We slipped through the night like three mottled wraiths, following blood and bone from the big wounded hog deep into the dense Florida swamp. The dogs were hot on his trail, and our hopes of finding him were high, here at the end of our first evening before beginning a quail hunt we’d been planning for months.

Oak and palmetto, gallberry, bluestem, and blackroot clung and clutched at us like fingers of doom. Rifles were useless in such blind, binding quarters, and we carried only our knives.

“If the dogs catch up to him they’ll grab him, and they won’t let go,” whispered my guide, Randy Ransom. “Then we’ll grab him ourselves and finish him.”

Remarkably, it actually seemed a quite reasonable plan at the time—though now as I sit here safe by the fire in my big leather chair, it all seems a rather daunting prospect.

But I was the one who had wounded this big feral hog with my rifle, and now I felt deeply that it was my responsibility to try and help dig him out.

A network of raised walkways connects Gilchrist’s elegantly furnished bungalows with Suwanee Lake’s Dining Lodge.

I was at the 27,000-acre Gilchrist Club just north of Trenton, Florida, with my longtime hunting partner Chuck Wechsler. We had initially come here to hunt bobwhite quail. But our host, General Manager Bob Edwards, had suggested we also take time for some of Gilchrist’s prolific wild hogs.

Chuck is a veteran hog killer of the first degree. But for my part, I had never gotten around to hunting them, and this sounded like an interesting opportunity. So, in addition to my bird guns, I had packed my trusty old lever-action .35-caliber Marlin, for it is the handiest and most trusted close-quarters rifle I own.

The morning following that first abortive attempt at hogs dawned cool and misty. Breakfast was a southern tour de force, and soon Chuck and I were following Randy Ransom and his son Randy Jr. into some of the most classic bobwhite quail habitat I had ever encountered. It was all new country for me.

Randy Ransom Sr., Gilchrist’s wildlife manager and head guide, is pure native Florida. He grew up running cattle in the Everglades and is as much at home on horseback as he is in a hunting truck or Jeep rigged for bird-shooting.

And he dearly loves his dogs.

Especially his black Lab, Daisy.

Now if I were ever asked why I love to hunt quail, my first answer would not be for the birds themselves. Nor would it be for the guns, though I find extreme satisfaction in viewing and holding and hunting with a fine shotgun.

Instead, it would be for the dogs.

I find no greater pleasure than hunting over fine bird dogs, be they pointers or setters, shorthairs or Brittanys, as they work the southern sedge for bobwhites, the stubble of the Midwest for pheasants, or the thick northern alders for grouse or woodcock. To watch a little high-spirited English cocker or a big black or yellow or chocolate Lab waiting tense at its master’s heel for the order to “put ’em up” is the epitome of love and mutual devotion.

And I have never seen such love and devotion between a man and a dog as I saw that first morning between Randy Senior and Daisy.

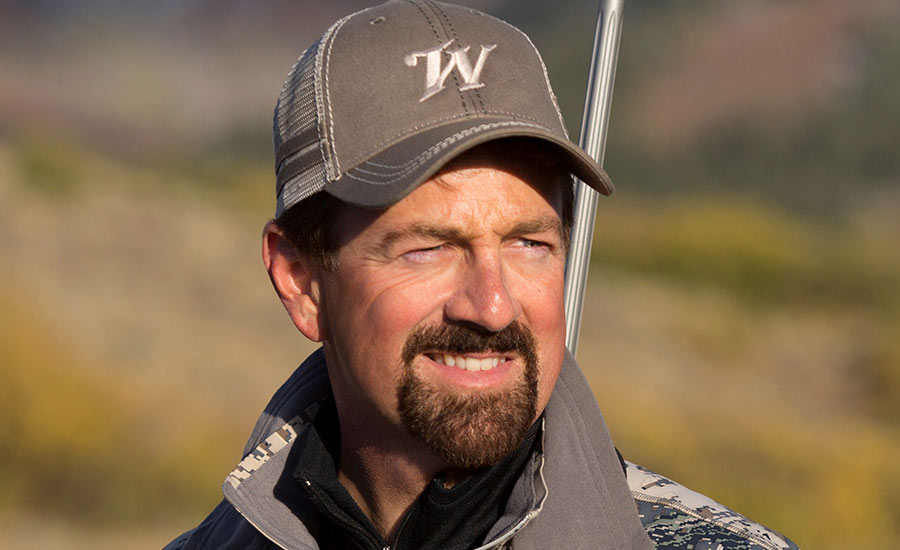

Randy Ransom Sr., wildlife manager and head guide, with Daisy, his devoted companion.

Daisy’s story had initially been one of failure—not so much on her part, but on the part of those who had failed to recognize her unique sensitivities or to realize her true potential.

How it all came about, I never got the whole story—except that by the time Senior came along, every dog man who had tried working her had pretty much given up on young Daisy. And her days afield seemed numbered.

“Hey, I’ll take her!” Senior declared emphatically once he learned her story and saw her frustration, and he took her home to live with him and his family. For six months she rested there, until the pressures of being a bird dog with too many handlers were a thing of the past.

He then began taking her with him in his truck and letting her run and play in the woods and fields, and she eventually became one of the finest dogs to ever sift the Southern breezes.

And now as we followed him and Daisy and an equally fine pair of English pointers named Molly and Belle through the sedge and palmettos and longleaf pines, I marveled at what one good man and a well-bred, well-trained bird dog could accomplish together.

Our first point came within minutes.

The interior of the lodge.

Randy hardly ever had to speak to his dogs. But when he did, he spoke gently.

“Molly, hunt close . . . come around Belle . . . Daisy, heel . . .”

And they did.

As soon as Chuck and I were in position, a barely perceptible glance from Randy told Daisy it was time

to roust the birds.

“Never wear sunglasses with your dogs,” Randy later explained. “That way, you can look them in the eye.”

The covey broke dead away, and Chuck dropped a double on the rise. Belle and Daisy were quickly back at Randy’s side with the birds, and when we looked up, Molly was again on point 40 yards ahead. Belle circled around to the left, and when she saw her brace mate locked up, she immediately froze on a backing point.

With our guns broken open, Chuck and I flanked the dogs as Randy and Daisy approached from the center, and when we signaled that we were locked and loaded, Randy sent Daisy in for the flush.

This time a bob and a hen rocketed from beneath a young palmetto, and we dropped both birds. For a few minutes we followed up the singles, then left them alone and continued through the pines and sedge in search of another full covey. We found them a couple hundred yards away along an old overgrown sand track.

This time it was Daisy who first began detecting scent far out to the left, while Molly and Belle worked along the right flank. I didn’t see Randy’s subtle signal to his pointers, but somehow they knew to swing around toward Daisy and pointed again.

The covey broke in all directions, with one bird tearing past my right shoulder as I swung on another. I missed it completely, but quickly picked up another bird out to the left and folded it with my back trigger and tightly choked left barrel.

And thus the morning went—and the afternoon as well. The habitat was classic and so was the dog work, and the quail hunting just got more and more intense with each new day.

Randy Sr. and the author wait for birds to flush.

We soon settled into a routine: Randy Sr. and Randy Jr. would pick me up at my private lodge each morning an hour before daylight and we’d be off in search of hogs with Sam and Yellow and Abe, the Ransoms’ big Partin curs. We’d meet Chuck with the bird dogs around 9 a.m. to hunt quail, take a long leisurely break for lunch, and hunt quail again until 4 p.m.

Then we’d switch dogs once more and head back into the thick stuff for hogs until dark—for I simply could not get the image of that first evening’s big wounded hog out of my head.

As I said, I had been the one who had wounded him, in the final feeble wisps of light before full darkness. And I’d felt it was my responsibility to go in with the Ransom boys to try and finish him off with our knives.

“This is completely your call,” I had told Senior. “If you guys would rather I stay out of your way, just say so . . . otherwise, I’m comin’ in with you.”

“Absolutely!” Senior had assured me. “We’re gonna need all the ears we can get. These hogs are tough and they’re smart—smarter than a dog or man when we’re in their territory. They can’t see worth a flip, but their noses and ears and tusks are razor sharp. I’ve seen ’em take far more lead than this and never slow down. You’re good to go.”

At first I followed Junior . . . or maybe it was Senior . . . honestly, I couldn’t tell for certain, for the opaque blackness and the density of the clinging brush drank in the glow from our flashlights, rendering them useless beyond a couple of feet. Then we all split up, and the night quickly absorbed the receding lights of my companions.

Orion’s Belt sat high in the black northern sky and was now my primary point of navigation as I moved forward alone, one slow and deliberate step at a time, ever deeper into the darkness toward the edge of the unseen swamp.

Finally, I stopped and stood and closed my eyes to listen, for eyes were nearly useless.

I could barely detect Sam and Yellow and Abe as they ranged back and forth somewhere out ahead. But there were no other sounds, except the thickened breeze and the rustle of the trees and my own steady breathing and the percussive whisper of blood pumping through my veins.

Then something sizeable suddenly erupted from the tangled brush scarcely ten yards below me.

I quickly turned, low and square to the sound, with my feet braced and my old elk knife held firmly in my leather-gloved hand. But instead of charging me, the big hog was charging away, leaving me surprisingly disappointed.

I called softly to my friends, who soon converged from left and right, and we quickly found where the hog had been waiting for us.

“He’s making for the water!” Junior exclaimed. And so did we. The thick vines clutched and clung at our legs and arms and shoulders, and the cat briars tore at my hands and sleeves as we tore after him.

At some point Yellow returned to us, her shoulder deeply gashed by the hog’s telling tusks. But we never caught up, never heard another sound from him that night, nor found any trace of him the next morning at daylight.

And that is something I will always regret.

For a week Chuck and I stayed at the Gilchrist Club, hunting hogs at first light, then heading off for quail during the day before returning to the thickets for hogs in the evenings. And the thread that tied it all together was Randy Ransom and his son, and especially the dogs they had so lovingly and expertly trained.

Cur or setter, pointer or Lab, I learned just what can be accomplished when you combine the finest men, the finest dogs and the finest habitat into one well-tuned experience.

The bird hunting was some of the most enthralling I have ever encountered. But surprisingly, a growing passion for hunting wild hogs continued to well up inside me, for after losing that big hog on the first night, the fire continued to smolder and build, until it became just as important to Senior and Junior that I get a hog as it was for me.

Randy Ransom Sr. and Randy Jr. pose with the author’s hog and his father’s old 336 Marlin.

We finally found them a half-hour after sunrise on our last morning, along an old canal near Bear Bay.

How Junior ever spotted them as we eased through the dense woods remains a mystery to this day.

But spot them he did.

They were a hundred yards or more away, atop a thick palmetto hammock. At first they were just a few random specs of cold, hard black in the warm shearing light of dawn, and it took me a moment to spot them for myself.

When we began moving on them, I fell in directly behind Junior to minimize our profile, carrying the old Marlin backward, low and in line with Junior and the hogs, its muzzle pointed straight behind us for safety. When we could advance no farther, I eased up beside Junior and raised my rifle to my shoulder.

There must have been a dozen hogs or more milling about in the thick palmettos, with one big boar out along the far edge of the herd. Then suddenly, an even larger hog appeared, stage left, moving into the crosshairs of my scope . . . but he, too, was mostly obscured by the dense ground cover.

Then a single black form stepped forward into a narrow opening between two big sweetgums, a perfectly proportioned meat sow, open and clear and quartering away. There were no other hogs in front of or behind her, and knowing that I may not get a better, more open shot than this, I slipped the 200-grain Hornady bullet into the back of her ribs. It angled forward through her chest with devastating effect and exited her opposite side at the base of her neck.

She dropped in her tracks.

By the time I racked another round into the chamber, the rest of the herd had disappeared. We were halfway up the hammock before we spotted her lying motionless in the leaves.

We shot a few obligatory photos and then dragged her out to the truck, and I do believe the Ransom men were even happier for me than I was for them. They had worked extremely hard to put me onto these hogs, and for that, I am forever grateful.

But the part I remember most is working through a dark Florida thicket a few nights earlier.

And how good that old elk knife felt in my hand.

Back in the quail fields, three-year-old Brooke strikes a stylish pose.

This fascinating anthology showcases 38 wonderful stories from those halcyon days when sporting gentlemen pursued the noble bobwhite quail with their favorite shotguns and their elegant canine companions.

This fascinating anthology showcases 38 wonderful stories from those halcyon days when sporting gentlemen pursued the noble bobwhite quail with their favorite shotguns and their elegant canine companions.

The 368-page book opens with compelling tales by the literary giants from quail hunting’s golden era, including Nash Buckingham, Robert Ruark, Havilah Babcock, Archibald Rutledge, and Horatio Bigelow.

The book’s second section presents reminiscences by sporting scribes of the modern era, among them Jack O’Connor, Gene Hill, Joseph Greenfield, Dave Henderson, and Mike Gaddis. The third section is comprised of unforgettable short stories on quail hunting and bird dogs by James Street, Bob Matthews, Dan O’Brien, and Caroline Gordon.

Will the sweet sound of whistling wings, the heart-stopping beauty of a sunset point, the timeless partnership of a man and a dog wise in the ways of wild birds ever return? Perhaps, but for now we can rejoice in the fact that we can, through the writings of some of the finest sporting scribes America has ever produced, experience those golden days vicariously. Buy Now