Mention the word “legendary” in connection with big game hunters and hunting literature, and thoughts of most serious readers likely turn in one of two distinct directions. Most will look back to the wealth of books produced by the pioneers who sampled and savored the riches of Africa during the 19th and early 20th centuries. Such individuals are represented by mighty Nimrods I profile in my recently published book, Lords of the Veldt and Vlei: Africa’s Pioneer Hunters. Among them were icons such as William Cornwallis Harris, Sir Samuel White Baker, Frederick Courteney Selous and Theodore Roosevelt. For a smaller number of readers, their thoughts will turn to the professional hunters of the 20th century, particularly those who wrote books or have had books written about their exploits.

Such men richly merit primacy of place when the word “legendary” begins to be tossed about, but there is a third group of hunters who merit inclusion as well. Admittedly they had advantages far exceeding those of the pioneers and even the great PHs. Those advantages came in forms such as convenience and ease of travel to Africa, the financial wherewithal to hunt in comparative comfort and sometimes even luxury, expertise of the first order when it came to guides and trackers, the finest guns and equipment modern technology and deep pockets can provide and more. These considerations notwithstanding, it takes a special individual, one driven by the spirit of the quest, possessed of dogged determination and willingness to make the extensive efforts necessary to achieve vaunted status among contemporaries, to earn such plaudits. Elgin T. Gates (1922-1988) was such a man.

Gates was born in Salt Creek, Wyoming, certainly a suitable setting for the making of mighty hunter. After all, Wyoming is our least populous state, a place of open spaces, abundant game, staunchly independent people and rich hunting traditions. Unsurprisingly, because it was true of most Wyoming youngsters then and blessedly remains so in considerable measure still, Gates grew up hunting from a young age, first in Wyoming and, in adolescence, in Colorado. He would grow up to be what more than one individual has described as “the greatest hunter of the 20th century.” Such evaluations are always open to debate, but without question he merits the description legendary and has the credentials to place him squarely in the top ranks of the big game hunters of the past hundred years.

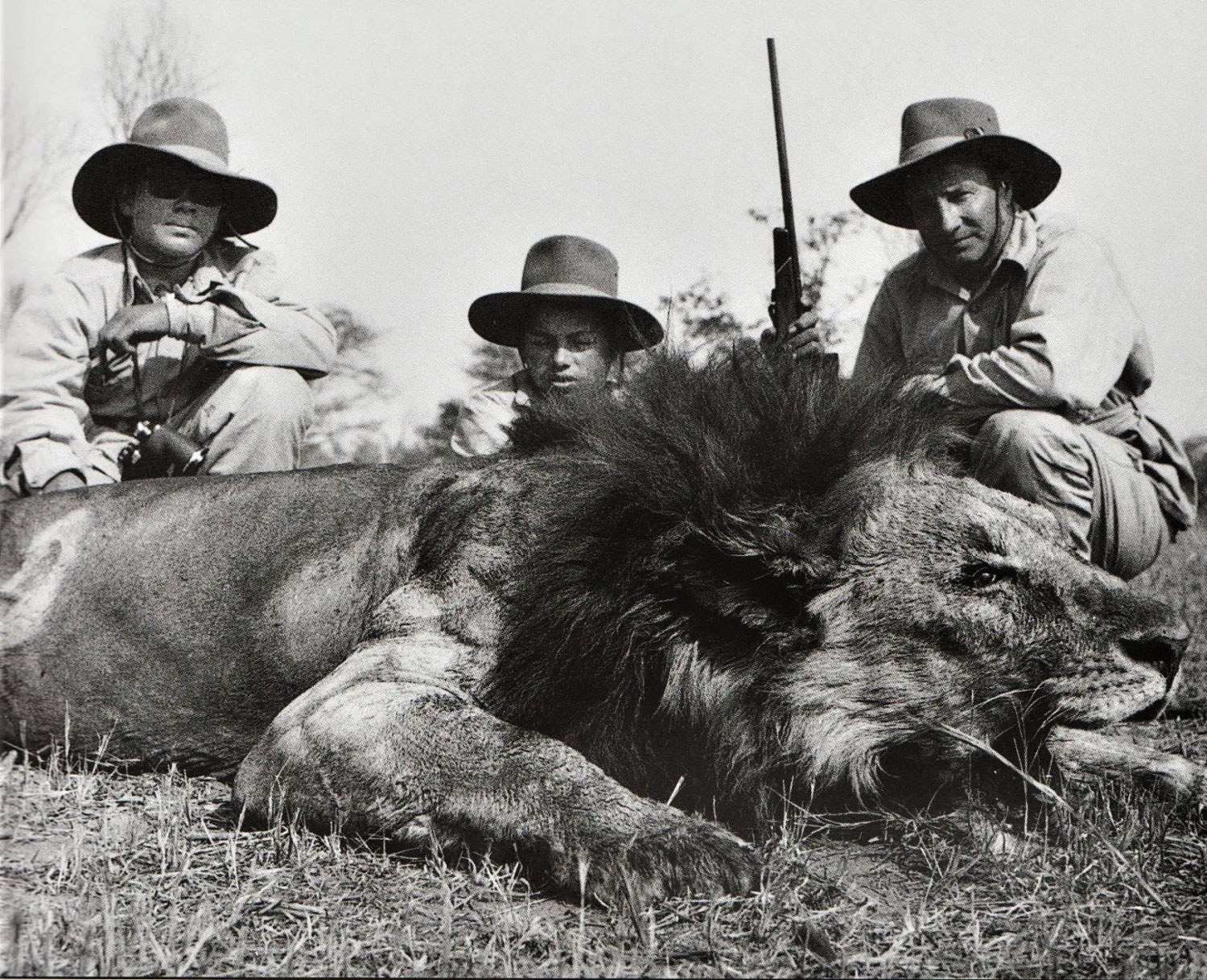

Elgin Gates poses here with his sons, Randy and Elgin with large maned lion killed in Bechuanaland. Photo: The Weatherby, Safari Press, 2004.

Numbers alone give him that status. Altogether he has more than 200 trophies listed in Rowland Ward’s Records of Big Game. Not surprisingly, most of those involve African game, because the Dark Continent was where he did the most hunting. However, there are more than four dozen entries for Asian game along with a couple dozen for North America. Look at it any way you wish, those numbers translate to a lot of time in the field and an obvious fixation with trophies. Indeed, during Gates’ life some critics sniped at his success, suggesting his preoccupation with trophies was over the top. There were even hints he stretched what was legal in terms of game limits and in other ways to acquire trophies, although there is no evidence proving such was the case. Jack O’Connor was not a Gates fan, but in fairness it should be noted that O’Connor was a stickler for purism in sport and perhaps at times a bit of a prude when it came to trophy hunting. As he once remarked on the subject, “As an international hunter and a collector of trophies I am small potatoes.”

Elgin Gates was anything but small potatoes. With an adventurous, inquiring mind, he led a life worthy of a Renaissance prince and exhibiting some of the versatility expected of such a person. Gates was evidently musically gifted, because the obituary notice for his wife Dollie Ruth Coon Gates, who outlived him some two decades, contains a delightful anecdote about how they met. He was playing in a band performing at Bright Angel Lodge at the Grand Canyon where she worked. Gates was instantly smitten when he saw her and, according to family accounts, proceeded to “destroy” the song being played. The couple married in Arizona, her native state, in 1941, but spent most of the years of raising children in southern California before moving to Ammon, Idaho, where both are buried, in the late 1970s. They had five children.

Musical talents and youthful pursuits behind him, Gates pursued a career in the marine engine industry, and one of his consuming interests throughout life, alongside hunting, was development of engines for speedboats and racing those boats. His achievements in that arena were impressive and, over the course of his career, he won multiple national championships and set a bevy of international speed records. He was among the founders of the noted California Colorado River Marathon boat race. Participation in boat racing required considerable financial outlay and his numerous hunting trips to Africa and Asia involved even greater expense.

Since there is nothing to indicate parental affluence, he was evidently sufficiently successful in his career to underwrite multiple pricey obsessions. His working career included opening and operating the Needles Trading Post in California for several years immediately following World War II. He and his family then moved to Seattle for a time before settling in Newport Beach, California. There he served as Mercury boat engine’s West Coast distributor.

Well to the forefront among Gates’ sporting interests was competitive shooting. He had won numerous target shooting competitions when a youngster, and that success carried into adulthood in impressive fashion. Gates won well over a dozen national or world championships in clay target shooting along with a trio of international competitions patterned after the Olympics. In the latter, he outshot the finest marksmen from the various branches of U. S. military service. He captained the U. S. team for the 1973 international competition. Never one to limit his horizons, whether they involved big game or competitive shooting, he became a master with handguns at a level matching his prowess with long guns. He was the founder and inaugural president of the International Handgun Metallic Silhouette Association (IHMSA) and a key figure in the sport’s development. In that connection he published and contributed regularly to a newsletter titled The Silhouette and continued as the president of IHMSA until his death.

An innovator as well as an energetic participant in the hobbies he pursued with such intensity, Gates collaborated with Dan Wesson in designing and testing all sorts of wildcat cartridge designs in the super magnum field. Some of his efforts, notably the 357 Remington Maximum, became production cartridges sold on retail markets.

For the better part of two decades, beginning soon after the conclusion of World War II, Gates took the long-running series of hunting trips abroad that form the focus of his modern-day renown. Along with Herb Klein and a few others he revived an interest in trophy hunting rivaling that of the great decades of big game hunting in the late Victorian and Edwardian eras. Gates was particularly important as a pioneer venturing into little hunted areas, and he purportedly had a standing agreement with noted PH Jack Blacklaws to fund exploratory safaris into virgin or long ignored hunting territory. One key stipulation was that Gates be part of any such adventure, with Blacklaws subsequently free to develop the area and entertain clientele as he saw fit. As a result, he reopened areas in numerous African countries where there had been little or no sport hunting for decades.

Not surprisingly, his feats as a hunter and shooter brought Gates all sorts of major awards. Having hunted on every continent, he received the Weatherby Big Game Trophy award in 1960. A few years later, when an international jury selected the six greatest living hunters, he was in their ranks, with his selection being heralded with a comment: “Elgin Gates is considered by many authorities to be the greatest hunter of them all.” He was inducted into the Big Game Hall of Fame in 1978 and a year before his death was recipient of what was often styled the Oscar of handgunning, the Outstanding Handgunner Award.

With their children grown, Gates hankered to return to the regions of his raising, and in 1965 sold his home, which included a 1,400-square-foot trophy room, to John Wayne. The famed actor turned it into a private theater. A portion of Gates’ massive collection of trophies ended up at the Omaha Museum of Natural History where it is known as The Gates Collection. There is a bit of murkiness, at least to this writer, when it comes to the overall fate of his many trophies. Multiple sources state that the collection was destroyed in a fire, but there is no doubt that a substantial number of mounts and memorabilia ended up in Omaha.

The persistent researcher can, through perusal of Rowland Ward record listings, view the end result of those safaris as well as other hunting forays by Gates in Asia and North America. But there is a far better way to get a feel for the nature of the man and his fixation with hunting. In addition to his many other stellar qualities, Gates was a first-rate writer. Some evidence of this is found in the numerous articles he contributed to magazines, but as is the fate of such transitory offerings, most are consigned to the dustbin of history or the dust-laden shelves of the periodicals section in a few libraries.

Such is not the case with his books. There are three of them and collectively they embrace much of the essence of his life as a hunter and shooter. Trophy Hunter in Asia (Winchester Press) first appeared in 1971 and Trophy Hunter in Africa (Amwell Press) in 1988. Both are somewhat difficult to find, not to mention being rather pricey, in the first edition. There were later reprints and you can find the Asian volume in first edition or reprinted form for less than $100. The African one, on the other hand, will likely require a layout of well north of $100. It might be noted that both books involved a noted name in the sporting books field, Jim Rikhoff. He was involved in public relations activities and book acquisitions for Winchester when Trophy Hunter in Asia appeared, while with Trophy Hunter in Africa he was the head of his own publishing venture. In his Foreword to Trophy Hunter in Africa, published in a limited, numbered and signed edition of 1,000 copies, Rikhoff promises a third work, Trophy Hunter in North America, to complete the hunting trilogy. It never appeared. The third book by Gates that did see the printed light of day is The Gun Digest Book of Metallic Silhouette Shooting (1979). Paperbound and mass produced, this volume is readily available on the out-of-print market for $10 or less.

To read his two “Hunter” books is to be transported to remote reaches and exotic scenes with the same sense of awe and grandeur afforded by the likes of Fred Selous or Sam Baker almost a century earlier, and therein lies, at least to the sporting bibliophile, Gates’ greatest legacy. For reasons not readily obvious to this student of the sporting past, he is surprisingly little known today. Perhaps his fixation with trophies or the relentless nature of his pursuit of them offers a partial explanation, but for anyone who enjoys remoteness of place, the thrill of the chase and armchair adventure aplenty, Gates makes a mighty fine guide.