I’d been following my Brittany, Tess, through the steep, rocky canyons of southeastern Arizona’s Coronado National Forest for the better part of an hour when her bell fell silent. I found her upslope—bug-eyed, trembling and stretched out on point—at the base of a live oak tree. As I climbed up to reach her, I tried to keep my eyes focused out ahead where the birds would be likely to fly. But when the expected flurry of wings didn’t materialize, I couldn’t resist looking at the ground in front of Tess. Just as the striped face of a pretty little male Mearns’ quail popped into focus, he blasted off the ground along with the rest of the covey.

National forests in southern Arizona and New Mexico provide Mearns’ habitat as well as public access.

In the few seconds it took me to re-focus, most of the birds had darted behind the foliage. But I got off a quick shot at the last one as it slipped through an opening in the branches and saw a few feathers float down—always a good sign. Tess disappeared into the undergrowth and emerged after a quick search with a lovely cock quail in her mouth. I had a twinge of regret and hoped it wasn’t the bird whose soulful eye I had glimpsed as it squatted on the ground with its compadres a few minutes before.

I stopped and poured Tess a drink in the folding dish I carry while I admired the chunky little bird in my hand. It had white polka dots on its sides, a mahogany breast and a black belly and rump. Its striped face and pale blue beak gave it a clownish look, which explains why it has sometimes been called the harlequin quail. But then, the Mearns’ quail has been a bird with many names: crazy quail, fool quail, massena quail and Montezuma quail, the latter being favored by taxonomists. To Mexican hunters, or cazadores (Mexico is the heart of the Mearns’ quail range in North America), he is simply called codorniz pinta, the painted quail. Hunters in the U.S. have always known him as the Mearns’ quail, in honor of Dr. Edgar Mearns, a U.S. Army surgeon and naturalist who described the species in 1885.

Even though these feathered rockets seldom fly more than 100 yards, they’re good at hiding and often hard to find and flush a second time. But after 10 minutes of combing the cover, Tess locked up on point and two birds zipped from the knee-high grass when I moved in. I took the one that offered the clearest shot, a cinnamon-colored hen. In hand she had an almost pinkish tinge with brown and black markings. Like the male, she had curved claws about a half-inch in length; the birds use these toenails to rake the forest duff for tubers, wood sorrel bulbs and insects. Since there had been only about eight birds in the covey, I decided to leave the rest for seed and move on to look for another bunch.

It felt great to be hunting Mearns’ quail again, a bird that has flown in and out of my life for the past 40 years. And it felt especially good to have the warm Arizona sun on my shoulders instead of the cold winter wind back in my home state of Montana. Mearns’ quail have always seemed exotic to me, partly due to the stunning plumage of the males and partly due to the nature of the border country itself: steep, oak-clad mountain ranges populated by Coues deer, mountain lions, diamondback rattlesnakes, javelina, raccoon-like coatimundi and even the occasional jaguar. Then, too, there are the drug smugglers who sneak across the border from Mexico. Even the names of the “sky island” mountain ranges where Mearns’ quail live seem exotic: Santa Ritas, Huachucas, Chiricahuas, Patagonias, Baboquivaris and several others.

I started my Mearns’ pursuit back in the 1970s thanks to outdoor writer Charley Waterman, who included a short section on them in his book, Hunting Upland Birds. Talking one day to Charley at his summer home in Livingston, Montana, I asked him about the Mearns’, which back in those days wasn’t even a blip on the radar screen of most bird hunters. Charley told me they hold for pointing dogs just like bobwhites and that I wouldn’t have much competition from other hunters since on the U.S. side of the southern border they live only in a scattering of mountain ranges in Arizona, New Mexico and Texas. That was all I needed to hear.

That winter I headed south with a friend in a truck loaded with dogs and camping gear. We eventually landed a stone’s throw from the Mexican border and found good numbers of Mearns’ quail tucked away among the canyons and grassy hillsides of the Coronado National Forest. I’ve returned many times in good years and bad—Mearns’ numbers fluctuate from year to year depending on abundance and timing of summer monsoon rains—but I’ve always found enough birds to keep me and my dogs happy. Times have changed, of course, and over the years the Mearns’ has transitioned from a curiosity to a sought-after trophy—a bird on the bucket list of many avid wingshooters.

Before making that first trip in the 1970s I hadn’t found much written about the Mearns’ except for Waterman’s short description. I later found that Jack O’Connor had included a chapter on the Mearns’ called “Mystery Quail” in his 1939 Derrydale Press book Game in the Desert. O’Connor, born in Nogales, Arizona—in the shadow of the mountain ranges where Mearns’ quail reside—had never hunted them in his home state, since Arizona didn’t open a hunting season until 1960, well after Jack had moved north to Idaho. But he did encounter them—and hunt them—in the Big Bend country of Texas and perhaps in Mexico as well.

The striking beauty of the male Mearns’ makes it a sought-after trophy for upland bird hunters. Note the long toenails the bird uses to dig for bulbs and tubers.

In “We Shot the Tamales,” a story about deer hunting in the mountains of Sonora, Mexico, O’Connor mentioned his wife, Eleanor, hunting Mearns’ quail: “One day when we hunted high in the mountains in a region where cattle seldom ranged and the rich gramma grass was belly high to a horse, Manuel saw some Mearns’ quail scurrying through the grass. He was carrying the shotgun on his horse for us that day, so Eleanor piled off and went on a quail hunt there at 7,000 feet elevation on the grassy slope of a big peak…. For a quail, he has a very large breast, tender, delicious, faintly flavored with all manner of wild and wonderful things.”

While it’s not unusual for seasoned Mearns’ hunters to occasionally see a covey squatting on the ground in front of their dog, as I did with Tess, don’t get the idea that hunting them is easy. With their long wings they are even faster fliers than their desert cousins the Gambel’s and scaled quail. They burst from the cover like shrapnel and reach speeds of 20 miles per hour in a heartbeat. Like ruffed grouse, they have a habit of dodging behind a tree just when you’re about to pull the trigger.

The terrain, too, works to the birds’ advantage. While you may get lucky and catch a covey in the open, much Mearns’ habitat is steep, rocky and forested with oaks, junipers and a variety of shrubs. Imagine hunting bobwhite quail on a chukar slope—one covered with trees—and you’ll have an idea of what it’s like to hunt the codorniz pinta. All that, plus the fact that the birds live at elevations above 4,000 feet, guarantees that a day’s hunting will wear you and your dog to a frazzle.

Aside from the challenging terrain there are other hazards awaiting you and your dog in the mountains of southern Arizona. An assortment of prickly plants will snag your clothes and shred your flesh, especially the catclaw mimosa, otherwise known as wait-a-minute thorn. Javelinas are common and stories of dogs being torn up by them will curdle your blood—ask any local veterinarian. I have a friend whose German shorthair got in a fracas with one that ended in an $800 trip to the vet’s office to get the dog sewn back together.

Although the javelina resembles a pig, it is actually a collared peccary, a New World mammal only distantly related to the pig family. Built like miniature Abrams tanks, adult javelinas stand about two feet tall and weigh 35 to 55 pounds. Social animals, they live in family groups and defend themselves and their young with long, razor-sharp canine teeth (tusks) that protrude from the jaws about an inch—bad news for any dog that tries to whip one.

I chalk up my (so far) good luck in avoiding javelina trouble to putting bells on my Brittanys to prevent surprise encounters and training them to leave anything bigger than a rabbit alone. But dogs will be dogs, so you never know what’s going to happen. Speaking of leaving things alone, you may want to run your dog through a snake-avoidance clinic prior to hunting in the Southwest, something I’ve done and recommend. While rattlesnakes are denned up during winter in Mearns’ country, there is always the odd chance of running across a diamondback out sunning itself on a warm winter afternoon. Western diamondbacks get big—as much as six feet or more in length—and pack a heavy load of venom.

After eating lunch on the tailgate of my truck, I started up a canyon where I’d found a Mearns’ covey or two in years past. As I picked my way along the rocky bottom listening to the tinkle of Tess’s bell, I saw a couple of Coues deer, the little whitetails that Jack O’Connor thought the handsomest of all deer, their white flags flashing through the scrub as they moved up a side canyon.

As the sides of the canyon grew steeper, I thought of the late author and part-time Montanan, Jim Harrison, who spent his winters in southern Arizona for many years. I had the good luck to run into him in a small-town cafe near Nogales on one of my early trips. Between bites of his breakfast huevos he generously gave me a rundown on nearby places to look for Mearns’quail. He loved hunting them with his English setters and once described the precipitous nature of Mearns’ country in an article for Field & Stream: “Tess had pointed a few feet below the crown of a hill too steep for us to scramble up, then held the point as she slowly slid backward some hundred feet or so to the bottom where we stood. We call this being staunch to the point.”

About then my own Tess went on point beneath the spreading branches of a live oak 75 yards up the slope to my left. Gasping for air, I struggled up the hill to reach her, hoping I’d get there before the covey grew nervous and flew. My luck held and I downed a cockbird with my Browning Model 725 Feather over/under as the bevy roared off the ground. Choked skeet and improved cylinder and weighing a bit more than six pounds, the Model 725 had proved comfortable to carry and well suited for close-in shooting throughout my trip. A quick search for singles yielded another rooster, and since my feet and ankles had begun to cry for mercy from constant twisting and turning in the rocky terrain, I decided to call it a day. Tired but happy, Tess gathered up the bird and pranced back with it held gently in her mouth. Partway to the truck we stopped to rest near a lonesome windmill where I’d once seen a coatimundi scamper up a tree. I took the two quail from my vest to look at them again, marveling at their striking plumage, slender legs and comically long toenails.

As I sat there in silence, I thought for a time of Charley Waterman and Jim Harrison, the two men who had given me advice during the early years of my Mearns’ pursuit. I thought, too, of Jack O’Connor, a man I’d never met but always greatly admired, and whose classic stories of the Southwest had given me so much pleasure. Then I tucked the quail in my vest, whistled up Tess and headed for the truck where a cooler with a beverage suitable for toasting good writers, good dogs and a great game bird awaited.

This article originally appeared in the 2022 September/October issue of Sporting Classics magazine.

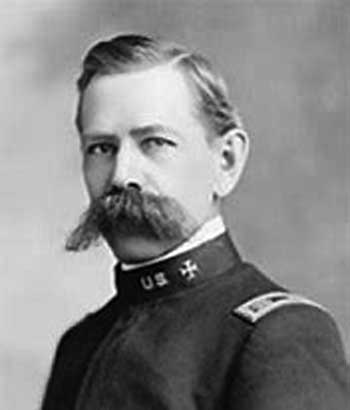

Dr. Edgar Alexander Mearns (1856-1916)

A friend and confidante of Teddy Roosevelt, Dr. Edgar Mearns crammed a lot of living into his 60 years. A U.S. Army surgeon whose passion was natural history, he first encountered the bird now named in his honor while serving under General George Crook at Fort Verde in Arizona Territory in the 1880s: “They ran and flew a short distance alternately until well up on the steep hillside of sliding rocks that were covered with long grass and low scrub oaks, affording the very finest kind of cover. As I clambered up this difficult slope, one after another they flew up before me always from right in front of me, uttering their singular notes and generally taking me when I was badly balanced and unprepared. I got three shots and brought down two birds, a pair.”

Born in Highland Falls, New York, Mearns formed a boyhood friendship with Teddy Roosevelt and later in life accompanied Roosevelt on a hunting and scientific expedition to Africa. Roosevelt regarded Mearns as “the best field naturalist and collector in the United States and a superb shot.” Born a few years apart, both men died at age 60 after lives of extraordinary accomplishment and adventure.

Born in Highland Falls, New York, Mearns formed a boyhood friendship with Teddy Roosevelt and later in life accompanied Roosevelt on a hunting and scientific expedition to Africa. Roosevelt regarded Mearns as “the best field naturalist and collector in the United States and a superb shot.” Born a few years apart, both men died at age 60 after lives of extraordinary accomplishment and adventure.

Despite being small in stature—Mearns stood about five feet, four inches tall and weighed 140 pounds—he possessed tremendous energy and unflagging zeal in collecting and cataloging plant and animal specimens from such far-flung places as Arizona, Texas, California, Florida, Minnesota, Rhode Island, Yellowstone National Park, the Philippines and Africa. On Mt. Kenya alone, Mearns and a companion collected more than 3,000 birds, mammals and reptiles for the Smithsonian Institution. Among his many accomplishments, Dr. Mearns co-founded the American Ornithologists’ Union (AOU), wrote 125 papers on biological and archaeological subjects and had at least 50 plant and animal species named in his honor.

After Dr. Mearns’ passing, The Auk, the quarterly journal of the AOU, carried a memorial tribute to him that concluded with these words: “Serene and placid in disposition, cheerful and optimistic in temperament, he was fond of the beautiful in nature and art…. As a friend, he was sympathetic, generous, steadfast and intensely loyal.”