The Lowcountry panther entered my dreams and my life. Haunting me when I slept, quickening my pulse and step when I was alone in the swamps come sundown.

Daytimes, the Old Man looked off into middle distance. Nights, he gazed deep into campfire flames. He held us captive with the motions of his hands, the rise and fall of his voice, the rhythm of his words, the pauses in between his words. The Smithsonian sent two Yankee women to get him on tape, reel to reel in those days.

“On Roseland Plantation back when I was a boy, the panthers squalled like women way down in the swamp.” He paused and looked me square in the eye, “Boy, you ever heard a woman squall?”

Well, I heard Momma crank up a time or two. She wept and wrung her hands and got so mad once, she fainted dead away, but she never squalled.

“No sir,” I said.

“My grandfather had to keep the hands up all night feeding bonfires around the barnyard. When a panther hollered, the meanest coonhounds rolled their eyes, backed up to the fire till their tails smoked and stank.”

I saw it all in my mind, the colors of the hounds, the white of their eyes and I smelled their burning hair. Thus the Lowcountry panther entered my dreams and my life. Haunting me when I slept, quickening my pulse and step when I was alone in the swamps come sundown.

The Lowcountry of South Carolina, from the swamp of the Great Santee to the swamp of the Great Savannah, 200 miles. Something gonna slip through the cracks, it could slip through here. A half-billion dollars worth of reefer did and I know the boys who slipped it. But that’s a whole nuther story.

Panther, painter, catamount, puma, wampus cat, mountain lion, Puma concolor – it’s the most widely distributed land mammal in the New World, from Patagonia to the wilds of the Yukon. A foot longer than a man is tall, a big tom will tip 200 pounds. Paws big as Waffle House waffles, fangs you don’t want to fool with. Call it the Ghost Cat too. What in the world did I just see? They appear and disappear like swamp-ground haints. They have been in South Carolina since the successful conclusion of the last Ice Age, but no longer. And why not? Because the US Fish and Wildlife Service says so.

On March 2, 2011, after five years of review, the Service declared the eastern cougar extinct since the 1930s. “While we realize that many people have seen cougars in the wild within the historic range of the eastern cougar,” said Mark Miller, northeast chief of endangered species, “we believe these were not the eastern subspecies. We find no evidence of the existence of the eastern cougar.”

Mark Miller needs to get himself down here and tip brown liquor with Tommy Baysden. Baysden worked with conservation developers for 30 years, capping a stellar career as vice president of Palmetto Bluff in Beaufort County.

“In 1978 I saw one, with a young one, on a ricefield dike,” Baysden says. “Two witnesses were with me, David Maybank and Drayton Hastie of Charleston. We looked at each other, our mouths hanging open, and said, ‘Can You Believe What We Are Seeing?’”

Lee Gray would have no problem believing. He saw one two years later, off the New River on Palmetto Bluff. A big black tom, he says, with a scrotum like a sack of oranges, crossing a deadfall pine across a rice canal. “I was fishing with my grandson, but he was too young to remember. I got a good look at him,” Gray wryly recalls, “so there was no need to get out of the boat to investigate further.”

Up on the Palmetto Bluff high ground, Patty Kennedy was director of the local conservancy. “There were ten reported sightings in 2008,” she remembers, “most said the panthers were black but given dim light and a generous plastering of mud, they could have been just about any color at all. We set up game cameras. We got lots of deer and bobcats, but no panthers.”

Not so far away, Howard Hart was making a late-night run to pick up a load of crabs for Golden Harbor Seafood in Yemassee when a panther crossed the road in front of his truck. “She was skinny and emaciated, almost like she had mange,” Howard remembers. “I called my boss Charlie Marshall and he allowed I had been drinking too much beer. But he made the run the next night and he saw her too, this time with a long string of spotted cubs in tow.”

Jamie Floyd of Walterboro is a believer, too. He captured the unmistakable image of a panther on a game camera in 2000. Though the photo has since been lost, his buddy Bubba Erwin of Whitehall saw the photo and will vouch for it.

Ten years later and 10 miles away, Bill Hameza, got within a couple hundred yards of two tawny long-tailed cats while heading for his deer stand in Colleton County in November 2011. Juveniles, he reckons, about 100 pounds each. Hameza would not get out of his truck. “I hesitate to talk about it,” he says. “People might think I’m nuts.”

Drunk or crazy, common reactions from skeptics, official or otherwise. But what if the report comes from a cop, a trained observer whose word is accepted prima facie by any court in the land? What if he is a very special cop, good enough to work undercover?

About 10 years ago, an undercover enforcement officer saw one cross the road not 20 yards behind his truck near Green Pond. There was not enough evidence for indictment, only indistinct pugmarks in sugar sand. His report was dismissed by his own department’s biologists. “I’m no veterinarian,” the unnamed officer said, “but I know what a horse’s ass smells like. And I know what I saw.”

But Ben Moise, retired warden with 27 years in the marsh and mud of the wild Santee, remains skeptical. “I used to get reports all the time, usually of black panthers. I kept a gallon jug of water, a sack of plaster of Paris and a mixing pot in the trunk of my patrol car. When I got a report, I asked the caller to cover the tracks with a bucket or trash can. I went to every sighting for years and took casts confirming only the passage of dogs, otters and a few bobcats.

“One man even testified he saw one up on an overhanging limb gnawing on the carcass of a deer the beast had carried up into the tree,” Moise adds. “Another person swore one jumped on the hood of his car and stared at him through the windshield! I continue to hear reports of sightings from ostensibly knowledgeable people. But in all my years in the wild, I neither saw one or heard one.”

So what we got here? A pineywoods Twilight Zone? Some stump-jumping collective madness? A feline Big Foot?

“We’re talking folklore and sociology now,” says Billy Dukes, DNR staff biologist. “People will believe what they want to believe. But the fact remains we have had no credible evidence of a free-roaming, self-sustaining population of panthers in South Carolina since about 1940.”

Retired DNR biologist Sally Murphy amplifies the official explanation: “There are many cougars in the exotic pet trade. When they get too big, people just turn them loose, usually in a remote, wild place. Some of them might be able to survive in the wild, given all the deer we have now.”

Charles Ruth, now the senior deer and turkey man with the DNR, got sent after panthers back in 1990. “Don’t get yourself killed,” his boss advised. One panther had a collar, the other a tattoo. Case closed?

On June 11, 2011, a scant four months after the Feds held their last rites for the eastern panther, a panther was killed on the Wilbur Cross Parkway just outside Greenwich, Connecticut. DNA had the final word. The beast was from the Black Hills of South Dakota, some 1,600 miles away.

Though New England has its share of reports and rumors, there had not been a panther positively documented in those parts since 1938. The New York Times ran an op-ed piece by Public Radio’s David Baron, “The Cougar Behind Your Trash Can.” Baron noted to a rapt readership, “The Greenwich cat may have been a lone scout, but you can be sure others will follow. The resilient, elusive cat that haunts the Western landscape will increasingly haunt the East . . . . America has grown a bit less tame.”

Scientists have been pawing over Puma concolor since 1792, classifying and reclassifying until there were some 32 separate subspecies, all done without benefit of DNA. In 2001 researchers Culver and Johnson gathered DNA samples from hundreds of cougars, alive and dead, released a landmark study, The Genomic Ancestry of the American Puma.

Culver and Johnson noted while there were significant genetic differences among various isolated South American populations, there were none among their North American cousins. They then shocked and outraged the scientific community by insinuating there never was an eastern panther, just panthers in the East!

And what about the endangered Florida panther, generally known as Puma concolor coryi, down to 20 dispirited and inbred individuals in 1995? After the introduction of eight females trapped in Texas, the population now stands at about 160 adult individuals. Are the Florida panthers truly unique, or are they just panthers isolated in Southwest Florida? Don’t matter now, the Florida panther is now the Texas panther as it likely was before I-10 and I-75 got in the way. But Billy Dukes cuts right to the chase. “I don’t care about the DNA helix. If there are still big cats in South Carolina, show me one.”

I tried, canvassing the internet, haunting backcountry bars, gunshops and feed stores. If these folks hadn’t seen a panther themselves, they invariably knew somebody who had. But proof? Closest I got was digital scan of a blurry print, an image captured on a game camera back in 2007. Panther head, panther ears, long, strong, low to the ground, a splash of white around the maw, perfect. But damnit-all, there was no clear view of the tail. I slapped it up on Facebook and got 44 comments in two hours.

“Before this is over,” Ben Moise cautions, “you’ll have a bonafide photo of Elvis riding on the back of an eastern cougar in hot pursuit of the Lizard Man.”

Billy Dukes would like that.

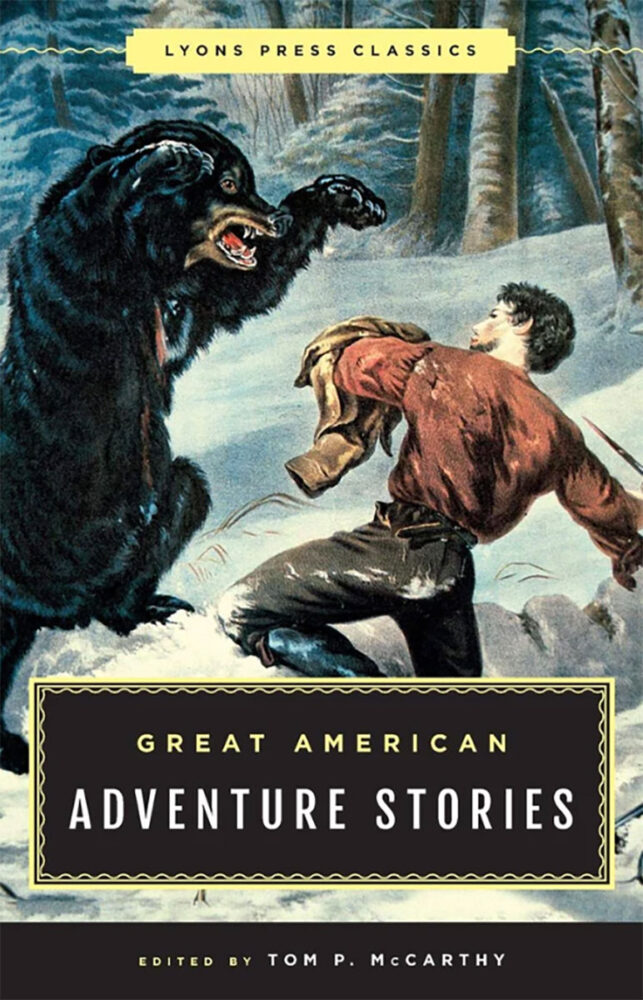

Great American Adventure Stories contains page-turning accounts of the Galveston Hurricane, the Alaska Gold Rush, a robbery featuring Jesse James, an eyewitness account of the Johnstown flood, and much more. For a taste of the American frontier, Daniel Boone and famed scout Kit Carson depict what they saw and experienced as the country expanded and blossomed in the West. These accounts all have one thing in common: They capture the grit and spirit of people who made America what it is today. Buy Now

Great American Adventure Stories contains page-turning accounts of the Galveston Hurricane, the Alaska Gold Rush, a robbery featuring Jesse James, an eyewitness account of the Johnstown flood, and much more. For a taste of the American frontier, Daniel Boone and famed scout Kit Carson depict what they saw and experienced as the country expanded and blossomed in the West. These accounts all have one thing in common: They capture the grit and spirit of people who made America what it is today. Buy Now