Ninety years ago, a group of sportsmen agreed to build a private hunting lodge near the banks of the Santee River in the South Carolina Lowcountry. As evidenced by the records, photos and trophies regaling the walls, a grand old time was had by all.

“Good shooting in scattered pines and sedge in afternoons. Asheville dogs unable to find birds in mornings. Birds plentiful but coveys scattered. Rain Sunday night but ground dry. Fox race Monday night. Deer seen in Pines northeast of lodge. 1 owl.” — December 26th, 1931

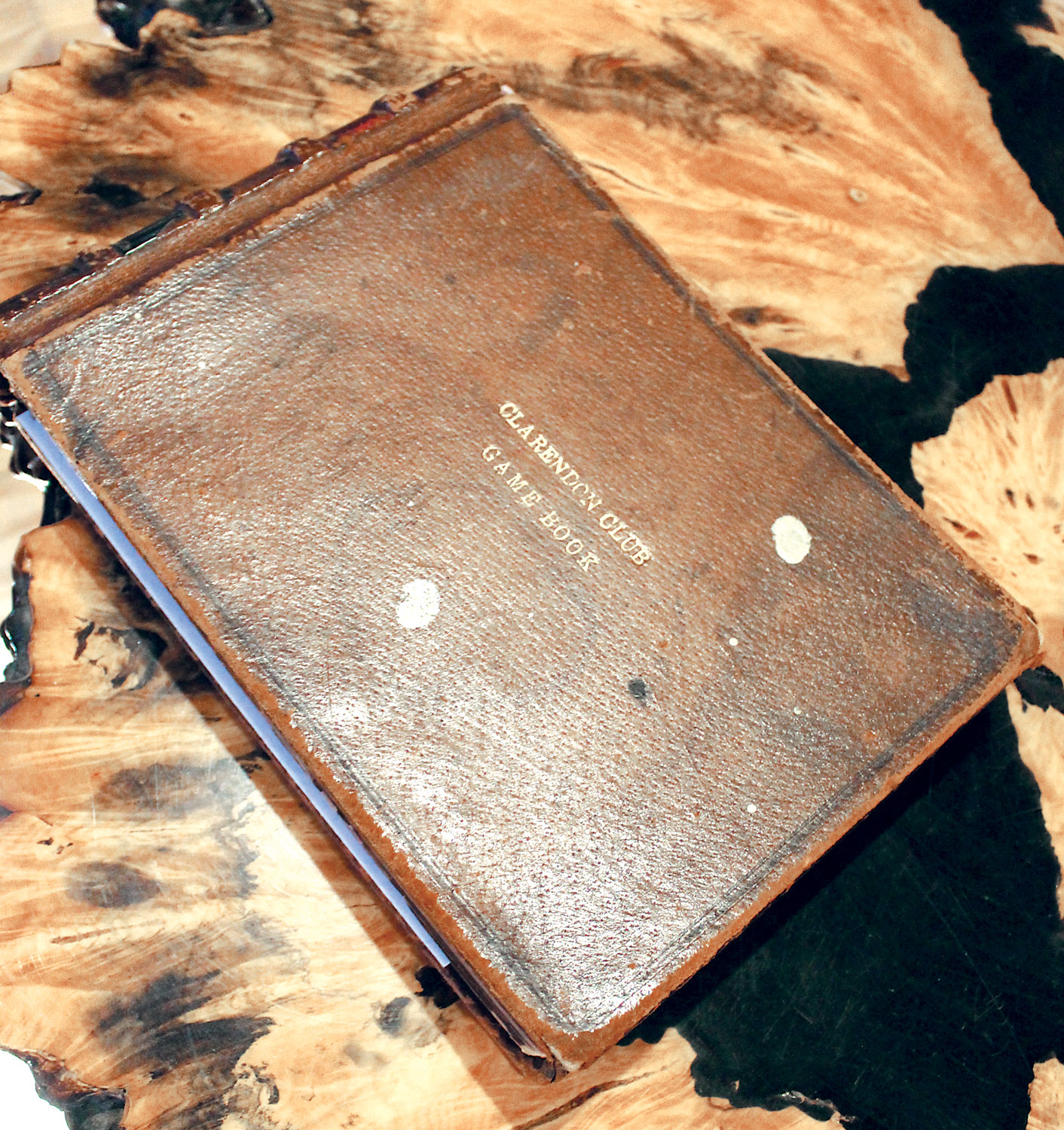

It’s is one of the earliest entries in the Clarendon Club logbook. The archive still sits on an ancient cypress coffee table in the club’s office where Trey and Whitney Phillips are pouring their hearts into bringing a classic old Southern hunt club back to life.

“If you look through the records, you see they hunted deer, quail, rabbits…even owls,” Whitney said with a smile. “There weren’t really any regulations back then.”

When the Santee dam was completed in 1941 as part of the rural electrification program, much of the original club land lay under water. The rest became part of the Santee National Wildlife Refuge. However, the club was grandfathered in, and members were allowed to hunt any of their original property that was still high and dry.

Whitney wasn’t sure of the date, but at some point in the late 1940s or early ’50s, the clubhouse burned to the ground. That was considered by most as the last hurrah for the club. But shortly after, Ralph Cuthbertson, a frequent visitor and nearby landowner, rebuilt the structure. By 1974 the Clarendon Club was up and running again.

Ralph’s wife and daughters ran the day-to-day operations of the club, while his sons moved to Greenville to work with an aviation company. There, they began flying clients down to the club, entertaining them with superb hunting, fishing and Southern hospitality.

“Eventually, the Cuthbertson’s all moved back to the Upstate,” Whitney continued. “But there are still a lot of families around here who were involved in some way with Clarendon Club, and they share stories about their times here, like using flashlights to guide the airplanes in for night arrivals on the grass landing strip. One of the more famous guests was Hugh Hefner. He made several visits.”

Whitney said a lot of the people who were part of the club, or their families, still live in the area and still talk about the history of the club.

“It’s been fun to sort of liven things up again and get the folks excited,” she continued. “They want to tell stories about their time here or show old photographs. I love that sort of thing, because I’m kind of a history nerd.”

After the Cuthbertson’s departed, there was a short-term owner of the lodge, Chris Carson, a builder from nearby Daniel Island. Chris did a lot of the construction, including a pavilion, but still, the club was nothing like it had been in the 1930s and ’40s.

Then, in 2018, it was all purchased by Trey and Whitney. Trey is a pharmacist in the town of Summerton, and the couple has expended a lot of energy in reviving Clarendon Club.

Along with raising two kids, they’re putting their money, time and additional property into the place to return it to its glory days as a classic sportsman’s getaway. Those activities include deer and duck hunting, bass fishing in their stocked ponds, and striper, catfish, crappie and bass fishing in nearby Lake Marion.

They also have golf packages with Santee National Golf Club just ten minutes away.

For the deer hunter, there are plenty of treestands and ground blinds on large, well-kept food plots cut in between hardwood swamps and stands of pine. Overall, the mixed habitat is ideal for the plentiful whitetails.

“There weren’t as many deer back when they started,” Whitney told me. “Not like there are today. You might see a note in the book, ‘hunted for three days, jumped one or two does. Had awesome time.’

“That’s all they had, but they all had a great time. Back then, it wasn’t about killing in mass numbers, but about enjoying the hunt. And that’s how it should be, really.”

If duck hunting is in your blood, their impoundments of flooded corn, sorghum and millet draw most all the eastern flyway species, including blue- and green-winged teal, wigeons, mallards, pintails, shovelers and ring-necks. LOTS of ring-necks.

I had the opportunity to hunt waterfowl at Clarendon Club in early January. There are several four-man blinds in their three impoundments, and I shared a box with Eric Doyle, Brian Richardson and his son, Walker.

We all had chest waders, shotguns, shells, calls and flashlights. Eric floated the bag of dekes out, while I carefully held my camera high, wobbling through the mud with every step, terrified I was going to tip over and soak my old Remington 870 or, worse yet, my Canon EOS camera. But we all made it to the blind with no mishaps.

The blind was roomy and well camouflaged, and we all scrunched down in anticipation of that heavenly sound of quacks, whistles and beating wings. Light was just breaking to the east, and the decoy set was gradually illuminating.

There was little to no wind, so the plastic mallards the guys set out sat like little statues — not the best situation for attracting real birds. Regardless, we all stared expectantly into the steadily glowing sky.

Then the 13-year-old Walker whispered, “ring-necks.” I couldn’t see them, but his youthful eyes were much sharper than mine. Then I heard the whistles. The ringers were way up there. But they were there.

Walker is an interesting and inspiring story in himself. At the age of five, he was diagnosed with leukemia. For the next three and a half years he and his parents battled the disease, traveling from their home in Aynor, South Carolina, to a hospital in Columbia, some two hours away. Finally, at age ten, he was declared cancer-free.

Walker developed a love of hunting and fishing during his treatment years, and now that he’s healthy, he has become a consummate outdoorsman. He had a full string of duck calls and knew how to work them all. A good shot too.

“My boy enjoyed it, and that’s what it was all about for me,” his dad would tell me later.

Just after shooting light, a pair of mallards buzzed by. A couple of shots were fired, but not a feather was cut. No problem. There were more birds. Lots more birds.

Shortly, shotguns were popping in the other two blinds and above us the ring-necks swirled way out of range.

At last the wind kicked up and our decoys began dancing. The sun was throwing orange and golden light across the water and highlighting the hundreds of ring-necks circling closer.

Enough mallards had landed safely in the middle of the pond, away from the blinds, that most of their kind were heading straight for the noisy, splashing flock a hundred yards away. Still, a few came our way, and we made some good shots.

While shotguns blazed away, I spent most of my time shooting pictures. But I, as did everyone in the blind, eventually burned a box of shells. By 10 a.m., we were all out of ammo, while the birds continued buzzing by for a look-see.

For me, it’s always refreshing to visit South Carolina’s historic Lowcountry. There, things move a bit slower, except for those ring-necks. Speedy little divers!

“We want people to enjoy whatever their favorite outdoors activity happens to be,” Whitney said. “Whether its hunting, fishing, skeet shooting…. We may not offer it every day, but we can make it happen. We’re very flexible. Whether it’s a one-day hunt for deer, or a large group that wants the red carpet, we can oblige.”