Duck shooting at its best has been to me an exhausting form of amusement, to say the least. For instance, there was the time we sat out in our blind at Hemlock Beach and had an intermittent rain pour upon us for ten hours, without a single bird coming to stool to reward our patience; meanwhile, we watched a couple of gunners in a battery out in the bay bag birds every few minutes. We could see a cloud of birds flying low over the water, head straight for this battery, and, with the uprising of the gunners for their shot, soar upward on hurried wings, while the sharp crack of smokeless and a couple of splashes announced the success of their shots.

We learned later that battery shooting had netted these gunners more than their share of birds, and I resolved then and there that my next try at ducks would be from a battery. The next trip took place on schedule time and in a battery, a single battery. It looked good to see the brant get up in clouds as we rowed out into the bay, and I could hardly wait until I was set out in shipshape order waiting for the sport to begin.

But it didn’t begin—not that trip. The birds were flying and seemed anxious to stool, judging from the bunch of brant that settled just out of gunshot from me, but as for me, I was too busy bailing out the battery to take a shot. A head fender that was too short in the choppy sea, coupled with a battery that leaked a bit, made me resolve once more to leave duck shooting for those who liked that strenuous form of amusement, and to stick to upland shooting.

But after you are home a couple of weeks and you get a letter saying the birds are flying, together with an invitation to take another crack at them, you remember the long tracks of salt marsh, the peculiar bracing tang to the air, you dream a bit, and—you’ve simply got to go again.

Well, the letter came as it usually does, and I went as I usually do. And as usual it rained. The greater part of the night was spent hoping the rain would clear off, fixing up the stool, and getting ready for the morning. It was still raining when we got up before daybreak; but rain or no rain, I was determined to see the bay anyway, so we harnessed the horse and, with the guns, stool, lunch, and the rest of the junk in the rig, set off for Babylon in the downpour.

The rain stopped after we got to the bay, and our spirits revived. Putting all the junk into a bag, we set off across the marsh and finally got into a small duck boat in which we intended crossing the bay, Jack’s sloop being hauled up for the winter. In the natural course of events we got set out, and things went along nicely. Jack got into a duck boat he had on that side of the bay, and after setting out a quarter of a mile or so to the windward, it began to look like we were to have the sort of a trip you read about.

There were six broadbills and a couple of black ducks under the salt hay at my feet when the wind started to blow. Of course, it had been blowing ever since we started out, but now it began to b-l-o-w blow. I was behind a small point of marsh and sheltered to a certain extent, but when the spray from the other side of that point began to splatter over me, I was not surprised to see Jack pull out from his exposed position and pole down to me. Just before he got there, a sheldrake came along, boring into the wind a few feet over the water on some very pressing business, judging from the way he was going. I felt duty-bound to pay my respects to him, and he tumbled prettily with a broken wing.

We had taken but one pair of oars with us, and in trying to get that sheldrake I snapped one of the oars at the blade—we found out later it was worm-eaten. Jack only remarked: “Looks like we’ll have to stay here till this breeze o’ wind goes down.”

By this time it was out of the question to try to shoot against that wind, or even lie in the boats, so we got on some dry seaweed 50 feet or so from the shore and had a smoke. We put our hopes on the wind dying down with the sun; but it wasn’t that kind of a wind, for when Fire Island light started to twinkle, it spat on its hands, so to speak, and started to blow “a livin’ gale,” as Jack said.

Since there was to be no chance for home that night, we started to make ourselves as comfortable as possible under the circumstances. The duck boats were pulled up on the shore and laid side by side. Four stout poles found among the driftwood, of which there was plenty, were used to form two inverted V’s, one at the bow and stem of each boat, and with another log for a ridgepole we had the skeleton of a hut. It only needed a bunch of small sticks running from the ridgepole to the ground and plenty of eelgrass, which can be found on any marsh on the Great South Bay, on top of that, and we had a hut that would at least shelter us from the wind for the night. All our food had been eaten at noontime, so we crawled into our huts supperless to find what comfort we could in a smoke.

Now when you crawl into a duck boat and shove your wet feet under the deck and lie in such a manner as to get some degree of comfort, you are up against it, no matter how tired you may be. Even though the bottom was covered a foot deep with salt hay, I can remember exactly how many ribs that boat had and just how far apart they were. There is no use telling how often we awoke that night—it was the longest night of my existence. It was only about 36 degrees above, and we were wet.

However, there’s an end to everything, and when I saw a faint, pink glow in the East, I jumped up and made a fire which we hugged to thaw out, for the wind was still doing business at the old stand. The pink glow chased the purple shadows away, and the stars grew dim. The opposite shore began to take form, and we could see the spires of Babylon through the haze. A meadowlark whistled, and a yellow-leg called querulously. Cold, hunger, and thirst were forgotten in the wondrous beauty of the sunrise, when the ducks began to fly.

As if by a signal, they came boring into the wind in bunches of six to a dozen, necks stretched, wings fluttering rapidly, and a never-to-be-forgotten picture—they were limned against the grayish blue of the cloudless sky; a picture that paid well for the hunger and weariness we felt.

Did I say weariness? It was gone at the sight of the birds. Gone, too, were hunger and thirst, to be replaced by an overpowering desire to get set out again for just one more try at them. The wind moderated long enough to get 14 when it started in all over again, so I concluded it was about time to make an attempt to get home. The broken oar was laced together with some cord from the anchors of the stool, and we started out in the teeth of the gale.

There is no need of telling how many times we stuck on the mud flats, or how the spray drenched us, or how the glare of the sun on the water blinded the oarsman, or how, when after a row of three and a half hours, the boat’s nose grated on the beach and we were too stiff to get up. I resolved then and there, no more duck shooting; but what a difference when we were washed, a good meal under our belts, a cup of steaming coffee at our elbows, and a pipe in our mouth! A feeling of content stole over us, and in spite of the tussle we had, “it was a good trip after all,” wasn’t it, Jack?

All this happened last December, and the old gun is in its case, well oiled and ready for use. For, in spite of my resolve to let duck shooting alone, I can’t forget how they looked as they came fluttering along, or the thrill I felt when the gun cracked, as they hung poised for an instant to fall with a splash that sent the ripples in an ever-widening circle.

Note: “When the Ducks Begin to Fly,” was first published in Outing magazine, 1909.

The North Atlantic, the Great Lakes, the Gulf Coast, the waves and the wind and the ducks – there’s no doubt that big water holds a lure for waterfowlers unlike any other.

The North Atlantic, the Great Lakes, the Gulf Coast, the waves and the wind and the ducks – there’s no doubt that big water holds a lure for waterfowlers unlike any other.

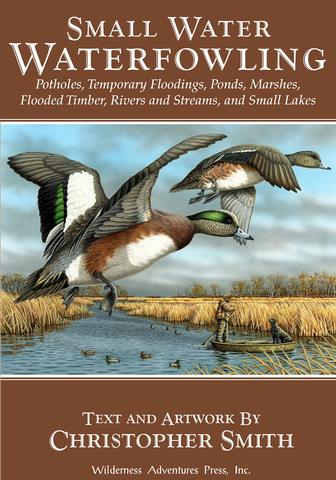

But when it comes to actually shooting ducks and geese over water, the action is on the small places – the inland lakes, the ponds and potholes, the floodings and creeks and backwaters. Day in and day out, that’s where the ducks are, and that’s where Chris Smith takes you.

However, each of these places requires a separate technique, alternate decoys spreads and calling concepts, and different gear to use. He tells you how to approach each type of hunting for the weather and conditions. He knows when and when not to call. He describes the skills a good waterfowl dog needs to know for each place, things he’s taught his succession of Labrador retrievers over the years.

His knowledge of duck and goose hunting has been earned through both experience and education. A native of Michigan, he holds a BS in Wildlife Management from LSSU in Michigan’s Upper Peninsula which, he jokes, “was a good way to go to class in the morning and duck hunt in the afternoon.” His love for waterfowl has come through in the 20-plus years panting wildlife in his “other” job, with four state duck stamp titles and two state Ducks Unlimited Sponsor Print titles to his credit, as well as placing high in the national event.

But what sets him apart is his skill, his knowledge, and his techniques accumulated over nearly four decades, a dozen states, and a half-dozen Canadian provinces.

In a spot where more is often viewed as better, Smith weaves throughout personal hunting stories the important roles ethics play for the modern-day ‘fowler, how a full bag limit isn’t the end goal, but rather icing on the cake.

In all, this is one of the finest treatises on waterfowling to come out in years—because small water means big sport. Buy Now