This story is true, as true as you wish it to be…as true as the truth of all the great grouse dogs and all the great grouse men and all the great wisdom birds that ever lived. Who now are gone, but not forgotten.

It arose as a distinctive and low-lying hill along the Great Allegheny Plateau, north of the Susquehanna Valley, and not greatly distant from the western reaches of the Endless Mountains.

Its signature was its singularity, from either north or south appearing the same, squared of base and shouldering abruptly on its eastern and western rise, before narrowing progressively and prominently to a peak. Thereby attaining the semblance of church and spire, it had been known, for as long as history could remember, as Tabernacle Mountain. An enduring inspiration to the hardy pioneering families that braved hearth-and-hardscrabble through the early years to settle these old hills and hollows in the once Eastern wilds, a veneration which had persisted through the many generations, until even today it was held greatly sacred among their descendants.

A temple of exultation in the greening of spring, and an allegory of faith through the drab, gray-white siege of winter, it was ancient as the mother range itself, 480 million years along, the oldest and most time-worn mountain chain in the world: the primal Appalachians.

Standing wild, rugged and withdrawn, it had reigned through the eons both a fortress of retreat and haven of survival for the strongest and hardiest of God’s creatures, from the bear to the bobcat, from the eagle to the sparrow.

Largely escaping by its foreboding inaccessibility and locally revered spiritual presence the great carnage of 19th century lumbering exploitation, it was yet thickly forested by great stands of vintage timber—black and yellow birch, oak, white pine, white ash, black cherry, striving sprouts and saplings of once-kingly chestnut and towering, 700-year-old monolithic centurions of hemlock.

Though broken intermittently as well by a bountiful patchwork of new growth in various and early stages of succession, creating beneath the fire-blackened skeletons of standing dead timber small meadows of lush undergrowth. Seedlings, saplings, shrub and brush in thickened profusion: among them aspen, witch hazel, cherry, birch, greenbrier, ironwood, dogwood, filbert, fern and salad greens, tender green leaves, and flowering, nut and fruit-bearing orchards of hazel, thornapple, wild blueberry, blackberry and elderberry…even rare and prodigious drupes of bush cranberry.

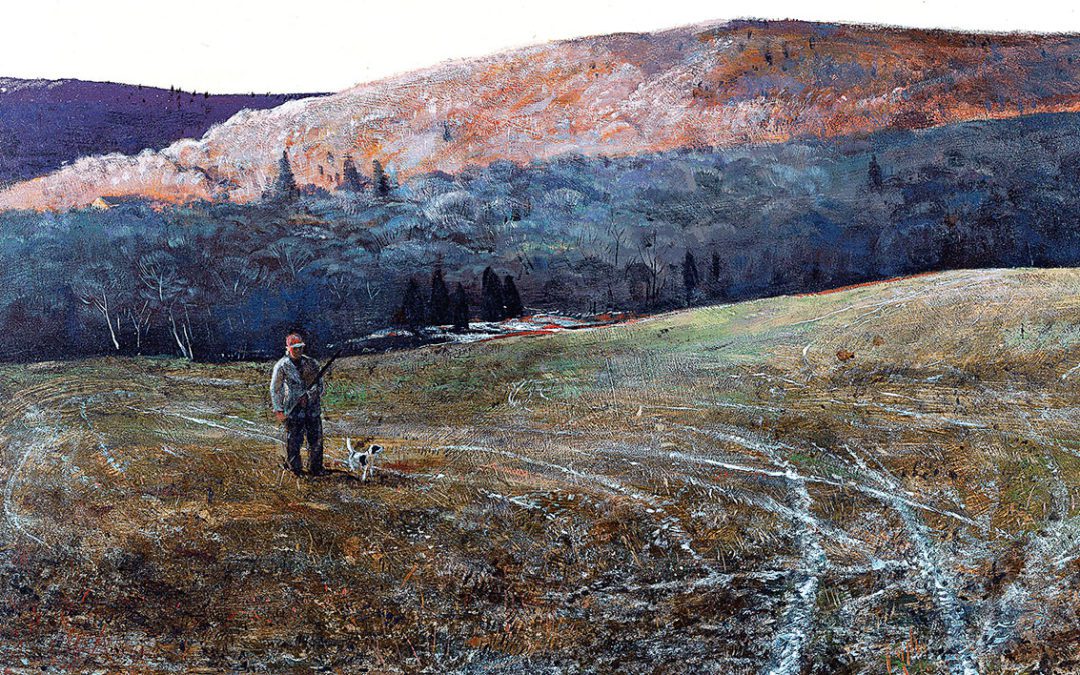

The Edge of Memory by Rod Crossman

Rich also in bugs and insects in spring and summer, it gave birth in all seasons to a cornucopia of rich and sustaining buds, flowers, nuts, fruits and greens for the myriad things wild and untamed that made it their home. For which it was often called also, the “Mother Mountain.”

But it was not Valhalla, not altogether a cathedral of peace. For beneath its benevolent countenance, it was home as well to the multitudinous battles for existence that raged day-to-day among the very creatures it sheltered. Mouse and shrew, rabbit and hawk, owl and partridge. Blood was shed hourly in the monumental, violent and relentless contest between predator and prey. It had always been that way, and so it would always be, in the capricious and largely unwitnessed conflict of everyday life-and-death.

And, now, upon this theater and venerable mountain would unfold another battle, more epic than any before, between combatants cast coincidentally but mortally into adversarial blood sport that would demand equally of them their every instinct and wile. With which both were super-naturally endowed. Until, eventually, one would give to the other the slightest advantage that will be the precursor of his doom.

But they were destined to meet, and one would likely die, and the other continue, without remorse, to live. As that was the order of wildness, the order of the world in which their fortune was cast, void of sentiment and replete with only the fury of the quest and the struggle for survival.

The cunning and tenacity of their encounter—for each within the span of his lifetime—would become legendary. At its beginning, only within the boundaries and across the distance of one man’s heart. Until it evolved so spectacularly that he found he could no longer contain it, that he must share it, but then only within the sage circle of men whom he thought had earned the wisdom to understand.

Though he would never reveal the exact geography of it, only the greater tableau of the mountains. This they knew and respected too, for between them such discretion was an inviolable mantra of honor—though many presumed correctly that it did not fall far from the one, sacred mountain.

They listened astutely, and nodded understanding. And it passed first from one and then to another, so that the legend grew both far and wide. Eventually deriving to full disclosure.

Persisting today, never to be forgotten and ever to reign supreme. As long as dog men live and breathe.

This is the climactic episode of their story: the story of a gray partridge and a tri-colored setter. Cast against each other on a grouse-sacred mountain. Each super-naturally gifted within his time. Each with the all-consuming mission in life they were born for: to best the other.

For three years the duel between them raged, and fell largely to a draw. In the process, they re-wrote every standard of excellence in the Cover-Bird Bible.

The days and the seasons and the battles ran by so painfully fast that nobody could stop them. And Lord be, the Old Man wanted too. For each, it seemed, was more magnificent than the last, and so sadly he knew that as surely as they passed, they could never be again. Yet, every one was perfect, and he had at the same time never lived so happily or completely. With his son by his side, and at the grand center of it all, the tri-setter and the gray partridge, gifting the thing he loved most, the greatest blessing of his lifetime.

But perfection has no shelf life, and too soon must bend. Want or not, every season must end.

On January 30, 1987, the final clash between the old gray partridge and the tri-setter came to stage, on the western slope of the mountain. It was the last time they would ever meet, and on that day the outcome would be, for once and only once, wholly decisive. One would win, and one would lose, so convincingly—in that they had always been so superbly matched—that this alone defied belief.

One would lose, and one would win. Yet both would triumph. One by wit, and one by grace.

It unfolded that day as nearly it had almost a year to the day before. The gray partridge had fed in the apple orchard at the old home place that morning, on the dormant buds of the bent and tortured old trees. That stood stooped and wrinkled like old women with shrunken, pendulant breasts and withered loins, except that in the coming of spring they still gave birth. Bore again the fruit of their genes. But now it was winter, and they were humped and barren and cold, over a ground-cover of fresh snow.

The January sky was heavily clouded, low and thick, smooth and gray, the color of sodden ash. Beneath it, the air was breathless and silent, whisper-still. The woods were hushed and huddled, as quiet as the fallen snow, so that when deer walked, they chose each step with great care, stealing along as noiselessly as their surroundings. The small birds among the shrubs spoke softly and sparsely. The band of crows that lugged lazily by, said nothing.

There was about the sacred hill, a reverence. As if all had been touched by the hand of God, and lay yet in the awe of his passing. As if someone long past had wishfully lit a candle in the veritable spire of the great mountain itself.

It did not escape the senses of the Old Man, in the moments before he and his son released the anxious setter, shortly after noon, at the lapse of the wagon road east of and a thousand feet below the old hemlock log. He stood looking for several moments across the ridges, to the gray horizon. While his son stood to the side, watching and knowing. And the old man understood then the more, that somehow, this would be the last. That on this day, and upon this somber and consecrated stage, the curtain would fall, the cast would take its last bow, and the play that had spun so joyfully for three incomparable years would lapse to close.

He had rather it not, and would have saved it should he could. To keep unspent, to hold and savor —to cherish for the remainder of his days—like a silken and beloved lock of hair removed upon occasion from the other treasures in a small wooden box. Even though, if he did, he would never know the way the story would end.

Then he had dropped his eyes to the dog, the setter up on his toes, flagging briskly, burning to go, like fire blazes when it’s fanned by the wind.

But then there was the dog, the Old Man thought to himself, for whom there was only today and no preclusion of tomorrow. To whom he owed it all.

And he stooped, stroked the tri-setter’s sides briefly, the hard and muscular flanks of the greatest grouse dog he had ever known, and with quaking fingers undid the snap from his collar.

“Find him,” the Old Man said, so softly only the dog could hear.

The setter broke, bunching and lunging powerfully up the mountain like he had wings. Locked in a beeline for the great hemlock log. Once again, in another season, he had one encompassing mission, into which he would pour heart, sinew and soul. And only one.

In short minutes he had reached the massive throne of the drumming log, fanning the surrounding cover, flaming with hunt, opening a ground-blistering, widening search for its sovereign.

Dawn Drummer by Brian Jarvi

Below and behind, the Old Man and his son lurched with equal enthusiasm into their attempt to maintain contact with the dog. It was agreed. If the engagement, once joined, carried far ahead, the younger man would go alone. Cover the find if he could, if the bird ever held . . . delaying the flush if at all possible until his father could get up.

The Old Man had put the worn old bell on the setter today, so they could better hear its deep and melodic tone. It was the one he wanted to hear, the one all the dogs of all his days had worn: Penny, Jesse, Jase, Talon, Drummer, Mack, Jacob, Luke and John. It did not matter as much as in the beginning. The battle would be enjoined if the gray partridge was still there. He would have no choice, regardless. That was a certainty. The setter would hardly be handicapped by the larger bell.

“Clang-da-ding-ding,clank-a-ding-ring.”

He could hear, even with his tired old ears, the scorching ascent of the dog up the mountain. “God-a-Mighty. Had there ever been—would there ever be—sweeter music?”

The setter, finding nothing immediate, widened his hunt, throwing himself into it with pent-up fury. Faster and faster, bolder and bolder, broader and broader. The bell was singing a torch song.

On the tri-setter flew, zig-zagging across the slopes, to check the next likeliest spot, then the next and the next—where he had found the old bird before, and never forgot—until soon he neared the old homeplace. Heading for it as irresistibly as if he were an iron filing under the spell of a magnet. It was here he had found the gray partridge a half-dozen times before, and it was here—for the last time—that he would find him once again.

The setter was flying, incensed and consumed by unrequited desire. The electrifying, ever-familiar scent of the gray bird hit the rushing dog mid-stride, so close and hot it was galvanic. The setter jammed the brakes so hard that in return his back feet left the ground, and when he settled he was locked twelve-high and six-low, his chin almost touching the earth, his flag stiffly over his back. Jacked sideways as a hair-pin, and afraid to breathe.

It would have been a heart-stopping thing to see, absolutely breathtaking. The style and grace of the dog bent so suddenly and torturously, but ever so beautifully in homage to his goal. The suspense of static motion cocked and instantly ready to explode, the anticipation—again, after so long—of flight—the any-second, booming and unnerving explosion of the arrested gray bird…all shimmering in dancing white heat waves over the bold setter’s stand.

Both men had heard the sudden lapse of the bell, the younger rushing, stumbling through the cover now, to get there. It would never happen.

When the old gray bird had heard the deep-throated clang of the bell, he knew instantly his dilemma. That he was bound for peril, that the setter, as ever before, was relentless and virtually unshakable. He had no choice. Sooner than later he would be discovered, no matter what he did. It was a thing of what he should do first. Something that would possibly throw the dog off-guard, give him a chance to employ a secondary strategy in the moments the setter might pass him by. At least on his first pass through the orchard.

What the old bird did was purely and virginally a matter of instant and instinct. Still in the tops of the apple tree, air-washed by the westerly breeze, he cupped his wings, dropped, and settled himself into the thick gather of saplings and briers at the very base of the tree. Did not further move. If he could or would ever have the capacity to “hold” his scent, he must practice it now. When the dog was safely by and a ways away, he would move again, this time in a much more convoluted means off the knoll.

But the tri-setter, instinctively as well, was too smart for that. He had learned now—long since—to read the wind, to stay ever downwind of the most promising cover, and the path of his first cast through the old orchard took him precisely east and only five feet below where the gray partridge was hiding.

When, taken off-guard himself, the old bird found he was immediately discovered, his fright spiked and his sudden surprise—fanned to panic by the instantaneous halt of the dog—was more than he could stand. Up he exploded, in a thunderous roar, almost in the after-instant the setter slammed to point. Spinning off and away into a sharp oblique, flying low and gathering speed, then setting sail three hundred yards down the western slope of the mountain.

The tri-setter swelled, otherwise immobile, listening as if his life depended on it. Then he burst away, in hard pursuit of his fleeing adversary.

The two men below, the younger almost there, stopped simultaneously. Listening together to the once again animate, equally disappointing and thrilling peal of the bell.

The battle was enjoined. It had to be the gray partridge. This was his territory and this was his way. And now, though both men were war-wise and inured to the many utterly amazing clashes of the past—between an incredibly brilliant dog and an unbelievably-resilient bird—they would find themselves unprepared to conceive, or later come to believe—what was about to unfold so astonishingly in the closing match of their crusade.

It was a championship game of chess, between champions, and today, both players would be superb.

When the gray partridge settled, 300 yards down the mountain, it was not to the ground, but to the tops of the laurel. And that’s where he stayed, unmoving, perched and waiting. The setter was soon on the scene, working the eastern edge of the thicket, reading the incoming breeze. Scenting conditions were perfect, and the westerly breeze brought the dog the advantage of the slope, placing the easterly-drifting spoor of his quarry practically at the same elevation he hunted. Which the gray bird had not configured. So that while the tri-setter could not precisely locate its source, his uplifted nose nevertheless and unerringly captured the faint, incoming tendril of scent and stopped it cold.

Immediately, the setter broke into a quartering frenzy, seeking to better his advantage. Dashing into and cutting tight “Ss” through the laurel, weaving himself more intricately into the spoor, which was strengthening. Only to twice lose it strangely, before reversing and regaining it. It was only moments later before he was almost directly under the gray bird, drinking in the suddenly hot scent filtering in a telltale shower from the leaves and limbs above. Instantly, he whirled and snapped to point.

The ruse was up and the gray bird knew it. Going out low, skimming the tops of the thicket, he set sail again, his straight, then left and finally right counter-movement taking him further down the mountain.

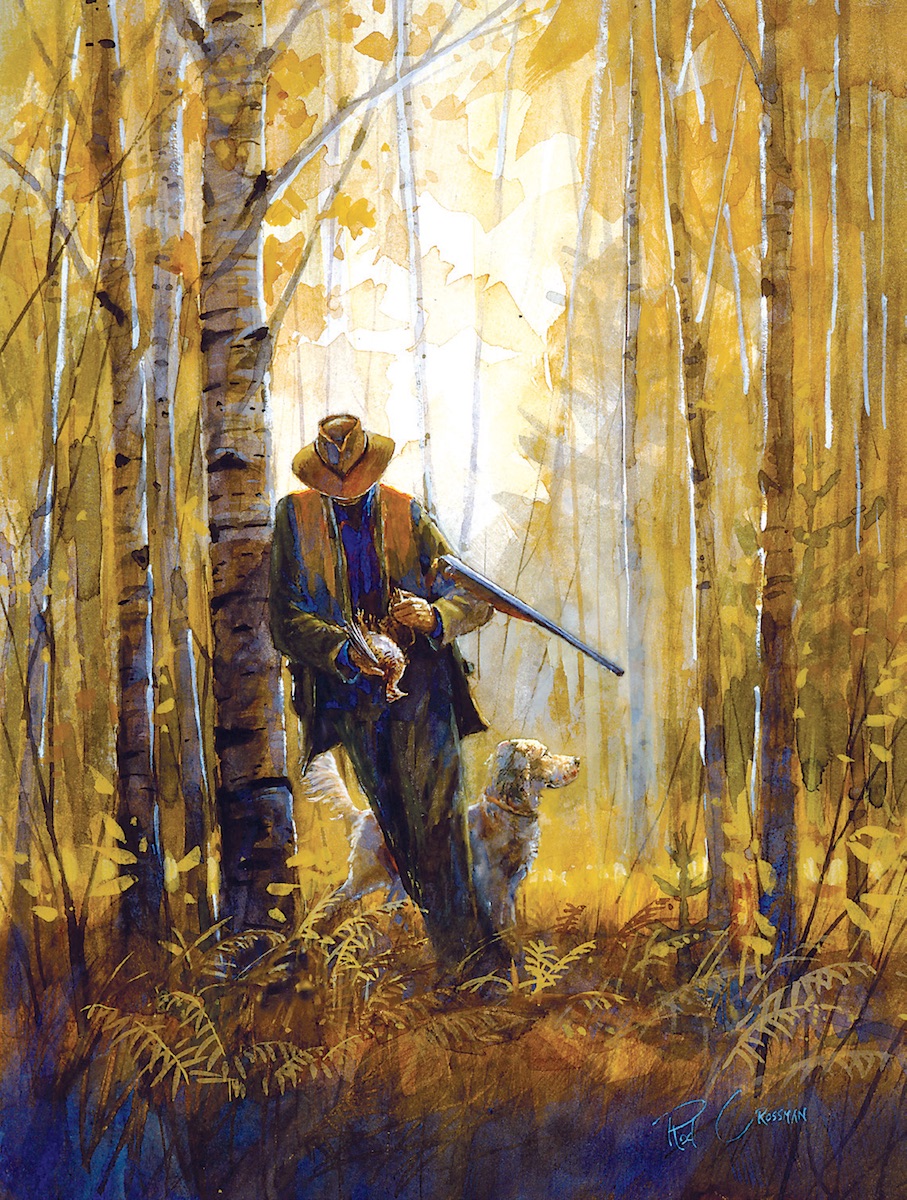

Frosted Apples by Chet Reneson

The setter read the sound of the bird’s departure. Did not follow him directly, but veered north, drifting right and racing 300 yards more down the mountain.

His judgment was infallible. Once more, no less than incredible. It took him scant minutes to find where the gray partridge had reached the ground, and quickly he was engaged in the furious attempt to find him.

He was so inebriated with the chase, he ran by the old bird twice. For the gray partridge knew his dominion to the leaf, log and feather, and the trail had mysteriously disappeared after a mere 30 yards. The setter wove widening circles, then closed again, frantically trying to recover it.

A foot under the snow reposed an old, hollow log, some twenty feet long, and open either end. The gray bird had used it once before, and now he squeezed himself deeply within its recesses, hoping to be as successful again. It was a bold gamble and he knew it. If he was trapped there, all would be over. But he was playing a card he had not used before, one of the slickest tricks in his deck, and he wagered it would work.

The setter tore up and down, around and around—back and over the hidden bird again and again—trying desperately to pick up warm scent, but to no avail. He hunted in utter frenzy now, burning with frustration and desire to reconnect the war. Scouring the vicinity until his tracks completely crisscrossed and rumpled the pristine cover of the snow. While below in the dark recess of the log, the gray partridge could hear above the dog’s bluster, but this time lay still and did not move.

It might have worked. For the first time since his advanced puppyhood, the tri-setter might have lost there and then. But his instincts were too good, and he would never break off or quit. After ten minutes of futile searching, he reverted to the basic ploys of wildness. Becoming no longer the statuesque paragon of style and splendor he struck when he winded the gray partridge on fair turf, but the make of his brothers: the fox or the wolf.

Returning to the spot of last scent, which now lay cold, he buried his muzzle in the snow, snuffling and blowing, and sorting the scent. Which immediately became mildly stronger. Now with a fury, he dug with abandon, snuffling, inhaling and testing the newly exposed and frozen air, blowing the snow from his nostrils and testing again.

The deeper he dug, the warmer the scent, and suddenly as he dug the last inches of snow away and exposed the open end of the covered log, the hot spoor of the gray bird was sucked into the vacuum of his nostrils, and he knew he had found home. He ran his muzzle as far as he could into the empty, black hole of the log, drinking in the inebriating, hot scent of the hidden bird like a week-long, itinerant drunk taking his first swallow—wallowing side to side in the snow, whining maniacally with frenzied aggravation and raking at the log with all his might. Doing all within his power to reach the bird.

Inside the gray bird knew yet again that he had been found. Moving further from the end of the log the dog was attacking, he still did not go, but stopped and squatted, considering his options.

It was then that the younger man arrived, reading the scene—the trampled snow, the frenzied labor of the setter—in short order. He spoke to the dog, acknowledging his predicament, and taking stock of what he could do about it. The log was of only moderate size, and he thought immediately that he might move it. At least lift and drop it, to shake loose the bird that had to be hidden inside. But he could not do it with the gun in hand.

Laying his gun in the snow, the man bent—despite the setter still tearing at the mouth of the log—ran his hands under opposite sides of its trunk, bent his knees and heaved with all his might. The first ten feet of the blackened log was freed from the snow, lifted airborne, then violently re-deposited with a jarring thud to its resting place.

The gray bird would stand no more. Out the off end of the log he blew, as the power of his wings opened the way through an explosion of snow into the somber gray sky. Immediately, the surprised setter planted himself, marking flight, as the man grabbed wildly for his gun.

What the gray partridge did next was totally unpredictable. And that was why he was the gray partridge. It could perhaps with difficulty be attributed to reason, but was more likely the conclusion of instinct forced to the wall in a desperate season. Not unlike the setter, whose fundamental faculties had drawn him to the hidden log when all else was lost. Say what you will, and many folks did, both ways . . . but the one sure thing, all would agree, was that it was intended to bewilder and disarm his attackers.

Rather than leaving ground-high and straightaway, peeling low and away right or left as the Old Man’s son rightfully expected, the old bird threw caution to the wind, rolling, looping, spinning and speeding in a direct, level path toward the man’s face. The hurling bird came so fast, so hard, that it happened in sheer seconds, surprising and startling the man so that he instinctively ducked, slipped and stuttered on the slick, frozen surface of the snow. As the dog whirled, planted, watched the hurtling bird away. To disappear just as the man brought the gun to shoulder, once again, too late. As the standing dog broke, scratched off, and tore away.

The young man stood shaken and chagrined. With totally new respect for the gray bird. They had had him—the old gray rascal—dead-to-rights, right here under them, and still he managed a getaway.

His father finally was up, then, and as his son related the incredible truth of what had happened, the Old Man grinned. Shook his head, then chuckled out loud. Just as he had never before known a dog so good, he had never known a bird so shrewd.

Farther down the western slope the old bird sailed. Two hundred more yards, then three, hooking left and beating for another 50 before he dropped into a dense clot of aspen, breaking to dense young rose clusters, then alder, willow and fern. But he had little more than lit when he could hear once again the oncoming rush and clang of the setter’s bell. For the next 20 minutes he would rely on his running game, leading the setter into tighter and tighter cover, threading and weaving all the while, as behind him still the damp and friendly, westerly breeze remained faithful, and the dog unraveled his every trick, in brilliant relocations time-and-again—road-break-quarter-stick!—and to the hurrying young man who from the gradient above could see the sense and strategy of both, it was yet again a remarkable and glorious thing. As evermore the bird was pushed more closely toward the watery abyss of the swamp, where a year before he had pulled his miraculous escape from the gun by swimming and hopping the hummocks.

To the young man, again from above—the dog was brilliant beyond comprehension that day. It seemed from the pattern and pace—as the setter pushed just hard enough, stood just long enough—that the bird was being herded without ever knowing it, toward the obstruction of the swamp. For once the old bird looped, and reversed, tried to turn, tack back again uphill . . . and must surely have thought of flying…but the cover was so securely deep, and the dog had so beautifully and momentarily blocked, that his course was cunningly tempered anew, sending him fleeing ever closer to the swamp.

Afterward, and as always, some would say “Yes.” Some would say “No.” Only the truth exists, and the truth is that by fallacy of will or wander, the wily gray bird was now being driven to a place again, where he would find his back against a wall.

Hard pressed and sensing it, the old bird threw a final, novel and desperate card from his near-exhausted bag of tricks, and it was a consummate one. The Old Man was at last up again, where minutes before on the incline his son had stood, watching in wonder as it so superbly came to pass. As the younger man, now below, bumped, fell and stumbled furiously through the heavy cover, trying to maintain a near contact with the dog.

Leading the setter into heavier and heavier cover, clumped and clotted heads of wild rose and greenbrier, willow shoots, thigh-high grass, reed and vine, the bird now began running wider, figure-Ss, and hopping to the tops of the grass, low willow and shrub, to flutter 20 yards to a pause, and flutter twenty yards again. It was simply unbelievable.

But so was the setter, and today the conditions were his. He would not be beaten, and the gray bird, however crafty, could not shake him.

Now the gray bird was pressed against the water, and ran down its edge, as the setter again executed one masterful relocation after another—slamming to a halt each time the odds grew close, as abruptly as if you could stop the bullet from a gun—pressuring the bird with exactly the panache he had after so many encounters learned he could. As the old man, sensing the approaching climax, made his way diagonally down the mountain and into the surly cover as swiftly as he could, and his son struggled to stay ever close to the fray.

As on the battle between them drew, in a perfect storm, each round ending by again the clanging of a bell. Two fighters, unbroken—the dog pummeled and bloody, the bird almost exhausted, wit and wander, each throwing his last, stiff, devastating punches—for another 70 yards through Satan’s Garden down the rugged brink of the swamp. Into the covert known in grousing vernacular as “The Three Fingers.”

Until the setter broke off, raced around and magnificently diverted his opponent’s advance, and the gray bird, against the ropes, was turned to his last resort: the second peninsula of the swamp, which was thick with rose and thornbrier, clotted with matted grass and bent willow. It jutted another 100 yards into the morass, water every side, and the gray partridge used it all as perfectly as he could, but soon realized the error and peril of his plight. While still the tri-setter followed mercilessly—road, stick, bang!—until the old bird came literally to his Waterloo, and was jammed to bay with his back against the water. Holding pins-and-needles before the bold and rigid stand of the implacable setter.

At the very tip of the “second finger.” In the mud midst the thick, coarse stalks of the cattails, which constituted the last semi-dry piece of cover, beneath the velvet brown heads of the seed pods, now tattered, torn and strewn, bleached blond by wind and weather.

There he held, a great warrior now with resign in his heart, on the verge of doom at the difficulty of his situation, but refusing to surrender. Desperately seeking to sort out an option, a tactical counter-attack. While on went their stalemate, the King under siege, the Setter-Lord loftily in command of his court. On an endless few minutes wore, and there was nothing else in their world.

First Grouse by Rod Crossman

Finally the gray bird stooped, could take it no more, bunched to leave. To blast out of the reeds, roll over hard, and flash away, wing-tips dragging the very surface of the water. Should have. But this time—three years into his battle with the tri-setter—he at last made the single, decisive error. He waited too long. It was too late. For now he could hear the heavy, closing approach of a man, coming up briskly behind the dominant stand of the setter, on the land finger itself. Could hear the bluster of his progress through the brush, as he fought his way forward. Closer and closer, too close, with the gun.

It is a poignant matter of living, in the game of life and death, when one must lose, and one must win. Between two consummate warriors almost flawlessly matched, when never before in a lifetime, either has surrendered. Nor ever would.

The gray bird would never, and now he fought with only the final craft of his wit, asking no sword to fall on, and no shield to turn it aside. Only the wildness within his breast.

This time there were no hummocks to hip-hop, no line of tree cover masking his escape, no refuge of retreat beyond the one of imminent danger.

And now the man was up, advancing beyond the stiffly standing dog, and the old bird had nothing left, but the unremitting boldness in his soldier’s heart.

The Old Man strode steadily forward now, in front of the dog, to flush the last few feet to the end of the peninsula. The only place the old gray bird could be. He had vowed to be here—now—at the final end. Had almost killed himself in the doing, was shaken, torn, battered and bloodied, as if he had been in the fight itself—which, in fact, he had. He had earned the way here, as he had said he would. Three years of waiting, of hoping, for this great dog to at last conquer this magnificent and unyielding bird. And here it was. Today, unquestionably, had been the setter’s. Today he was the one that had reigned supreme.

Gun at port, the Old Man moved steadily ahead, kicking lightly at the brush, with only a scant expanse of cattails left between his boots and the water. Heart pounding, the thrill of the next explosive moment lodged in his throat, he was out-of-body and into the clouds, mesmerized with the moment, but 78 years of grouse-dues ready.

Ready as anyone could ever be, and still the gray partridge came up so suddenly, explosively, so violently, in such a staggering bewilderment of thunder, the Old Man was split-seconds recovering.

It was if the old gray bird, fighting to the last, had erupted in a final, spectacular episode of defiance. For he rose the color of snow out of the dark shadows of the cattails into the full, shimmering highlights of the afternoon sun, fully flared-and-fanned, against the jet black surface of the open water—in the regal and disorienting frontage of full display—throwing all caution to the wind, and reluctantly exhausting his last powerful residual of strength in a brave and daring show of retreat. Peeling hard left and away, and beating lustily for freedom.

And the Old Man was affected—as any man would have to be—but unfazed, and the worn Fox gun came smoothly to the old man’s shoulder, and was swung in unwavering and practiced precision before its target . . . steadily, perfectly, tracking past the bird’s flight.

After three years of battle, the struggle between the tri-setter and the gray partridge was suspended at eclipse for two suspenseful, cataclysmic seconds of utter silence. Before the old bird’s world would disintegrate.

But the perfect moment passed. With still no sound, absent the shot that would have folded the flags, and consummated the war. As the Old Man slowly lowered his gun, and together with the grandly swollen setter, watched the old gray warrior away.

The Old Man stood silently for a brevity more.

Death had become a younger man’s game, he admitted to himself. He was as the old bird, no longer a young man. But an old one, likened to living. Looking back one last time in the direction the old bird had taken, he gazed vacantly for a moment . . . then slowly lowered his head.

He went then to his dog, laid his gun aside, gently stroked the setter’s sides, and the two of them shared, not in words, but through the deeper liquid language of their enjoined eyes all that was left to be said.

The old gray partridge lived on.

They would never know what finally happened to him. Perhaps, at last, in an uncharacteristic moment of distraction, an owl. A fox. A coyote, or even a coon. Perhaps as the Old Man, the bird’s reflexes had grown no longer so good.

The next season came and passed—and the next—and still the tri-setter would time-and-again make for the great hemlock log on Tabernacle Mountain, hunt and hunt—the months through—for his venerated rival. The Old Man would not call him away, perhaps harboring in the end some faint hope that the old warrior still thrived . . . and their battle would be rejoined . . . in a different kingdom on another mountain. Even though he knew better.

Fact was, the old gray partridge was gone.

The tri-setter remained ever the great dog he always was, and for eight more years his legend lived and grew. Though never was tested so evenly again. And it was said, that even then, when he himself was old and gray—the January before he left to rejoin, wherever they had gone, the gray bird and the Old Man too—anytime he was cast by the old man’s son onto the sacred mountain, he never failed to hunt by the old log, as he remembered.

Dogs don’t stumble over regrets, but simply play out their days as they come. But clearly he missed the old bird, and his indomitable challenge.

Now, the setter too, was gone, and their day, in their way, would never be again.

The Old Man’s bones are given to the tiny cemetery behind the Tabernacle Mountain Baptist Church in the small Town of Campbell, where he lived and died, the old dog’s to a small gravesite by the great hemlock log on the sacred mountain, the old bird’s back to the mountain, somewhere near where he was born.

Over the old man’s grave stands a stone, and on that stone is carved his name . . . above the semblance of a partridge and a setter dog . . . and beneath them stand the words: “Called to the fairer coverts of Heaven.”

Above the dog’s grave, upon the sacred mountain, rests a stone as well, but upon it is found no name, only the crust of gray-green lichen that grows on its face. The blackened, old leather collar that was also placed there and its brass plate are long gone.

Though folks who remember say the setter’s name was “Logan.” In Old Gaelic, “Little Hollow.” In the field, the Old Man shortened it to “Lo.” “True, faithful, unswerving.” No dog better earned it.

The Old Man’s name was Thurlow Hayes; his son’s: Grant.

The gray partridge, had no name. But was, of course, no less part of the legend.

Without deeds, a name is of smaller matter anyhow. A name is at first only a word, and it is only through deeds that a word gathers memory and value. The more extraordinary the deeds the greater the story, and it is with word that we perpetuate that story, and it is in word, that memories and deeds are brought to last. Words are what we live by, and die by, and are remembered by.

It is words, not bones, that are deposited in the Great Bank of Eternity, and it is words that accrue through the years greater interest, that grow to validate the ever more precious memories that are compounded through the eons. It is through the incalculable value of words that we glean the strength and spirit to go on.

Partridge men come, and partridge men go, and to them rarely, will come the greatest of dogs, and the wisest of birds. And leave to us who care, their stories, the undying trust to carry on, so we are better served to live. While . . . Time and The River, roll on . . .

Author’s Note: This is a greatly condensed excerpt from the centerpiece novella of a soon to be completed book of the same title.

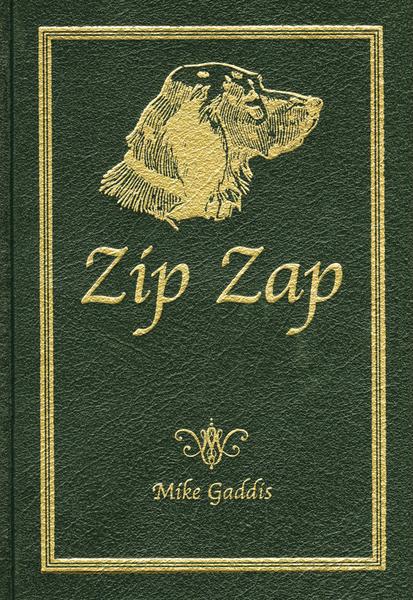

Zip Zap is a wonderful true-life story of a superb English setter and its litter-mates. On the heels of his highly-acclaimed novel Jenny Willow, Mike Gaddis reaches again into a half-century love affair with pointing dogs and upland birds to retrieve the true-life story of Zip Zap, his greatest English setter. Gaddis swore to be painfully selective in choosing the puppy that would accompany him as he pursued his dream of competing in horseback field trials. He knew the smallest female of the litter was special, but he didn’t fully realize her potential until he let her loose in the field. Her lightning speed earned her the name Zip Zap, and she grew to be the most brilliant bird dog Gaddis ever owned. In this absorbing memoir, Gaddis celebrates the dog’s indomitable spirit and tells the story of training and developing a superior pointer, from her first unrefined runs in the amateur puppy stakes to victorious performances in major championships. Evocatively told and set against the plantation quail hunting and field trailing legacy of the Old South, here is a rich, powerful memoir, certain to gain favor with anyone who has shared the destiny of a once-in-a-lifetime dog. Buy Now

Zip Zap is a wonderful true-life story of a superb English setter and its litter-mates. On the heels of his highly-acclaimed novel Jenny Willow, Mike Gaddis reaches again into a half-century love affair with pointing dogs and upland birds to retrieve the true-life story of Zip Zap, his greatest English setter. Gaddis swore to be painfully selective in choosing the puppy that would accompany him as he pursued his dream of competing in horseback field trials. He knew the smallest female of the litter was special, but he didn’t fully realize her potential until he let her loose in the field. Her lightning speed earned her the name Zip Zap, and she grew to be the most brilliant bird dog Gaddis ever owned. In this absorbing memoir, Gaddis celebrates the dog’s indomitable spirit and tells the story of training and developing a superior pointer, from her first unrefined runs in the amateur puppy stakes to victorious performances in major championships. Evocatively told and set against the plantation quail hunting and field trailing legacy of the Old South, here is a rich, powerful memoir, certain to gain favor with anyone who has shared the destiny of a once-in-a-lifetime dog. Buy Now