He stood alert and calm, feet close together, gun forward in position of easy readiness, his left hand well out under the barrels. Then he saw the bird, and the gun moved in that clean, smooth swing for which he was noted. But this time, part way through the motion, there was a jerk of uncertain co-ordination. He fired twice, and kept turning away from me as he followed the bird’s flight. He had missed again!

Stiffly, as though his legs hurt, he walked to an old apple tree and leaned against it. I scrambled over the stone wall and broke through the blackberry briars that separated us. Dad smiled. He opened his gun and removed the smoking shells — but he did not reload.

“It’s my legs, Jimmy. They’re tired — dead tired. They ache.”

“But, Dad —“

The wind stirred a lock of silver-white hair that curled below his hat brim: “Don’t get excited. It’s nothing but what most old Fellows get. It’s rheumatism.” This tall, fine-eyed man to whom I belonged; who had taught me grouse and wildfowl shooting; who had held my wrist while I caught my first trout; who had taught me to walk; this man — my father — was suddenly gone old before me, white-haired, sunken cheeked, and 70! ”Why — Dad!”

He leaned heavily on a low limb, taking the weight off his legs. “Hush-hush, now. It’s nothing at all.”

I had to help him home. He wouldn’t go the shortcut — afraid someone would see him leaning on me, or see the muscles of his face drawn taut with pain. We went by Blanchard’s wood road and up Hickory Lane along the marshes. The only person we saw was one of the Tibido children, a hungry, tousle-headed urchin of seven — barefooted, the first of November!

Dad never let on he had seen the child until I got him home and into his chair. Then he said: “I’m afraid we wont be able to do much for the Tibidos this Christmas.”

Already Dad had begun to think of that!

I can remember as many as 30 of us around the long dinner table: Grandfather always carved the game which Dad and my older brothers had shot for the occasion. Grandfather would say: “Henry (that’s Dad), is this knife as sharp as you can get it? Dad would say “Yes, sir” but grandfather would pick up the steel and whet away for five minutes while our mouths watered. “There now, I guess we’re ready,” he’d finally remark, and plunge the knife into the breast of the roast goose or black duck, peering critically at the issuing juices to determine if the bird was properly done. Invariably it was. So grandfather would part his whiskers with practiced accuracy and say: “A-h-h-h!” and of course the women folk would all congratulate one another on their cooking.

I can remember as many as 30 of us around the long dinner table: Grandfather always carved the game which Dad and my older brothers had shot for the occasion. Grandfather would say: “Henry (that’s Dad), is this knife as sharp as you can get it? Dad would say “Yes, sir” but grandfather would pick up the steel and whet away for five minutes while our mouths watered. “There now, I guess we’re ready,” he’d finally remark, and plunge the knife into the breast of the roast goose or black duck, peering critically at the issuing juices to determine if the bird was properly done. Invariably it was. So grandfather would part his whiskers with practiced accuracy and say: “A-h-h-h!” and of course the women folk would all congratulate one another on their cooking.

Cranberry sauce, four vegetables, a sideboard creaking under its burden of assorted pies, cakes, fruits — and cider pitchers.

At Christmas dinner, the pièce de résistance was game — traditionally shot by members of the Osborn family. But the real ceremony, the welding of the Christmas spirit, came on Christmas Eve. That was Mother’s. Every year she went down to the Tibido’s shanty laden with baskets of food, the rest of us following with presents for the children. The Tibido children worshipped Mother. She gave because she loved to give, and they knew it.

After supper, at home, we sang Hark, the Herald Angels, Holy Night and Little Town of Bethlehem — accompanied by Uncle Alden on the melodeon. Then we gathered by the fire while Mother read Dickens’ Christmas Carol aloud. That was the final rite, and it seemed to bind us all inseparably.

She read by candlelight, and by the glow from the fire — tipping the book just a trifle to catch its light. Invariably she began with the same words, spoken in the same reverent voice: “WeIl, children — this is A Christmas Carol, by Charles Dickens.” Mother had read that moving masterpiece each Christmas since I was old enough to listen. I think I could recite it all from memory.

Firelight! Marley’s ghost rattling its chains while children listened in wide-eyed wonder. Once Uncle Alden went to sleep and snored. And once grandfather became so enraged over Scrooge’s stinginess that he rose from his chair, thumping with his cane and growling through his whiskers, I’ll pound that fellow to a pulp!” Nearly everyone was moist-eyed with sympathy for Bob Cratchit and Tiny Tim. You would see a handkerchief whisking upward now and then. On the rug, as close to the fire as they could get, slept our three foxhounds — Moby, Belle and Trailer. They twitched, concerned only with their dreams of primitive triumphs.

Most of all, I remember the expression in my father’s eyes. This was his day of days. I can only guess at his deep, inarticulate happiness. Under those smoky, hand-hewn beams his family had grown, branched and matured. Devotion to its meaning, and gratitude for its unity and goodness, overflowed his heart and shone from the depths of his eyes. The Christmas Eve reunion was, I think, a reward for his renowned generosity.

Then, bit by bit, the reward diminished. First the War, and my two brothers lost. My sisters married and moved away. One by one the rooms were vacated, rooms from which for generations we had watched the seasons ebb and flow. Then Mother died — and this was to be our first Christmas without her.

The Tibido urchin had reminded Dad too abruptly of this. I could almost feel the hurt of his thoughts: the Osborn tradition washed up. Nothing left but an album full of tintypes, a basket of last year’s tree decorations and a sheaf of newspaper clippings describing the liquidation of the Osborn cordage business. One of those clippings said: Henry Osborn to settle 100 cents on the dollar. Dad did. He would. It left him almost nothing.

“No,” I said to him now, “guess we can’t help the Tibidos this year.” Impetuously, I added: “Why don’t you sell the old place? It’s too big for us — now.”

He looked at me with a slow faraway smile. The tiny wrinkles gathered at the comers of his eyes. “No, we can fill it Jimmy.”

For days I could hear his voice saying that. Then the sound dimmed in the harsh practical clatter of my young and struggling business. By the 23rd of December I had forgotten what Dad said. I shouldn’t have, for it was evidence of the strange hope within him. On the night of the 23rd, I bought a dressed turkey from the market, and subsequently worked late in my office over a stack of bungled invoices. I bought that turkey because a submerged intuition hinted that Christmas dinner of wild game — for Dad and me, alone —would be like salting a wound. I went home late, feeling pretty grim.

In the inky dark of the front hall I stumbled over something, and switched on the light. There, arranged with patience and precision, was my duck hunting outfit. Not a detail was lacking, because it was laid out by an old master. Two dozen black duck decoys, tarred lines neatly wound and tied, anchor weights in perfect shape; hat, gunning coat, sweater, boots and gloves; Uncle Alden’s historic old double guns; a box of chilled sixes; my duck call; a water bottle and box of sandwiches; row locks and oars — everything. On the table was the boathouse key and under the key a note:

“Be sure to hunt down all Cripples. Lead ’em plenty.

“Don’t use the duck call too much. Set out at Brick Oven Creek — and bring home the Osborn Christmas dinner! Good luck and good night. Your father.”

Oh, time-honored advice — and between its matter-of-fact lines, my father’s hunger to carry on a tradition through me! It wrung my heart. The first thing I did was to hide that turkey in the cold shed. If Brick Oven Creek failed to produce, I could always rediscover the turkey. But my prayers to the red gods were for black duck.

Morning on the marsh: A thin arm of red reached down the East, a shaft in a lead gray sky. Gulls wheeled in, a wanting from the open sea. Crows pitched and tumbled in the gusts. The ragged waves followed fast upon each other, and all of them bared their teeth in the salt wind which stung my eyelids.

Ghostly to be sitting there in the old blind at the mouth of Brick Oven! Forty years ago, Dad’s two brothers had built it of cedar stakes, wire and marsh thatch. Here, with the very gun I hugged across my chest, Uncle Alden had brought down three geese. Uncle Jim, for whom I was named, had rowed home from this blind with a mixed bag about which, after 30 years, the natives still speak. I had shot my first duck from this very set-out, father beside me to temper my 10-year-old excitement.

Abruptly now, through the swirling snowflakes, five blacks whipped down, their feet braced and wings set to the wind for landing. They nearly caught me reminiscing, but I dropped the farthest one and that gave me time to swing onto the nearest one as he flared. I doubled.

By the time I had pulled the grab from the mud flat and launched the skiff, the downed birds had vanished. Wind and snow made a bad business of retrieving. I ought to get a spaniel. When I located the birds, I was about half lost. I knew the wind direction, but had to guess at the angle back to the creek mouth. It was blind rowing, the snow thick and stinging. I never felt more lonely in my life, but I got back to my blind, bringing the foundation of the Osborn Christmas dinner. Two fat red legs — northern blacks, down from the sub-arctic.

I cannot explain the scarcity of ducks that day of traditional duck hunters’ weather-wind, cold, snow. Perhaps the birds had taken refuge in the fresh water ponds, inland. Once I started up, trembling to the call of wild geese, a big flock lost in the whirlpools of the sky. But I never saw them, and their weird, forlorn honking grew inaudible as they searched for haven.

At two o’clock, as the abnormally hightide started to ebb, I got another chance. Low to the water, a red leg came racing straight down the creek, the gale on his beam. My first barrel was 10 feet over him. The second connected while the bird was almost stationary, beating back against the wind.

My last chance was the one which got me into trouble. A pair whistled over from behind me — just luck that I saw them at all. I got one of them by remembering to hold well under. The bird crumpled, but from then on the snow swallowed it. I merely guessed as to where it struck the water. Four birds, past three o’clock, and getting dark fast. Marking the direction of the fallen bird, I hastily took in the set, tossed the blocks into the skiff and shoved off.

I rowed steadily for 10 minutes, counting myself lucky to find the bird. Then, in my mind, I fumbled for the direction home, and I felt as if I were the last man on earth. I couldn’t see 30 yards in any direction, and the weird curlicues in the water overside told of a raging tide lip. That, added to 10 minutes hard rowing and a northeast gale —all moving in the same direction — had me bewildered on the matter of distance. I guessed myself over a mile from the Brick Oven blind and pulled cross-tide for shore. I figured to make land between Martin’s Slough and the Town Bridge and pulled for an hour until it was black dark. You couldn’t tell whether you were two yards or two miles from shore.

I stopped rowing and listened, but I could hear nothing above the wind. It was like being marooned on a cloud at midnight, and on every hand I felt the turbulence of the sky. I was properly scared when, suddenly, an oar touched bottom, and an instant later the boat beached violently.

I didn’t have the faintest notion where I was, and this taught me something about being lost. You can plant your feet on ground you’ve trod since boyhood — and you won’t recognize it! I saw a light, and after hauling up the skiff, picked up my four birds and headed toward it uncertainly. I was pretty well fagged, dazed by the wind, my face like chilled putty. I actually knocked on the door of that lighted house before I recognized it — the Tibido’s poverty-stricken home! I was two miles off course!

From inside an excited child’s voice cried out at my knock, her irony all unwitting: “It’s Santy Claus! Santy Claus! Oh, mother! Open the door quick!”

Mrs. Tibido opened the door and I stumbled into the close warmth of the little kitchen. For speaking purposes my lips were useless, but I managed a gum-rubber smile for the circle of rapt expectant faces, young and old. Mrs. Tibido wiped her hands on her apron, and offered me one of them. I took the thin fingers in mine.

“We knew you’d come!” she said, happily. “All day the children have been expecting you, Mr. Jimmy.”

“Merry Christmas,” I mumbled.

That rather broke the ice, and the children rallied around tugging at me and begging me to come and see their Christmas tree. It would have cut you like a rusty knife! A spruce bush stuck in a cracked flowerpot with white grocer’s twine doing double duty as tinsel and snow. I shook some real snow off my hat onto the “tree.” It glistened briefly, and the children’s eyes danced.

You know what I did, of course. It was an impulse, I suppose — but it was a Christmas impulse. Anyone would have done the same thing. And it did add its mite toward perpetuating a tradition that mankind holds sacred — I mean the Christmas tradition. I left the four black ducks behind, and went my weary way homeward! The Tibidos totaled seven, counting their mauled kitten. The four ducks would assure them all of plenty. And Dad and I could have the turkey I had hidden in the cold shed. It was a fine plump turkey, and even though it wasn’t bagged by one of the two remaining Osborns, it would taste good to them. I made a rather bad job of whistling through chapped lips.

Dad was out somewhere when I got home, so I took a hot shower and gradually came back to life. I shaved and dressed and got downstairs just as Dad came in the front door. He was leaning heavily on his cane, but the eagerness in his eyes was jovially apparent. He wanted to know all about my duck hunt.

“Come on,” he insisted. “Out with it!” I described each detail, each bird, the look and feel and smell of the marsh. I told him of getting lost in the storm. He was thirsty for every last drop of description. He sat gazing into the fire, his lips wrinkling with his own reminiscences. “Good!” he said, quietly. “It’s good fora man to come face to face with the elements. It gives him respect for them, and for himself. Let’s see the ducks.”

I had been so long expecting that demand, that when the words actually came, I almost dodged. Just how could I explain the missing ducks, the even graver matter of the forbidden turkey in the cold shed — in the face of my father’s intense eagerness?

“Well, Dad,” I started, haltingly, “I bought a turkey yesterday. But when I got home late last night to find you had laid out my shooting gear, I knew you’d rather it was black ducks — for old time’s sake, shot by an Osborn. So I hid the turkey, Dad — like a thief hiding loot. Then, tonight, when I saw the Tibidos, and the kids’ Christmas tree, something got hold of me. I — I thought of Mother, and you, and other Christmases, and they all lumped together inside of me. But anyway, we’ve got that turkey, Dad.”

It was a solemn moment for me, that Christmas Eve.

So when father started to chuckle, then burst abruptly into laughter, I was a little confused and disturbed. But I think he divested himself of 15 years during that laugh, the first truly good one I had heard from him since Mother’s death. It came right from the deep part of him.

He got his cane, and, still chuckling, went to the sideboard for the decanter and two small glasses. He filled the glasses and handed me one, lifting his own to his lips: “Here’s to our Christmas, and to the Tibido’s Christmas. They’ve got the ducks — and the turkey! God bless them, every one!”

‘What turkey?” I asked, stupidly.

“The turkey! I was rummaging in the cold shed this morning, and found it .I’ve just come from the Tibido’s now. I gave it to them!”

“But they wouldn’t take both,” I cried, half angrily.

“Of course they wouldn’t. They didn’t know. And I didn’t know you gave them the ducks — not until after I’d given them the basket. I had wrapped the turkey so they couldn’t tell what it was, just as Mother always did,””

Oh, Dad! If Mother were only hereto share this with us!” I said, and I could have bitten out my tongue! Dad just nodded. He was thinking, too, that it was the sort of thing she’d appreciate.

That Christmas Eve had a kind of solemn splendor to it. Father and I were happy in a strange, moving way. The evening had a rare quality which makes your heart glad, and makes your throat hurt, too, Mine was glad when Dad said: “We’ll have ham and eggs for Christmas dinner. In this instance, finer even than turkey or black duck!” And my throat hurt when, after lighting the candles, he sat in Mother’s chair by the fire; when he reached up and took the book from the wall cupboard; when he opened it, leaning just a trifle to catch the light; when he looked up once at the emptiness of the great room, at the smoky hand-hewn beams, and at the memories that dwelt forever in those shadows. My throat hurt unbearably when he looked into the fire, and began: “Well, children — Jimmy — this is A Christmas Carol, by Charles Dickens…”

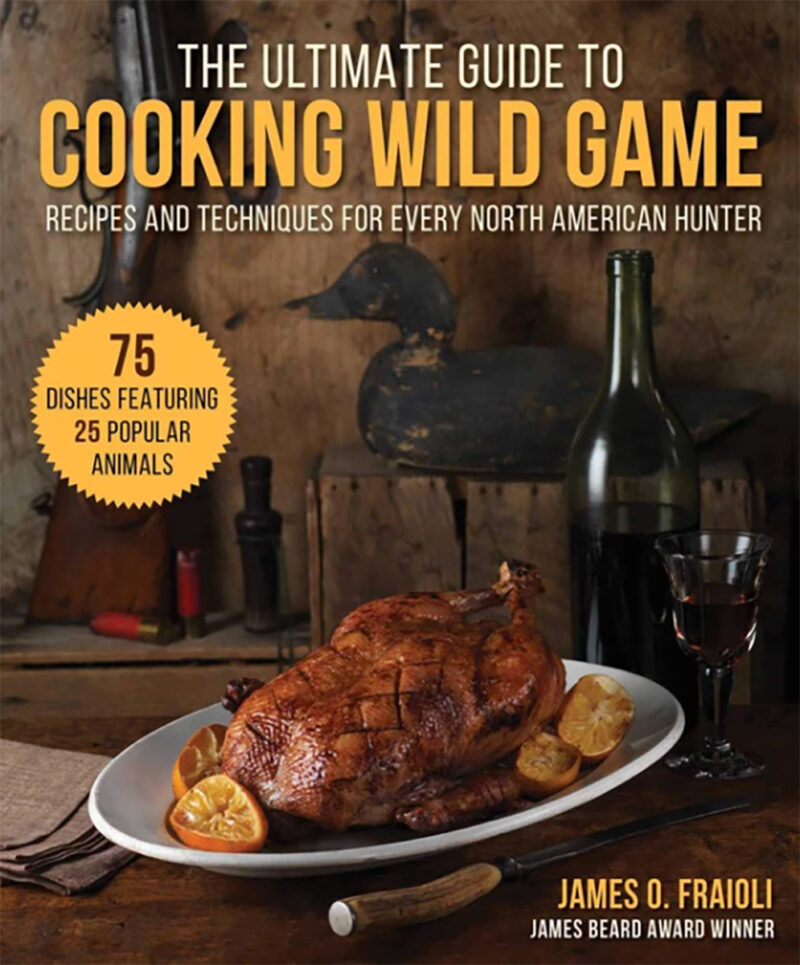

Recipes and techniques for every North American hunter. The new go-to cookbook for wild game hunters in the USA!

Recipes and techniques for every North American hunter. The new go-to cookbook for wild game hunters in the USA!

Wild game also has the edge when it comes to flavor, and with that delectable flavor comes the benefits of essential fats like omega-6 and omega-3, which are critical components of a healthy diet. Enjoy seventy-five simple and delicious recipes for cooking the wild game through the recipes featured in this book. Buy Now