Perhaps a little judicious application of elbow grease would give me an opportunity to hunt elk with a real elk rifle.

Would I like to clean up a rusty old double rifle for him, Ray McKnight had casually asked over the telephone. Aware that “cleaning” can easily go too far, I replied that I’d like to see it the next time he came up to his summer home in the White Mountains of eastern Arizona. His summer home is on the edge of the Mogollon Rim, which is also home to a large herd of elk. Perhaps a little judicious application of elbow grease would give me an opportunity to hunt elk with a real elk rifle.

Ray arrived in late spring with a percussion double rifle by Thomas Kennedy of Kilmarnock, which is a bit southwest of Glasgow, Scotland. When Ray uncased the eight-pound double, it looked as if it had been on many a red deer hunt in the damp Scottish highlands and needed some gentle cleaning inside and out.

Following Ron Peterson’s instructions in the Society of American Arms Collectors Bulletin 59 (1988), removal of surface rust showed a fierce tiger engraved on the left lock and a stag on the right. Most of an hour invested on the bores revealed them to have what is generally known as Forsyth rifling: wide, shallow grooves; very narrow lands; and a twist of 1:120 inches. This rifle would hunt elk…if I could be blessed to draw another permit in Arizona.

I phoned Jamie Andrews at Dixie Gun Works and requested that he make a .665 round-ball mold. Next, I phoned Ross Seyfried and asked where to start with a powder charge. Ross surprised me with his answer: two and a half to three drams! What, in a veritable cannon that conventional wisdom says surely ought to want four to five drams? We’re talking Forsyth slow twist and a 16-bore patched ball in a gun with one standing and three leaf sights!

“Death of the Royal Stag with the Queen Riding up to Congratulate His Royal Highness,” by Sir Edwin Landseer.

I started with four drams of Cleanshot; an over-powder, 16-bore, .135-inch hard-card wad; and a Bore-Butter-lubed .015 patch, but I couldn’t hit the two-foot-square target only 50 yards away! Backing off to three drams, I got one ball from the left barrel near the right-outside edge of the six-inch black and the right barrel six inches high and crossed 11 inches to the left.

Well, why ask his advice if you don’t take it? OK, Ross, we’ll try it your way. I loaded two and a half drams of Cleanshot and got snake eyes one inch apart out to 75 yards. A dozen more groups shot off cross sticks never landed more than three inches apart. This rifle would hunt all right, but not loaded like I expected a Forsyth to be loaded. Perhaps all those extra leaf sights had a purpose after all. Once again, black-powder guru Ross Seyfried came through with the right load.

Permit 388 of 425, a rifle-hunt bull elk tag for November 24-30 in eastern Arizona’s Unit 1, soon arrived in the mail, and I began to query other elk hunters about where to set up an ambush. A site was chosen where a saddle funnels elk down into a broad meadow they are known to favor.

The Kennedy is equipped with a cap/patch box that holds components for a reload. It was loaded from an original Dixon flask.

Leaving camp at 5:25 a.m. in lightly insulated camo clothing, I was quite warm after walking 1.3 miles to the blind, which I settled into at 6:05. By 7:30 I had cooled off a lot; by 8:05 I was shivering, but I dared move no more than my eyes when I heard the telltale clatter of hoofs on rocks as two large animals moved up the steep hillside toward the saddle.

The lead bull looked like a keeper. He was followed by a large-bodied spike, and although “we don’t eat antlers,” as the country song has it, “size matters,” so I opted to try for the lead bull. It stepped up into sight, paused for breath, looked right at me, and then bent down to graze. I squeezed and held the trigger on the left lock, eased back the hammer, and aimed just behind his right shoulder.

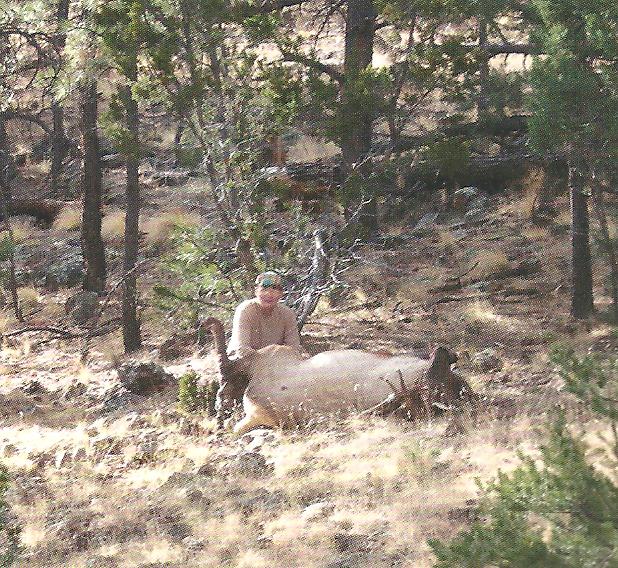

I had practiced this movement of aiming and firing offhand many times, knowing full well that the gun would shoot high at close range, which later measure showed to be only 33 paces. But in my excitement I shot higher than I wanted to—about six inches below his spine, a very high lung shot. Even so, the 448-grain, .665-caliber round lead ball collapsed him in his tracks. He fell over on his right side with his feet uphill, bled out, and died.

Then the work began. I tagged and eviscerated (“gralloched” in Gaelic) the bull, then walked back to camp and found that my son already had it packed up and was waiting to know if I’d been successful. We were able to back my little pickup close enough to tie onto the bull and pull it up over a very large Ponderosa pine limb, tie it off, and then back under it. God is very good to me!

The animal is shown where he fell, 33 paces from the blind. In honor of the Kennedy rifle’s Scottish origins, the author wears his “Celtic camouflage” flat cap.

Origins of the Kennedy

I was understandably curious as to the origins of this fine European double, but a look in Col. Robert E. Gardner’s Small Arms Makers showed only: “Kennedy, maker of sporting rifles, Kilmarnock, Scotland, 1837-1841.” Having at hand a copy of David Baker’s lovely The Royal Gunroom at Sandringham, I hoped to find mention of Kennedy therein. However, the only gunmakers I could find associated with Prince Albert were George and John Deane; J.D. Dougall; William Greener; Charles Lancaster; John Manton; and William Moore. I remain curious as to how many other makers had “MAKER TO HRH PRINCE ALBERT” on their top ribs, as does the Thomas Kennedy double rifle.

This is Michael McIntosh’s classic book on fine shotguns, in a fully revised and expanded form–covering gunmakers who have become prominent since the first edition was published in 1989 and McIntosh’s continued research into the nature of the shotgun and the people who make them.

This is Michael McIntosh’s classic book on fine shotguns, in a fully revised and expanded form–covering gunmakers who have become prominent since the first edition was published in 1989 and McIntosh’s continued research into the nature of the shotgun and the people who make them.

McIntosh divides his nearly encyclopedic gathering of gun knowledge into two distinct sections. The first is devoted to the best shotguns ever made in America, “American Best,” looks at each of the finest guns made in the United States during the Golden Age of gunmaking. Names from the past such as Parker, A. H. Fox, L. C. Smith, Ithaca, Lefever, and others are treated in greater detail, including newly manufactured American classics that bear those same names.

In the second section, McIntosh explores the revivified world of gunmaking abroad–in England, Spain, Italy, and elsewhere, places where traditional craftsmanship and modern technology have combined to make the turn of the twenty-first century the most vibrant and exciting period in fine gunmaking in nearly a hundred years. Buy Now