard in the wild, you probably can’t relate. Probably 85 percent or more of the people who buy his paintings have been to Africa and/or understand the relationship of animals to the beautiful background of his work.”

Eric Forlee’s oil paintings of African wildlife are prized by hunters, animal lovers and art collectors. His work “captures the essence of Africa,” says Herbert Hazen of the Charles d’Lou Wildlife Gallery in Jackson, Wyoming. “He depicts the true animal. If you haven’t seen a leopard in the wild, you probably can’t relate. Probably 85 percent or more of the people who buy his paintings have been to Africa and/or understand the relationship of animals to the beautiful background of his work.”

Born in China in 1949, Forlee’s youthful artistic talents were suppressed by Communist authorities. After spending several years in a labor camp, he escaped to Hong Kong, worked odd jobs, got married, and finally moved his young family to Zimbabwe in 1981. It was there, after a 15-year hiatus from art, that he began painting, first landscapes and then wildlife.

Forlee’s comfortable home in Davis, California, is a world away from the hardships of his early years in China and Hong Kong. He believes his new life in the United States is an example of the rewards available to those who persist.” It doesn’t matter how long or how bad a situation is, if you keep on working you can make it,” he says.

Forlee’s father left China for South Africa before he was born, and his mother followed when he was six. Eric spent his childhood and teen years with his grandmother and uncle in a China that was left culturally bankrupt by the Communist party.

“The communists abolished all tradition. The new society created much frustration, and the people passed the frustration on to their closest ones,” Eric says, explaining the ill treatment he suffered at the hands of his relatives.

“They [the communists] treat the people so cruel that the people think that cruelty is the right thing to do. It becomes so normal.”

Eric received only six years of formal schooling, and much of that was interrupted by moving from one part of the country to another. “I could draw artistically when very young. From three or four years old, I would use chalk or brick to draw on concrete floors. When I went to school, my exercise book was full of sketches — human figures, trees, birds, buildings — whatever I wanted to draw.”

Eric received only six years of formal schooling, and much of that was interrupted by moving from one part of the country to another. “I could draw artistically when very young. From three or four years old, I would use chalk or brick to draw on concrete floors. When I went to school, my exercise book was full of sketches — human figures, trees, birds, buildings — whatever I wanted to draw.”

But at 14, he was approached by a teacher who told him he was an enemy of the people because his parents lived abroad, and therefore, he was not allowed to do any drawing. “I was taken to the principal ‘s office, and he told me ‘if you don’t stop drawing, you could disappear.’ I stopped because I knew he was serious.”

Forlee’s family had lived for several generations in South Africa. His paternal grandfather returned to China and used money earned in South Africa to purchase land. He was executed by the communists, simply because he was a landlord.

Since his parents resided in Africa, Eric was a constant suspect in the communist system. When the Cultural Revolution and its routine slaughter of artists, intellectuals and intelligentsia began in 1966, Eric, still a teenager, was among thousands sent to hard-labor camps for “reeducation.”

For a few years he attempted to work within the program, but grew to realize that the entire system was devised to create imbalance, to pit husband against wife, mother against child. “If you don’t produce enough, you are chastised as an enemy of the people. If you work too hard, you are suspected of sabotage,’ Forlee says.

For a few years he attempted to work within the program, but grew to realize that the entire system was devised to create imbalance, to pit husband against wife, mother against child. “If you don’t produce enough, you are chastised as an enemy of the people. If you work too hard, you are suspected of sabotage,’ Forlee says.

“They want everyone to be scared and want each person to watch the other, to report enemy activity. For so many people, this kind of happening is daily. I decided I had to leave the country.”

The camp was not fenced, but passes were necessary to move from one place to another. Eric and four companions forged passes with a sweet potato they carved into a “rubber” stamp. After passing the guards, they began a 400-mile journey to the sea and Hong Kong.

The men traveled by bus the first 350 miles, then walked from Kan Ton to the ocean, moving by night and hiding by day, eating potatoes and carrots stolen from fields. It took them almost three weeks to cover the last 50 miles.

Only 30 to 40 percent of those attempting to escape Red China made it to freedom. Escapees were easily recognized by their dirty, haggard condition, and trigger-happy guards in restricted zones along the way didn’t hesitate to shoot them.

Only 30 to 40 percent of those attempting to escape Red China made it to freedom. Escapees were easily recognized by their dirty, haggard condition, and trigger-happy guards in restricted zones along the way didn’t hesitate to shoot them.

To reach Hong Kong island, Eric and his friends drifted eight miles by holding onto inflated tubes. Their frightening swim had to be made at night so they could avoid detection by guards in gunboats. Only Eric and one companion arrived safely; he believes the other three were attacked and eaten by sharks.

Forlee remembers the episode as being lost in black, empty space — becoming devoid of all rational thoughts or feelings. “You’re not yourself in this situation. You lookup, it’s dark. You look around, it’s dark, and your feet don’t touch anything. Then you feel something moving under you — a big object — and you don’t know what it is. I was in terror!”

Once on shore, the Hong Kong police picked them up and offered aid. For Forlee, Hong Kong meant a chance to capture lost time.

“When I got to the free world, I felt angry that I had lost so much time. For six years in a labor camp, I had no books, no newspapers, no reading or writing,” he recalls.

He went to work in a bookstore. With his first month ‘s salary he bought a tape recorder, a dictionary and a typewriter. When his employer learned that Eric was spending evenings studying English, he was fired.

“It seems somehow I knew what I would be. People would laugh at me when I would use the typewriter. I knew that one day I would be different, so that’s why I tried to learn anything handy or useful.”

In Hong Kong he was joined by his future wife, who he had met through her brother in the labor camp. Their first two children were born in Hong Kong. He did not resume his artwork. “Since I’d put it down for so long, I didn’t know I had talent. I never thought about making a living with it.”

Forlee performed odd jobs in Hong Kong — deliveryman, cleaner, carpenter, cook, construction worker — until he had enough money to visit his parents in South Africa.

“For some reason, I instantly loved Africa,” he says.

“When I went to visit my parents, I decided at that time I wanted to come back. I was touched by Africa — not a remote feeling — but a yearning in my whole system.

“When I went to visit my parents, I decided at that time I wanted to come back. I was touched by Africa — not a remote feeling — but a yearning in my whole system.

“All my feeling comes from this … A feeling so strong that drives me to go in that direction. Not to be a wildlife artist… I just want to live in Africa.”

Racial quotas prohibited Forlee from moving his family to South Africa. So he chose Zimbabwe, entering the country in 1981 when the white government of Rhodesia was moving out to make way for the new black leadership.

Forlee made the move before his wife and children, finding work at a supermarket in the capital city of Harare where he delivered groceries on a bicycle. A relative in the city, an art teacher, took Forlee under her wing and soon discovered his interest in art.

“She gave me oil paints and a canvas, and I painted a landscape. She said it was quite good and took it to a gallery. They reluctantly accepted it.”

To his surprise, the painting brought him $60, more than his monthly salary at the supermarket. He began to paint evenings and weekends. By the time his wife and children arrived in Harare six months later, Eric was making a living with his art.

To his surprise, the painting brought him $60, more than his monthly salary at the supermarket. He began to paint evenings and weekends. By the time his wife and children arrived in Harare six months later, Eric was making a living with his art.

“In 1982, I tried to start painting wildlife, but it was awful, horrible. I truly loved wildlife, but I had no understanding of it. So I stopped painting for a year and studied African animals.”

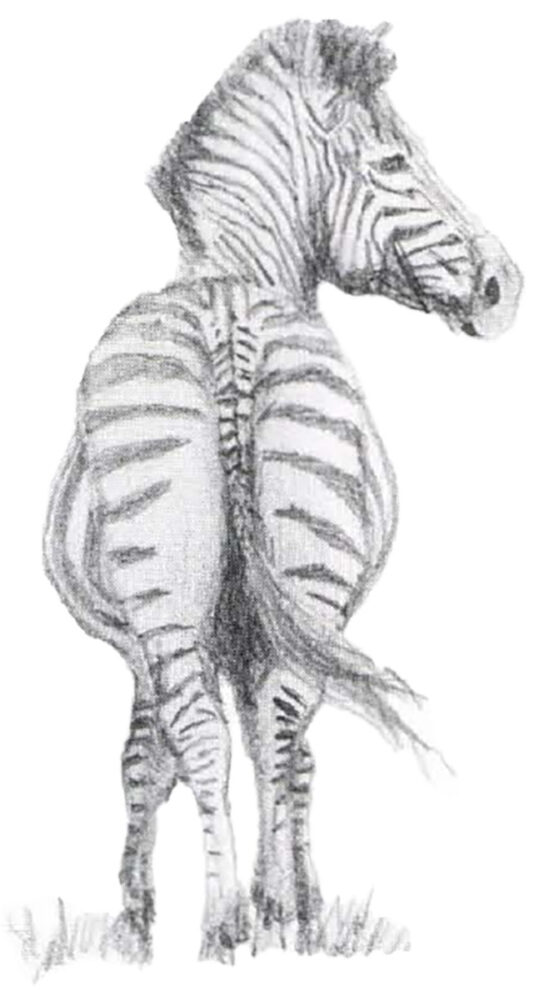

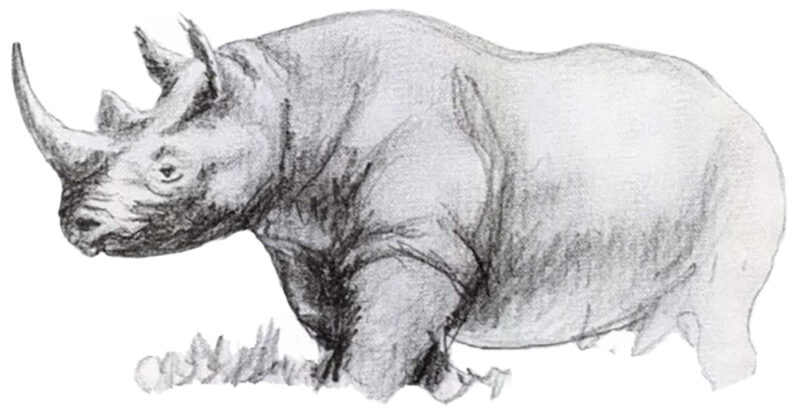

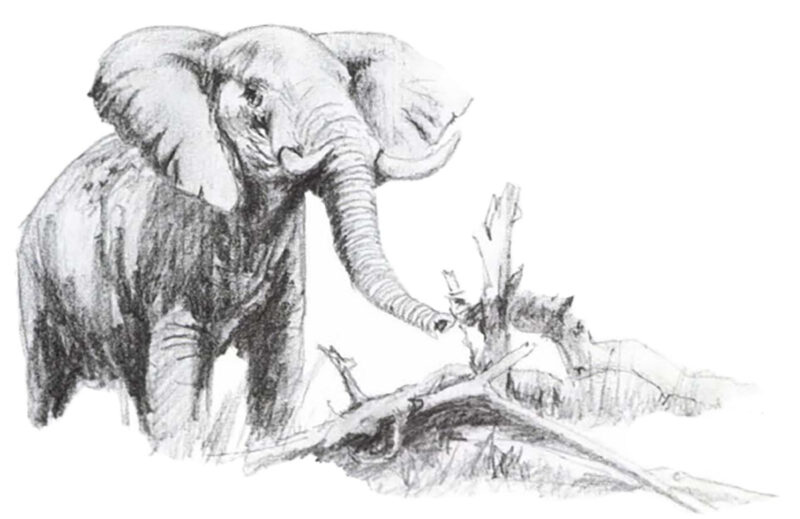

He spent a year in Zimbabwe’s national parks and game reserves, observing animal behavior and habitat; photographing and sketching zebras, giraffes, sable, wildebeests, lions, leopards, and elephants — all part of the majestic beauty that is Africa.

“I learned the animals’ proportions; that’s what you think is important at first. Then it becomes more than that. You don’t just see the proportions, but the entire animal, its manner and personality.

“You feel this excitement and you make them alive through your creative hand. You want to give yourself pleasure and give others pleasure. There’s something important there. I must let other people know what I feel.”

After a year of studying, he resumed painting wildlife.'” started to make an income from my wildlife paintings, and it opened a door for me. It was totally an accident. I just wanted to support my family and get a free style of life.”

During a trip to a game reserve, Forlee met an American who suggested that he show his work at a Safari International convention in the U.S. Eric took his paintings to the Las Vegas convention in 1985, but without much success. He spent $5,000 on the trip but did no better than break even.

He returned the following year, however, and sold every painting on display. In 1987, he stopped selling his work in Zimbabwe and concentrated on the U.S. market. And in 1989, with the help of a publisher friend, Eric and his family emigrated to the states where they made their home in Davis.

“Here you have a stable government, a stable economic and foreign policy. There is more opportunity and future for my children. Here, there is respect for human life,” he says.

Having been persecuted by the Chinese government and discriminated against by both black and white Africans, Forlee sees the American people as friendly, open and accepting.

“People say I should be proud to be Chinese. What’s to be proud of in China today? Poverty? Communism? I want to work to revive the Chinese spirit of old.”

Forlee supported the student uprising at Tiananmen Square, in spirit and financially. He is critical of communist policies in China. “China is my first country, but they didn’t give me anything but punishment. So I’m very ready to sacrifice myself for my second country — America.”

Davis, California, is a quiet college town filled with peaceful residential streets linked by bike trails. Nearby, verdant farmlands provide test grounds for researchers at the University of California campus, the primary source of employment in Davis. A few miles away almond orchards back up to rolling hills where cattle and deer share waterholes.

Forlee and his family enjoy Davis, but the artist insists that he must return to Africa periodically to commune with the animals. Painting mostly from memory, occasionally referring to photographs for detail, Forlee relies on face-to-face encounters with wild animals to infuse his paintings with a living spirit.

“You have to experience the wild before you work. You can’t just study photos — or your work will be dead, static. You can tell a good painting or bad painting by whether it is charged with life or not.”

And “charged” with life is exactly what he means. In Africa he has been charged several times by elephants. Eric says this type of life-threatening experience gives him an adrenaline rush that stays with him for months, bringing vivid emotion to his paintings.

Twice he narrowly missed being trampled. Once he escaped by jumping over an eroded riverbank. A second time, while canoeing on a river, the current helped him escape an enraged bull elephant.

“We approached and he started toward us. He splashed water up in the air like a curtain. I could see his trunk and it still makes me excited.”

Herbert Hazen describes Forlee’s work as “extremely realistic.” Says Hazen: “It’s very detailed, but it’s not tiringly detailed. Some people paint every hair on an animal, and you get tired of looking at it. Eric’s work doesn’t do that.”Forlee, who admits to being moody, has a varied work schedule. Some days he’ll paint from dawn till midnight, other days he will work only a few hours. He is a perfectionist and will sometimes take months to complete a painting to his satisfaction.

“Every painting, when I finish it, I hang on the wall, so I have a lot of time and opportunity to look at it when I’m relaxing. So, when I look at it, I can easily tell the good parts and bad parts that need to be improved.”

He begins by covering the canvas with a generous coating of thick white or light-yellow paint. He then draws the outline of the animal with pencil or linseed oil. He seeks to tell a story through his paintings, creating his backgrounds from a combination of imagination and eye-pleasing color schemes.

“If you look at this cheetah,” he says, describing a painting in progress, “his body language tells you he is stalking his prey, a very common scene in the bush. People look at this and recall their experiences in Africa.”

“To fulfill my life, I want to create something that people will appreciate long after I die. When I was in the communist camp, I dreamt about it. I wished I could do something important.”

Forlee’s art is displayed at the Americana Gallery in Carmel, California, and the Western Wildlife Gallery in San Francisco. Two limited edition prints of his work are being sold by Wolfe Publishing Company of Prescott, Arizona, and four others are available through Peterson Publishing Company in Los Angeles.

“A lot of people see a quietness in my work — background scenery that’s gentle and very quiet. Oriental art can spiritual. I don’t try to make anything harsh. I want to portray a natural way, a gentle way.”

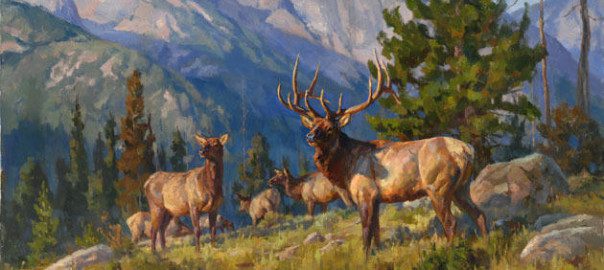

Forlee shies away from scenes of predators attacking their prey, focusing instead on wildlife in motion, often groups of animals against the backdrop of a vast plain. An African influence is also evident in his use of colors — backgrounds of soft yellows, pinks and oranges that reflect the colors of an African sunset.

Eventually, Forlee hopes to build a studio in Montana or Wyoming. He admits his current working situation — in a poorly lighted, low-ceilinged garage where paint fumes linger in the air — is undesirable. In Africa, his studio was also in his home, but wildlife and the African countryside were easily accessible.

Ultimately, Forlee is driven by his love of wild animals. “African wildlife,” he says, “is one thing in my life that I will always deeply love. I hope my talent will continue to do justice to these beautiful creatures.”

These tales from the old masters and the contemporary voices of African hunting will allow you to relive your own travels or fuel the desire to visit places not yet seen. They are more than words on a page—they are an inner look into some of Africa’s greatest hunters pursuing its legendary game animals. The stories in this book are from writers who define hunting literature. Writers whose stories will live beyond the sunset. Buy Now

These tales from the old masters and the contemporary voices of African hunting will allow you to relive your own travels or fuel the desire to visit places not yet seen. They are more than words on a page—they are an inner look into some of Africa’s greatest hunters pursuing its legendary game animals. The stories in this book are from writers who define hunting literature. Writers whose stories will live beyond the sunset. Buy Now