It was to him a very simple thing and the wonder was that the others, the older ones, were so stupid and confused. It was only a matter of going back a few years to when he was ten and her age, and thinking as he had thought then.

The old urges and desires and faiths came back, and along with them the memory of the path, half-forgotten now, that followed down the tiny stream through the woods and came at the end of the cave. It was there, he decided firmly, that the lost girl had gone.

He stood a little distance from the group of men, watching the captain, noting his taut face and nervous hands.

He had always thought of the captain and of the captain’s daughter as beings apart – as, somehow, Olympian people – with whom he and his kind had little in common. He had felt that way for years, ever since the time his uncle had left him the 50 dollars and he had gone, nervous and hesitating, to his father and said that he meant to spend it for one of the captain’s fine springer spaniels.

He could remember still his father’s dark, bloodshot eyes looking at him with infinite weariness, and he could still hear his father’s voice saying, “So you’re getting big ideas. Well, you’ll get over them before you’re much older. Them fancy dogs is for people like the captain. Not for any of our kind. Keep that in mind, if you got one. We ain’t like the captain – we only work a piece of his land.”

The money had been spent for clothes for the family and a much-needed new stove, and the little that was left had gone into the meager budget.

So it was a strange thing to see the captain now as a worried and indecisive man, a man like other men, gesturing and shaking his head and saying over and over, “We’ve got to find her before another night comes. You sure you asked at every house along the Toll Road, Tom? I’m not satisfied with the way we combed that hill country, Jim.” He looked at them with bright agonized eyes.

Ben Frazier went down to the road then, tightening the loose knot in the rope that served him for a belt. The captain sure set a mighty store by his daughter, he thought.

He pulled the old straw hat down against the sun and walked faster. Soon he turned off on the little abandoned logging road and, a hundred yards along, left that to fight his way through brush to the forgotten trail. He saw a strip of bark torn from a log, broken branches and a shoe print in the mud next to a small spring. He smiled. He knew where the lost girl was.

He found her at the old cave, as he had expected, and she was too tired and frightened to answer when he told her shortly that they were going home. They walked side by side up to the house.

He was about to leave her when he heard a call and saw the captain coming toward them.

He shifted uncomfortably from one foot to the other while the captain bent and held his daughter close. Then the captain, clinging to the girl’s small limp hand, rose and turned to him, the tightness gone from his face now, the lines fewer and not so deep. He said, ”I’ve seen you around – you’re Frazier’s son, aren’t you?”

“Yes, sir.”

The captain ran a hand through his hair. “What do you want, boy? You’ve got something coming.”

He shook his head and turned away. “That’s all right.”

The captain laughed. “Maybe she would have come home by herself today. But saving me an hour or two of worry is worth plenty. Tell me what you’d like, boy.”

He drew a sharp breath. He thought of the kennel back of the house and the fine new litter. The captain was a dog man. He raised the best springers in the state. The captain owned the greatest springer that had ever lived, and this dog had sired the new litter. But dogs like that were rich men’s dogs.

He settled his feet in the roadbed. “I’d like a dog. One of your dogs. Only I know it’s too much to be asking.”

The captain looked at him for a moment, then nodded and said, “Nothing’s been sold out of the new litter. You can have your choice of it. I didn’t plan to sell for two weeks. If you want to wait, you’ll be able to make a better pick. I’m promising you I’ll sell nothing until you’ve had your pick.”

He had to think the words over in his mind before they had any meaning. Then he had to look into the captain’s face again to make sure he wasn’t having the cruelest kind of sport that any man had ever had. And when the words came out of his throat at last, they came in a voice he had never heard before.

“If you mean it – if that’s all right, I’ll pick now.”

It was a litter of eight; he knelt and ran his hands over them lovingly. He looked at their tremendous feet and their bright, sad faces; he watched the eternal movement of their sterns and thought that surely he was dreaming. After a long time he stood up and saw that the captain, whom he had forgotten, was still leaning against the fence.

The captain smiled at him. “If you want my advice, I’d take that big fellow. I never saw a better chest, and if he turns out gun shy I’ll eat him.”

The captain’s advice was honest; Ben had watched dogs all his knowing life, and this was the likeliest specimen. Most men would take him. Only there was another of the males that he had been watching. A little small, maybe, and he certainly didn’t stand out in a litter as fine as this. He couldn’t have told why he preferred him to the rest. It “vas something felt, something beyond and alien to words.

“I’d like him,” he said. The captain looked puzzled. “He seems to me a little on the nervous side. But it’s your choice, not mine; and I’ve made my mistakes.”

“I’ll take him now, if it suits you.” The captain nodded and he picked the dog up. He heard the captain telling him to come back in the morning and they’d make a deal about food- he wouldn’t have a dog fed wrong, and feeding right was an expensive business for a man who didn’t own a kennel.

Ben said, “Thank you, sir,” and started home. A little wind had come up and he put the dog gently inside his shirt against his skin, and very soon its frightened trembling stopped.

Ben said, “Thank you, sir,” and started home. A little wind had come up and he put the dog gently inside his shirt against his skin, and very soon its frightened trembling stopped.

He did not go directly home. He knew with grim certainty what would be said when he arrived there carrying the dog. He went into a field where the clover was deep and soft as an animal’s pelt and put the dog down. The dog looked up at him, pricking his ears, his muzzle quivering and eager. Even in his great-footed awkwardness was a grace, a fineness of movement that was surer proof of his breeding than the writing on his pedigree. The dog came to him when he called, and he stroked him for a few moments, then stood up, suddenly austere. You could harm the finest dog ever born with an excess of attention.

He went home then, and when he met his father he spoke first. “This is my dog,” he said softly. “The captain’s girl got lost. I found her. He gave me the dog.”

His father looked at the dog with fathomless eyes. “So the captain did. I guess you’re about one of the captain’s buddies. No doubt you’ll be going into the city soon to buy yourself some of those swell clothes like he wears. A blooded dog like that expects a lot of a man, all right. Why, he wouldn’t lower hisself to bark at anyone like me.”

Ben said nothing. The dog lay at his feet on his back, the four immense paws waving. And while he looked at him, he changed from a puppy into a grown dog, all grace and power and sureness and intelligence, the finest sight any man’s eyes had ever seen. It was as if the dog’s whole great career had been graphed out, right down to his final victories in the great national trials that rich men spent thousands trying to win and failed a hundred times for each time they succeeded. He started to turn away.

His father said slowly, “You take that dog back.”

”I’m not taking him back.” He said the words without passion, the way you say a fact beyond denial.

When his father turned suddenly on his heel and went into the house, he knew he had won the first round. He took the dog to the barn, where there was old wire and boards, and started the job of building an enclosure and a doghouse.

It seemed to him that each day really began at evening, when he was done with his work and could have some time with the spaniel. He was prepared for his father giving him more and more jobs to do. He made no complaint. He worked harder than ever in his life and knew no weariness. The most onerous work was easy when you knew that once it was finished you could do what was closest to your heart. He and his father talked little. His mother had nothing to say concerning the dog; it was obvious that she thought of him as only a creature that ate food and barked at nothing and tried to come into the house where he wasn’t wanted.

He thought a great deal about a name for the dog. You couldn’t call one

of the captain’s spaniels Bill or Pete or Boy. He had to have a dignified name, with style. It came to him in the middle of one night. The nearest town was Derrydale, and the captain had given the dog. Derrydale Captain. Derry for short.

He worked slowly, patiently, first teaching the dog obedience. He taught Derry to come to him, to walk at heel and to sit at his feet without jumping on him. After each lesson he lay on the ground and let the dog run about as he pleased, watching him all the time.

Often he talked to Derry, telling him in short, definite words what his life was to be. He held him by the scruff of his neck, and tried to make him understand all that was wanted of him, all that he must do. Once his father came up to him at such a time and announced his arrival by a laugh.

“That must be a wonderful dog you got. Talks English just like a human, I see. Or maybe you’re a little cracked in the head.”

He stood up and faced his father, feeling an impotence, a harsh knowledge of his inability to say in words the thoughts that boiled within him. When he turned away without answering, his father laughed again, a long laugh. He wondered, his blood pulsing hotly, that any man could be so unfeeling. Then his father walked away almost jauntily, as if he had achieved a victory. He had no heart for training that evening and put Derry into his kennel. He awoke in the middle of the night feeling deep shame that he had let himself be so disturbed by nothing. His father was only a man who did not see as he did.

Twice each week he went to the big house to get food for Derry. He didn’t feel that this was charity; he and the captain knew such a dog must have certain foods and that was all there was to it. Sometimes one of the hands would get the food for him. Other times the captain would be there and they would talk.

“How’s he coming along? Taught him anything yet?”

“He’s coming along pretty good. ”

“Bring him next time you come, I’d like to see him.”

“Yes, sir,” he always said. But he didn’t bring the dog next time. He didn’t intend to. He didn’t want the captain or anyone else to see Derry until he was right.

One night Derry looked poorly. His eyes were watery, the underlids half closed. He felt a surge of fear like a knife between his ribs and he stayed up all night keeping the dog warm, watching, feeding him warm milk. In the morning Derry was definitely improved. It wasn’t distemper, after all – just a slight cold.

His father was waiting for him. “Did you go to bed last night?”

“No.”

“You stayed up with that dog. I suppose he coughed or something. Well, I’m telling you this – I’m not letting any dog interfere with the work around here. I’ve let you keep him so long as you held your end up. This is too much. No man’s fit to work without sleeping. And -”

He said, “You’ll have a better idea when the day’s over what I can do.” He drove himself to the most productive day’s work of his life. When his eyes were burning and muscles fairly screamed for the lack of sleep, he increased his exertions. His father said nothing.

The next morning Derry was in perfect fettle, jumping at the wire and crying to get out for a run. He allowed himself to pet him a little longer than usual that morning.

Derry took to retrieving quickly, but he had a naturally hard mouth and many hours of work with a feather-covered ball, in which needles were cunningly placed, were needed to break him. When Derry was six months old it was late summer and time for him to know the sight and sound and scent of pheasant.

Ben took him into the remote corn patch one Sunday morning. He fastened a long line to the round collar of saddle leather that he had bought with money long saved for another purpose. Then they started slowly through the corn. Ben was speaking softly to Derry now and then to restrain his bouncing eagerness. A young rooster flushed five feet ahead and rose cackling into the air. Derry broke and Ben called to him, not raising his voice. The dog rushed on, barking now, oblivious to everything but the bird soaring towards the shelter of the woods. Ben held the line firm and Derry tumbled over backward, gave a small cry, more of surprise than pain, and came trembling to his feet.

Ben went on as if nothing had happened. The same thing happened half a dozen times. After that Derry stopped dead in his tracks when his name was spoken, even when three birds were flushed at once, not ten feet from him.

They went home at noon and Ben himself was trembling with excitement. His father was sitting smoking in a rickety chair in the sunshine, and Ben was so eager to talk to someone that he blurted out the news as soon as he reached him.

“You should have seen him with the check line – he got into it in no time. I knew it took weeks to break some of the captain’s good dogs. I tell you this dog’s got something no other dog I ever saw has.”

His father blew a spiral of gray smoke into the clear air. “Wonderful,” he said. “Maybe he can smell out a gold mine. I hate to remind you of it, but we’re poor people and we’re supposed to work at things that make a little money.”

“A good bird dog’s worth money,” he said. “Big money.”

“That may be,” his father said. “I don’t doubt it. Now, if you think your high-toned dog’s worth something…”

Ben spoke over his shoulder, “There’s not enough money in the world to buy this dog.”

His father made no answer. Ben walked quickly away. He had been burdened suddenly with a dark fear that clung to him stubbornly, try as he might to shake it off.

He felt his heart beating hard and too fast the day he first went into the field with his old hammer gun and a pocketful of shells he had loaded himself with light charges. He let Derry go a good way off, then fired. Derry started, looked about and cowered, belly to the ground. Ben walked toward him, firing twice as he came; the dog broke and ran out of sight into the woods. He called him, but Derry was a long time coming back.

When the dog returned to him, shaking as if with a fever, he stroked him lightly until the fear had passed. Then they returned home.

For five days each evening at feeding time he put the tin plate of food down and waited until Derry came for it. Then he fired into the air. The dog ran into his kennel and Ben took away the plate. On the fifth day the dog’s flanks, to Ben’s agonized eyes, were thin as paper. He wanted to give in, to let Derry eat in peace and afterward to sit by him and let him lick his hands and look at him worshipfully with his great spaniel eyes. But he steeled himself and waited.

He worked until darkness made work impossible, the week before the opening day of the pheasant season. He walked the five miles into town and back on Sunday to buy his license, then stayed up late that night to load shells and clean the old shotgun. The evening before, he told his father he wanted the day off.

“I been working extra,” he explained quietly. “I’ve done a good day’s work ahead and more.”

“And if I said no -”

“I’d go anyway. I have to go. This is my first chance to see what he can do. Only – I’d rather have your say-so.”

His father shrugged. “Do what you like. If you’re as crazy – dog crazy – as that, there’s nothing I can do to help it.”

He chose a place where no others were apt to go. He was there before dawn broke, waiting with Derry pressed against his knees. He didn’t expect many birds. It was not a real good place. If he could only bring one or two down, he’ d be satisfied. Then he’d know where Derry stood.

They worked two hours, the dog crossing and quartering the ground before a bird was raised. It was a fine shot, going away, and he made it a clear kill. He saw the cock fall and the dog go forward to it. He stood still, his hands shaking so he could hardly support the gun. Then, through misty eyes, he saw Derry coming to him, the pheasant in his jaws. He straightened and waited; the dog sat down before him and placed the bird lightly in his hand.

He drew a long breath. He’d seen the captain’s dogs work, and only one of them handled a bird in handsomer fashion. That dog was the champion who had sired Derry.

He said aloud, “You know, you, there’s no dog young as you in the world that’s in your class. And someday there won’t be any dog in the world as good as you, no matter how old and smart he is.”

He got his last bird just before it became too dark to see. Derry raised it out of a small corn patch, and Ben swung and brought it down with a side-angle shot. A moment later Derry retrieved. It was then that he felt someone watching him.

He turned, and 50 feet away saw a dark figure. The captain’s voice came floating across to him, soft syllabled and obviously excited.

“That was good,” he said. “That was fine, I enjoyed seeing that.”

“I didn’t know you were here, sir.”

“Heard shooting, and thought I’d wander down and see who it was. Truth is, I’d an idea it might be you.”

The captain approached and stooped to touch and examine Derry. “And I would have never picked this one,” he said. “I always pride myself for picking ’em young and picking ’em right too. I congratulate you.”

“I guess I was lucky.”

“Maybe. But there wasn’t any luck about the way you trained your dog. You did train him yourself?”

“Yes, sir.”

“Have any help at all?”

“No, sir. My father don’t care about dogs.” He was sorry at once for saying that; to tell a man like the captain that another man didn’t care for dogs was to brand him an outcast.

“I see. What’s his name?”

Ben felt his face redden as he told it. But the captain laughed and clapped him on the back and said that was a mighty fine compliment. He’d never had a finer one, the captain said, and he was grateful and happy for it. Then he said, and there was a serious note to his voice, ”I’ d like you to stop in at the house a minute. There’s something I want to talk to you about.”

Ben said, “Yes, sir.” As they walked along in silence he felt a sharp, quick sense of foreboding that robbed him of all the pleasure of the day. But he told himself it was ridiculous – the captain was his friend.

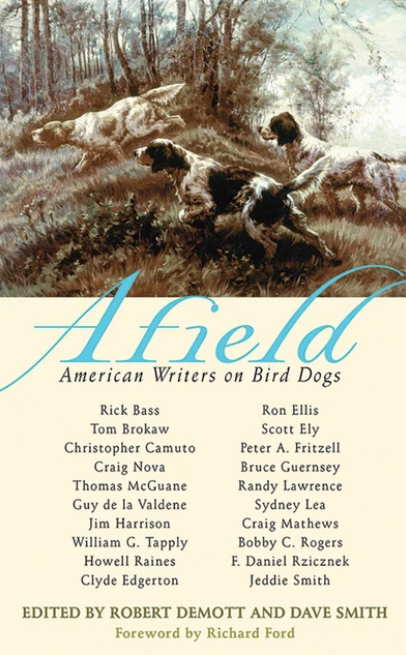

Hunters and non-hunters alike will recognize in these poignant tales the universal aspects of owning dogs: companionship, triumph, joy, forgiveness, and loss. The hunter’s outdoor spirit meets the writer’s passion for detail in these honest, fresh pieces of storytelling. Here are the days spent on the trail, shotgun in hand with Fido on point—the thrills and memories that fill the hearts of bird hunters. Here is the perfect gift for dog lovers, hunters, and bibliophiles of every makeup.

Hunters and non-hunters alike will recognize in these poignant tales the universal aspects of owning dogs: companionship, triumph, joy, forgiveness, and loss. The hunter’s outdoor spirit meets the writer’s passion for detail in these honest, fresh pieces of storytelling. Here are the days spent on the trail, shotgun in hand with Fido on point—the thrills and memories that fill the hearts of bird hunters. Here is the perfect gift for dog lovers, hunters, and bibliophiles of every makeup.

This is a delightful, handsome volume that captures the wild spirit of dogs and those who love them.This is the story of the author’s powerful connection to his family, friends and the northern outdoors. Loosely organized by the changing seasons, different sections feature essays on such topics as family fishing trips in the wilds of Maine, trophy fly fishing, turkey and deer hunting in Vermont.