That is the role Duxbak attire played in sporting experiences not only for me but for my friends and untold legions of others who once would have felt semi-naked without this venerable attire. Babcock wore Duxbak; everyone who accompanied me afield from my earliest experiences with squirrels, quail, grouse and rabbits wore it; and for two or three generations prior to the advent of camouflage clothing it was de rigueur for hunters across the Southern heartland and beyond. Tough as a seasoned hickory stick and stiff enough to battle the worst that dewberry vines, blackberry briars and sawbriars had to offer, Duxbak gear enjoyed the additional virtues of being water repellant and incredibly durable.

During my 1950s boyhood, most any weekday from mid-October through February found me donning Duxbak as soon as I could rush home from school. After hastily changing clothes, I would grab a leftover sweet potato or a piece of cold cornbread and raw onion for a snack, stuff two or three apples from our little orchard in the capacious pockets of my hunting jacket (as a greedy-gut boy I wasn’t about to get peckish), and head for the woods.

Any game bird or animal in season was a worthy quarry for a Duxbak-clad boy, and the only variance in my daily roaming from mid-afternoon to trudging homeward in the gloaming involved slight clothing adjustments. As it got colder long johns would be worn beneath Duxbak britches, and the sleeveless shell vest of October’s Indian summer days gave way to a heavy jacket with pockets galore and a capacious game pouch. On rainy or snowy days there would be an adjustment in headgear as well, with the normal Duxbak topper featuring natty sides folding away from the cap’s brim being replaced by a Canadian Mounties-style hat which fully protected one’s face and neck from the elements. Even in warmer months a Duxbak cap was worn the way baseball caps are today. In time these would sport visible sweat stains, but far from being unappealing or unsuitable in a youngster’s eyes, such distinctive headwear served as a badge of honor offering visual testament to long and loving use.

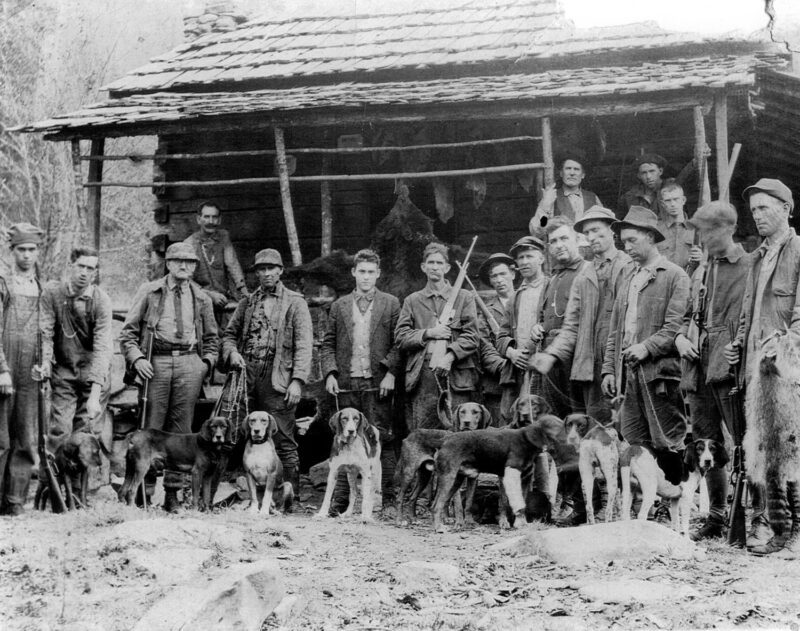

A group of hunters at the Bryson Place (Deep Creek, NC) circa 1920. Photo courtesy Jim Estes.

Mind you, on one occasion my being partial to Duxbak head coverings got me in considerable trouble. To represent myself in the most charitable light, I was a bit of a rapscallion as a teenager, and wayward behavior found me in some type of trouble all too frequently. In those days corporal punishment was still permitted (and employed) in public schools, and I had a ninth grade English teacher who periodically threatened miscreants with “six of his best” with a razor strop. Some transgression of mine earned deliverance of six licks, but when the teacher went out of sight to get his strop, sudden inspiration led me to grab the Duxbak cap I had stowed beneath my chair and tuck it in the seat of my pants. I figured the stiff fabric would lessen the impact of what lay in my immediate future.

Unfortunately the cap left some kind of tell-tale bulge, and the teacher whipped the daylights out of me. He actually left bruises on my posterior and such an action would, in today’s world, probably have resulted in his dismissal, threats of lawsuits and the like. For my part, there was no doubt whatsoever I deserved the six licks (although I don’t recall my particular bit of waywardness on that occasion), and I certainly wasn’t about to relate any details to my parents. That would simply have resulted in further punishment. However, that was the sole occasion Duxbak ever let me down, and I owed the situation to nothing more than adolescent idiocy.

Call me old-fashioned or a product of a time when the mindset of educators and parents was misguided, but let me assure you that spanking was merited, needed, made a lasting positive impact, and enhanced my admiration for the man who administered it. The bruises soon vanished but the event and the Duxbak cap involved therein left lasting memories.

My earliest outdoor recollections likewise include Duxbak memories. Initially there were hand-me-downs Mom somehow tailored and refitted from pants Dad had worn until the bottoms frayed, although that meant the britches had seen several seasons of use and untold miles of confrontation with brambles of every sort along with frequent encounters with Beelzebub’s favorite vegetation, floribunda roses. How she ever managed to sew that tough, thick cloth remains a mystery, as does the manner in which she reduced the waistline and crotch on a man’s attire to fit a small boy, but Momma was a staunch adherent to the Depression-inspired philosophy of “make do with what you’ve got,” and she worked wonders on her trusty Singer sewing machine.

When I finally reached the point where pants that fit me could be purchased, rest assured no banty rooster ever strutted more proudly than I did in the Duxbak britches and a cap I received as a Christmas gift when around the age of ten. A year or two later Dad found a jacket to fit me. What a treasure that was with voluminous side pockets suitable for storing shotshells, gloves, maybe a hunk of rat cheese, or much more food if I was off on an all-day hunt during Christmas vacation or one of those blessed times when it snowed and school closed.

It was comforting to know that no matter how much ground you covered by shank’s mare, no matter how many calories you burned, that trusty coat would tote not only game but the provender to keep you going. Each and every pocket had its purpose, but it was the game pouch in the back that was truly special. It expanded enough to hold a thermos, a poke stuffed full of sandwiches and sweets for your field lunch, or, if Dame Fortune had seen fit to smile brightly on a given day, a limit of squirrels or three or four rabbits.

From the time l had grown sufficiently to wear catalog-order pants right on through high school and undergraduate college years, alternating Yuletides found me receiving a new pair of Duxbak britches. In the intervening year Mom would take material from the upper legs of worn out pants and lovingly stitch the heavy fabric to my current pair where they had begun to wear away at the bottom. Thus outfitted I marched afield with pride and, from my decidedly parochial perspective, as suitably attired as any British squire wearing tweeds and cradling a high-grade double barrel.

Never once did Duxbak fail me when afield, and from the company’s beginning in 1904 until it went out of business many decades later it set a high standard for American sportsmen. Pay close heed to vintage photos or artwork of hunt camps and field scenes. No matter the sport, you will soon realize that Duxbak ruled the day, at least in the South.

Two personal examples attest to this. One is a faded, cracked photograph of a large party of pre-Depression era bear hunters, perhaps thirty in all, in my possession. Almost to a man they wear one or more items of Duxbak. The second is a rather fuzzy, poorly focused image from my adolescence, likely taken by my father, showing me and a bunch of my buddies, along with a bevy of beagles and one adult clustered around a Jeep. All of us are wore Duxbak from head to foot.

While the gear did its job in the field and for that matter astream as well, it’s possible that what was arguably Duxbak’s greatest virtue, incredible durability, also figured in its downfall. Merle Haggard’s lyrics in his classic song, “Are the Good Times Really Over?,” lament that American-made automobiles no longer “last ten years like they should.” That may well have been the case, but in its heyday there was no question about Duxbak wearing and enduring like it should. One has to wonder whether the clothing was so well made that its lack of “planned obsolescence” actually led to the company going out of business.

On a personal level, all I can say is that for me, during those halcyon years of adolescence and beyond, Duxbak was in its own fashion as faithful a friend as loyal canine companions or hunting buddies of many years standing. Like my first gun, the first trout I caught on a fly, the first squirrel I killed and so many other momentous happenings of a boyhood devoted to the outdoors, dreams of Duxbak days run as a sparkling thread through the entire fabric of my mind.

eteran cookbook authors Jim and Ann Casada share 400 field- and kitchen-tested recipes, along with dozens of sauces and marinades, that span the spectrum of venison cookery. From traditional favorites to gourmet and ethnic specialties, this is a complete cookbook with recipes for choice cuts and ground venison, soups and stews, sausages and jerky, and meatballs and chilis, along with offerings for slow cooker, casserole dish, and grill.

eteran cookbook authors Jim and Ann Casada share 400 field- and kitchen-tested recipes, along with dozens of sauces and marinades, that span the spectrum of venison cookery. From traditional favorites to gourmet and ethnic specialties, this is a complete cookbook with recipes for choice cuts and ground venison, soups and stews, sausages and jerky, and meatballs and chilis, along with offerings for slow cooker, casserole dish, and grill.