We were standing three abreast when a cow charged through the dust.

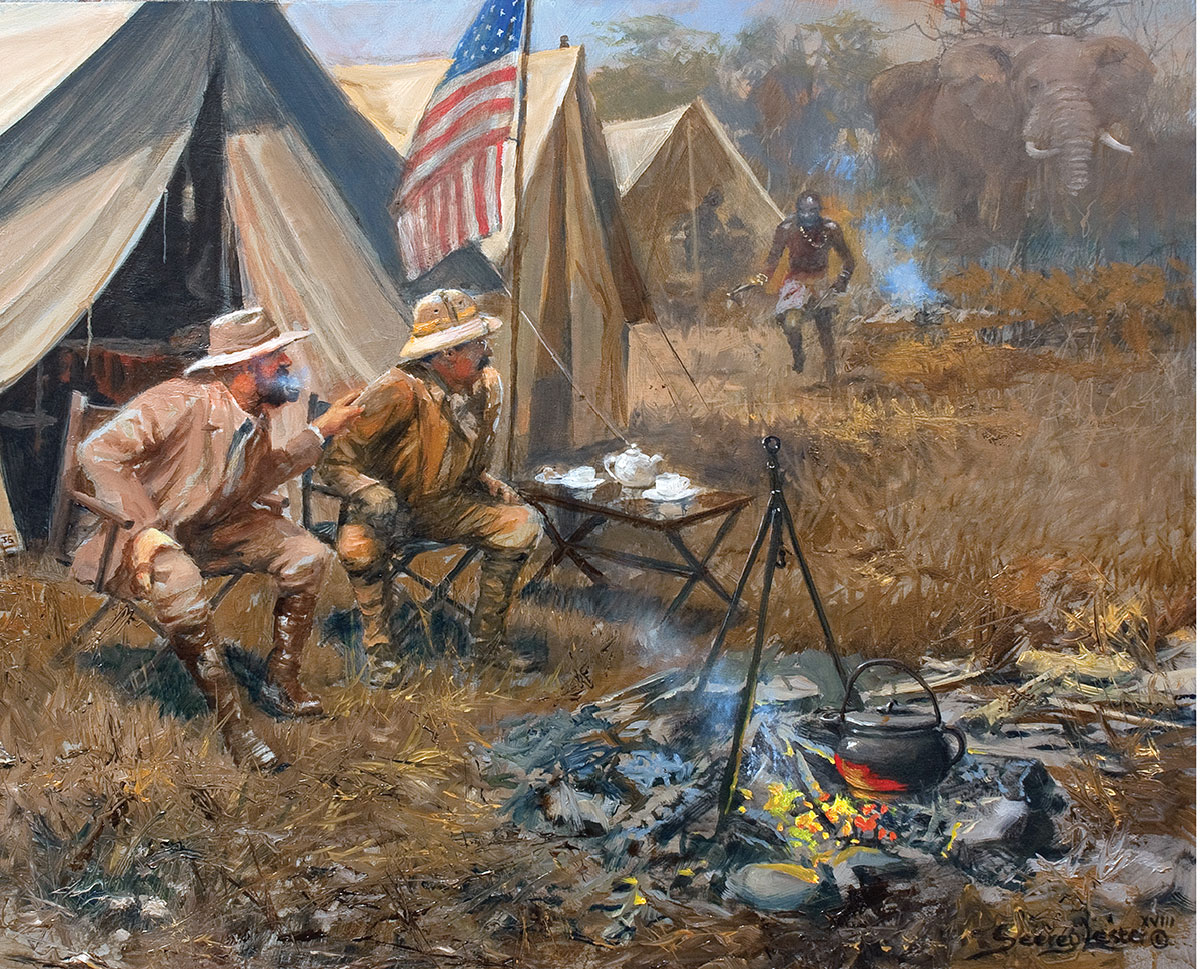

It was Rick Stoeckel’s second African hunt, as with most he had cut his teeth on plains game and couldn’t wait to return for something big. By the time our plane bounced down hard on the old military runway at Katima Mulilo in Namibia’s Caprivi Strip, he was running on adrenalin and wondering if his rifles had survived the landing. Our party of four formed up on the tarmac, then absent formal instruction, set out toward a block building that looked promising. We skirted an old Hind helicopter with massive rotor blades drooping in the sun like petals of a wilting daisy, her empty gun ports a reminder that political differences thereabouts had not always been settled with words.

It was Rick Stoeckel’s second African hunt, as with most he had cut his teeth on plains game and couldn’t wait to return for something big. By the time our plane bounced down hard on the old military runway at Katima Mulilo in Namibia’s Caprivi Strip, he was running on adrenalin and wondering if his rifles had survived the landing. Our party of four formed up on the tarmac, then absent formal instruction, set out toward a block building that looked promising. We skirted an old Hind helicopter with massive rotor blades drooping in the sun like petals of a wilting daisy, her empty gun ports a reminder that political differences thereabouts had not always been settled with words.

The shade inside was welcome, but there was too much Africa in the air so we passed through to a covered area, scattered packs across a picnic table and waited for professional hunter Jamy Traut. We didn’t have to wait long, and soon could hear the whine of a motor before his hunting truck leaned hard around a corner and rocked to a stop. He jumped out, smiling and waving, his cell phone pinched between a shoulder and his good ear. His arms cradled cold bottles of water for everyone.

This hunt would make an even dozen I had shared with Jamy, and it was wonderfully evident things had not changed. There simply is no more kind, thoughtful and friendly person on the face of the earth. Jamy Traut makes Mr. Rogers look like a criminal.

Some of the guys had met Jamy stateside at hunting shows earlier in the year, but I repeated introductions just in case. Adam Heggenstaller from NRA Publications and Skip Knowles with InterMedia Outdoors were writer-guests and came first, then Rick from Federal Cartridge. Another truck pulled up and soon all shook hands with Anton Esterhausen, one of the handful of professional hunters in Namibia who, like Jamy, is actively licensed for dangerous game.

By some miracle our luggage arrived and then managed to fit into the trucks. Soon we were roaring down a tar road and dodging western roan, Chinese construction crews and those ribby brown dogs that seem to define rural Africa. Camp itself was on an island surrounded by backwater from the Kwando River.

At the hippo-excavated launch we chain-ganged gear to a waiting boat, and minutes later were welcomed by the staff with a tray of cold drinks. Jamy had only recently taken over the camp and several remodeling projects were underway, but everything was ready enough and the waiting tents offered comforts far beyond expectation.

Not enough daylight remained to check zero, so we gathered in the raised dining lapa, took in the view and talked things over. As guests, Adam and Skip had first choice on what game they’d hunt. Predictably, Adam chose Cape buffalo. Skip, on his first safari and wanting to experience as many different opportunities as possible, spoke for the hippo/crocodile combination. Rick opted for an own-use elephant permit that allowed him to take an on-trophy bull or one with broken tusks. Given lesser odds, I would hunt leopard and maybe elephant if we stumbled across the tracks of a trophy bull. In addition, we would all have the opportunity to take a selection of plains game, including reedbuck, lechwe, black wildebeest and eland.

Daylight found us clustered near the launch and setting up a shooting bench. We each had a brace of rifles; a Kimber Model 8400 Caprivi in 416 Remington Magnum and another Kimber of appropriate caliber for plains game. With little fuss, we confirmed the big guns at 50 yards and the others at 100. Within an hour we were off to the conservancy offices, collected the required game scouts and started hunting.

Jamy took Adam and Skip to a riverine area stiff with plains game while Rick and I rode with Anton to look for elephant tracks. That we were in good hands was never in question.

Following an interesting and very active military service, Anton had worked for nearly 20 years as a game ranger in several of Namibia’s vast national parks. Between rangering and professional hunting, he’d been around elephants for more than half his life and had taken 70, mostly during control operations. Rick had never seen a wild elephant before, which in retrospect makes what we were about to experience even more incredible.

In addition to collecting trophy fees, the conservancy retains possession of meat taken by hunters and distributes it in the villages. Locals are highly motivated to see that hunters are successful, so it didn’t come as a surprise when the game scout reported an elephant herd had been raiding crops at night. We lined out to look for them and discovered their tracks in less than an hour. There was a bull in the herd, and his track was big enough to be promising.

Elephants often travel great distances after feeding and the tracks appeared to be several hours old. Anton and the game scout agreed it best to use what passed for a network of roads to grid the area, hoping to cut more tracks and determine if the herd had settled for the day inside the concession. We had not gone far when one of the guys up top spotted an elephant’s back rising above the brush and tapped on the roof so Anton would stop. Up we went to take a look, but thick cover blocked all detail.

Anton nodded toward the rifles, so we quietly loaded 400-grain solids and slipped into the brush to make a wide circle and gain the wind. Going was slow, everyone trying to avoid crunching the fallen leaves while staying clear of the wicked thorns. We also realized that the herd could be spread out and didn’t want to risk bumping one before getting a look at the bull.

Within minutes we’d gained the wind, closed on the animals and began to see their outlines. The first was a cow, then the bull came into focus just beyond. The scout took to a tree, and then climbed down to tell us the animals were grouped tightly together. We continued to circle and close the distance.

Soon we got something of a break, the cover thinning and more of the herd coming into view. A flash of ivory caught my eye, but in the binoculars it became the thin tusk of a cow. I was last in line and could not see the bull when Anton stopped and pointed.

Knowing we were close, I held position while Rick crept forward, listened to Anton’s whispers and then looked through his binoculars for a very long time. They finally motioned me up and we continued, clustering together and moving in until the herd was just 40 yards away.

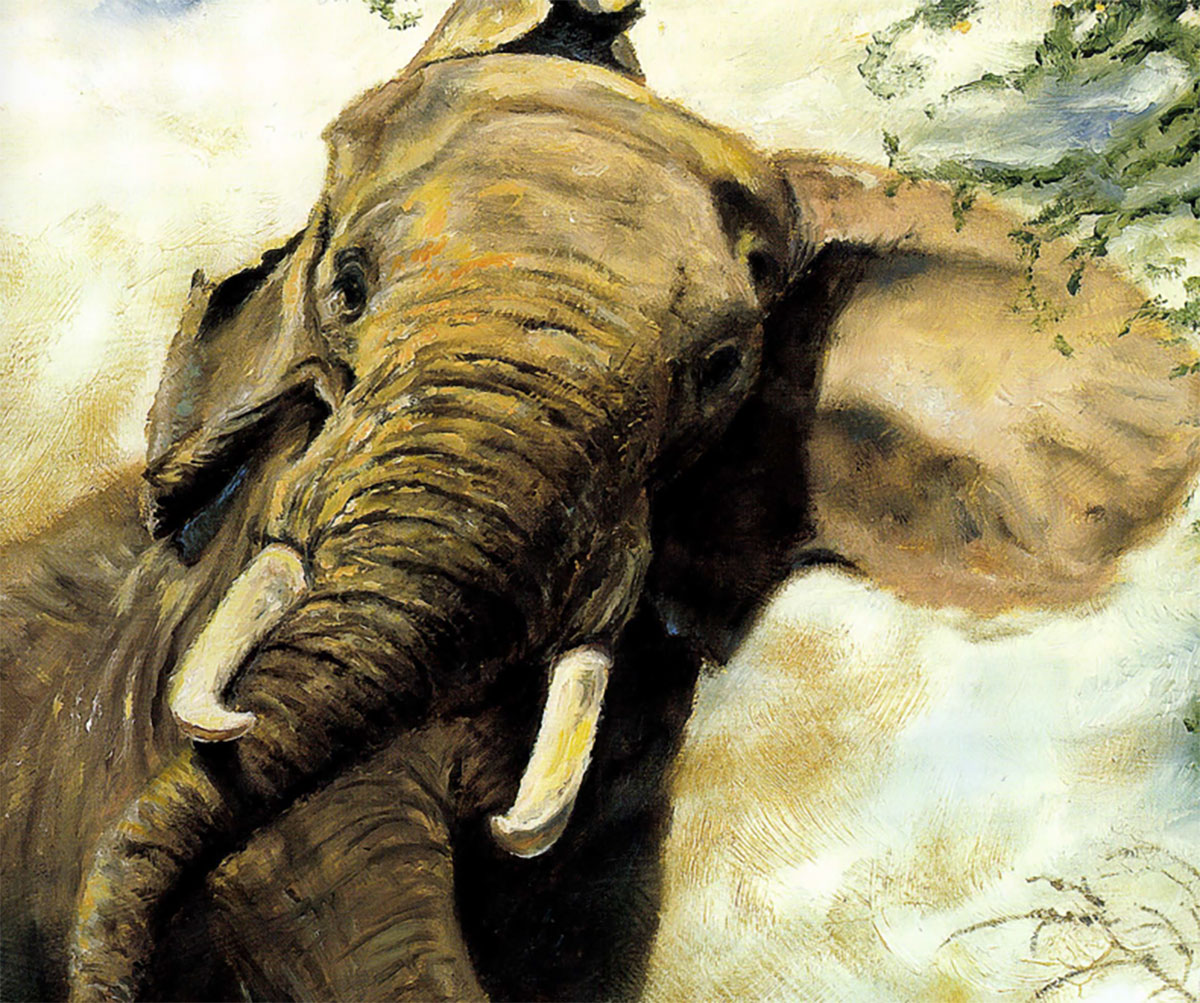

Anton and the game scout studied the bull with great care. Now broadside and clear, he had well-matched tusks and a giant head, which is the hallmark of older Caprivi bulls. His backline towered above the others. The bull finally turned his head enough so I could get a good look, and I quickly assumed he was too big to be taken on Rick’s own-use permit. I think Anton was on the same page, and he was even more surprised than I was to hear the game scout give Rick the green light.

Anton moved Rick forward a few steps to a tree that offered a proper rest, then carefully explained how to make aside brain shot. First through binoculars and then his scope, Rick traced the line between the ear hole and eye, settling the reticle on the spot Anton indicated.

The shot could not have been more perfect, the bull folding stem first as the rest of the herd bolted past him through a rising cloud of dust.

I quickly followed Anton around the tree to gain a better vantage while Rick threaded his rifle from between the branches and ducked around the other side.

We were standing three abreast when a cow charged through the dust. Whether she had circled back from the herd or had just stopped and waited to get her bearings we’ll never know, but she came on hard. I followed Anton’s lead, yelling and waving so she would change direction.

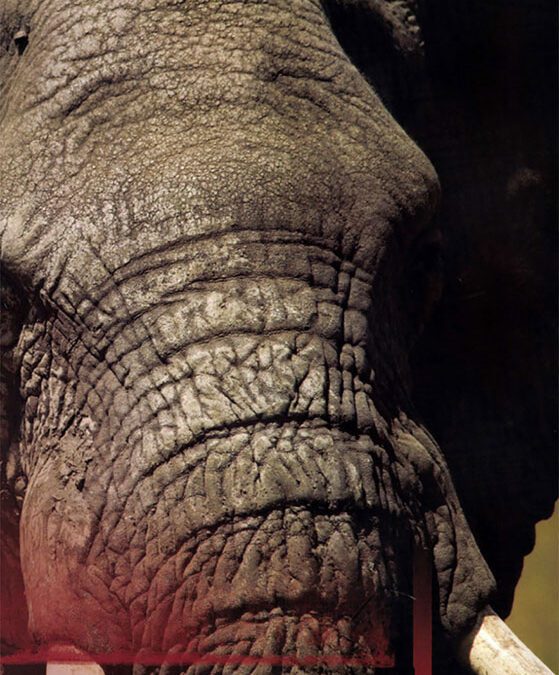

The instant she had us pinpointed, everything changed for the worse. She laid back her ears, lowered her head and tucked her trunk into her chest. Her strides lengthened and her pace quickened. Even her eyes seemed to narrow as she let out a rumbling squeal.

Instead of rounding the only tree between us, she burst right through it, scattering branches and showering splinters of bark into the African air. She was no more than 20 yards away when we threw up rifles.

I kept both eyes open, as much as to keep back of Anton as for fast shooting, and locked down on a spot between and slightly above her eyes. Rick was just to my right and, I actively hoped, doing the same thing.

The first move was Anton’s to make, and his shot broke when her forehead was 18 feet away. I followed at the report and a second white-rimmed spot appeared on her forehead three fingers above the first. I whipped the bolt and hit her again in the side of the head as she swung around and then crashed down, facing in the opposite direction. Rick had joined the fight at nearly the same instant, his bullet raking downward through the top of her skull.

From start to finish the charge took less than ten seconds and was the most thrilling experience of my life. Someone softly muttered ‘Wow!” through the silence. It might have been me.

We covered her together, reloading…in turn, waiting to see if she was down for good or that another member of the herd wasn’t about to try the same thing. The game scout soon joined us — I’m not sure from where — then we carefully checked both elephants to confirm they were dead.

The others from the truck busted through the brush a few minutes later and prompted the telling of the story several times, and within two hours people from the nearby villages began to arrive. They started fires and then sharpened knives and axes, waiting for the ivory to be removed so their work could begin.

We returned the next day and found nothing more than the largest bones and a few panels of skin. For the rest of the hunt we could not drive down a road without receiving waves of appreciation.

Skip was next to score. As it was with Hick’s elephant, locals reported a bull hippopotamus and we set out to find him the next morning — crossing open water where a big crocodile had recently taken a villager — in a hand-carved canoe with maybe three inches of freeboard. The elephant charge had nothing on this, so far as I was concerned. It took a long time to locate the hippo and then gain position, but Skip’s first shot on African game could not have been better and the locals were soon helping him drag the bull to shore. Anton removed a backstrap before declaring the butcher shop open for business. We ate those steaks the following night. They were fantastic.

Due to high water conditions near the main camp, Jamy had made arrangements for Adam to hunt buffalo in another of his concessions some distance east on the Chobe River. Rick and Skip joined Adam for the hip downstream on a fishing boat.

I remained with Jamy, searching for a big elephant track and checking leopard baits that had been placed by the camp staff. What we found could not have been much better. Two of the zebra baits had been hit and one was absolutely destroyed — bones cracked and binding wires twisted and broken by a big tom. Broad tracks pressed deep into the sand confirmed this was the one we wanted.

We returned with a crew the following day, building a blind 60 yards from the bait tree. Jamy supervised the operation while a fresh hunk of zebra was wired tightly to the underside of a limb.

I took some bearings through my scope and cleared a shooting lane, then returned to the tree to marvel at the claw marks from the night before. About that same time and far to the east, Anton and Adam completed a perfect stalk on a large herd of buffalo, waited for an attending bull to stand and took him clean. We held dinner for them that night and were happy to have everyone together again.

Just about the worst thing that can happen on a leopard hunt — other than wounding a cat and what might follow is running out of bait. If a leopard cleans up a bait, he generally will not return, and that’s the situation we faced the following afternoon. We had parked nearly a mile from the blind and snuck in without words. I crawled in first and was surprised to hear Jamy whisper, “Oh, no!” as I was getting set. Jamy is not given to strong language, so his simple words made my heart sink.

“The bait is finished,” he announced, cupped hands pressed to my ear. I zoomed the scope and checked. There was nothing left but bone, so bare that a fly would go hungry.

I thought about it for a long time and must admit that I didn’t hold much hope for the evening. Some people are lucky with big cats. I’m not, but this was the only game going and we had no other option than to see it through. Remembering there had been two more leopards feeding on this same bait — a female and a young tom by their tracks — I tried to convince myself they had come late in the night and finished things up. None the wiser, the big one would come back.

I quietly presented my theory to Jamy. He agreed that it was possible, but I suspect only out of courtesy. Later that evening he suggested that I might be blessed with the gift of foresight.

My eyes often become very dry in the Africa desert. Even though I use eyedrops frequently, there are days when the strain causes my vision to blur. This was one of those days. The only thing that works is to keep them tightly closed for a long time. Then once opened, I have a few seconds of clear vision before things get blurry again.

Worry over that and anticipation of the big leopards return had my guts tied in a knot, so when Jamy whispered, “He’s at the tree,” a jolt of adrenaline hit me hard. My vision cleared long enough to watch the big tom leap into the first fork.

“Take him!” Jamy hissed, no doubt expecting the cat to quit the tree as soon as he discovered his dinner plans had been ruined.

The reticle went out of focus before I could squeeze, which of course did nothing for the hyperventilation I was trying to control. Then the big tom curled himself behind the limb where the bait was hung. All I could see, when I could see, was a paw and his dangling tail.

He remained there for about five minutes — we know because all of it was captured on video. My breathing returned to more or less normal and the reticle eventually came back in focus.

Finally the cat stood, paused and turned to jump down.

“Take him now,” Jamy said unsuccessfully, but the reticle was clear and the slack came out of the trigger. My bullet parted the rosette marking the intersection of the leopard’s neck and shoulder.

The big cat stiffened, then tipped out of the tree with his feet in the air. Recoil took him out of the scope but I’d heard the bullet’s whack and, even better, a wonderful thump when he hit the ground.

Jamy slapped my back hard enough to make me cry, but my eyes needed the lubrication, so I took it as a blessing.

We backed out of the blind, checked chambers and started toward the tree, and didn’t have to go far before seeing the leopard stretched out in the sand. The truck arrived just then and we managed a few photos before the sun even hit the horizon.

“How many leopards in full daylight does this make for you?” I asked Jamy.

“This makes 12, I think, that had the sun on them at the shot,” he replied.

We spent the next week hunting plains game and looking for the right elephant track. Anton and I followed several bulls, got chased for our trouble and even closed with what we thought might be the one. He was, almost, so I passed. The others did well on plains game, and we ended the hunt with several big kudu from Jamy’s Panorama property far to the south.

We spent the next week hunting plains game and looking for the right elephant track. Anton and I followed several bulls, got chased for our trouble and even closed with what we thought might be the one. He was, almost, so I passed. The others did well on plains game, and we ended the hunt with several big kudu from Jamy’s Panorama property far to the south.

I returned home to a message from Jamy. He thought I might want to know that a huge elephant track had just been found entering the concession. Could I return? Yes — absolutely yes came the answer — but not right away. Someone else could have the opportunity, but I doubted it would begin to match what Rick, Anton and I had experienced.

Over the past three decades Sporting Classics has published more than 100 articles and columns on sport and wildlife conservation in Africa. This anthology, which commemorates the magazine’s 30th anniversary, features the best of those stories. Many talented, dedicated people made this book possible, particularly the authors who eagerly shared their stories. Buy Now

Over the past three decades Sporting Classics has published more than 100 articles and columns on sport and wildlife conservation in Africa. This anthology, which commemorates the magazine’s 30th anniversary, features the best of those stories. Many talented, dedicated people made this book possible, particularly the authors who eagerly shared their stories. Buy Now