The hut smelled of must and dampness. Slivers of light pierced through thin gaps in the grass walls. The old shaman sat with his legs crossed. His dull, green eyes seemed void of life, staring through rather than at them. His skin hung on a bony frame and his voice wavered when he spoke, as if even his vocal cords were as wrinkled as the rest of him.

“The old man say it is not tiger. He say it is phantom who feeds on the souls of children.”

“Why children?”

“There is old legend of boy prince who lost his mother to tiger while she performed works of mercy for poor children. This prince blamed not only tiger, but children as well. He hunted and killed many tigers. It is said he once stood by without emotion and watched tiger stalk and kill young girl when he could have prevented it. After that, as legend say, prince—he just disappear. Old man say you cannot kill tiger with bullets.”

“Does he say how I can kill it?”

“He say you cannot kill it. He say tiger only stop when he have fed on enough children to satisfy his revenge.”

Steven did not believe in phantom tigers. Though myths of vengeful princes or reincarnated brutal rulers permeated throughout local lore. Sometimes people needed ways to explain away extraordinary events. In attempts to increase their influence over villages, witch doctors often relied on the people’s willingness to believe in such myths. This old man, however, seemed sincere in his belief. Even if Steven thought it rubbish and even if tribal leaders offered no useful information, he found it always good policy to visit with village elders.

When they found the kill site, Steven traced the fresh track with his fingers. It was the same tiger—the biggest track he had ever seen. Every few steps it slightly dragged his back right foot in the sandy ground. Then Steven glanced at the bloody hand — the smallest yet. His gaze did not linger.

He had hunted man-eaters before, and when local authorities came up short in their attempts to gun down a problem cat, they often turned to hunters such as Steven. Most often, the “authorities” had little experience with wildlife, but possessed all the guns. Smart tigers, such as this one, knew how to avoid big groups of men using drives and spraying bullets at everything that moved. Tigers rarely succumbed that way. Usually some distant patrol stumbled into a cat 50 miles from the last sighting and shot it on site. Without any evidence it was the right cat, they often called the case closed until another incident had villagers dreaming up ghosts and evil spirits. Too often, half a dozen tigers that had never harmed anyone died while one man-eater continued roaming the jungle searching for its next victim.

Steven used to enjoy hunting. His father trained him to shoot, and they chased rabbits and deer and upland game on Nebraska’s prairies. He left there when he was mostly still a child. His grandfather, a missionary, whisked him away and offered him an education of life in Third World villages. Finding a hunter’s paradise in Kenya, he made it his home.

Spirit of India by Ezra Tucker, acrylic, 48 x 36 inches.

He eventually made a name for himself guiding high-paying overseas hunters there before the government shut it all down. He once had a three-year period with a 100-percent success rate on both lions and leopards. It had been unheard of. When potential clients brought it up, Steven always told them some hunters were just lucky. And in many instances, that was true. Like one last-day leopard where they had mostly given up. On the hunter’s last morning, they sat near a recently fed-on bait and waited until the sun looked directly down on them before giving up. During the drive back to camp, one of his trackers spotted a leopard sneaking beside a korongo 200 yards away. After a quick stalk, the client put a bullet in its heart and kept the streak alive. Shooting a leopard in that way was about as rare as finding a three-horned kudu.

Things were different now. His fame as a cat hunter had captured the attention of prominent Indian politicians who quietly wanted to dispose of certain problem cats. His first tiger had been a young female roaming too closely to a local farming community, occasionally killing livestock. By the time Steven arrived, the tiger had been seen twice in daylight watching the field hands as they returned from harvest. He killed that tiger the first night by waiting in a machan looking down on the cattle. His recurring luck turned him into somewhat of a celebrity almost overnight.

Steven’s reputation or ability failed to touch that of a Corbett, but he worked cheaply and had few other obligations to call him from an assignment. He wished he had said no to this one. He wished Corbett were still around to take care of this deadly cat.

They never told him this big male tiger had a taste for children. In fact, they had not told him much at all. They called. He answered.

He was glad to have Samarth with him. Samarth did not cower in the shadows or fall victim to silly legends. Samarth was a good man, a trusted friend—usually enthusiastic on a hunt, usually willing to spend however many nights in an uncomfortable machan or in a blind beside a half-eaten carcass of a Haryana cow. This time, Samarth kept coming up with reasons why it would be best for him to be in the village following leads. Yet, Samarth remained loyal to Steven’s requests. They had spent seven different nights in machans beside bloodstained ground where the remains of a child had been moved to a more respectful resting place. But this tiger never returned to a kill. And Samarth grew more nervous with each passing day.

“I do not know how we will kill this tiger,” Samarth said. “This tiger does not behave like other tigers. He kills for pleasure. He does not drag his prey and feed where we can track him. He feeds little then moves on.”

“Don’t tell me you’re falling for those ghost stories,” Steven said.

“I have never seen a tiger like this,” he said.

“It is just a tiger, my friend. It is a tiger that has found the easiest of prey. How long before the villagers turn on us?”

“They grumble now. Some say you make tiger more angry with your presence. Some say you have a deal with tiger.”

“What do you think? Do you think I have shaken the hand of the devil?” Steven smiled at his friend.

Samarth’s expression remained stolid. “I think we should kill this tiger and go home. I think I am glad I moved my wife and children to Bangalore.”

“You think the city is less dangerous?” Steven asked.

“I think tiger like this make people do bad things. It spread fear. It make my son and daughter afraid to go outside. Maybe they never lose that fear. I wish for them to have good memory of the jungle — even of most tigers.”

“How do we outsmart this cat, my friend?” Steven asked, abandoning his smile.

“I do not know. He does not behave like tiger. He behaves like prince in the legend.”

“This tiger is not a prince. It is not a ghost. It is a tiger. That is all,” Steven said.

“Then we must hunt it like tiger,” Samarth said. “And we must hope for luck.”

“Why do you think he attacks children?” This tiger had attacked at least seven adults as well, but the ratio of children to adults grew by the week. And the victims kept getting younger.

“I cannot say. I only know what he does. Only tiger and God know why.”

“I’m not content hoping for luck,” Steven said. “Not with this one.”

“You will not like it,” Samarth said.

“I do not like it now.”

Samarth nodded. “Come. Let us follow the tiger track. It will tell us what to do next.”

They followed the spoor to a tributary of the Tungabhadra River, where the water ran wide and swift. There, the tiger turned north, using the low-cut bank as a trail upstream. Once, the tiger stopped for a drink and had turned to watch behind it. Other than that, its steps were purposeful, almost rhythmic.

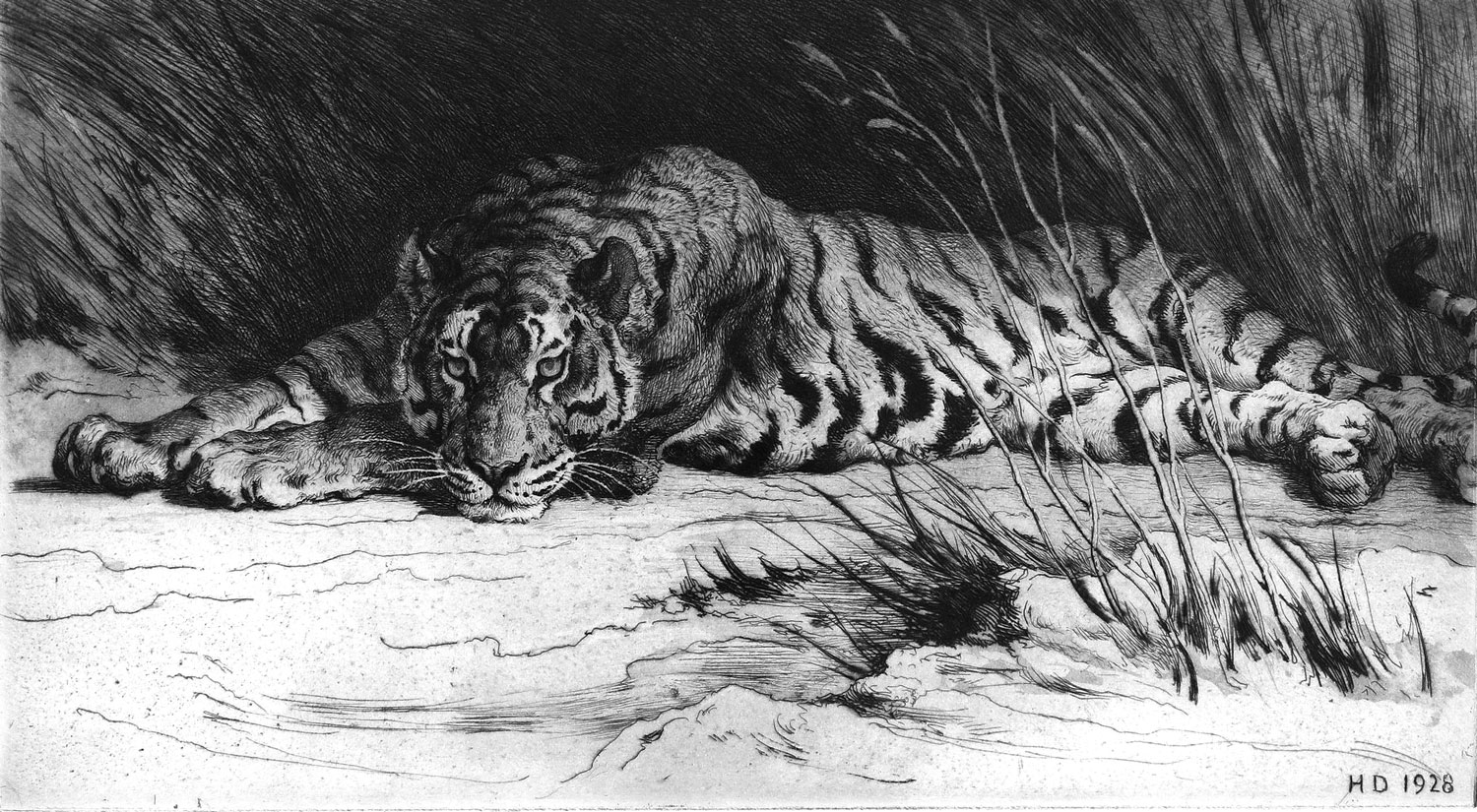

Tiger Resting by Herbert Thomas Dicksee, etching, 9 x 11 inches.

When they stopped for a quick bite of cheese and bread, Steven turned to Samarth. “This tiger does not follow a pattern. He stalks from village to village. Sometimes he returns to a village three times in two weeks, some he attacks only once, others still, he returns after many months. Where is he going now?”

“He go to cross river. He do not look for crossing. He go to place he cross before. A pattern. We find where he cross, then we wait.”

“How many children does he kill while we wait?”

“It is not for us to know. But I think here our best chance. Here we end his terror.”

Steven took a thorn and jabbed it into the track of the tiger’s back right foot. An old superstition he had learned while hunting lions in southern Africa. If the cat’s back leg were injured, maybe the thorn in the track trick would slow him further. Steven usually shunned the old magic, but he pushed the thorn deep into the dirt and twisted it before moving on.

They found the crossing halfway through a dark thicket they had to crawl into. They would be nearly defenseless if the tiger backtracked and hunkered in the shadows waiting to strike.

A fallen tree, slick with moss and water, had created a narrow bridge only the smallest or most nimble of creatures could cross. The tiger’s tracks led to the tree’s uprooted base and his fresh claw marks scraped over layers of old ones. He had used this crossing many times.

“This is where we will find him,” Steven said.

Samarth turned his eyes away to hide his fear.

Steven placed his hand on Samarth’s shoulder. “You have done well to lead us to his crossing.”

Still unwilling to look his friend in the eyes, Samarth turned toward the trees. “There is good tree for machan. We must build it quickly.

The machan turned out to be a platform made from a few fresh-cut branches tied under the crook of a tree 15 feet into the air. By design, it was only big enough for one person.

“I will not stay tonight,” Samarth said. “I must send word to my family that we are close to finding tiger and to quit now would not be honorable.”

Steven smiled. “You are a good friend, Samarth. And a good man. I am glad you are here. Go. You will not miss the tiger. He will not cross back this soon. But I want to be here when he does. I will see you in the morning.

They shook hands, Samarth helped Steven into the tree and then he followed a sambar deer trail away from the river.

Alone, Steven listened to the water carry the jungle’s ancient secrets toward the ocean. A muntjac barked. Steven smirked. Samarth’s step had grown loud with age. There was a time when the old Indian tracker could sneak up on the spookiest of deer. Too much time in the city had given him flat feet.

Steven’s smile faded. He had that feeling. One he had come to trust without question. It had saved his life in Tanzania with an old, nearly toothless lion that turned to stalking easier, two-legged prey. On a dry, hot afternoon hiking down a well-worn path to a nearby Kikuyu village, he had that same feeling. It was strong enough that he decided to sit beside a termite mound and mull it over. As was his habit while hunting problem animals, Steven sat with his rifle resting in his lap, his hand wrapped around the grip. He sensed something in the bush watching him. He did not hear anything. Did not see movement. Just that nagging some of the old timers called a sixth sense. Sometimes it turned out to be nothing, but often enough it prophesied truth. After sitting long enough to dismiss it, he stood intending to continue toward the village.

The brush to his right exploded. He turned just in time to see the old beast hammering toward him, grunting with every step. Steven dropped the ancient lion with a brain shot at ten steps.

In the Reeds by Herbert Thomas Dicksee, etching.

Now, that same feeling of being watched, maybe even hunted, gnawed at the back of his neck. He listened to the breeze below the water’s rumble. He listened to the silence below the breeze. From in the tree, he could see upstream for another half kilometer before it slithered around a bend into the darkest part of the jungle. He leaned out to get a closer look. Just below the bend, a small series of falls cascaded lightly over a submerged rock outcropping. The water looked shallow.

Samarth screamed—a horrified raspy scream. The scream of a man facing a sudden and violent death. Even from hundreds of meters away, even through the higher pitch and scratch, Steven knew the voice belonged to Samarth. And when the shriek cut off abruptly, he knew what that meant too.

Steven slung his rifle and shinnied down the tree anyway. He ran down the path, his heart pumping with fear and a thread of hope. With his rifle now in his hands, he ran like he had never run before, with a purpose he had never experienced. He knew man-eaters, but this was his friend. Samarth deserved better. His family deserved better.

After racing through a small clearing and into the heavy trees again, he slowed to a walk. The tiger would have attacked from the thick bush to the right. If Steven were a tiger, that’s where he would have attacked from. He crouched and studied the ground. Samarth’s tracks were those of a man out for a stroll. They had thought the tiger had been across the river, leaving little need for extra caution.

A few more meters and Samarth’s tracks simply vanished. He hadn’t even seen it coming. The impact from the tiger had lifted Samarth into the air and into the heavy undergrowth. Steven swallowed hard. Sweat tickled the side of his nose.

Crouching, he stepped slowly into the leafy bushes. The air cooled. He stopped to listen. The silence was maddening. Nothing stirred; the breeze seemed to hold back.

Samarth had children. He was a dedicated father. The tiger had no right.

Steven remembered the day his own father had slapped him for forgetting to clean the old man’s shotgun. The same week his mother had left. It was the first time his father had struck him in a drunken rage. His father drank a lot after that day. Steven had run into the woods behind their ranch. He planned to stay there until his father came looking for him. The sun set and grey faded to black. Shivering, he wandered along Lodgepole Creek, searching for a warm, dry place to lie down. He was tired and frightened and lost. The anger he felt toward his father eventually faded. He wanted to go home. Sniffling through tears, he found a dark hole in a dry embankment.

He heard light grunting and scratching and crunching from inside the hole. He inched forward anyway. The hole offered warmth and relative comfort for the night. Worst case, he thought, it was a raccoon gnawing on a bone. He had shot plenty of raccoons. This one would slink away into the night when it saw him approach.

His father would not come. He knew that now.

Young Steven leaned in close to the hole, squinting his eyes into the blackness absorbed inside the den. The grunting stopped. Steven’s muscles tensed as he waited for the scamper of feet.

Nothing.

He leaned in closer, so close a blade of grass tickled his forehead. The light outside was grey and the air smelled musty. Steven snatched up a nearby stick. It had the circumference of a 50-cent piece and was as long as a ruler. His fingers tightened around it.

“Go on, get,” he said and jabbed the stick into the hole.

Nothing.

The raccoon must have been deep in the back. Gaining courage from his previous attempt, Steven eased farther in and thrust with his arm until his shoulder touched the outer edge of the lair.

It felt like a sharp sting at first, but as the teeth clamped into his thumb he cried out in pain and tried to pull free.

Whatever was in the hole growled and yanked. Steven no longer believed it could be a raccoon. He did not care what it was. He just wanted to be free. He cried out for his dad. He cried out for his mommy.

Nobody came.

He struggled to free his arm from that hole for two minutes before the flesh ripped free from the base of his thumb. He toppled down, immediately pushing himself up with his good hand. Just before turning to run, he saw a badger shuffle from the lair, hissing and snarling. He ran. He ran crying and bleeding and searching for his father. He finally stumbled to a road and a stranger drove him to the hospital. His dad did not come pick him up until noon the next day. Within six months, his grandfather walked him away from the ranch for the last time.

Now, like that cold night, Steven felt alone. He took another step into the heavy brush and stopped. He heard bones crunching. The tiger was feeding on Samarth. Steven heard the tiger grunting and breathing heavy. A few more steps. If not for the heavy brush, he might be able to shoot the tiger in the ear.

Sweat dripped from his nose. Steven heard it splashing on leaves below him. He was aware, alert, a predator stalking in for the kill. Then he noticed it. The silence. No grunting. No crunching. No breath. The tiger had gone quiet.

Steven reached his hand out to push a leafy branch from his view. His fingers trembled. The old scar on his thumb ached. As he moved the moist leaves, a heavy shadow gave way. Six meters farther, the brush was black with blood and gore. Samarth’s cheek was gone — a fractured red-stained bone left the side of his face looking alien. Death by nature unimaginable.

Where was the tiger? Steven felt like he was reaching into that dark hole from his childhood. He had never been more frightened. He glanced at his friend one more time. There was nothing he could do. Then, even though he knew it was a mistake, even though he knew the tiger would pinpoint his position, he turned to run.

Just before everything went black, Steven noticed the tiger, ready to pounce from the shadows beside the trail.

It was the last documented kill attributed to the Prince of Karnataka.

Weeks later, the news of Steven’s death reached a small community in Nebraska where he had been a stranger for 15 years. An old man, sitting alone on the porch of a rundown ranch stared blankly toward Lodgepole Creek where his only son had once been bitten by a badger.