When I was growing up in the late 1960s, my father had a gun cabinet in the living room. In the days before steel vaults, it was considered a centerpiece of décor. In the cabinet were the guns one would expect of a man who, to make ends meet, laid brick, painted houses and washed windows on his days off.

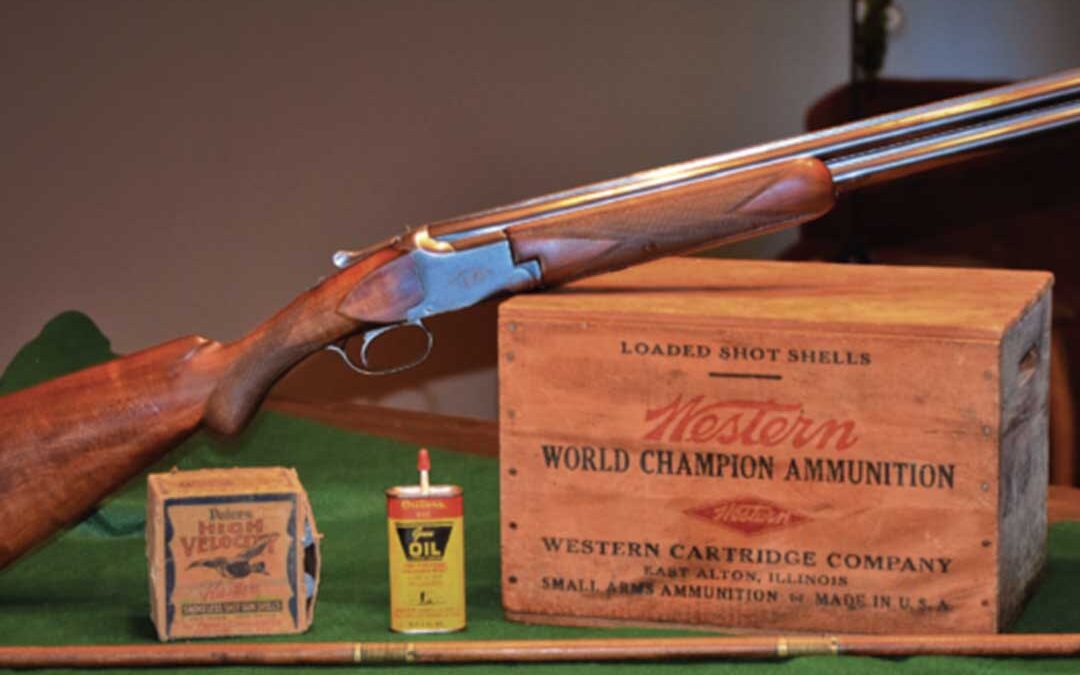

There was a Marlin bolt action .22, a Winchester Model 42 shotgun that his father has won on a punch board in the ’30s, a Winchester Model 88 (post 1964), a Remington pump .22, and a worn-out Winchester Model 97 purchased at a Western Auto store. But one piece stood out among the other working-class guns: a Belgium-made Browning Superposed 12 gauge.

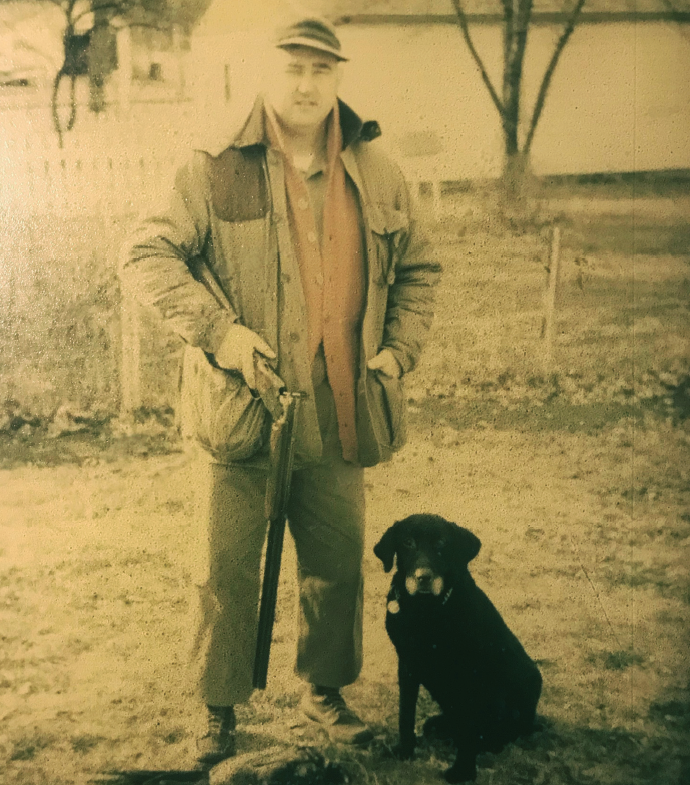

The author’s father, Clayton Chalstrom, poses with his treasured Browning Superposed and his Lab, Blackie, after a pheasant hunt in Fort Dodge, Iowa in 1970.

Dad told many stories about the Browning. In 1955 he traded an AYA Matador, which never seemed to fire one barrel at a time for the Browning. He scraped every penny he had to purchase what he felt was the most quality shotgun on the market. An avid pheasant hunter, he wanted simply the best—a gun that would be reliable and, more importantly, durable.

The Browning was truly beautiful. It became an appendage of my father, along with his Bob Allen hunting coat and the various black Labrador retrievers that he trained. Choked in improved cylinder and modified, it was the perfect shotgun.

I have never seen a better shot in my life than my father with the Browning. Pheasants had no chance when it was in his hands. Each fall prior to the season, he would shoot carefully reloaded trap loads and practice on clay pigeons that I pulled.

Dad used the Browning through Iowa’s pheasant hunting glory years from the 1950s to the early 1970s. It was his all-purpose gun used for pheasant, rabbit and the occasional partridge. A solid piece of weaponry that fit him like a glove.

I was only 4 when I first saw him shoot the Browning. It was his day off and my mother was volunteering at the neighborhood elementary school. He loaded me up into the 1970 Dodge Polara station wagon along with his favorite Lab. Soon we were walking down an abandoned railroad track, the dog in the ditch. I spent my time collecting old railway spikes. Suddenly, the dog stopped, his tail circling. Two roosters flushed. The Browning leapt to my father’s shoulder as if it had a life of its own. The first bird fell almost instantly followed by the second only a few seconds later. The dog quickly retrieved the birds and we headed home.

Back home, dad followed his usual ritual. He took the Browning out of its case and sat it next to the heat register for an hour. He claimed it took any hidden moisture out of the gun. He then retreated to his workroom in the basement, disassembled the gun and thoroughly cleaned it. The smell of Hoppes number 9 permeated the house. After cleaning, he wiped it down with an oily rag and placed it carefully into the cabinet.

“Never, ever, have a dirty gun.” Dad instructed me. “Especially a gun as fine as this.”

Dad used the Browning through the lean pheasant years of the 1970s. It was during this time that he allowed me to hunt for the first time with a gun. He relinquished his Browning to me for the day and used his old 97. Not knowing the etiquette of bird hunting, we were walking a stretch when I saw a rooster pheasant sitting in a tree. I stopped, pushed off the safety, and shot my first bird.

Proud as I was, Dad quickly admonished me. “Let them fly! That’s their only advantage!” This was the only time he spoke of the heresy I’d committed.

Dad retired in the late 1980s. He felt he was slowing down and decided to purchase a lighter shotgun, a 16-gauge Citori. The Superposed became his backup gun, the one he would turn to when he felt it was necessary.

During his many trips to the prairies of South Dakota, Dad would sit in the motel room with my friends holding onto the Browning. In great detail, he’d recount his adventures with his favorite shotgun while we all politely listened.

The Browning would become a “lender” gun to his son-in-laws when they arrived for the holidays. Once, on a very cold New Year’s Day, my brother-in-law slid down a steep bank and crashed through the ice of a drainage ditch. The Browning plunged into five feet of icy water. Aware of the sin that had been committed, we dove underwater to retrieve the reliable Browning. It was below zero with a 20-miles-per-hour wind and a half-mile walk back to the Jeep that my father was guarding. By the time we arrived, we were both walking like the Tin Man from The Wizard of Oz, our clothes and skin frozen solid. Dad’s first words were not about us, but rather, whether the gun was okay. The next day we took it to a gun shop where it was thoroughly cleaned.

My father lived to be 86 years old and hunted well into his early 80s. When heart disease ravaged his incredibly muscular stature into a shell of a man, he laid in a hospital bed for seven weeks. As I sat next to his bed, intubated and unable to talk, he grasped my hand and pointed to a letter board that had been created for him to communicate. It read: “Take care of the Browning and get it fixed. Give the Citori to your son.” Dad died a few days later.

I did as he asked and took the gun to a trusted gunsmith. The lever on the Browning was well to the left of center; it fell loosely when opened.

My friend said, “I can’t fix it, but I can send it off to a respected gun-restorer in Missouri.”

After the gun arrived, the restorer called and said that he’d never seen a gun that had had so many rounds fired through it and that it would have to be entirely rebuilt. I consented. He asked if I wanted it re-checkered and blued. I declined.

Once I had the gun back, it looked as it always did. Worn checkering. Stains built by years of sweat from my father’s hands. A scratch on the butt from an excitable young Labrador puppy. Yes, it was perfect.

The first day of the pheasant season, I relinquished the use of my Winchester Model 23 that had been my bread and butter for 20 years. I took the Browning Superposed out of my father’s leather gun case. Worn looking but essentially new. A phoenix raised from the ashes, but still possessing the marks of an honest, hardworking man who felt that, in the field, one deserved the very best.

Within minutes, my German wirehaired pointer locked up. Two roosters flushed. The Browning leapt to my shoulder as if it had a life of its own. The first bird dropped, then the second rooster took a heavy load of No. 6s and dropped as well. The dog quickly retrieved both roosters. With the birds in my bag, I caressed the nape of my beloved dog, and then I bent to my knees and cried. A poor man can only afford the very best.

Michael McIntosh offers practical advice on buying, shooting and collecting older guns–what to look for and what to look out for, all based on long experience. McIntosh also offers advice on buying and shooting older guns–what to look for and what to look out for, all based on long experience.

Michael McIntosh offers practical advice on buying, shooting and collecting older guns–what to look for and what to look out for, all based on long experience. McIntosh also offers advice on buying and shooting older guns–what to look for and what to look out for, all based on long experience.

As interest in fine double guns reaches a new high in this country, Best Guns serves as both a guide for the uninitiated and a standard reference for the experienced collector and shooter, all written with the precision and seamless grace that were Michael McIntosh’s trademark style. Buy Now