The most rarefied air on Earth is the painfully thin atmosphere between you and the malignant stare of a wounded Cape buffalo. The tiny bit of oxygen on the top of Mt. Everest must seem like molasses by comparison. You are connected in a wild, primordial way, as he peers savagely into your eyes, into your brain, into your soul. He’s obviously having a bad day. You caused it and now he intends to return the favor.

As the source of his torment, you are but a puny bit of rubbish to be quickly and easily gored, stomped and otherwise ground into the hot African mud. The old bull, solitary by nature and belligerent by evolution, at first only considered your intrusion into his world a nuisance, an aggravation. But now you’ve shot him and really pissed him off. He’s waited for you, hurt, angry and vindictive. At your very sight he’s decided you’re history.

As the source of his torment, you are but a puny bit of rubbish to be quickly and easily gored, stomped and otherwise ground into the hot African mud. The old bull, solitary by nature and belligerent by evolution, at first only considered your intrusion into his world a nuisance, an aggravation. But now you’ve shot him and really pissed him off. He’s waited for you, hurt, angry and vindictive. At your very sight he’s decided you’re history.

They say that fear is the greatest motivator — more demanding than hunger, more insistent than greed and more compelling than any sexual drive. Extreme fear — sweating, teeth-clenching, bile-in-your-throat fear — takes hold of your entire being and directs every movement and thought. Nothing else matters when you are walking the ragged edge. It doesn’t matter if you’re scaling the sheer walls of an ice-encrusted mountain, driving a race car at more than 200 miles-per-hour or stalking a mortally wounded dangerous game animal — if you do everything just right, you get to live. If you don ‘t — you don ‘t.

Being afraid of something that can kill you, that can end your life in the space of a few seconds, isn’t a sign of weakness. Rather, it’s a sign of intelligence. Yet the fact that you have put yourself in such a dangerous situation to begin with, where your very existence is in question, that’s when you begin to ask yourself how clever you really are.

The author’s hunting party scans the Okavango for

herds of buffalo.

I had been having running conversations, arguments really, with myself for almost an hour. The longest, most exciting, most frightening hour of my life. In my youth, I had foolishly driven a car with the speedometer pegged past a 120 with death only a blown tire away; as an adult, I fished in a boat much too small for twelve-foot seas that pounded us for hours. I even survived an encounter with a tight-lipped and totally humorless tax auditor. But nothing prepared me for this.

Step by step, heel first then toe, placed softly through the thorn brush and scrub palm, careful to make as little noise as possible, we inched through the Botswana bush looking for the infrequent drops of blood. At first, I thought I had missed the difficult quartering-away shot, with my iron-Sighted .470 Nitro Express double rifle. After fifty yards of following the bowl-sized footprints churned into the soft dirt, I really began to hope I had missed. Neither Johan Calitz, my PH or I wanted a wounded buff on our hands. But then, there it was, the ultimate damning evidence – a single drop of bright red blood turning dark in the dusty soil.

Thirty yards later, the trackers found another spot of blood. Many careful footsteps farther, another. That they were so few and far between probably meant I had shot the buffalo high, perhaps only in one lung, missing the shoulders. Ultimately fatal but immediately debilitating it wasn’t. I knew that it’s a cardinal sin to pull the trigger on a Cape buffalo unless you’re absolutely sure of a killing shot. But in the excitement of the moment and at Johan’s urging, shoot was what I had done.

Yet the PH seemed cool and confident. With every step, every intense, listening and searching pause, Johan demonstrated that he is one of the finest hunters I’ve ever seen. While I was reassured at his presence and knowledge, with each progressing step I cursed under my breath for having started this deadly game — that we now had to finish — one way of the other.

More than three-quarters of a mile and an hour later, studying yet another dime-sized drop of blood, it seemed to me that the spoor was becoming less frequent and smaller — not good. Twice we had heard the bull crash through the thick brush ahead, our pulses racing, not knowing if the unseen freight train was bent on escape or barreling toward us to burst into sight, snot-slinging and fiery-eyed, scant yards away. Each time, when the buffalo ran away from us rather than coming in a full-bore charge, Johan, my pal Butch Searcy and I looked at each other with great relief.

After every close encounter it hit me like a thorn bush limb across the face: there is at least some possibility, maybe a good possibility — that I might die today.

What am I doing this for? This really isn’t so smart is it? I could be at home right now, safe with my family, perhaps tailgating at a college football game or having a quiet dinner with friends? Is this something I really wanted to do? If something very bad happened, I could just imagine what my long-suffering and patient wife, now a most unhappy widow, would say to our children, relatives and friends about her crazy husband. “He didn’t tell me it would be that dangerous.” (I didn’t.) “If I had known he was going to do something this stupid, I either wouldn’t have let him go or at least bought more life insurance on him.”

But then, standing there in the sweltering African sun, with a rifle in my hand and a wounded Cape buffalo waiting for us somewhere in the long grass, it was a wee bit late to ask if this was something I really wanted to do. Yes, I wanted to do this. I have always wanted to do this. As it unfolded, this was an incredible hunt, an experience to be remembered, to be told and retold, to be savored for the rest of my life. I just hoped that my life would last longer than the next few minutes.

Cape buffalo may be the most celebrated animals in Botswana’s Okavango Delta. They are sometimes found in herds numbering in the hundreds to as many as a thousand animals moving across the land in a great mass of hulking black forms and swirling red dust.

Cape buffalo may be the most celebrated animals in Botswana’s Okavango Delta. They are sometimes found in herds numbering in the hundreds to as many as a thousand animals moving across the land in a great mass of hulking black forms and swirling red dust.

We mostly encountered small bachelor herds, qutali to our native trackers, grazing on the sweet grasses of the islands or shoulder deep in the marshes. Twelve-years or older, battered and battle-worn, these bulls are usually the ones with the most obstinate and dangerous attitudes. They seem to be mad most of the time.

Created by a river of the Same name that carves a verdant path through the Kalarari Desert, the Okavango is an environmental treasure with papyrus and grass-lined waterways meandering around game-rich islands. The sheer numbers of wading birds, waterfowl, birds of prey and other wildlife erupting from the tall grass and feeding on the islands are almost unbelievable.

Hippos live in the deeper holes of the channels, and we would occasionally graze their backs as we returned to camp in the evening. Nile crocodiles a dozen-feet-Iong slunk out of sight into the lily pads and reeds at our approach. Herds of red lechwe, brawny, lyre-homed antelope that dine on succulent marsh plants, splashed away from our boat, the handsome rams’ horns held back along their withers, their splayed feet sending up geysers of water.

Stately giraffes would glide through the forests like gigantic rocking horses, their heads towering above the tallest trees. Zebra, warthog, kudu, impala, blue wildebeest, reedbuck and tessebe all flourish in the Delta. Vervet monkeys leap through the trees with great abandon and budda-shaped baboons sit arrogantly on the tops of anthills, only to turn tail and run when pressed too closely.

With its large prey populations, leopards are numerous throughout the Delta. On a still night you can hear their sawing coughs as they make their nightly rounds along the river. Hyenas, those ugly, skulking scavengers that are so much larger than you first imagined, whoop and cry on their evening hunts. Sometimes, in the middle of the night, they edge so close to camp that it raises the hair on your neck. The screened fly of your tent seems flimsy protection from the carnivorous creatures of the night, and you always make sure a rifle is within arm’s length. But all this adds immeasurably to the wonder of Africa. After you experience it, you wouldn’t have it any other way.

Botswana is also famous for its magnificent, long-maned lions. We enjoyed the incredible luck of an up-close encounter with a group of five young males, probably four-year-old brothers, who let our Land Cruiser approach to within 10 yards as they lay relaxing, their tawny coats blending perfectly into the yellow grass.

The big cats, though still immature, were all nearly four-hundred pounds, and their state of satiated indifference said they had obviously just killed and eaten something large. They were nervous to be sure, but not nearly as much as we were. (We had discovered the skull of a old buffalo bull, a recent kill less than a half-mile away.)

A lion stalks away after being disturbed.

Four of the five watched us mostly with sleepy-eyed suspicion. But one, larger, more heavily muscled and with a longer mane, never took his eyes off us. While his siblings dozed, he slunk away, his pinned-back ears and twitching tail a clear warning that we had violated his comfort zone. In a year or two, when the time comes for him to fight his own brothers for leadership of a pride, our money would be on him.

There is absolutely nothing benevolent in the face of a lion. They glare at you with those penetrating yellow eyes with one of only two different countenances, either: “Get the hell away from me.” or “If I can catch you, I’m going to eat you.” To a lion, you’re food. For many hunters, because of man’s basic, ancient fear of being eaten alive, they are the most intimidating of Africa’s dangerous Big Five. At least Cape buffalo and elephants won’t turn you into dinner.

Another step forward and the clear Delta water swirled around our thighs like a tepid, snaky blanket. A few yards more and we would be in it up to our waist, severely restricting any inclination we might have to run. Four feet above our heads, the thick, wind-blown marsh grasses enclosed us like a waving green shroud. From here on out, because two people could stalk more quietly than three, Butch would wait at the water’s edge.

Johan turned and motioned for me to come up beside him. Shoulder to shoulder we once again checked the safeties of our rifles. In a whisper that I will never forget, Johan said, “The bull has gone as far as he’s going. The river is only two-hundred yards away. He’s going to make a stand in the water. When he sees us — he will come.”

“He will come.” Those words hammered home the reality of what I had truly hoped wouldn’t happen — that we were facing the possibility of a close-quarters, kill-or-be-killed charge from one of the most dangerous animals on Earth.

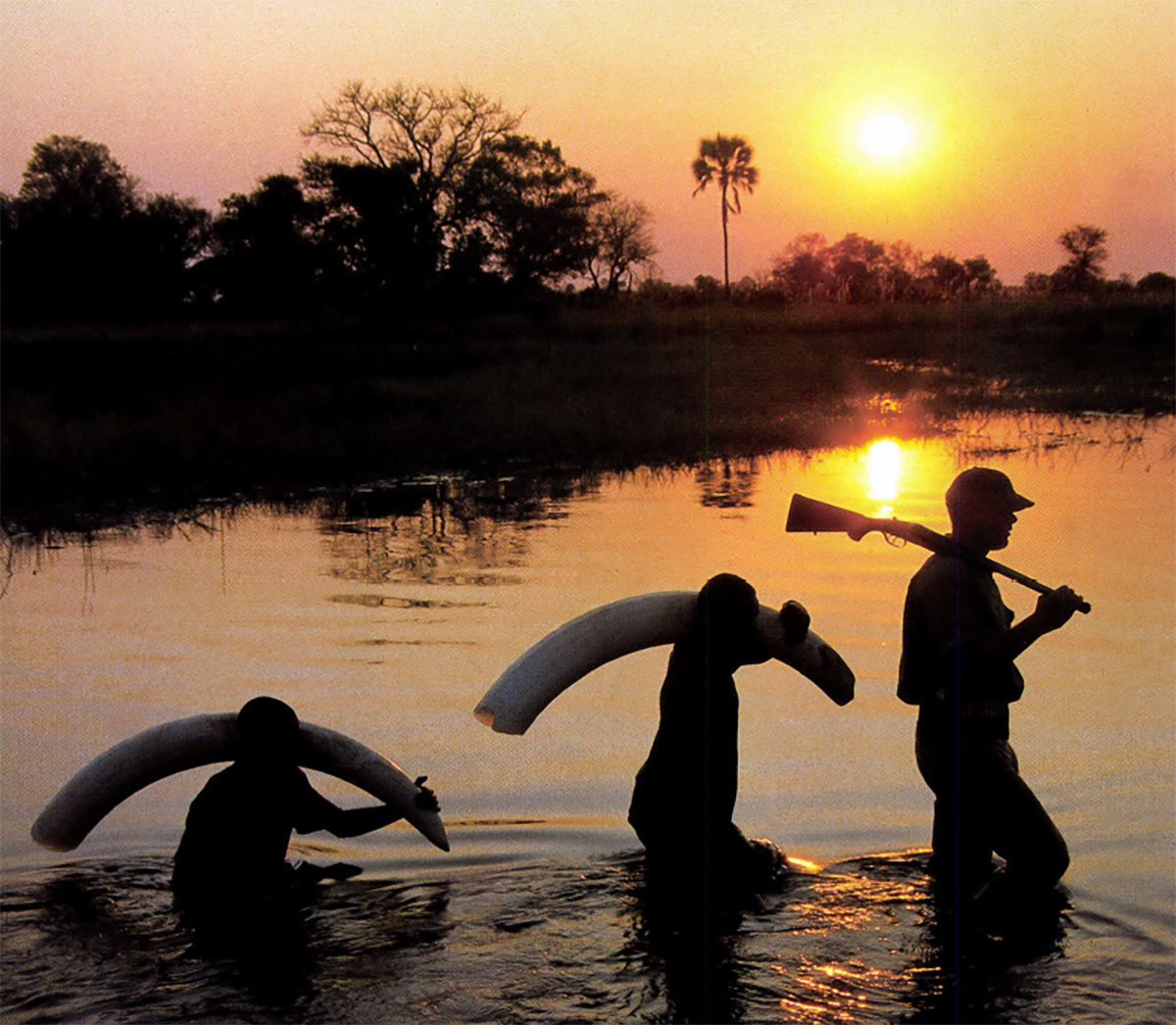

The trackers pole a traditional

mekoro dugout canoe loaded with trophies.

Cape buffalo just don’t understand. Sometimes, even when you have shot them in the vitals with a huge bullet from a cartridge the size of a cigar, they don’t get it. They seem almost unkillable, their oversized adrenal gland working overtime to defy basic biology. Pounded repeatedly with big bore rifles, they still retain their feet, their sheer force of life pushing them to seek vengeance on what has hurt them. When buffs are supposed to be dead, they ain’t. And even when you approach one thinking that it’s all over, that they are down and out, never, ever, let your guard down. Veteran PHs (old PHs, like old airplanes that have stood the test of time are good PHs) will tell you, “It’s the dead ones that will kill you.”

“Death by buffalo” can occur in one of several different and spectacularly eviscerating ways. Those thoughts swirled through my mind like a swarm of stinging bees. With each daunting image, my hands gripped the big rifle even more tightly.

We were reenacting a millenniums-old drama that has been a everyday occurrence on the African continent since humans and wild beasts first encountered each other. Mankind first sprang from Africa, in the beginning naked and nearly defenseless, but soon using his growing intellect to become the dominating force in the eat-or-be-eaten game of survival. And it’s still so today, all across this wild paradise, as it was eons ago, where the strongest or most intelligent beings force others to evolve and adapt or eventually be erased from the planet.

The wading bird demands that the fish swim faster or develop better camouflage. The lion demands that the antelope remain a step quicker. The buffalo demands that the hunter, if he is to take part in this high stakes game, be accurate and deadly or suffer the consequences of where two-thousand pounds of cunning and sheer tenacity can turn the tables in a second.

As we entered the water, and I knew a solution to our dilemma was imminent, I began to feel a new sensation, a strange, almost unreal calmness. I don’t know if it had very much to do with bravery; it was more of a trust, foolish or not, that everything would be all right. At that precise moment, my two most valuable friends in the world were the man on my right and the big rifle in my hands. I trusted that both would perform well when I needed them.

The swirling wind evaporated the sweat on the back of my neck, and I knew the wounded bull would likely smell us long before we saw him. We inched along silently on the trail that the animal had bull-dozed through the dense marsh, mud sucking at our feet with each difficult step, the droning of insects in the long grass above us mocking our advance.

Then there he was, only thirty-five yards away. The bull was magnificent, more than forty-inches wide, with heavy, deep hooks that curved down, up and back, a massive boss and huge body, easily the largest we had seen all week. He was big, black and terrible in his rage, in his intentions.

As he gathered to charge, the rifle bucked in my hands almost of its own accord, its thunderous report sending cattle egrets squawking away for hundreds of yards. The buffalo fell ponderously among the reeds, sending out a wake of water that lapped at our legs. Everything, the entire area, the entire world, was quiet except for our breathing. Even the insects were suddenly mute.

Was he dead?

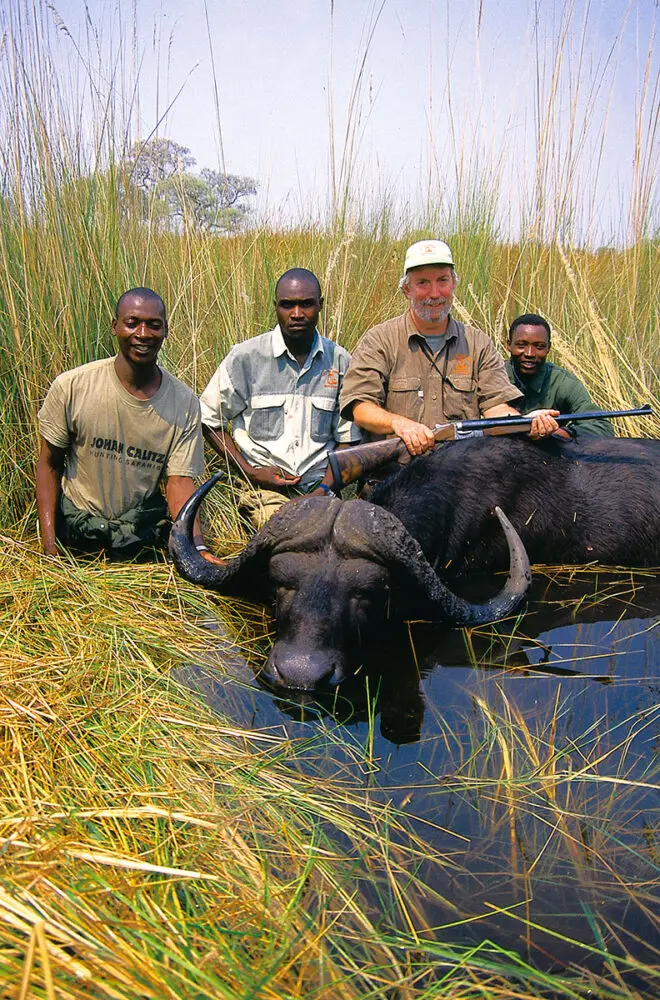

Tswana trackers Olie, Active and Dan

with the author and his hard-won buffalo.

The huge bull made his last stand in

dense marsh grass and waist-deep water.

“Come, we must finish it, ” Johan urged, taking hold of my shoulder. Praying that it was indeed finished, I held the rifle at ready as we cautiously waded within a few yards of the fallen bull. He lay on his side with his back to us, horns hooked in the matted grass. Dead.

“Give him another one in the spine to be sure,” Johan ordered.

As the gold bead of the front sight settled on its target, suddenly our “dead” buffalo began to gather his feet to get up! Heavy horns ripped the grass as he turned his head toward us. Johan and I both involuntarily jumped back a couple of feet, pulses pounding in our heads.

“Shoot!” he yelled, but the trigger of my rifle was already halfway home and fire and bullet belched from the big gun once again. The buffalo ceased any movement. Johan and I looked at each other, but a deafening silence strangled any chance we might have had to speak. It was finally over.

From the master of adventure behind the classic Death in the Long Grass, former big-game hunter Peter Hathaway Capstick now turns from his own exploits to those of some of the greatest hunters of the past with Death in the Silent Places.

From the master of adventure behind the classic Death in the Long Grass, former big-game hunter Peter Hathaway Capstick now turns from his own exploits to those of some of the greatest hunters of the past with Death in the Silent Places.

With his characteristic color and flair, Capstick recalls the extraordinary careers of men like Colonel J.H. Patterson and Colonel Jim Corbett, who stalked legendary man-eaters through the silent darkness on opposite sides of the world; men like Karamojo Bell, acknowledged as the greatest elephant hunter of all time; men like the valiant Sasha Siemel, who tracked killer jaguars though the Matto Grosso armed only with a spear. Buy Now