Invasive feral hogs provide delicious all-natural meat free of steroid injections. Best of all, they provide a hunting season that never ends.

The tracks of whitetails, turkeys and feral hogs crisscrossed and piled on each other, captured in the temporary cement of red clay that had not received rain in weeks. Mike and I had hunted turkeys that morning but entered the swamp road toting slug guns and looking for swine. A small pine stood to the left of the road, and a portion of the tree’s bark had been eroded away. The invasive beasts used it as a scratching post.

The road had been built through a cypress–tupelo swamp adjacent to the Savannah River. Mike had hunted pigs in that lowland for years and had adopted a still-hunter’s approach, which made good sense to me. We walked at an inchworm’s pace, looking, glassing and listening, certain we’d see hogs—evidence of their work gouged the ditches of the road, the road itself and any ground higher than the swamp soup.

The colors of spring remained hidden in the buds, which enabled us to see deep into the floodplain forest where the buttressed trunks of ancient trees held firm in the soft ground but bore hues similar to muddy pig. After 20 minutes we’d seen nothing but abundant sign of their invasive presence.

Ten minutes later Mike stopped and squinted. He heard something I didn’t, and entered the swamp to our right. I followed. We tiptoed over damp ground about 50 yards and stopped. Then I could hear it—a sounder of hogs issuing a chorus of satisfied, low-level snorts.

“Eating them makes me feel like I’m embracing their presence.”

We walked farther and whispered a plan of attack. Like the buffalo hunters of old, we aimed to take the biggest females first, figuring the subordinates would remain within shooting range as long as the big mamas died in their tracks. We could see four or five head, picked sows and began an ambush that lasted all of seven seconds.

The shots set off an eruption of pigs and flying mud and screaming confusion that offered only glimpses of hide among the giant cypress, and when the smoke settled, four hogs lay dead, several ran free, and two carrying wounds ran bellowing toward the river. We debated dragging the pork to the road.

“Let’s just leave them all here,” I said.

“They’re good eating,” Mike countered.

“But they don’t belong here. Eating them makes me feel like I’m embracing their presence…like it’s a good thing.”

“Getting rid of all these pigs won’t be easy, pal. Take the good where you can.”

Eight years later that pine tree to the left of the swamp road succumbed; the hogs wore it in two. That little tree and its eroded rings serve as microcosms of a feral pig’s relationship to the land—destruction on many levels.

The USDA estimates more than 5 million feral hogs are running wild in the US. According to researchers at Mississippi State University, the estimated price tag of feral-pig damage across the country totals more than $1.5 billion a year—the damage includes nesting cover for gallinaceous birds and actual nests, bedding and birthing cover for native ungulates and food of any kind that everything else eats. Hogs even make prey of turkey poults and whitetail fawns.

But take the good where you can.

Hog hunting has created a niche for itself among manufacturers of sporting equipment. Loads and scopes and lights and attractants designed specifically for pigs flood the market each year, and many such products help stores in rural areas keep their doors open.

Also, in and of themselves, feral hogs have a few things in their favor. First, they’re fun to hunt. Second, they can be hunted every day of the year. Finally, as my friend Mike said, they’re good eating, especially when served among hunting brethren gathered together.

In short, feral pigs are bad for forests, swamps, fields and native wildlife, but fun for hunters and valuable to anyone in need of meat. Further, it seems the bad news is also the good news: Their rate of proliferation and ever-expanding range means feral pigs are likely here to stay.

I’m not suggesting we go all European royalty here, but hunting and killing feral hogs could support a more passionate following.

Seems we need to take pig hunting more seriously. We could learn a thing or two from the Europeans.

Hunters in the old countries celebrate the boar hunt with music, fire and ceremony. They wear fine hunting clothes. They carry and shoot rifles crafted by old and respected manufacturers, and they tend to pile up the pigs.

I’m not suggesting we go all European royalty here, but hunting and killing feral hogs could support a more passionate following, something akin to the old-time deer-hunting clubs, where community members from various societal levels met at old shacks and ran dogs and spent mornings and afternoons hunting. Where young boys learned how grown men interact with each other, the land, dogs, and cooking accouterments. Try combining the social gatherings that accompany dove shoots with the fervor of deer, duck and turkey hunters.

Instead of simply hunting wild hogs during lazy afternoons of turkey seasons or taking shots at them from deer stands, build parties around them. Organize hunts that run the day and night. Invite your friends.

For sportsmen, feral pigs are something of a dream come true. Killing them is good for everything else in the wild—so killing a lot of them is even better. They provide all-natural meat free of steroid injections, and feral hog is one of the wild meats that doesn’t have to be wrapped in bacon to be palatable. Best of all, they provide a hunting season that never ends.

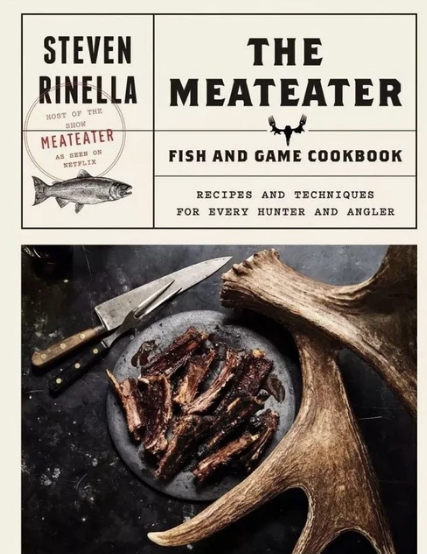

In this comprehensive volume, Steven Rinella gives step-by-step instructions on how to break down virtually every variety of North American fish and game in a way that is best for cooking, offers advice on which types of fish or game—and which cuts in particular—work best for various preparations, provides recipes and cooking tips from other renowned hunters and chiefs, and includes instructions for making basic stocks, sauces, marinades, pickles, and rubs that can work with a variety of wild game preparations. Readers will be delighted by Rinella’s personal stories, both of cooking and hunting, as well as his insights into turning the wild game he harvests into food. Shop Now From the host of the television series and podcast MeatEater, this long-awaited definitive guide to cooking features more than 100 new recipes for wild game, fish and waterfowl.

From the host of the television series and podcast MeatEater, this long-awaited definitive guide to cooking features more than 100 new recipes for wild game, fish and waterfowl.