“I’m not trying to record history or paint from an historical perspective. I don’t particularly care about the rib on an over-under. I’m capturing a mood.”

If James B. Robinson wrote scores for movies, which he does as an offbeat hobby, the mix would be eclectic. Picture a little Bach wrapped around some rhythm and blues with country-western on the side. Robinson doesn’t like to be categorized in either his music, which is an avocation, or his art, which has been his vocation since 1970.

The artist.

Take Robinson’s All Clear; a painting in which the eye is inexorably drawn to a stately whitetail buck that is an integral part of a stunning central Texas landscape. Let the eye rove and it settles on a doe to the right of the buck. Robinson has created a whitetail painting that transcends the inherent appeal of the animals themselves. Here is a painting to be appreciated by anyone in touch with the rugged beauty of the Texas Hill Country or, for that matter, anyone who appreciates the lure of the outdoors, Texas or otherwise.

In All Clear, Robinson has created a wonderful landscape and placed the deer in it. The animals are the focal point but they no more dominate the scene than does the surrounding landscape. Each element is an integral part but none is dominant. To the artist, the mood is just as important as the animals.

Robinson is not a deer hunter, nor has he ever been. He has been, however, a duck hunter, and his interest in sporting art arose from pre-dawn boat rides through the shallow, grassy marshes of historic Barrow Ranch Hunting Preserve east of Houston. The intoxicating stench of marsh mud and the whistle of wings overhead created many a duck hunter but few artists as talented as Robinson.

Unlike many sporting artists, Robinson leaves much to the imagination. His style is loose and moody but any duck hunter who has been in the situation depicted in The Skeptics, instantly feels the thrill of iridescent feathers against a rose-colored sunset.

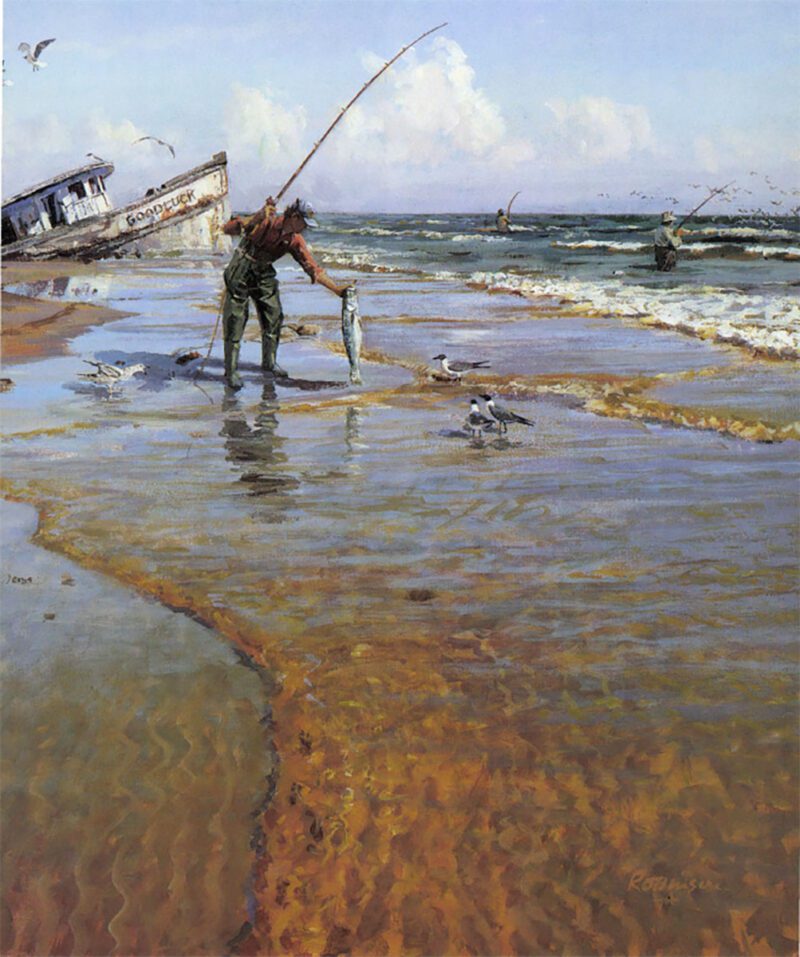

In The Liar, Jim Robinson painted water that looks wet — that seems to ebb and flow across the canvas.

“I’m not a detail person,” he says. “I hate it when critics point out some error in the way a shotgun looks in a painting or how a particular style of saddle wasn’t used in a specific area. I’m not trying to record history or paint from an historical perspective. I don’t particularly care about the rib on an over-under. I’m capturing a mood. To me, the feel of a scene surpasses the technical aspects of what the characters are wearing, how their guns look or how their dog is standing.”

Not only is Robinson a mood painter, he understands, in the classic style of Clint Eastwood’s Dirty Harry, that “a man’s gotta know his limitations.”

“I don’t have the portrait ability to make people dominate in my paintings,” he explains. “A painter must know his limitations just as a singer must know his. There are certain notes that some singers cannot hit, and there are elements in a painting that some artists do not handle well. I understand what I can and cannot paint.”

As early as elementary school days Robinson “sold” his art — like using it to prop up school reports that were weak on content. “I always did illustrations with my reports. My papers weren’t very good but the teachers seemed to like the art.”

Robinson’s All Clear is a landscape, not a portrait of two whitetails.

Robinson went the usual route artists take, combining art and music as his college major and entering the world of graphic design with Brown and Root, Inc. in Houston. His broad scope of experiences in commercial illustration and his Barrow Ranch duck hunting background provided an early foundation for his sporting art.

For a time he dabbled in duck hunting scenes, but lacked the confidence to promote his labors of love. Finally, J.C. Robinson gathered up one of his son’s better efforts and marched into Meredith Long’s gallery in Houston. Meredith Long, through his association with John P Cowan, popularized what has become a Southwest genre of sporting art, convincing a reluctant market that sporting art and fin e art were one and the same. Long liked what he saw on Robinson’s canvas.

“Since I knew ducks and geese and knew them well, that’s how I started,” recalls Robinson. “I branched out from waterfowl into paintings of coastal fishing. I also got into quail hunting, and that’s been one of my top-selling subjects.”

In The Skeptics, Robinson records the kind of memory that every waterfowler cherishes.

Like many Texas sporting artists, Robinson patterned his work after Jack Cowan. He unabashedly admits the Cowan influence. “I studied his work- in fact, that’s how I learned about the elements of a quail hunting painting. I hadn’t done much quail hunting. After studying Cowan’s work, I learned that he was different than any of the others. He had, and still has, a recognizable style that separates him from other sporting artists.

“When Cowan came along, nobody else had done Texas quail hunting. All the quail scenes were of Old South plantations. Texas is much different. Cowan blazed new trails and everyone else jumped on the bandwagon. While I have learned from his groundbreaking work in this art form, I feel that I have been successful in retaining my own personal style.”

Over the years Robinson’s paintings have been handled by Meredith Long, Meinhard Galleries in Houston, and Collector’s Covey in Dallas. Currently, he is the featured artist at Story Sloane’s Art Gallery in Houston.

Approaching Storm typifies the artist’s impressionistic style.

“Jim’s versatility is what separates him from other artists,” says Story Sloane III. “We’ve always admired his style. His hunting and fishing scenes are really exquisite landscapes that include the sporting element somewhere within them. The painting style is loose and yet, when viewed from the proper distance, the elements are as clear as if they were photographed.

“Most sporting artists get locked into a formula, and that’s what they paint, time and time again. Jim has chosen not to be stereotyped. When he branched out into landscapes and Western art, they sold just as well for us as his sporting scenes.”

Robinson spent his latter Houston years watching cars blast by on the Southwest Freeway When the traffic became so bad that gridlock began forming each day at 6a.m., he decided it was time for a change, so he moved his family to a suburb in north Austin.

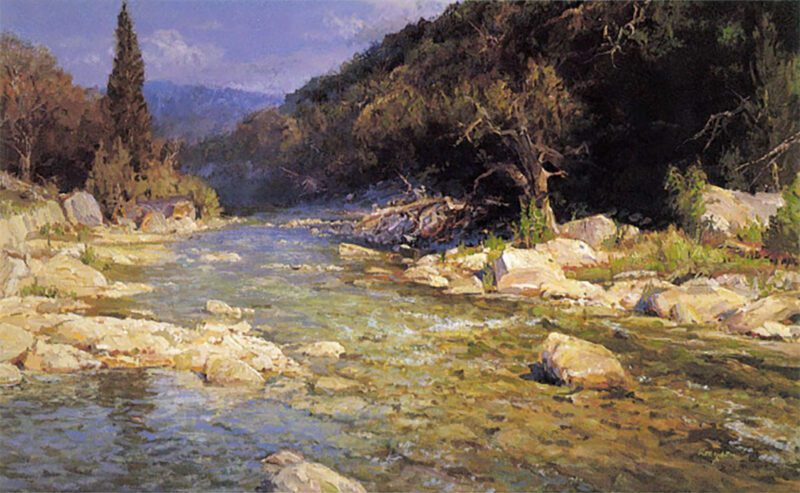

One of the prettiest Texas cities, Austin is situated on the edge of Hill Country Within minutes of his home, Robinson can be hiking rocky trails or photographing limestone hills studded with ancient live oaks. In the 10 years he has lived near Austin, virtually every scenic locale that’s readily accessible has shown up as background for one of his paintings.

A dramatic play of light heightens the feeling of excitement in Robinson s acrylic, In The Bag.

“I take tons of photos, and I often refer to a photograph when I’m trying to visualize a setting for a new painting. I may use the same setting repeatedly but I don’t worry much about it. It looks different every time I paint it. I may add some vegetation or take away some vegetation. The mood changes as well with the shifting light between morning and afternoon.”

If there is anyone trademark of Robinson’s art, it is his dramatic use of light. “For me, using bold, strong lighting and values are the best ways to convey a dramatic situation. My sporting scenes invariably reflect those times early or late in the day, which means greater contrast between light and shadow and more intense colors. Of course, fish and game are most active during these periods, which is all the more meaningful to the sportsman.”

Robinson prefers subject matter that he knows and understands. That’s why his settings seldom venture beyond the vast Texas borders. And with its ten distinct ecological regions, the Texas landscape offers the diversity of several states rolled into one.

“There’s a danger with becoming known for a certain subject. People see that work and they like it, and that’s what they expect you to do. The one thing I cannot stand is to get in a rut. I like all kinds of art and subjects. I must have diversity. That’s my nature. I like too damn many things to allow myself to be pigeonholed into a particular formula or subject.”

His favorite sporting subject is coastal fishing, particularly surf fishing. The elements of breaking waves, big fish, coastal cloud formations, seagulls and shipwrecks combine to provide a dramatic and compelling image. The Liar, Last Sandbar and Heaven (see cover) incorporate most or all those elements.

Whether a painting of surf fishermen or goose hunters, there’s usually water somewhere in the scene. “Jim once told me that water was one of the easiest things for him to paint,” says Story Sloane, “yet he paints it with a degree of quality and clarity that, in my experience, is unmatched by any other artist. In The Liar, for example, the water along shore is transparent, except for the faint reflections of clouds. That kind of effect is very difficult to achieve.

“Jim’s ability to paint water has made his work especially popular with fishermen. He did two membership prints for the Gulf Coast Conservation Association — both of surf-fishing — and they sold remarkable well.”

Texas Style captures that chaotic moment when geese pour into the decoys from different directions.

Not a field person by nature, Robinson is content to live in a subdivision on the edge of Austin, close to good schools and shopping malls. His imagination and artist’s eye are so keen, however, that he doesn’t need to immerse himself in picturesque settings. He often spots interesting cloud formations while driving into town to see a movie. Or, it may be the play of light on an ancient oak tree near home.

Robinson is a loner who sometimes wishes art was not such a lonely endeavor. He enjoys talking shop with other artists, especially longtime friend and artist Bob Wygant. They are apt to discuss painting technique rather than ducks or fish.

“I’m inspired by talking with other artists and seeing their work. Bob and I often talk about our problems on specific works. It’s a constant learning experience.”

Robinson works at home, in a bedroom converted into a modest gallery For a while, he kept an office and gallery separate from his home but so many people stopped by to visit that he couldn’t get much work done.

When Robinson hits a snag while painting, he sets the piece aside and concentrates on another. He typically has several paintings going at any given time, and they often span his interests. That way, if he gets tired of a landscape, he can work on quail hunters or cowboys for a while. In the background, a tape softly plays music, usually pure classical, though possibly one of the 300 or so musicals he has on tape.

Robinson used to paint around the clock, seven days a week for months on end, but now he works about eight to 10 hours most days and only is the most productive when the mood strikes him. He also teaches painting workshops in which he tries to help students learn more than merely how to slap paint on canvas and make it look recognizable.

An old windmill and gnarly thickets of mesquite add a sense of place to They Kept Coming, one of many Texas

quail-hunting scenes by the talented artist.

“I’m an old believer in training, and I think it’s very important for young artists to take courses in such things as design and drawing. A lot of people pick up a brush and jump right in, never learning what art is really all about. A knowledge of art history is also important, so they can learn the styles and techniques of other painters and come to understand what they’re trying to achieve. Studying non-objective and abstract art may seem like a waste of time to the young wildlife artist, but the same fundamentals at work in abstract paintings apply in impressionistic and realistic art.

“I would like not only artists, but also patrons to have a better understanding of art. Art is not a mere representation of a subject but rather a feeling. People look at a painting and all they know is that they like it. They don’t know why they like it. I’d like for them to understand just what it is about a painting that makes it special.”

Robinson accepts commissions on just about any subject matter, but adds: “If buyers would let painters do their thing without too much input, they would get better art. If you influence an artist too much, you don’t have his work at all — you have someone else’s work.”

It is unlikely that Jim Robinson’s patrons will have that problem. A dramatic impressionist who refuses to be categorized, he remains as moody as a Texas coastal sky, as unpredictable as mallards riding a norther’, and as independent as a big-running pointer.

And when you really think about it, isn’t that the perfect definition of artist.

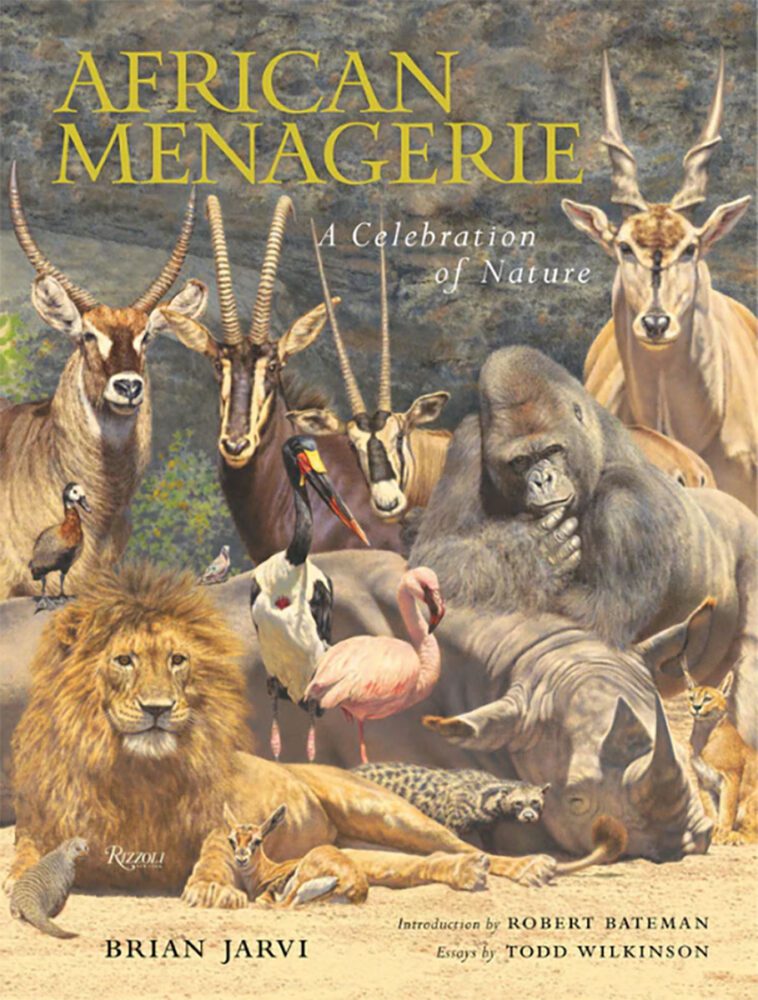

Depicting more than 220 African species, the stunning large-scale mural African Menagerie is artist Brian Jarvi’s masterwork. Lavishly reproduced in an oversize format with a gatefold, this book brings this landscape masterpiece to the conservationist, lover of Africa, and fan of wildlife art. In oversized color reproductions, the book African Menagerie offers readers a look at the finer details of the realist renderings of the animals and birds across the seven panels and thirty feet. There are also reproductions of the animal studies Jarvi created in the seventeen years leading up to the final work. Buy Now

Depicting more than 220 African species, the stunning large-scale mural African Menagerie is artist Brian Jarvi’s masterwork. Lavishly reproduced in an oversize format with a gatefold, this book brings this landscape masterpiece to the conservationist, lover of Africa, and fan of wildlife art. In oversized color reproductions, the book African Menagerie offers readers a look at the finer details of the realist renderings of the animals and birds across the seven panels and thirty feet. There are also reproductions of the animal studies Jarvi created in the seventeen years leading up to the final work. Buy Now