One of Ed Zern’s hilarious books is titled How I Got This Way. As you would expect, the book relates the mishaps and misadventures that caused him to develop into the mildly warped personality that wrote some of the funniest outdoor stuff ever written.

I ran across my copy of the book a couple of weeks ago and it caused me to reflect on how anyone gets to be a shotgun scribe. I don’t know of any better term to describe what I do.

Somebody asks me the question at least once a week, and I finally concluded that in my case, the answer is by pure dumb luck. Simply a matter of being in the right place at the right time. Have you ever noticed that some guys have all the luck? Always get the break. Always catch the biggest fish. Always manage to find their way home in the darkest night. Well, I’m one of those guys. I’ve been awfully lucky. And part of that luck simply involved growing up in a place and at a time where shotguns were an integral part of daily life.

I was born in the West, but I was just an infant when our family re-found our roots in Georgia. That was in the late ’40s, and by the time the ’50s rolled around, I was growing up in the rural Deep South. Most folks said we lived “in the sticks,” and I guess we did. The closest thing that we had to organized entertainment was when we got together to kick the crap out of each other at the Friday night football game. In our case, even that barely qualified as “organized,” but it gave us a convenient venue to even old scores with parental approval! There was no movie theater, there were no electronic games. Television and computers hadn’t yet become the universal substitutes for parenting.

What we did have was space. And a freedom granted by tolerant parents. We lived with a modest amount of poverty, which is always a good thing for kids to have. Our environment made us self-reliant and responsible. We had to be, just to get by.

Most families ate game meat on a regular basis. Not that we would have starved without it, but it was a welcome addition to our diet. In our part of the world it was traditional, plentiful, and the youngsters were often assigned the job of getting it.

Of course, this meant that we were introduced to guns when we were very young by today’s standards. Most of us had Daisy BB guns by age of 5 or 6. Since these were introduced simultaneously with the universal rule, “if you shoot it you eat it,” we had the opportunity to try some pretty interesting cuisine.

Any time the chores were done, the Daisy would be strapped across the handlebars of the trusty Schwinn and we’d go off “in search of the Nile,” which was a muddy trickle about a half-mile from our house on the outskirts of town. We ate frog legs and snakes and squirrels and, of course, all kinds of birds. We learned that robins are pretty good, if you like dark meat, and so are English sparrows if you spit them on a stick and roast them over an open fire with a little salt and pepper. The only problem was that it took an awful lot of ’em to satisfy a 7-year-old’s appetite.

The Daisys taught us about basic gun safety, and how to aim and swing. It’s pretty easy to understand the concept of “lead” when the projectile is clearly visible in the air and you can see what is required to put the projectile and moving target in the same place at the same time.

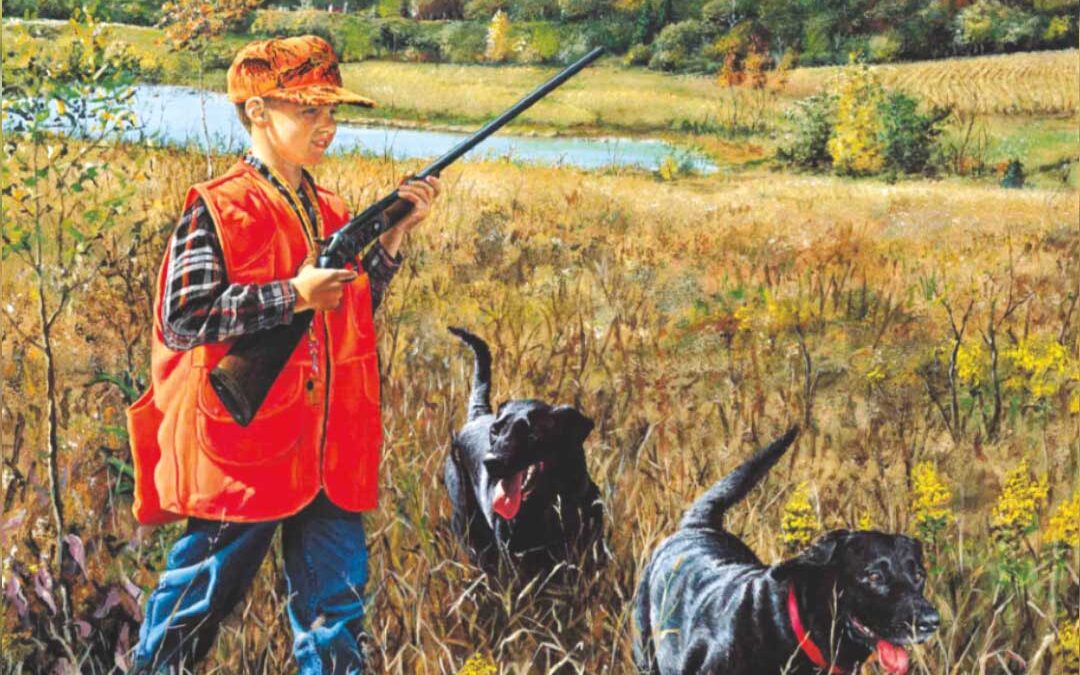

By age 8 or 9, we were introduced to real guns. Most of us gravitated toward shotguns, because they opened the door to “shooting flying” and doves, quail and ducks. Some of us even had our own guns and we were allowed to use them under the supervision of adults who were happy to let even that restriction lapse as soon as we demonstrated the care and responsibility required to use them safely. By age 12 most of us were hunting on our own.

Of course, we live in a much different world now than we did then. Nobody even noticed a kid walking through town with a shotgun, or the 12-gauge Lefever propped in the schoolroom corner. I’m sure that any of our teachers would have been shocked if she discovered that even one of her male charges did not have a knife in his pocket.

In my late teens, shotguns helped to bridge the gap that long had separated me from my father. The times we spent following dogs across fields of sedge and lespedeza helped to blunt the memories of Normandy and Berlin, and points between.

In the tumultuous ’60s quail hunting gave us a common ground, somewhere to meet that we both understood at a time when understanding was a scarce commodity between the two of us.

The fondest memories from my youth are inextricably connected to the shotgun, and the memory of my best friend from those days still walks the fields with me at times when I appear to be alone.

While I was working my way through college, the knowledge of how to “make meat” with a shotgun served me well. Dried beans and potatoes were cheap, but awfully drab without a little meat. To this day I’d rather eat game meat than farmed meat in any form.

In time, shotguns made the natural progression from tools to favored artifacts, objects of fascination, subjects of study and media for artistic expression. No longer mere implements, they have become comfortable companions that color and texture the world of the unrepentant boy trapped inside the graying man, not totally unlike a good dog to walk the lower 40 with, or a good woman to sleep with at night. And I really don’t want to be without any of them, despite having reached the age where the roles of the dog and the woman can be reversed without drastically diminishing either experience.

A lifelong fascination with shotguns has led me to many places that I would not otherwise have gone. It has brought me my best friends, my best times and a life of dreams fulfilled. Because of shotguns, I have traveled the world. I’ve seen the Southern Cross and the northern lights, the western plains and the Eastern Shore.

Without a shotgun, my life would have been little more than a colorless shadow of what it has been, and I feel a touch of sorrow for those folks whose autumn is uncolored by guns and dogs and birds.

When the opportunity came to write for pay, it was, again, a matter of sheer chance. My bird-hunting buddy, who happened to be a small-town photographer, was asked to do a photographic essay for an outdoor magazine and the editor needed someone who could add a few words from a southern perspective. Despite the fact that he had never read a single word that I’d written, my pal volunteered me for the job, and we did the story together. And neither of us ever stopped.

I’m sure that I’ve mentioned it before, but I once read somewhere that if you want to take the measure of a man’s life, you should ask him to tell you his vision of heaven. I think the idea came from Gene Hill. The idea is that if a man’s vision contains a great measure of things from his current life, he is a very lucky man with a very good life.

I guess that describes me pretty well. Mine would be a reflection of the life that led me here. It would be filled with dogs and guns and wild, empty spaces and big skies and birds and time enough to wander. And maybe a small audience of friends to tell my tales to. That’s my world. And it’s hard to envision a way to improve on it.