The half-naked young man lay breathless inside the dark and dank beaver lodge, his legs and feet covered in cuts and scratches. He had narrowly escaped death after being captured by Blackfeet Indians while canoeing up the Jefferson River and had sought refuge in the tiny lodge.

The man was 35-year-old John Colter who was lying on his back on a cramped bed of tangled twigs and mud. As he stared into the inky blackness of the lodge, his thoughts went back to how he arrived at this unlikely sanctuary.

The year was 1809 and Colter had been canoeing up the Jefferson River when he and his companion, John Potts, had been ambushed by Blackfeet Indians. The two men had left Fort Raymond to seek out the friendly Crow Indians to establish a trade agreement.

At a narrow stretch of river, the men came under attack by Blackfeet hidden along the shore. The Indians had trained their guns along with bows and arrows on the men as they rounded a bend in the river. The Indians blocked their way and demanded that the men come ashore.

Colter agreed and waded to the bank where he was forced to strip naked. Potts refused and was immediately shot to death by a barrage of bullets. His body was then dragged ashore and hacked to pieces by the frenzied Indians in front of a horrified Colter. It was then that the naked Colter was ordered to run for his life.

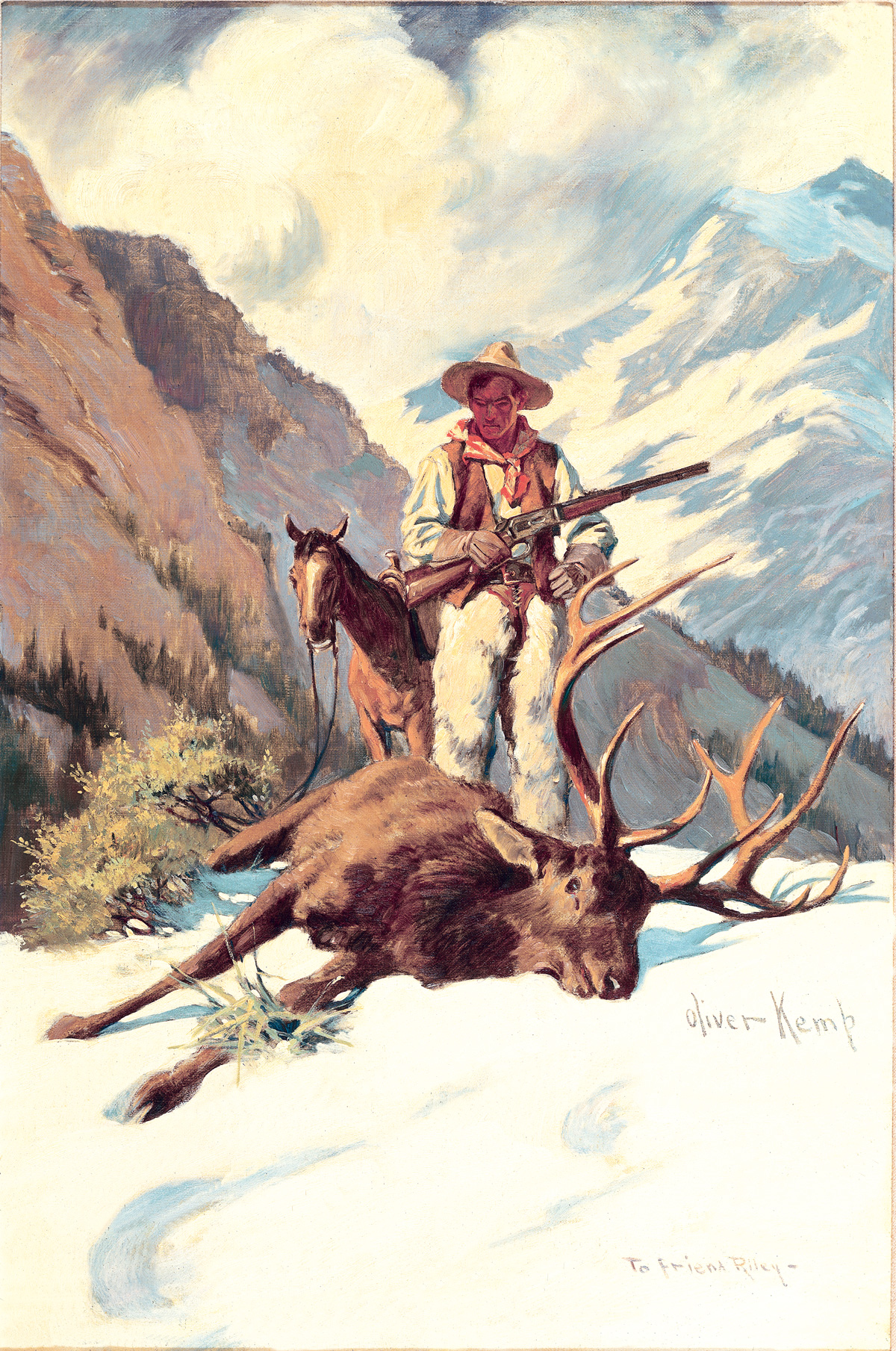

Wasting no time, the beaten and bleeding Colter made a run for it before the Blackfeet could get properly organized. He ran as fast as possible for many miles, severely cutting his feet and legs on the brushy terrain. Amazingly, the sure-footed Colter was able to increase the gap between him and his savage pursuers.

Eventually, Colter’s injuries began to slow him down and he noticed that one of the braves was gaining on him. The exhausted Colter suddenly stopped and turned to face the fast-approaching Indian.

As the brave came rushing at him with spear in hand, the bloodied Colter spread out his arms in defiance. Perhaps it was the shock of seeing the white naked apparition that caused the Indian to stumble and drop his spear, which broke when it struck the ground.

As the Indian fell, Colter dived for the spearhead, then jumped on top of the brave and stabbed him to death. Colter knew that the remainder of the Blackfeet were not far behind, so he grabbed a blanket from the dead Indian and continued his run.

After several miles, Colter noticed a beaver lodge on an island of mud and twigs in a large pond. He waded through waist-deep water to find the entrance then, holding his breath, dove underwater to enter the lodge. Sprawled across the beavers’ waste and leftovers, Colter could hear the Blackfeet searching for him nearby. He felt as though he was being eaten alive by the myriad fleas and other insects.

After a while, Colter could no longer hear the Indians and decided to make his escape. Cautiously he crept from his hiding place, then proceeded to walk 11 miles to a trader’s fort on the Little Big Horn and into the history books.

John Colter’s story really began six years earlier when he was recruited by Lewis and Clark to join their Expedition of Discovery.

Lewis was impressed with Colter’s outdoor skills and camp craft and, in October 1803, recruited him at the rank of private with a starting wage of five dollars per month. But Colter was a rebel and soon fell out of favor with Lewis when he was charged with threatening to shoot an officer.

After being court-martialed and confined to base camp, Colter was eventually reinstated after he apologized for the insurrection and promised to reform his ways. He went on to become one of the most valued members of the team and would emerge from the Expedition of Discovery as one of the most famous of the mountain men.

Besides being a skilled hunter, Colter was responsible for finding passage through the Rocky Mountains and was able to successfully barter with the many native Indian tribes he met along the way. Lewis was also impressed with how he was able to guide the Corps of Discovery down through the Bitterroot Mountains to the Snake and Columbia rivers, which enabled them to reach the Pacific Ocean.

In 1806, after traveling thousands of miles, Colter and the men of the corps returned to the Mandan villages in what is today North Dakota. That August, Lewis and Clark allowed Colter to be honorably discharged, some two months early, so he could guide two trappers back along the expedition’s route.

By departing early, Colter may well have forfeited his bonus pay for his work with the Corps of Discovery. However, Thomas Jefferson himself stepped up and praised Colter’s achievements, rewarding him with a special land grant and the $377.60 he was due.

As other members of the corps returned to their homes and loved ones, each man brimming with exciting tales of their journey, John Colter was heading back into the wilderness with two trappers, Forest Hancock and Joseph Dickson. They had a two-year supply of ammunition, 20 beaver traps as well as all the essential equipment used by mountain men.

The three men apparently did not get on well together and they split up after a couple of months. There is a possibility that Colter became restless and headed into present-day Wyoming to find better areas for trapping. In 1807, while he was trapping near the mouth of the Platte River, Colter met Manuel Lisa, owner of the Missouri Fur Trading Company. Lisa was leading a group of men who were once with the Lewis and Clark Expedition, some of whom were known to Colter. This chance meeting with John Potts, Peter Weiser and George Drouillard encouraged Colter to join his former companions and remain in the wilderness.

Colter went on to help build Fort Raymond near the confluence of the Yellowstone and Bighorn rivers. Later that year, he decided to leave the fort to search for a tribe of friendly Crow Indians with whom they could trade. In October 1807, Colter left the fort alone with a small pack along with his rifle and ammunition. This is where the “Legend of John Colter” really began.

After walking several hundreds of miles in the depth of winter, he returned to the fort the following spring with tales of bubbling mud pots and geysers of scalding water. Few believed his stories. His fellow mountain men and trappers at first made fun of him and referred to his tale as “Colter’s Hell.” John Potts had listened intently to Colter’s stories and was eager to see the geysers for himself, so once the weary Colter had recouped, it was agreed that, along with Potts, he would return to renegotiate trade agreements with the Indians.

In 1809, the two men left the fort and began canoeing up the Jefferson River toward the friendly Crow. It was on that expedition that John Potts would be savagely killed and Colter would make his now-famous “Run for his Life.”

He remained in Three Forks, Montana, until 1810 when, after the death of two more of his companions at the hands of the Blackfeet, he decided to quit his career as a mountain man and return to St Louis. That year he married a woman named Sallie, but it was only two years later that he is believed to have died of jaundice.