“If I have any legacy, I want it to be that of an artist who was passionately in love with Africa.”

Who Goes There?

Ross Parker knows the color of truth in African wildlife art. As a native Zimbabwean raised in the dust of ruby red sunsets, he says no day in the bush is more exhilarating than the one which ends around a campfire with the western horizon set aglow in the continent’s mystical primordial twilight.

As one who has been there, I can tell you: He isn’t lying. For 17 years, Parker, a fine art dealer from Fort Lauderdale, has made a career out of discovering young, brilliant painters able to convey the magical feel of the veld. “A great painting, to me, must do more than offer the literal translation of a moment and illustrate the exact number of spots on a leopard’s coat,” he says. “Memorable sporting art has soul. It creates a mood you can never forget, and it provokes a response that transports you out of your living room into a different world, which is what you find in Africa.”

Arguably, scarcely a handful of western wildlife artists, from German Wilhelm Kuhnert to Englishman David Shepherd, American Bob Kuhn, and Canadian Robert Bateman (among selected others), have possessed the power to do that consistently, yet they were outsiders who came, observed and went home.

Parker is convinced that some of the most potent portrayals of Africa’s wild ambiance have sprung forth from a little-known group of indigenous white and black artists, many of them Zimbabwean. One of the most talented members of that elite club, he says, is David Langmead.

Whether painting in watercolor or oil, Langmead is fast gaining a name among wildlife art enthusiasts for his realistic, dramatic portrayals of African fauna and landscapes. As renowned nature painter Kim Donaldson declared of the young Baby Boomer: “This kid, Langmead, is an artist to watch.”

Drawn foremost to the so-called “Magic Hour” of last light when danger and serene beauty converge, Langmead’s narratives, ranging from charging elephants to close brushes with Cape buffalo, are all based on real life experiences.

“David has lived the life of an African outdoorsman,” Parker notes. “He’s not a tourist.”

Parker stumbled onto Langmead’s work while visiting big game artist Shirley Greene (see Sporting Classics, May/June, 2002) in South Africa. Displayed on Greene’s studio wall was a scene that, from twenty paces away, appeared to be a striking photograph of a waterbuck bathed in the classic crepuscular glow of dusk, as the sun fell behind an acacia grove.

The image elicited eU1 instant tingle in Parker. The sensation turned to a swoon when Greene informed Parker that, far from being a photograph, the work was actually a watercolor painting by Langmead. “Seeing the piece made me homesick, because it spoke to the longing for Africa I’ve always felt inside,” Parker says. “Although I have in a large American city, I will always be an African farm boy at heart. This painting was like a dream.”

Sunset at Shashe River

Langmead was born in 1965 in the southern Zimbabwe city of Bulawayo, the same burg that produced artist Lindsay Scott. While he was still a boy, his parents, Geoff and Joy Langmead, moved the family to a small farm outside of Mutare in the Eastern Highlands near the Mozambique border. Beyond the hardscrabble pasture and rowcrops were hinters inhabited by migratory wildebeest, buffalo and numerous varieties of hunt able antelope. Never far away were the predators – lion, leopard, even cheetah.

Langmead’s decision to become an artist crystallized during the 1970s, amid the Rhodesian civil war as the white government was toppled and the former British colony was cut off from the rest of the world by economic sanctions. Despite Rhodesia’s pariah status, Langmead remembers when David Shepherd — then the most famous wildlife painter in Europe — defied the proverbial picket line and came to observe Zimbabwe’s legendary bounty of animals and to support Rhodesian conservationists in saving it.

Shepherd told the teenage Langmead that his own realistic portrayals were not meant to merely document nature, but to commemorate it. If Langmead’s portfolio is anything, it isa testament to making good on Shepherd’s words.

More than a quarter-century ago, along the slope of the Zimbabwean highlands, Langmead grew up traipsing the bush with his parents on hunting hips and trans-navigations of the Sabi Valley, Gonarhezou, Mana Pools and the Matopas.

Like Parker, Greene, Scott and Donaldson, he was indoctrinated into the sacred rituals practiced by elder sportsmen, which began with setting up wilderness camps, scouting out the terrain, and sitting around fires at night, energized by the anxious expectation of what they might encounter when first light arrived.

Langmead would listen to reverberating roars of lion, the brassy vocalizations of elephants, the rumbling hooves of unseen animals down the dry washes, and the stem warnings of his parents to be mindful of irascible Cape buffalo.

Under the stars he drew imaginary lines through the cosmos connecting the dots of the Southern Cross. He experienced an untamed world, not as an abstraction, but on its terms, with rifle in hand. Consequently, on such evenings, he never slept much but he absorbed the scenes in his marrow.

Back then, he says, he was too young to fully comprehend the effect it all had on him, and he had not yet awakened to the fact that during his lifetime, wildness would begin to slip away Swiftly with political turmoil.

“Unfortunately, the country of my birth, Zimbabwe, is in crisis, and my heart aches when I hear that up to sixty percent of its wildlife has been decimated,” he rues. “However, South Africa is a new democracy and by comparison is full of challenge and opportunity. Life here is vibrant and dynamic.”

Fleeing the social unrest in his neighboring homeland, Langmead today resides in the small rural South African village of Nieu-Bethesda, located at the toe of the Sneeuberg Mountains of the Great Karoo. On clear days, the profile of austere Compass berg, the second highest peak in South Africa, looms large from his studio window.

By his own admission, Langmead calls himself a fanatic when it comes to getting outdoors to gather material for his paintings. “I am definitely a type A personality,” he confesses. “I have a passion for each moment of this life. There is no problem that is not soon converted to a challenge, and I work with the obsessed fanaticism that seems to afflict many an artist. I relish each day, going into my studio to reengage the creative process.”

Watchful Eyes

A typical working day for Langmead commences with a pot of brewed ginger rooibos tea and his preference is to paint only by natural light falling into his studio. Flanking him always are four or five paintings in various stages of development. Of note, U.S. Everglades scenes following a camping trip there with Parker.

“The Everglades remind me of my visits to the Okavango Delta in Botswana,” he says. “Both are places of lush, luxuriant growth – sedges, palm stands, reeds — all in a labyrinth of waterways.”

Beyond the old farmhouse that Langmead and his wife, Bronwen, are in the process of restoring, is a landscape that pulses with the distinct personality of four seasons. Sounding almost poetic, Langmead explains: “Summers are hot, bleached and dry with dust devils hurling their white corkscrews against the valley walls, and relief from the heat comes in the form of dramatic electric storms.” As for the other seasons, he adds: “Spring and autumn are mesmeric times of delicate beauty, with an array of color and lighting effects to dazzle the soul.”

Historically, the Sneeuberg Mountains, like the Serengeti in East Africa, teemed with wildlife and this abundance was one of the principle reasons that San Bushmen sought refuge here during their war with 19th century white settlers. The contemporary wildlife symbol of Langmead’s valley is the kudu bull, presiding over harems which move between the river corridors and grasslands that erupt in neon color following spring rains.

In spite of the serious problems southern Africa faces, there is good news. All around the Eastern Cape Karoo, sheep ranchers are allowing nature to take back vast expanses of scrub pasture, and managing their property for wildlife, which is attracting Americans to hunting and photo safaris. New national parks are planned, too.

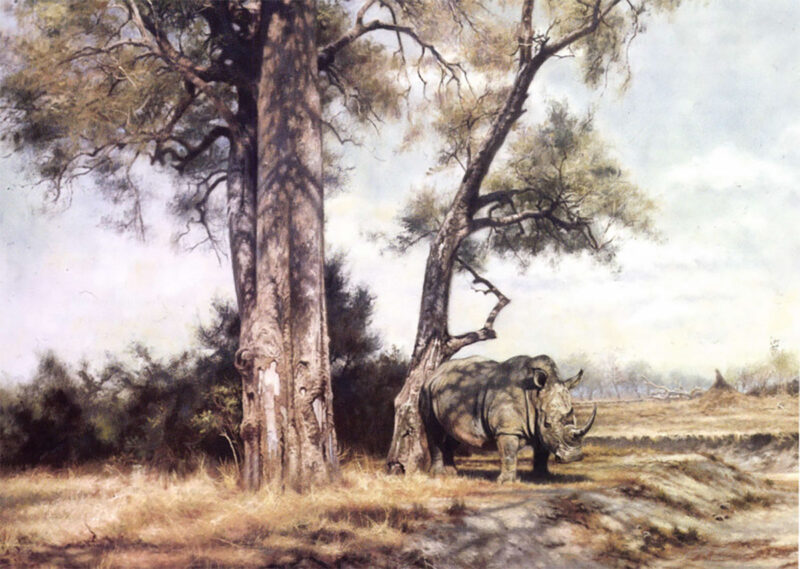

Along with wildebeest, mountain rheebuck, eland, klipspringer, springbok and other antelope are growing populations of leopard in the mountains and common predators such as aardwolf, jackals and rooikats and bat-eared foxes. Complementing the conservation gains on private lands is the presence of Mountain Zebra and Addo Elephant national parks, an how-‘s drive from his front door, that afford sanctuary to rhino, buffalo, cheetah, zebra and elephant.

Langmead has been known to paint for 24 hours straight, rewarding himself upon completion by driving out in the countryside to embrace the rising sun. And he’s always thinking about the next scene, whether he’s with his wife and young son and daughter at Kruger Park for a vacation or hiking through the Karoo. When he needs to recharge the batteries, he heads for the Tuli Block in Botswana and camps along the Shashe River beneath the cathedral pillars of ancient trees towering over a nexus of elephant trails and predator day beds.

“In this place I feel absorbed,” he says, “swallowed up by the massive power and consciousness of rhythms that have reverberated for millennia.” This is the kind of reverential emotion he brings to canvas.

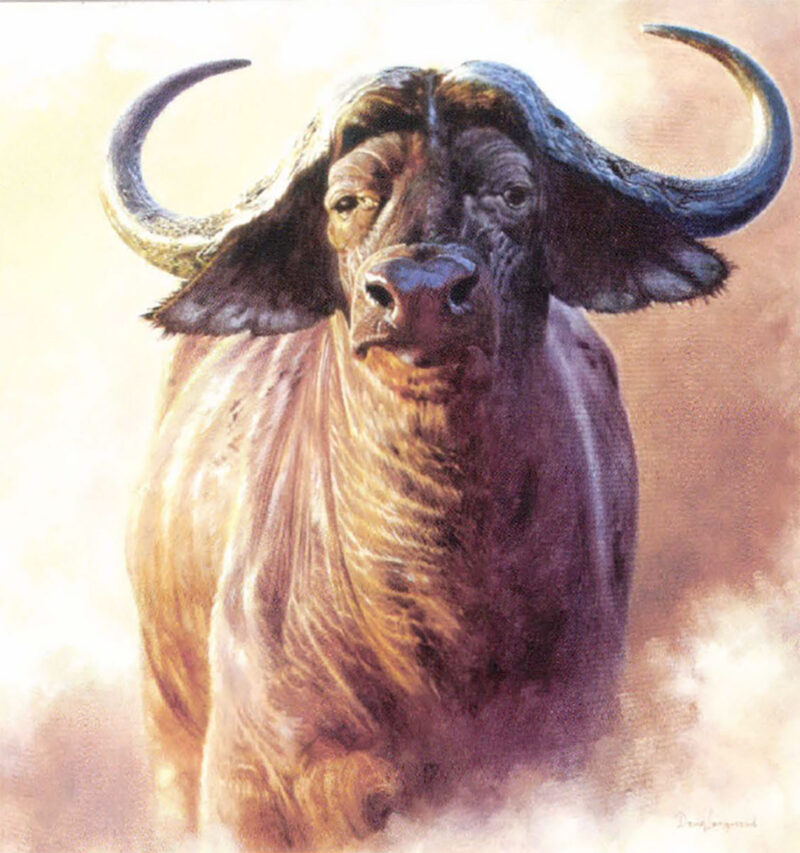

In his painting Dangerous Liaisons, he invites the viewer to contemplate a reminder of Africa’s ability to command humility and respect. His stage is an estuary along the shores of Lake Kruiba, where Langmead, his father and brother were going to fish. As they crested a knoll, a large snorting buffalo appeared on the other side. Instinctively, they tossed their gear and darted into a tangle of deadfalls, with horns on their heels. As they scrambled to safety, the buffalo returned to the point of encounter and proceeded to stomp their rods and tackle into the ground.

In his large oil, Who Goes There?, he recounts the adrenaline rush of a walk that he and Bronwen took to the Shashe River. While following a game trail through a dense thicket, they encountered a baby elephant and within seconds the trumpet of the matriarch descended on them from above. “It was not a time for standing one’s ground, as matriarchs don’t mock charge in these situations,” he says. “Fortunately, we had both been good sprinters in school, and the race back to camp was filled with the sound of crashing bush.” On this day, the pachyderm matron turned around.

Afterglow (detail)

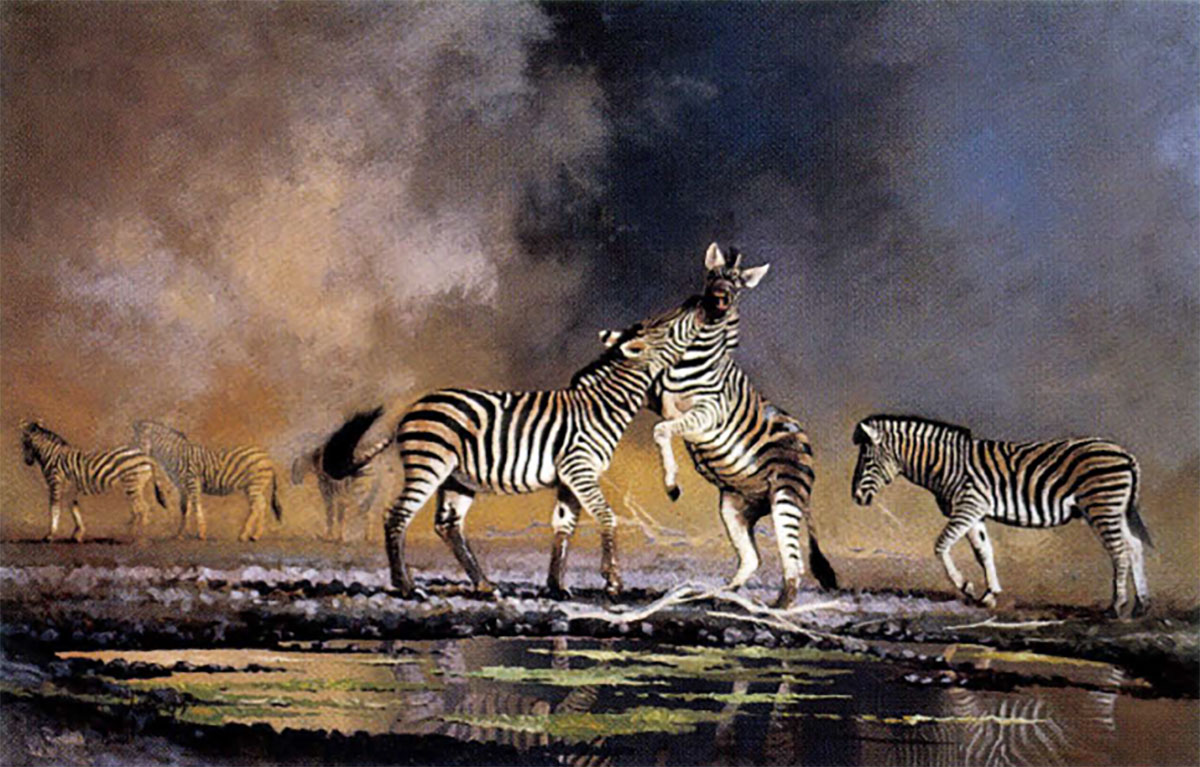

Africa may be called the Dark Continent, but artistic expression of it lies in conveying the light, Parker says. Dry season dust kicked up by the winds and massive movement of animal herds saturates everything in a tint of rouge. Experienced painters like Langmead understand the way that light refracts and reflects, seeing splashes of color hidden even in the shadow beneath an elephant’s belly. In Sunset at Shashe River, he wields colors that other artists are blind to seeing. Retreating into the background is a vastness as deep as the human imagination, while in the foreground, game animals nervously approach the water.

Even David’s pure landscapes, Parker says, profuse an extra-sensory quality when you see them up close. “You feel as though you can whiff the stirred-up dust and the dry grass and the sweet scent of mopane,” he says. “In David’s skies, there is the hint of an approaching storm, the kind that reveals itself to you when put your nose to the breeze and smell the rain coming from 20 miles away.”

The first Langmead paintings shown in the U.S. were displayed at the 2003 Safari Club Exposition in Reno. All five of his works featuring African sporting scenes sold quickly. Later in 2003 another Langmead, a watercolor of ibis, was juried into the prestigious Birds in Art exhibition hosted by the Leigh Yawkey Woodson Art Museum. And then Parker’s Native Visions Galleries premiered several of Langmead’s paintings at Safari Club, which prepared him for a major one-man exhibition of 16 works in 2005.

“When Americans view my work, I hope it will move them to think of the rich diversity of natural beauty here in Africa,” says Langmead. “There is texture and nuance to attract the most travel-hardy soul.”

Although these days Langmead totes a sketch kit in place of his rifles, hunting guides regularly invite him to their bush camps where he makes drawings of trophies and skins to use as reference material. Upon their return home, more than a few Yankee and Canadian hunters have phoned Parker to purchase original Langmeads as vivid reminders of their experiences in the bush.

Buffalo Soldier

Today, out of personal passion for their subjects and rational self- interest, Langmead believes deteriorating environmental conditions in the world present African artists with a call to action, a chance to sway the opinions of leaders in power and future generations that we need to be responsible stewards, just as Shepherd affected him.

In corporate board rooms, public museums and on den walls, his work is having its own subtle impact. “I hope my paintings serve as reminders that beneath all the industry, mechanization and development, there is a fragile ecosystem that sustains the whole of life,” he says.

“If I have any legacy, I want it to be that of an artist who was passionately in love with Africa.”

David Langmead wouldn’t have it any other way. It is, after all, his home.

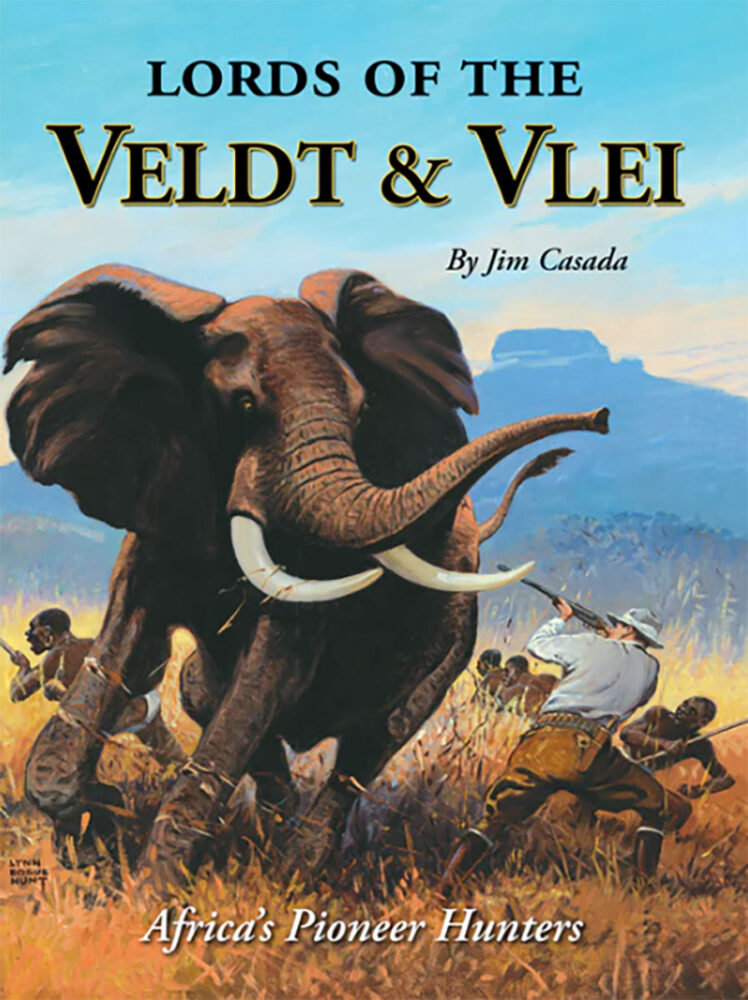

Well into the 19th century, most of the interior of tropical Africa was terra incognitae. Aptly styled the “Dark Continent,” wildest Africa was unknown, unexplored and unhunted. With the dawning of the Victorian era, however, all that changed. Driven by the allure of incredible hunting opportunities and the opportunity to win lasting fame through geographical discovery, intrepid individuals sought fame and fortune in the vast area where ancient maps carried notations such as “here be dragons.” Buy Now

Well into the 19th century, most of the interior of tropical Africa was terra incognitae. Aptly styled the “Dark Continent,” wildest Africa was unknown, unexplored and unhunted. With the dawning of the Victorian era, however, all that changed. Driven by the allure of incredible hunting opportunities and the opportunity to win lasting fame through geographical discovery, intrepid individuals sought fame and fortune in the vast area where ancient maps carried notations such as “here be dragons.” Buy Now