Born in Rutland, Vermont, on October 18, 1867, for the first three-plus decades of his life Charles Alexander Sheldon led a fairly normal upper-class existence. He came from a well-to-do family involved in marble quarrying and spent his formative years with New England’s Green Mountains as his playground. There he developed a deep and enduring love of nature that blended outdoor activities such as hunting, fishing and canoeing with extensive reading in sporting literature. He devoured books by the likes of Izaak Walton and Frank Forester along with delving eagerly into the sporting periodicals of the late 19th century. So intelligent as to be reckoned something of a prodigy, Sheldon studied first at prestigious Phillips Academy and then Yale University.

His love of literature and years at Yale, where he was not only an excellent student but a class leader, would eventually bear important fruit. Over the course of his lifetime, Sheldon accumulated an unrivalled collection, one that bibliographer John C. Phillips described, in the dedication to A Bibliography of American Sporting Books, as a “magnificent world library on sport and travel.” Expressing similar sentiments, it was a holding that Theodore Roosevelt described as “the choicest sporting library in the country.” That splendid library of between 6,000 and 7,000 volumes was eventually left to Sheldon’s alma mater, where it remains today, forming one of the finest research holdings on the outdoors to be found anywhere. Indeed, it is perhaps rivaled only by the holdings of the Library of Congress and its somewhat selective areas of coverage, by the collection of the National Sporting Library and Museum. Sheldon’s library formed the basis for the Phillips bibliography, a landmark reference work and still a standard for modern bibliophiles. As the compiler said in dedicating the work to him, it was “in reality Charles Sheldon’s own book” and a lasting testament to “his genius as a collector and his character as a man.”

Following graduation from Yale in 1890, which came almost simultaneously with the collapse of his family’s marble quarrying business, for more than a decade Sheldon held a variety of jobs connected with railroads. The last of those, with the Chihuahua and Pacific Railroad in Mexico, provided him ample opportunities to hunt, study natural history, foster his considerable talents as a sketch artist, develop a fascination with wild sheep and other species and also become immensely wealthy. The latter development came as a result of a high-risk investment that saw him borrow $30,000 to invest in a silver and lead mine in Chihuahua. He and a mining engineer friend had discovered promising deposits on the vast lands of a Mexican acquaintance, and the resulting development of those minerals paid immense returns to all involved. Sheldon’s sudden wealth led to him retiring from the business world while only in his mid-30s. Henceforth he would hunt, explore, study natural history (especially in Mexico and the subarctic regions of North America) and become a strident, highly effective voice for conservation.

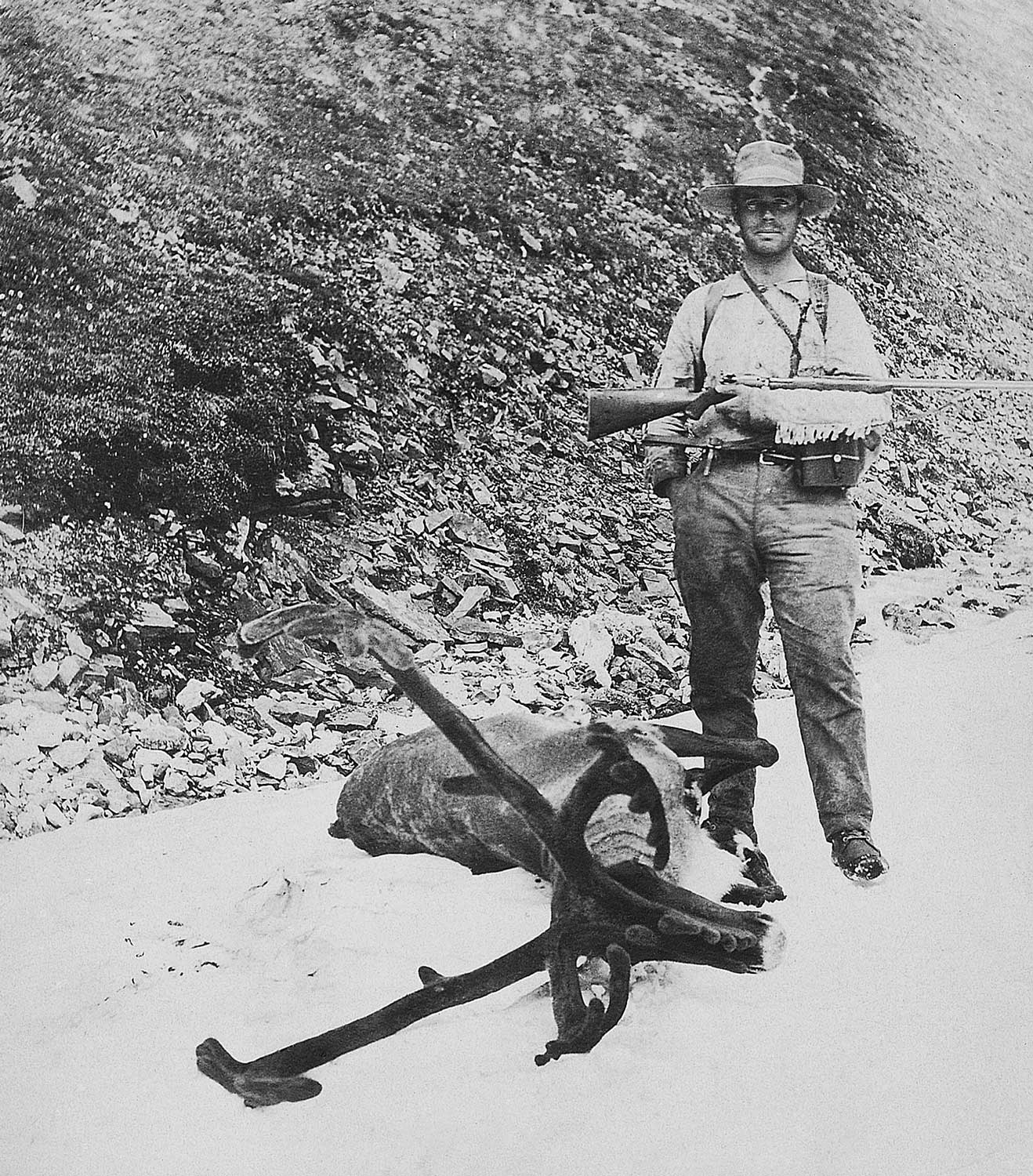

Soon after his retirement, Sheldon established contact with the United States Biological Survey and its leader, Dr. E. W. Nelson. That resulted in a series of exploratory and collecting endeavors that would define the remainder of Sheldon’s life. In the course of two expeditions in 1904, in company not only with trained scientists from the Biological Survey but first famed wildlife artist Carl Rungius and later being joined by Africa’s greatest hunter, the incomparable Fred Selous, he ventured into the headwaters of the MacMillan River and other little known parts of the upper Yukon.

Those trips, which saw Sheldon and his companions collect many trophies as well as specimens for natural history, would be the first of many to the region. Of the greatest interest to Sheldon were wild sheep, which he had previously hunted in Mexico, but his account of the initial ventures, The Wilderness of the Upper Yukon, pays appreciable attention to all aspects of his travels in the region during 1904 and 1905. The book, which has been reprinted multiple times, includes a number of illustrations by Rungius. Ex-president Roosevelt, in reviewing the book for The Outlook Magazine, described it as “one of the rare volumes which should be in the library of every man who cares for natural history and big-game hunting…described with truthfulness, with power, and with charm.” An anonymous reviewer for Literary Digest ventured “to say flatly at the outset that it is the best American production in its class since Mr. Roosevelt’s African Game Trails.”

The work, the first of three “Wilderness” volumes from Sheldon, should be read in conjunction with Selous’ Recent Hunting Trips in British North America, a portion of which describes the author’s hunts with Sheldon. Sheldon’s other works, all outgrowths of subsequent research trips in the vast subarctic region, were The Wilderness of the Northwest Pacific Coast Islands (1912) and the posthumously published The Wilderness of Denali (1930). The latter is probably Sheldon’s best-known work, thanks in large measure to the fact that it was his advocacy, more than any other voice, which led to the creation of Denali National Park. Indeed, he is often referred to, with justice, as “the father of Denali.”

After decades of being a bachelor during some of the most active of his exploring years, in 1909 Sheldon married Louisa Walker Gulliver. The couple’s honeymoon consisted of a bear hunt on Admiralty Island in Alaska and their marriage would be filled with close connection to the natural world. The Sheldons would have three daughters and a son. The latter, William G. Sheldon, would follow in his father’s footsteps as an author and student of nature, writing The Book of the American Woodcock (1967); the definitive study of timberdoodles; The Wilderness Home of the Giant Panda (1975) and Exploring for Wild Sheep in British Columbia in 1931 and 1932 (1981). He also wrote a short, unpublished memoir of his father, “Biographical Notes on Charles Sheldon” that, thanks to the helpfulness of his sister, Eleanor Lunde, I was able to read several decades ago. Eleanor also shared fond memories of summers spent at the family retreat on Lake Kedgmakoogee, deep in the Nova Scotia wilderness. Sheldon would die there, suddenly and unexpectedly, in 1928. Eleanor also offered insight into her father’s passion for preservation of the wilds as she looked longingly back to those summers and the family’s links to the natural world.

Her father’s passion for nature and wildlife translated into meaningful developments on a wide variety of fronts. One modern work that looks at Alaska describes Sheldon as “a transformational leader in the conservationist movement of the progressive era.” He was an officer and active leader in the Boone and Crockett Club and also held influential positions in the American Forestry Association and National Parks Association along with being a member of many other groups. In the fall of 1915, joining forces with other conservation leaders such as James Wickersham, the spokesperson for Alaskan territory (it did not become a state until long after Sheldon’s death); Dr. E. W. Nelson of the Biological Survey; the Camp Fire Club of America; George Bird Grinnell of the Boone and Crockett Club; John Burnham, a fellow author who wrote on Siberian hunting experiences in The Rim of Mystery and was president of the American Game Protective Association; and Belmore Browne, author of The Conquest of Mount McKinley (1913), Sheldon launched a concerted push for legislation to create Denali National Park. The effort succeeded, although to Sheldon’s chagrin it was initially known as Mount McKinley National Park. It was not until long after his death that the name used by indigenous peoples, Denali, came into official usage first for a designated wilderness area within the vast region and then later for the mountain it embraces as well as the entire park.

Along with his own timeless books and the massive library he accumulated, Denali remains Sheldon’s greatest gift to posterity. He was, in the words of George Bird Grinnell, “our most famous big-game hunter.” More than that, as C. Hart Merriam points out in his Introduction to The Wilderness of Denali, Sheldon was a man of interests “so broad that little escaped his mind [and] his contributions to the knowledge of the habits and ranges of American mammals, his continued efforts to secure adequate series of specimens for our great museums and his struggle for the reasonable conservation of wild life are among the lasting monuments to his industry and understanding.”

To read the pages of Sheldon’s “Wilderness” volumes and thus join him alongside the evening campfire with Carl Rungius and Fred Selous through his own words or those of Selous or ponder with wonder his career and achievements, is to be transported to a place of magic. He was a visionary sportsman and we are blessed to enjoy the fruits of his vision through the printed word and the delights of the world of Denali.

Jim Casada is this magazine’s longtime books columnist and editor-at-large. To learn more about his numerous books or to sign up for his free monthly e-newsletter, visit his website at jimcasadaoutdoors.com.