No, Dad never hunted, but he taught us how. Always show up. Play fair. Play hard. Never complain. Give more than you take. And whistle while you work.

Dad wasn’t a hunter, but he was an enabler.

We were farm kids, mostly, third-generation Norwegian and Kraut and Bohemian and Dutch immigrants, but we put no hyphens in front of American. We were racing the Russians to space and Roger Maris was chasing Babe’s home run record and the British bad boys of rock and roll had a whole lotta shaking going on, but the biggest thrill in rural South Dakota was hunting. Pheasants in the corn, ducks in the sloughs, jackrabbits in the pastures and plowed ground. So we went hunting, every chance we got, without Dad.

Walther Philip Spomer worked. Everyone’s dad worked back then, and most moms. Six days a week, often seven. They’d all come through the Depression and took nothing for granted. Next to godliness and cleanliness, hard work was the greatest virtue. Life had to be wrestled from the black prairie earth, and it didn’t roll over easily. During his 82 years Dad grew the corn, raised the beef, butchered it, turned it into sausage, cooked it and served it at his small town cafe. He also managed to shingle every church in town and paint half the barns and houses in the county. But he didn’t hunt.

“I think they’ll end up burying you with that baseball.”

He left the house in the dark, whistling, and returned in the dark, whistling. Dad whistled while he worked. But he’d stop working when someone needed a tenor to sing the Lord’s Prayer at a wedding or funeral. That was nearly every weekend. In his later years he mowed lawns and shoveled driveways for widows, took food to shut-ins, visited old folks he didn’t even know in the Good Samaritan Center. In his younger years, every summer, he made time to coach Little League baseball.

A son should write about a father like that, pen one of those “last hunt” tear-jerkers about how the old man took his old dog for one last pass through the cornfield or handed his boy the old Model 70 right after he shot his last deer with it. But I can’t, because Dad wasn’t a hunter, though he could have been.

Look up hand-eye-coordination in the dictionary and there’s a picture of Dad. Walt could hit anything he threw at with anything he threw. Darts, balls, rocks. He once flung a stone at a streaking cottontail his sons had missed with .22s—and cold-cocked it. Imagine what he could have done with a shotgun. Typically, however, he threw baseballs. The man was nuts about baseball.

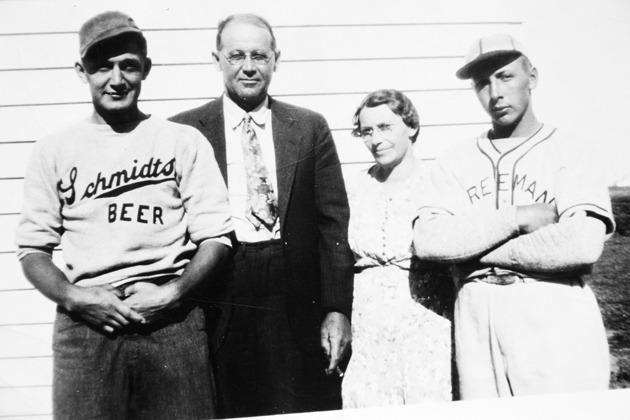

“Walther! What have you in your pocket?” a primary school teacher once demanded.

“It’s just my ball,” Dad reportedly replied, instinctively reaching for the familiar rasp of stitched leather. He got to keep the ball but went home with a letter of reprimand, which prompted a half-hearted scolding from his mother. “Walther. You and that baseball. I think they’ll end up burying you with that baseball.”

His dedication to baseball paid off, as the MVP trophy from a 1949 Sioux Falls tournament proclaims. Dad played shortstop and third base and first and second unless he was pitching or catching or roaming the outfield. He never cursed, never argued a bad call. “We’ll get it back next inning. Just go out and play good ball. Score runs. They can’t beat us if we score more runs,” he’d say.

For a little guy—just five-foot-eight—he had a decent fastball and a good curve, but his sinking knuckler foiled most would-be hitters. It floated in like a balloon, every stitch big as a rope. Then the bottom fell out.

Walt could hit, too, for distance, arms and shoulders sculpted from milking, pitching bundles of grain, lifting quarters of beef. One spring when he was already 40 and just moved to a new town and job, a carload of boys drove up and begged him to be their ninth man so they didn’t have to forfeit the first game of the season. Dad dug his glove and bat from a packing box, struck out eleven batters and hit a pair of doubles, a triple, and a home run. He came home whistling. But he didn’t go hunting.

Dad never hunted, but he taught us how.

I suppose he was disappointed, as most fathers are, when his boys didn’t share his love of the game. We played in high school, but once we’d experienced the adrenaline rush of a flushing rooster, the misty promise of a duck slough at dawn, our allegiance switched from bats and balls to barrels and bullets.

Dad didn’t miss a beat. He saw to it that Grandpa’s .410 single-shot varmint gun was moved from the farmhouse to our bedroom closet. When hard cash was required for new .22s and 20 gauges, he found butcher blocks that needed scraping and meat saws that needed scrubbing at a dollar a job. When we needed adult supervision and transportation to the slough for the waterfowl opener, he assigned his hired man the job and plugged the gap himself, working until midnight. Never complained. When we stomped in with limits of curly-tailed mallards at dark, Dad would take them, whistling, and clean them back in the slaughter room, the concrete floor still wet from its end-of-day scrubbing. When a school band trip took us away from the trap line, Dad was up extra early to run it for us.

He did some of our best scouting, too, right from his butcher shop, café or painting ladder. “Albert Schmidt said something got into his chickens last night and killed half of them. Better get out there with some traps. Bucholz says there’re lots of roosters around his place. Hahn said you should come out and shoot the squirrels getting into his corn.” Dad knew everyone and we reaped the rewards.

Too soft-hearted and generous to make a killing in any business, Dad nevertheless held onto the farm and added a few acres when he could, assuring us we’d always have a share of the good earth our ancestors had suffered and toiled to secure. He even let us establish several acres of set-aside, a small wetland where we now find mallards and pheasants and whitetails. He never hunted, but he knew we’d always want to.

I had vague hopes Dad might take up pheasant hunting when he retired, but he never did. Retire. Seventy-nine years went by and he was still climbing ladders and painting neighborhood houses, collecting clothing for refugees, singing for funerals and, along with Mom, cooking elaborate meals for family gatherings. Pheasant, squirrel, venison, turkey. Anything we’d bring home, he’d turn into a feast. And he continued to help us hunt. “I’ll drive around the end of the field and pick you up,” he’d say, then he’d tour area farms and fields, admiring the crops, the new buildings, old churches and cemeteries while we worked a section for birds.

The heart attacks didn’t even slow him down much. He just made new friends in the hospital and rehab. Then he returned to ushering at church, shoveling snow for widows and singing for lonely folks living out their last years.

No, Dad never hunted, but he taught us how. Always show up. Play fair. Play hard. Never complain. Give more than you take. And whistle while you work.

Walther Philip Spomer died while napping in his easy chair after Sunday services. Just sitting there. We buried him on the South Dakota prairie within sight of the hill where I’d shot my first jackrabbit with the .22 Winchester I bought with dollars earned cleaning his butcher shop. Everyone at the funeral said he looked real natural. There was a baseball in his hand. And two sons, two hunters, standing by, who love him.