. . . It all happened so quickly.

Suffice it to say that it was the smaller, younger bear who had shown up first on the dense, dusky trail ten yards away in northern Ontario, with the big bear in close pursuit just a few yards behind, intent on murder. And now, all I know for certain is that when it was all over, the old scar-faced boar lay dead at my feet and I was a couple of lifetimes older and the younger bear was long gone and left to speculate about what had just happened in his wake.

Anyhow, 25 years later, I’m still trying to put it all together.

I awoke in my cabin the next morning to a cold steady rain, following a long night of fitful dreams. But soon the rain passed and the sun appeared, and after I had thoroughly scraped and salted the old boar’s thick, grizzled hide and his meat was safely in the cooler, I meant to return to the scene and try to find and retrieve my spent shell casings and then backtrack him to see where he’d come from.

I carried no rifle, only my camera and ax, as I slipped through the cool, sun-dappled springtime woods. It was thick and verdant, with new growth everywhere except for one small, open glade that skirted a bog a few hundred yards from where I had killed him. And as I stepped into its edge, I suddenly caught movement to my right.

It was a ruffed grouse, standing less than 30 yards distant on the stony edge of the clearing and slightly above me. Her head was up, her comb erect, her dark eyes wide and alert with two tiny glints of fear and anger reflecting from them as she alternately looked from side-to-side and then at me.

I puzzled for a moment, wondering why she did not flee. Then I saw them, two tiny balls of fluff scurrying from her into the dense brush to my right, then two more scuttling across the rocky ground to the left, and even more retreating into the woods behind her.

Quickly I understood: I had surprised her and her brood as they fed there in the edge of the clearing, most likely on the tender young shoots of clover and the protein-rich bugs that had come out with the morning sun, and I dropped to the ground in hopes of diminishing the perceived threat in her mind, lest she forsake her family and fly.

Oh, the foibles of youth! She had tried so diligently to teach them, had done the best she could. But now in their moment of crisis, her babes had split up and left her alone, and she had some tough choices to make. Which ones should she follow? Which ones should she forsake? Should she stay and fight, or should she fly and save herself, and then hope for another, more well-behaved brood somewhere far out in a vague and uncertain future.

In her mind, if she stayed to gather them or tried to defend them from whatever this was that had just appeared, she would surely die. But then, why should she not die for them? Would I not die for my children? Would you not die for yours, as God once died for His? Is death not sometimes required for life to grow, and is Life not a worthwhile price to pay? It certainly seemed to be for her on this fine Canadian morning, for without the lives of her little ones, her own held no purpose.

And so she attacked, her life and spirit the only weapons she had to wield against me whom she plainly perceived as a mortal threat. Size did not matter to her in the least, nor did fear, and the only thing that counted at all was the weight and scale of her own courage compared to mine.

On the other hand, my fears were firm and well founded and entirely different from hers, based not on any imminent threat or physical damage she might deliver to me personally, but on whether her courage might fail and cause her to fly and abandon her brood.

I need not have worried, and now I’m ashamed that I ever doubted her. For she wasn’t about to abandon them. Not here. Not now.

Not ever.

On she came, step by calculated step, weaving in and out of the edges of the clearing, the fierceness and bravado building in her face and carriage as she advanced, proclaiming to me and all the world that she would rather perish than betray her family—and I sensed she was resigned to doing just that.

Still fearful that she might fly, all I could do was cower there on the ground before her, fully justified in her claim against me, hissing and strutting as though she were the most savage beast in the great north woods. Her courage and confidence appeared to grow with each step, her hope of survival for herself and her chicks building in her heart with each last breath she breathed, until finally she clambered up onto a rock less than ten feet in front of me.

Lying there on my chest and stomach and watching her through my viewfinder, I could sense her subtle shift from fear to rage as she vehemently swore at me, expressing her disdain and utter indignity that I would dare presume to trespass in her woods and threaten her family. Her chest was fully inflated, her rich ebony ruff was spread wide on either side of her pulsing, russet-hued neck, and her tail was fanned full width. Her clinched, clawed feet paced rapidly up and down and more or less in place on the lichen-covered stone, her face was contorted with rage and derision, and she seemed poised for a full frontal attack at any moment as she continued her verbal assault. And once convinced that she had at last prevailed, she stepped scornfully from her granite perch and vanished into the woods.

For a moment I could hear her as she strutted away, and I listened intently for the thunderous rumble of wings. But there were no wings, no rustle of leaves nor breath of wind. Only silence, until suddenly she reappeared up on the rise where I had first seen her, body erect, head held high, her proud and probing eyes scanning side-to-side as she summoned her wayward brood.

Her voice was faint but certain as she called their names, and one-by-one, eleven pale balls of fluff scurried to her.

I know.

I counted them.

And I am quite certain that she was counting them as well, for only when the last one was safely gathered to her did she vanish with them into the darkened woods without so much as one final glance in my direction.

For I no longer mattered.

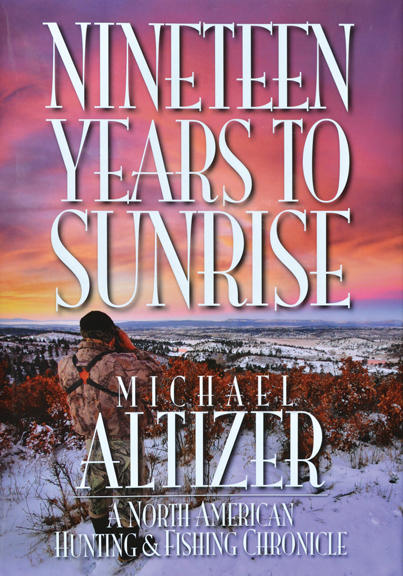

Enjoy this and many other stories from Michael Altizer’s Nineteen Years to Sunrise. Plus check out the entire collection of outdoors books at sportingclassicsstore.com.