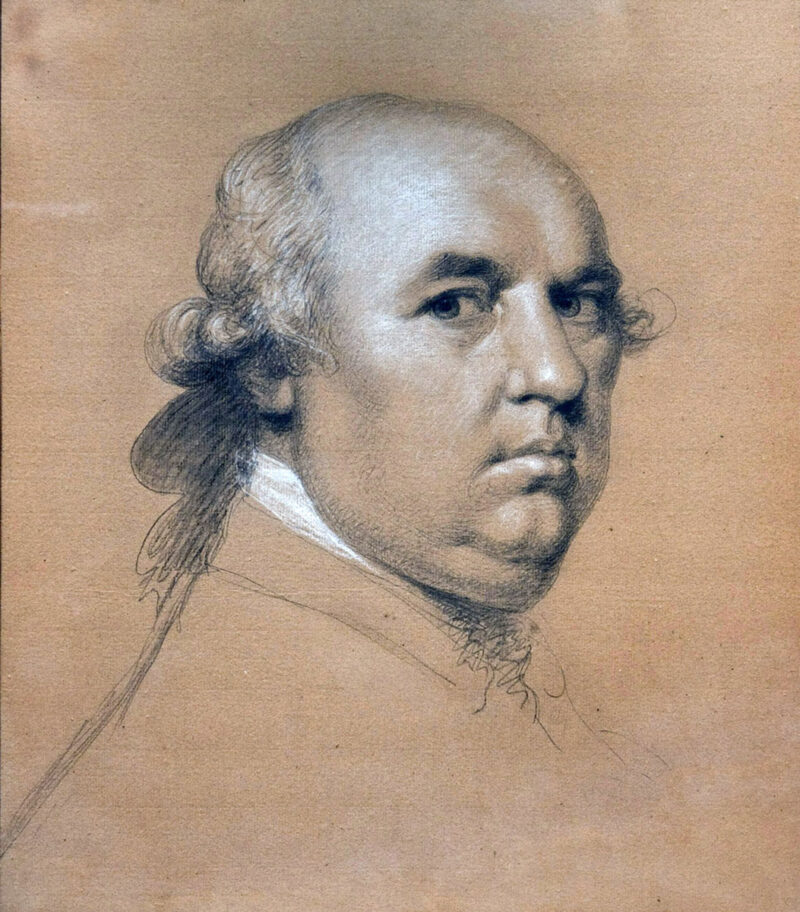

George Stubbs, 1777.

Stubbs’ mastery of the equine form was no accident. On the contrary, it was something he set out very purposefully to achieve. Born in 1724 and largely self-taught as an artist, in 1756 Stubbs—whose major accomplishment until then had been a set of “gynecological illustrations” for a book on midwifery—determined to re-invent himself as Britain’s foremost authority on the anatomy of the horse. And, by so doing, to create a profitable demand for his services among the various Dukes, Earls, Lords, Viscounts and Marquises who were eager to have the stars of their stables immortalized in oil.

Horse Attacked by a Lion, 1769, George Stubbs, enamel on copper.

Towards this end, with his common-law wife serving as his assistant, Stubbs embarked on a 16-month course of intensive anatomical study that has become gorily legendary in the annals of art. He essentially turned a barn into an abattoir: After killing a succession of horses by bleeding them out through the jugular vein, he injected them with warm tallow in order to preserve the integrity of their vascular systems. Then, suspending the carcasses from the roof beams via a block-and-tackle, he dissected them literally skin-to-skeleton, layer-by-layer, drawing in meticulous detail as he went. Each horse took six to seven weeks to work through—or, as Stubbs put it without apparent irony, “as long as they were fit for use.”

In any event, this “stinking business,” as one art historian described it, had exactly the outcome Stubbs hoped it would. His peerless understanding of equine anatomy, and of the myriad ways that that anatomy expresses itself and contributes to the more elusive quality known as character, brought him the fame and fortune he so fervently desired. And while it may have taken a while—200 years, give or take a decade or two—those months of obsessive study are ultimately the reason George Stubbs came to be recognized as the greatest painter of horses who ever lived.

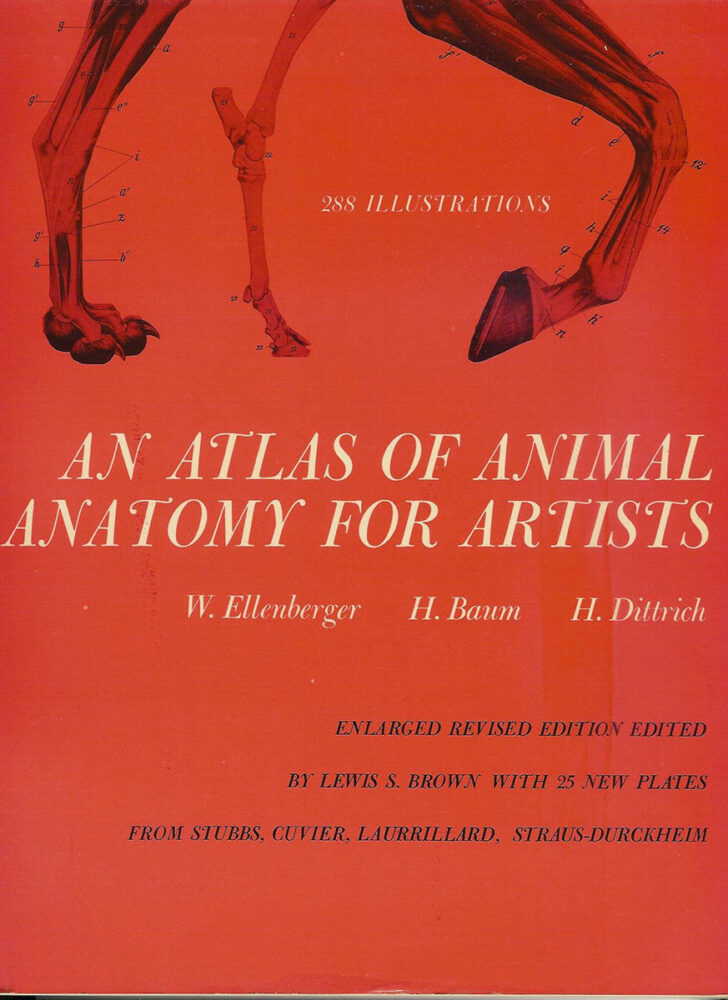

Every artist who attempts to portray animals in a serious vein, domestic animals in particular, has to contend in one way or another with Stubbs’ legacy. Mercifully, Eldridge Hardie didn’t have to go to Stubbs-like lengths when he set out to become a painter of dogs. Already a successful sporting artist, best-known at the time for his paintings of trout and fly-fishing, he decided in the mid-1980s to expand his horizons and add gundogs to his repertoire. After casting about for a bit, he found pretty much all the reference material he needed in a book called Atlas of Animal Anatomy for Artists.

Every artist who attempts to portray animals in a serious vein, domestic animals in particular, has to contend in one way or another with Stubbs’ legacy. Mercifully, Eldridge Hardie didn’t have to go to Stubbs-like lengths when he set out to become a painter of dogs. Already a successful sporting artist, best-known at the time for his paintings of trout and fly-fishing, he decided in the mid-1980s to expand his horizons and add gundogs to his repertoire. After casting about for a bit, he found pretty much all the reference material he needed in a book called Atlas of Animal Anatomy for Artists.

The dissection had been done for him, in other words.

But while Hardie’s journey of artistic self-improvement was perhaps less bloody than Stubbs’, it was hardly less obsessive—as I discovered when I visited him a couple of years ago at his home in the University Park section of Denver, where he and his lovely wife, Ann, have made their home for half-a-century. One morning, while we were driving downtown to visit the American Museum of Western Art (a must-see if you’re in the Denver area), I asked Hardie if he’d made a concerted effort to study canine anatomy.

“I sure did,” he replied. “When we get back to the studio I’ll show you the book on animal anatomy I used when I was learning to depict dogs.”

That afternoon, rummaging around in his heroically cluttered upstairs studio, Hardie produced the book. It’d been a while since he’d opened it, and when he did he found something unexpected tucked inside: dozens if not hundreds of pencil drawings that he’d done, literally from the skeletal level up, of the individual “pieces” of the dog’s anatomy. Shoulders, legs, ribs, muzzles, ears, tails—everything. Many of the drawings were accompanied by notes Hardie had written as reminders to himself of how best to represent the element pictorially.

“I’d kind of forgotten about these,” he admitted, pulling them out and spreading them across the table where he does most of his drawing and watercolor painting. (He does his oil painting on a conventional upright easel.) “They really helped me to understand how the muscles and bones fit and work, and that stood me in good stead later on.”

Echo’s Little Bit of Clown by Eldridge Hardie

Indeed. It’s a story I’ve related before (see Gundogs, S/O 2012), but around a decade ago Hardie accepted a commission from a Mississippi couple, Ed and Trudy Moody, to do a portrait of their National Champion German shorthaired pointer, Echo’s Little Bit of Clown, a.k.a., Bitty. The kicker was that Bitty had passed away, meaning that Hardie had to base his portrait on photographs provided by the Moodys as well as—and this is important—the memories they shared with him of her personality, achievements and exploits afield.

How well did his portrait fulfill their expectations? When Trudy Moody first laid eyes on it, she burst into tears. For someone who paints dogs, it’d be hard to imagine a more convincing testimonial.

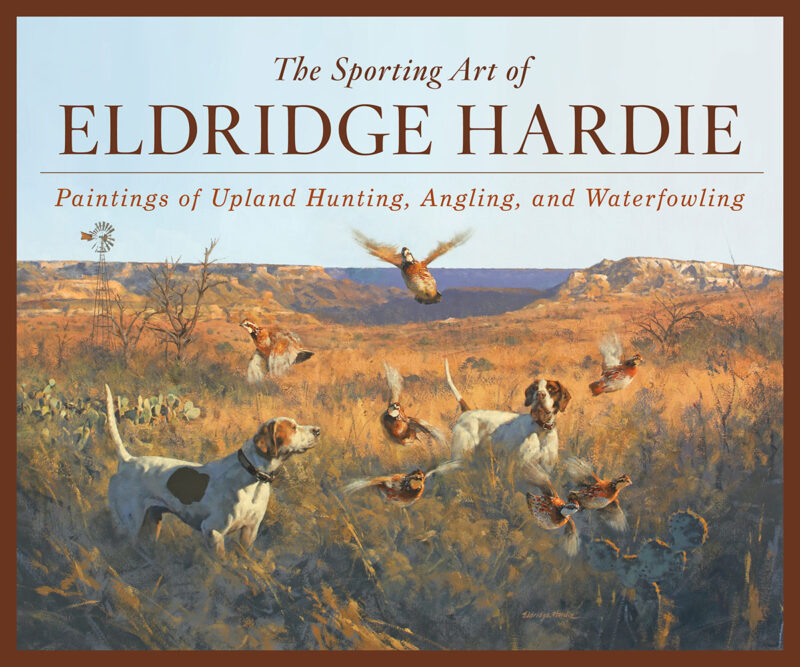

Panhandle Covey by Eldridge Hardie

Another ringing endorsement comes from the legendary M.F. “Bubba” Wood, founder of the famed Collectors Covey Gallery in Dallas (now closed, sadly) and a major influencer in the world of wildlife and sporting art long before “influencer” became a word. It’s a safe bet that no one has laid eyes on more paintings of Texas quail hunting than Bubba Wood—but he’ll tell anyone who asks that “Panhandle Covey,” which happens to be the cover image of The Sporting Art of Eldridge Hardie, is the best he’s ever seen. The brawny pointers in the foreground are classic Texas-tough bird dogs, the birds are so beautifully realized you can almost hear the rush of wings and the caprock country surrounding them is pure West Texas, in all its harsh, thorny, grandly desolate glory.

Some Open Water

“I’m essentially a landscape painter,” Hardie reflected one evening while sipping a martini (his specialty) in front of the fireplace. “But because I’m painting landscapes with a sporting narrative, the figures and the action have to be right. I enjoy that challenge, and the satisfaction that comes from knowing I have gotten it right.”

George Stubbs, that stickler for anatomical exactitude, would surely second that.

With a foreword by Paul Schullery and an introduction by Tom Davis, this book celebrates the artist’s six decades as one of the country’s best-known sporting artists. Considered by many as the world’s foremost sporting artist, Eldridge Hardie has been painting hunters and anglers on the water and in the field for more than three decades. Now, in his new large format, 12 x 10 inch book, The Sporting Art of Eldridge Hardie, the gifted artist presents 150 paintings of upland bird hunters, waterfowlers and anglers. Readers will love his detailed depictions of many different breeds of gundogs. Throughout the book are sidebars relating to the general subjects of the paintings gleaned primarily from a lifetime of the artist’s own hunting and fishing experiences. There is also a special section devoted to the creative process where original paintings are paired with the preliminary studies and notes leading to the finished pieces. Buy Now

With a foreword by Paul Schullery and an introduction by Tom Davis, this book celebrates the artist’s six decades as one of the country’s best-known sporting artists. Considered by many as the world’s foremost sporting artist, Eldridge Hardie has been painting hunters and anglers on the water and in the field for more than three decades. Now, in his new large format, 12 x 10 inch book, The Sporting Art of Eldridge Hardie, the gifted artist presents 150 paintings of upland bird hunters, waterfowlers and anglers. Readers will love his detailed depictions of many different breeds of gundogs. Throughout the book are sidebars relating to the general subjects of the paintings gleaned primarily from a lifetime of the artist’s own hunting and fishing experiences. There is also a special section devoted to the creative process where original paintings are paired with the preliminary studies and notes leading to the finished pieces. Buy Now