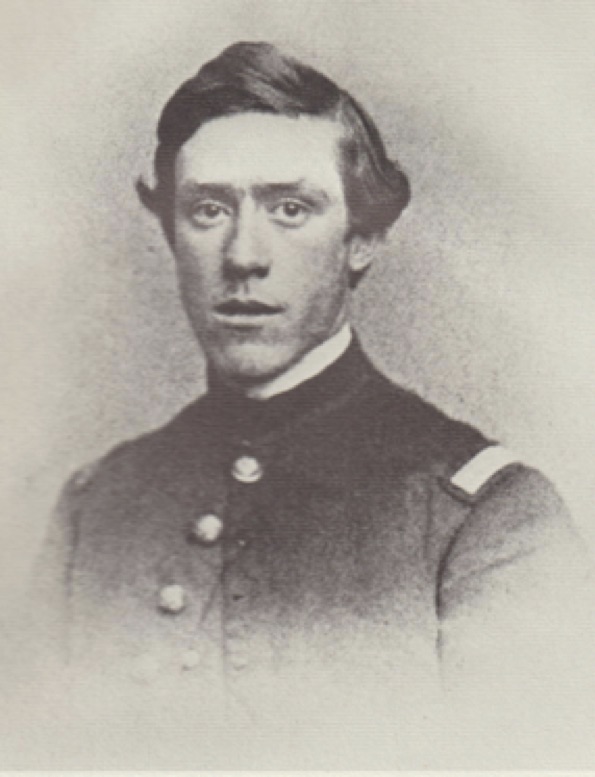

He came to the southwest as an Army surgeon, self-described as having hair on “neither lip or chin, and barely dry behind the ears.” Arriving on horseback in Santa Fe June 14, 1864 and to his post at Fort Whipple near Prescott, Arizona, July 29, he was saddle sore but eager to commence his duty as a physician specializing in surgery. The Apache Wars were on and he reported to his patron, Spencer Baird at the Smithsonian, “We are fighting the Apaches continually. A regular part of my business for two years was the extraction of Apache arrow-heads. The arrows used by the tribes nearest us were as exactly as (Zebulon) Pike describes, though so far as my observation went, the heads were all of stone, quite small and sharp, and very brittle, so that they usually shivered when they struck a bone and the fragments were not easily removed. They were only held in place with gum in the shallow notch of a hardwood stick that was set in the large reed, and thus were always left in the wound when the stick was pulled out.”

Trained as an ornithologist by Baird, he was always aware of the avifauna nearby so that he recognized a Phainopepla, appropriately feathered funeral black when, “It was growing dusk; the scene the camp of a scouting party returning from unsuccessful pursuit of some Indians, who had raided and run off our beef, and men gathering for burial the charred and dismembered body of a comrade, who had been killed and burned a few days before on that very spot, where the wolves had afterward fought for the remains. The bird of omen, for good or bad, appeared in somber cerements, and sang such a requiem as touched every heart; the camp grew more quiet than usual, and went to bed early.”

Although Elliott Coues is by far best known as an ornithologist, having written many monographs on individual species, his Birds of the Northwest, and Birds of the Colorado Valley are still recognized as benchmark works. But he was also a well-rounded naturalist as indicated by Synopsis of Reptiles and Batrachians of Arizona and the Quadrupeds of Arizona. Later in life he took on the monumental task of editing the Journals of Lewis and Clark, adding an immense amount of anthropological and natural history insight, much of which he gained by traveling their route in 1872-1874.

Although Elliott Coues is by far best known as an ornithologist, having written many monographs on individual species, his Birds of the Northwest, and Birds of the Colorado Valley are still recognized as benchmark works. But he was also a well-rounded naturalist as indicated by Synopsis of Reptiles and Batrachians of Arizona and the Quadrupeds of Arizona. Later in life he took on the monumental task of editing the Journals of Lewis and Clark, adding an immense amount of anthropological and natural history insight, much of which he gained by traveling their route in 1872-1874.

His hunting was admittedly incidental to bird collecting, yet even so he harvested bison in the Dakotas, wolves, coyotes, red, swift and kit foxes, and his encounter with a wolf in Arizona was particularly exciting. “With nothing but mustard seed in my gun, I hardly expected to more than frighten the beast, but he was so near that he rolled over quite handsomely, his hind-quarters paralyzed with a charge that took effect in the small of his back.” Among the larger mammalian specimens that he acquired was a grizzly bear that a scouting party to which he was attached killed on Bill Williams Mountain. And, the bugle of elk deeply moved him, “…the shrill sonorous whistle heard in the wilds of the West, in the stillness of the early dawn, before the first breath of day stirs, has always reminded me of a giant Aeolian harp played upon by a storm.”

He was very widely respected in the scientific community and almost universally so by his comrades at arms in the U.S. Army, but he quarreled with Major Marcus Reno to the point that Coues challenged Reno to a duel on June 5, 1874! Fortunately, for Coues at least, the duel was not held.

He was a very acute observer of wildlife and he began to see the effects of the growing human population on the local wildlife. He wrote that “Both naturalists and hunters distinguish two species of deer in Arizona, called the Black-tailed and the White-tailed. Of these, the former is by far the most abundant and characteristic; although, judging from accounts formerly given of it, it has considerably decreased in numbers owing to the persecution to which it is subjected so constantly from both the native tribes and the white settlers. It is…also called the Mule Deer, from the length of its ears…This deer forms no small share of the food and clothing both of the Indians and white settlers” (Davis 2001:172).

What about “his” deer, the Coues deer?