Pronghorns offer one of North America’s finest sporting opportunities. Spotting and stalking these high-plains drifters is just plain fun!

Confession, at least in open form, is said to be good for the soul. With my particular soul being in dire need of the slightest good that might come its way, there is something I need to get off my chest. As a hunter, I’ve been ignoring pronghorns for many years.

Since I live in Montana, that might come as a surprise, but opportunity for other species is the reason for the cold shoulder. After all, with over-the-counter tags for deer, elk, black bear, cougar and wolf, we fortunate residents can hunt for something or other much of the year.

Pronghorns can only be pursued on a drawn permit, at least by Montana’s rifle hunters, and the high-odds areas are a long day’s drive from my home in glacier country. Pronghorn season also sits high on the shoulder of that for deer and elk, so I’ve simply put in for the nearest pronghorn area mostly to gain a bonus point and never given it a second thought. After all, it is a pretty tough draw and those other species stand higher on my wish list.

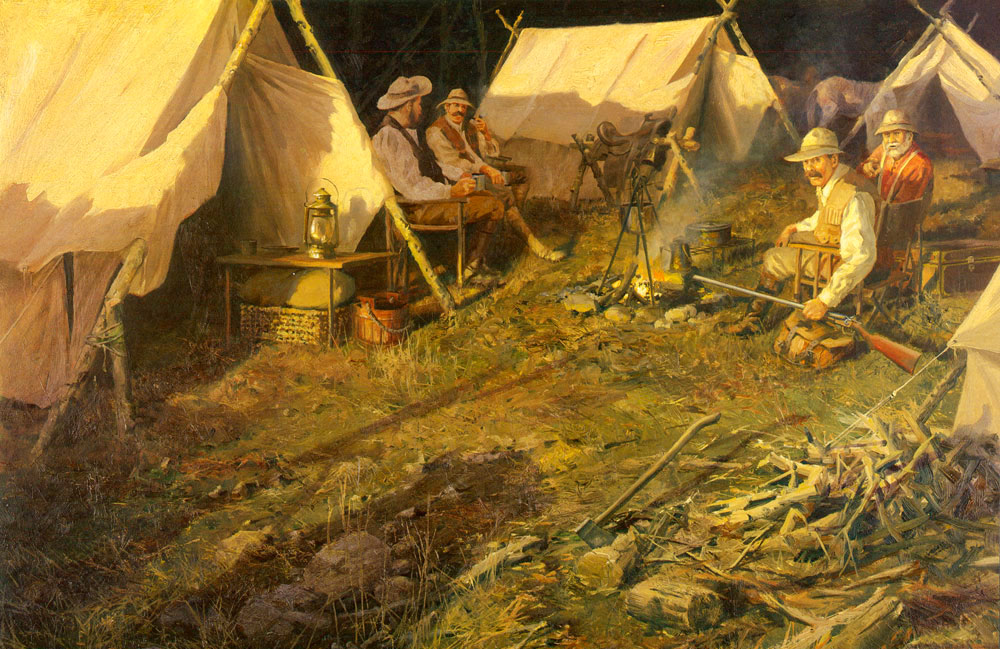

One year, results were posted and I learned that a pronghorn permit was coming my way. A quick review of the calendar showed no conflicts, and my family agreed it a suitable excuse to make plans. After all, pronghorn meat is toothsome, and those joining me could archery hunt for elk in some of the nearby drainages. When it was time, we threw together an outfit and made our way to the hunting area near Deer Lodge. It has been a long time since I’ve had that much fun.

My son, Ross, is the best kind of hunting partner. He has great game eyes and never runs short of enthusiasm. As soon as everyone was settled at a little roadside motel, we headed out to scout the intended area and somewhere along the way discovered my permit was for the other side of the highway.

Having never hunted the properly designated unit, I was in something of a lather, but Ross just opened up his laptop and found a nearby block management area that seemed likely. Before last light, we had located a pair of suitable bucks and more than a few other hunters. I went to sleep worried not about success, but about how we might stay out of everyone’s way and make the most of the opportunity.

Opening morning found us parked on a high overlook with nary a pronghorn in sight.

“Let’s just go walk one up,” Ross suggested. “It seems like the other hunters are semi-attached to their trucks.”

Off we went, and over the next couple of hours came up empty.

“Maybe we should drive up there,” said Ross, gesturing to a distant point. “If that doesn’t work, we’ll just move and glass and keep at it until something turns up.”

Before we gained the new vantage, a herd with two decent bucks scrambled across the dusty two-track, hit the afterburners and disappeared into a far valley. We shouldered packs and went after them.

After about 30 minutes, Ross spotted pronghorns, several does and one of the bucks, so we ducked into a contour and cut the distance. Already restless, we found them scuttling around the side of a mound.

“Get ready,” Ross hissed. “I’ll check the range, but I think you can do it.”

I laughed out loud at this dramatic reversal of roles, and then dug in my elbows.

“The buck is third in line. He’s at 400, no, 403 now. Take him when he stops,” he whispered, coaching like a pro.

I squeezed when the buck froze and saw him collapse into the grass. Ross popped my back with an enthusiastic hug of congratulations, then we sat down and enjoyed the moment.

“Last night I went to sleep thinking about the time we hunted antelope together in Colorado,” Ross began. “I was six or seven, and that big buck we were after stopped way out on an open flat. You said it was too far for a shot.”

“Then those horses came over to see us and we just got up and walked toward that buck,” I added. “You hooked a finger through my belt loop, the horses fell in behind you, and that buck didn’t give us a second thought. We cut the distance until the shot was easy.”

“I still remember you telling me how the old-timers did that,” Ross added. “In fact, I remember it being my idea to give it a try.”

He was right, as always.

“Remember how happy we were when mom shot her big buck the following year on the same ranch? She dropped down with the bipod, stuck herself full of cactus and still managed to make a perfect shot.”

We remembered more about our past hunts while dressing and quartering the buck, then packed him to the truck. Back at the motel, we shared the morning’s story and laughed our way through the retellings with the rest of the crew.

During the drive home, I promised myself not to sell pronghorns short any longer. They offer one of North America’s finest sporting opportunities and hunting them is just plain fun! I won’t ignore them again.

This book is a collection of outdoor stories wrapped in the human condition. They were written with an eye toward honesty and cynicism. They will make you laugh out loud, and you will want to carry them with you wherever you go. If this book goes missing, it’s a sure thing that, when you do find it, it will be in the possession of a member of your household, regardless of their interest in casting a fly. The stories cover the gamut from a fishing trip to northern Canada to a little stream that was actually better than remembered, to how the baby boomers almost trampled a sport to death, to a solitary trek along railroad tracks during a cold, dark, and dreary February and many more. Shop Now

This book is a collection of outdoor stories wrapped in the human condition. They were written with an eye toward honesty and cynicism. They will make you laugh out loud, and you will want to carry them with you wherever you go. If this book goes missing, it’s a sure thing that, when you do find it, it will be in the possession of a member of your household, regardless of their interest in casting a fly. The stories cover the gamut from a fishing trip to northern Canada to a little stream that was actually better than remembered, to how the baby boomers almost trampled a sport to death, to a solitary trek along railroad tracks during a cold, dark, and dreary February and many more. Shop Now