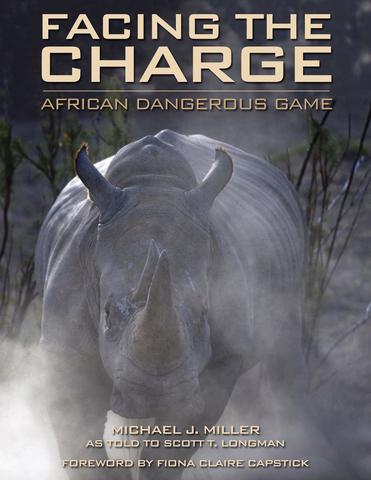

An excerpt from Facing the Charge, a safari book featuring true adrenaline-fueled tales of big-game hunting.

We’d launched just like we had for the prior six days, moving at first light as quickly as the Bushmen could track. For the first six days, we had been taking breaks every hour or so, to sit down, loosen up, have a snack, have a smoke. Not today. We stayed on it and kept pushing, keeping up the maximum pace that following the spoor would allow.

By lunchtime we were all knackered. I had some idea how the lion felt: I was tired, hungry, thirsty, and discouraged. We stopped, and I waved my PH, Lew, up with the trucks.

The Bushmen followed the lion’s spoor out of the immediate area and marked the last spot with a rock before coming back to rest in the lee of a kopje. Talking quietly between them, they moved up the rock and pulled out newspaper cigarettes.

Two of the staff were pulling coolers out of the truck. I’d have traded my teeth for a good eland sandwich, a beer, and a nap.

The vehicles were off to my right. The kopje with the Bushmen on it was maybe 20 yards straight ahead of us. Dad was standing between me and the kopje, maybe five yards in front of me. I had not yet put down the .375 Van Horn for lunch.

The rods in the human eye account for our best ability to detect motion and for our peripheral vision. They occur in the greatest concentration about 30 degrees to either side of central vision. On pure, magnificent accident, that field of vision in my right eye happened to be covering an area about 50 yards to the right of the kopje.

Oh, thank heaven.

It was a flash, a tan blur, but I knew instantly.

It was like slamming closed an entire panel full of high-voltage circuit breakers, an explosive surge down my arms and into my throat. I did not yell “lion,” nor did I yell “Dad.” I have no independent memory of what I bellowed, but they told me later.

It was: “HE’S COMING FOR YOU!”

Muzzle of my Van Horn coming down and stock coming up and a round already chambered.

The safety taking itself off.

The flashing instant of acquisition.

Swinging through like wingshooting.

Boom!

Instantly cycling, back on him.

Momentum carried the massive brute to a sliding, dusty stop three yards from Dad’s left boot. I rushed up and put an insurance shot through its head and cycled hard enough that the brass ended up seven paces away. Then I took in a Hindenburg-sized lungful of air.

As Lew and the staff rushed up, I got my first good look at our quarry. He was even more than what my glimpses had suggested: immense head and shoulders, peculiar light tan color perfect for the environment, and a big, full, shaggy black mane. The giant neck showed that the first shot I’d fired had gone just exactly where I’d aimed, spining him, which explained the instant pileup.

Lew didn’t say anything. The implications of each step of it all settled in. He clapped me on the shoulder.

The author and his father moments after they were nearly separated forever by this Kalahari lion.

My father, United States Army Master Sergeant Milo Milton Miller, Guadalcanal veteran, looked at me, his face expressionless. He had not moved. He looked at the lion three yards to his left. Then he looked back at me, breaking into a long, low smile. He’d completely adopted Lew’s philosophy of uttering some droll remark right after a big, hairy adventure. It was so perfect and so unexpected and so magnificent under the circumstances that I burst out laughing, an uncontrollable, relief-dumping, joy-filled convulsion that chain-reacted among the group.

“Listen,” Dad said, “I don’t mind you shooting my lion. But I’d have gotten him with or without your help.”

In addition to adrenaline-fueled tales of big-game hunting, Facing the Charge details how death was a constant companion on safari in the form of terrorists, quicksand, malaria and witchcraft, among other threats. It also analyzes how ivory traffickers have devastated the elephant population, examines the everyday hardships of life in Africa, and pays tribute to the men and women who have made Africa home. Shop Now

In addition to adrenaline-fueled tales of big-game hunting, Facing the Charge details how death was a constant companion on safari in the form of terrorists, quicksand, malaria and witchcraft, among other threats. It also analyzes how ivory traffickers have devastated the elephant population, examines the everyday hardships of life in Africa, and pays tribute to the men and women who have made Africa home. Shop Now