Here is the story of two different marshes, on two different continents, gunned within a month of each other. British driven duck shooting versus American over-decoys duck hunting; green, well-watered country versus desert.

In November I shot ducks in Scotland, and in December I hunted them in New Mexico. The contrast in climate and technique was striking. In Scotland the air was humid and tasted wet; there was mud underfoot. The hooves of animals made deep tracks in the ground, and the tracks filled with water. The fields were green, very green; the hills were lost in moist clouds. Rainy country.

In New Mexico the air was dry. It smelled dry and as you inhaled the dryness crept into you. Tracks of animals and birds were outlined on the dusty ground, soon to be partially filled in by the wind. The desert was brown and grey with only a touch of green. Thirsty country, country that longed for water.

Dave Tilden had organized our trip to Scotland. In the morning of our first day, we followed Jay’s Land Rover into a farmyard. The parking area was damp and muddy; there were tractors and parts of very well used equipment scattered around the edges. This was a working farm, a place more interested in results than looks. We walked past hanging pairs of ducks into a section of barn and were greeted by our hosts who offered us coffee and hot sausage biscuit sandwiches. A red-hot wood stove helped us shake off the dank of morning.

I’d signed on expecting to shoot pheasants and Spanish partridge – and we precisely did that; however, at the end of our first outing I got an unexpected bonus. The last drive of the day was a duck marsh. There were the occasional flushed pheasant and snipe flying out of the shallow edges, but there were two hundred mallards in that marsh just splashing, feeding, flying and swimming. Some were in view, others were hidden in the swamp grass and high reeds. We were going to drive that marsh.

Our Shooting Party, still wet, L to R : Taylor Thompson, Randy Croote, Ron Shepherd,Bob Sohrweide, Jay Steel,Pete Stanley, Dave Tilden, Russ Hughes, Brian Fawcett

Jay Steel organized us. After most of a day’s shooting she had some idea of both our physical and shooting limitations. All of us were very good shots, but some shooters were more beat up than others. I and my aching knees got a ride in a field buggy to my post. Others got lifts or walked to their locations. The drivers would wade into the marsh from my left. Our party of eight hunters split up to cover three quarters of the edge of the marsh. Anything flying out of that swamp would be in range –high, low, close or long – of one of us. This would not be the duck hunting over decoys we American gunners were used to; this was duck shooting. The birds would flush from the marsh at speed, traveling in all directions. All of us would have shots.

I was at the far left of the U-shaped line. Ron Shepherd was on my right; Randy Croote was on his right and then the line curled around the end of the marsh and along its other side. Jay positioned herself between and behind Ron and me. We were standing on a slight rise about fifteen yards from the edge of the marsh. A light screen of brush and short trees kept us out of sight of the ducks. We waited. Watched the beaters in their wellies and hip-boots wading through the edge of the marsh, picking their way through the mud, water, lumps of swamp grass and waist high brush into the deeper parts of the marsh. Labrador retrievers splashed, plunged and swam by their owners’ sides.

Wet and Green.

I reminded myself what Jay had said to all of us: “Blue sky rule, shoot only at birds surrounded by blue sky. No low shots or ground swatting cripples, there will be drivers, dogs and other shooters out here. Leave the cripples for the dogs. Shoot them in the air and in the face.”

Jay signaled to load up. I slipped high brass fives into my borrowed W & C Scott side by side and smiled. The sixteen bore was choked modified/full, close to perfect for medium to high ducks. It was a fast, responsive shotgun. I envied Ron Shepherd, the gun’s owner.

Dave Tilden opened the ball. I watched a high greenhead fly to the other edge of the marsh, fold up at his shot and hit the grass behind him. Another shot came from across the way. Then another. Four mallards flew over Ron, I smiled at his right and left — two birds dead in the air.

“Leave the cripples for the dogs.”

Jay yelled, “Bob, left, left.” I looked left as I brought my gun up and saw a single curling away. “Hit ‘em in the head,” I muttered to myself, got in front of the bird and crushed it.

“Look right, right.” Jay called. I slipped as I twisted in the sodden grass and saw five birds flying high and fast between Ron and me. I managed to drop one with my second barrel. More shots came from across the marsh where Brian Fawcett and Pete Stanley were at work. I saw ducks falling and splashes as dead birds hit the water.

The drivers were approaching the middle of the marsh. Birds were in the air flying across, over and behind us. Fast incomers, high curlers, crossers. Left, right, overhead. Jay spotted for us and kept Ron and me informed. The trickle of birds turned into a flood, and we had ten minutes of fast, joyous, adrenaline driven shooting. The dogs and beaters picked up fifty ducks. Twenty-five brace!

A month later Jim Heath and I were in a blind alongside a marshy pothole in the Chihuahuan Desert, waiting for sunrise and ducks.

Jim is my best friend and oldest hunting partner. When we both retired from our jobs in Northwest Connecticut, I moved north to New Hampshire and he moved west to Arizona. We had long talked of hunting together in the Southwest. Over a year ago Jim had found a highly recommended guiding operation in New Mexico. We booked a combined duck and quail hunt for this December, an early Christmas present for both of us.

The owner of the guiding operation, Bob King, met us in Truth or Consequences, New Mexico (yes, there really is a town of that name, see Google for the complete story). We hunted Scaled and Gambel’s Quail on our first day. The desert was bleak and beautiful. Bob warned us as he drove down dusty two tracks, “This is the Chihuahuan Desert. All the bugs bite, all the reptiles are poisonous and all the plants have thorns.” I thought back to the more friendly green and wet acres of Scotland in November and laughed. What a difference a month and a continent can make.

We moved some birds, and I watched Jim make a bragging about left to right crossing shot on a fast-moving Gambel’s. These were wild birds and they flew much faster than plantation raised bobwhite. Jim’s quail had flushed in front of Bob’s German Shorthair; Jim’s first shot was behind but his second shot centered the bird. It collapsed in the air and, carried by momentum, thudded to the ground forty yards away. That cock bird was dead on arrival. I had the great pleasure of a ringside seat to the whole affair and shouted my congratulations. I then walked over and got my first close-up look at a bird-in-hand male Gambel’s Quail. Simply beautiful.

On the morning of our second day – the very early morning – Bob drove us into the desert after duck. “The duck have been roosting in the Rio Grande and then flying into the desert to feed. After their breakfast they like to come to these potholes. A bunch have been using this one.”

We set up in the thorn thicket bordering the marsh. Bob put out six decoys to our right and two dekes to our left with a nice open landing area in between. He set up netting over our heads. We sat in folding chairs and waited for dawn. If we stood, our heads would be in the camo netting. We’d have to shoot from a sitting position, something both Jim and I were used to doing.

Bob left us to move his truck out of the area. “You will be legal in five minutes.” We watched, waited and then heard the sound of whistling wings behind us. A flock of dimly lit teal flashed across the marsh in front of us. More whistling as they circled again and again, finally settling into the decoys on the left. One of them was right in front of me; the others were screened by the brush to my left. Cinnamon teal. Suddenly, they jumped into the air and were gone in a flash. We got our guns up to our shoulders and took one long shot apiece. Misses. We both were shooting 12-gauge pumps and before we chambered our second shells those teal were long gone. We were left shaking our heads. Those birds were fast and wary.

Chihuahuan Desert: Dry Country

Full light came and I got a good look at our surroundings. Shallow water with weeds. Brown sand. Baked mud. Some withered marsh grass. A bit of green in the thorns.

Fifteen minutes later a single flew right into the decoys. As it hovered just above the dekes, we both fired. We both hit it. We both were overeager after our teal experience. That duck did not stand a chance. It floated in a clump of marsh grass – a hen shoveler – a bird we had not seen in our eastern shooting. Pleased that we had broken the ice, we worked out our shooting lanes. I would take the right-hand birds, Jim the left. We waited.

Marshy pothole with decoys.

Two mallards flew past. I blew some soft chuckles on my Haydel call and they circled back for another look. Another soft chuckle and they set their wings coming into the wind and into our faces. Hen on the left, greenhead on the right. Jim and I shot together and both birds folded and dropped. Splash one and splash two, fifteen yards apart. We picked up our empties and tucked them away. The sun was starting to shine brightly but it was behind us and we were in the shadows under camouflage. This was a welcome change from our usual hard-luck sun-in-the-eyes duck hunting location.

The harsh desert conditions were new to me. Sand, thorns and sun. But ducks still flew and came to water. And we were set up along the marsh in an ideal spot., camouflaged, shadowed and with the wind blowing so that when the ducks came in, the sun was in their eyes. And several more duck did come in. Shovelers and mallards. We shot and downed birds. We shot and missed. Some flocks blew past us without a look. The teal did not come back, but we were happy with the occasional big mallard or smaller shoveler.

“I’ll send the dogs after those duck out there…”

The action stopped around nine fifteen. Jim and I talked and reminisced, of past hunts, old dogs and hunting partners. A duck blind is a fine place to catch up. I told Jim about the birds of Scotland, and he told me about life in the Southwest. Wet and green contrasted with dry and brown.

Bob arrived at 10 o’clock. He had spent the time scouting for ducks. “I’ve got another nice pothole for tomorrow. Greenheads and teal. I’ll send the dogs after those duck out there, and then we’ll hunt quail.”

Bob had three German Shorthair Pointers with him, ready to hunt quail. Following Bob’s hand signals and splashing through the shallow water, they retrieved our ducks. Waterfowl were not the GSPs’ main order of business, but they were eager and willing to help, and quickly brought in the birds.

We moved away from our duck marsh, into the New Mexican desert, following the dogs, who were looking for quail.

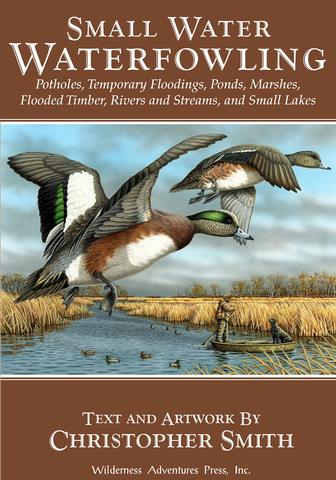

Small Water Waterfowling: Potholes, Flooded Timber, Rivers, Streams, Beaver Ponds, Wild Rice, Small Lakes, Farm Ponds & Temporary Floodings The North Atlantic, the Great Lakes, the Gulf Coast, the waves and the wind and the ducks – there’s no doubt that big water holds a lure for waterfowlers unlike any other. But when it comes to actually shooting ducks and geese over water, the action is on the small places – the inland lakes, the ponds and potholes, the floodings and creeks and backwaters. Day in and day out, that’s where the ducks are, and that’s where Chris Smith takes you. Buy Now

Small Water Waterfowling: Potholes, Flooded Timber, Rivers, Streams, Beaver Ponds, Wild Rice, Small Lakes, Farm Ponds & Temporary Floodings The North Atlantic, the Great Lakes, the Gulf Coast, the waves and the wind and the ducks – there’s no doubt that big water holds a lure for waterfowlers unlike any other. But when it comes to actually shooting ducks and geese over water, the action is on the small places – the inland lakes, the ponds and potholes, the floodings and creeks and backwaters. Day in and day out, that’s where the ducks are, and that’s where Chris Smith takes you. Buy Now