From this moment forward, their association will finally go down as one of the greatest in the annals of outdoor writing.

Our paths converged in a field called the Lower Forty. Corey Ford owned it, I own it — in this very real, very rural, picture-postcard New England town that he baptized and I adopted with the fictitious name of Hardscrabble. We came here, he and I, 50 years apart when we were 18 — a similarity that was one of too many to be coincidence. It haunts me.

He haunts me.

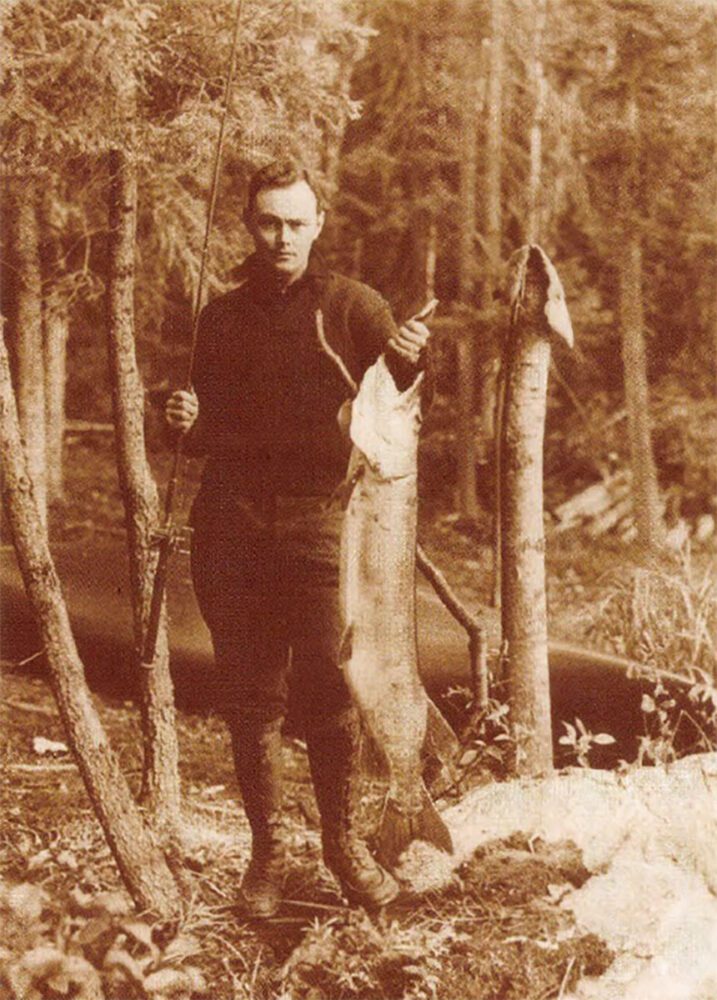

Corey caught this big muskie on a 1929 trip in Canada.

Corey Ford was the stuff F. Scott Fitzgerald made heroes of a shining child who grew up in the heyday of the Roaring Twenties to become the adored golden boy of New York literary society. He was the dark, strikingly handsome junior member of the celebrated Algonquin RoundTable who sat between Will Rogers and Harpo Marx. He christened The New Yorker’s cartoon-mascot ‘Eustace Tilley’ for Harold Ross. He knew where to push the secret button that would send the bootleg bar at the ’21’ Club crashing into the sewer in case of a Prohibition raid. He had women in chinchillas at the Stork Club, Scotch at the Player’s, and an invitation to every play Off Broadway, on Broadway and, in between, society soirees and black-tie dinners. And, when Hollywood and two-thousand Depression dollars a week as a contract screenwriter lured him to the other coast, Corey packed his bags, caught the next train, and never looked back.

In Hollywood, he was a woman’s man who wore a different starlet on his arm each night of the week. He was a man’s man whose nightly nightcap at Chasen’s was a holy ritual for him and his best friend, W. C. Fields; and when their drinking buddies Humphrey Bogart and Spencer Tracy loaded Dave Chasen’s office safe into the trunk of a taxi, Corey lent them a helping hand.

He was good to his friends that way. He gave Scott Fitzgerald a shoulder when crazy Zelda and the booze and depression kept the words from coming. He’d slip a few bucks to Robert Benchley when the liquor-moistened humorist’s lips and luck went dry, and wiped Dorothy Parker’s tears between one pathetic love affair and the next. He shook George Putnam’s hand and gave his wife, Amelia Earhart, a last kiss goodbye before she had to fly. He urged a despairing James Thurber to see through his blindness at the genius of his essays. And when Edna Ferber threatened to sue him over his Vanity Fair parody of her book, Cimarron, Corey’s apology prompted a 38-year correspondence that endured until the year before his death, when she predeceased him, He called her Smith. She called him Smith.

Corey made an enemy of Ernest Hemingway when Vanity Fair published “Corto y Derecho,” Corey’s brilliant, merciless parody of “The Snows of Kilimanjaro.” They should have been friends: Hunting, fishing, war, wine and women were common interests they each passionately pursued. But Papa stuck to his guns and his grudge right up until the day he pulled that suicidal trigger.

Burying Hemingway’s rejection along with certain dark secrets he cloistered in his heart, Corey continued to craft, perfect and lead a charmed life among charming people until December 7, 1941, when he — and the world – would change forever.

America was finally at war and damn if Corey wasn’t chafing to get into the thick of it. At 40, his age was against him, but through dogged perseverance and personal links to the chain of command in Washington, D,C., Lt. Col. Corey Ford bypassed the ranks and was commissioned to chronicle the battles of the U,S, Army Air Corps. Now he was a renegade with a heart, traveling from the Aleutians to Normandy for Look, Saturday Evening Post and Colliers. By day, in the line of fire and path of shrapnel, he wrote riveting firsthand accounts of the airmen’s battles. By night, under a blackout sky lit by stars and bomb bursts, he wrote to too many mothers and fathers. He held their fallen sons close and closed their eyes after the last breath. And in his letters, Corey recounted the brave acts and conveyed the dying words, which always were: “Tell my mother I love her.”

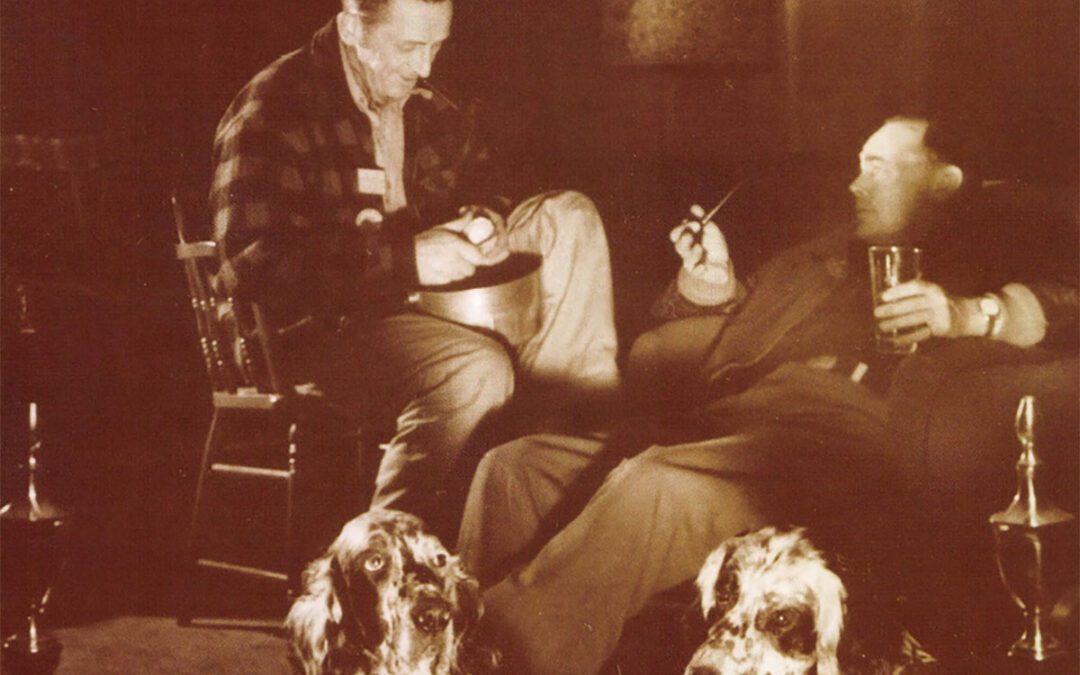

Corey in New Hampshire in the ’50s with Tober, Cider and Dr. James Hall. The “Doc Hall” character in the Lower Forty was named after Jim.

When it was all over and he saw how the world had changed, Corey realized that he too had changed. Hollywood no longer held any allure. Tinsel Town had become tarnished. Fields was dead, Fitzgerald was dead, and the starlets were married matrons. So he sent a couple of telegrams -one to his boss, Gone With the Wind producer David O. Selznick, and one to his mistress, telling them he wouldn’t be back. There was only one place to go. He went home, to Hardscrabble, where here invented himself. Here, at the age of 45, the person Corey Ford really wanted to be was born.

The timing could not have been better. The front door to a bright and promising future for America had swung wide open and the back door to the past was shut against the memory of the extravagant 20s, the depressed 30s and the war-torn40s.

Corey approached the 50s — and his 50s — reincarnated as a balding, portly, pipe-smoking country gentleman. He was comfortable in his expensive, slightly worn tweed jacket and military surplus Jeep, and for the first time in his life, he was comfortable with himself. Corey was passionate about his Parker 16-gauge, autumn, dark trout pools, secret grouse coverts and his English setters. He no longer wrote about the things he observed; now he wrote about the things he loved.

The seed had been planted one wintry February afternoon in 1935 when Ray P. Holland, chief editor of Field & Stream, scrawled a note from his downtown Manhattan office and stuck it in an envelope along with a letter he’d just received.

“I have always had the feeling,” he wrote to Corey, “that when a fellow is complimented without any intention of the compliment ever reaching him, it is one hundred percent net and sincere. I hope this stirs you into action as far as Field & Stream is concerned.”

The letter said, “Get Corey Ford to write a story for Field & Stream about the fishing trip he took last summer through Canada. He happens to be a favorite writer of mine and I’d just like to see what he’d say about the trip. The gentleman can write fishing yarns. And I know it’s none of my business to be telling Field & Stream what to do but I would get a wallop out of such a story and maybe there are a lot of other readers who would, too.”

Ford obliged. Readers related to his witty, self-deprecating sort of humor in articles such as: ” ‘Helpful Hints for Sportsmen,’ by Field & Stream’s expert who has spent 20 years in the woods, most of them trying to find his way out again” – and demanded more. He wrote about fishing for muskellunge and bear hunting in Canada, quail hunting in the Deep South, and pa’tridge hunting in his own backyard here in Hardscrabble. He wrote about his dogs. And he wrote about his friends, a casual brotherhood of college-educated, consummate sportsmen who shared a dry, devilish wit and a dedication to single malt Scotch.

There was the formidable “Judge Parker” Merrow: municipal magistrate, publisher of The Carroll County Independent, and devout family and Labrador retriever man. There was Dartmouth College’s revered secretary, “Cousin Sid” Hayward, self-proclaimed kin on the grounds that Harvard’s setter was a littermate of Corey’s beloved dog, Tober.

The others made up the most illustrious masthead in Field & Stream history: Holland and his son, fishing editor Dan Holland; humorist Ed Zern and field editors Ted Trueblood and Frank Dufresne. They argued incessantly about whose bird dog was the birdiest, overstated the weight of their game bags and exaggerated the size of the fish they caught. Their antics would become the inspiration behind one of the most popular and beloved columns in the history of outdoor publications.

In 1952 Corey agreed to write a monthly column for Field &Stream. He called it the “Minutes of the Lower Forty.”

It immediately took on a life of its own. The hilarious escapades of the eccentric, irresponsible, irrepressible group of outdoorsmen who called themselves the Lower Forty Shooting, Angling and Inside Straight Club captivated the hearts of people who hunted and didn’t, fished and didn’t, laughed and cried and cherished the unadulterated honesty and warm humor of Corey’s barely veiled, true-to-life stories. Readers flocked to become charter members, and over the ensuing years, Lower Forty clubs sprang up all over the world, from Maine to Vietnam, where Corey’s columns gave laughter and a touch of home to American soldiers. People were certain they were kin to the scalawags of the Lower Forty and promptly tied their heartstrings to Hardscrabble.

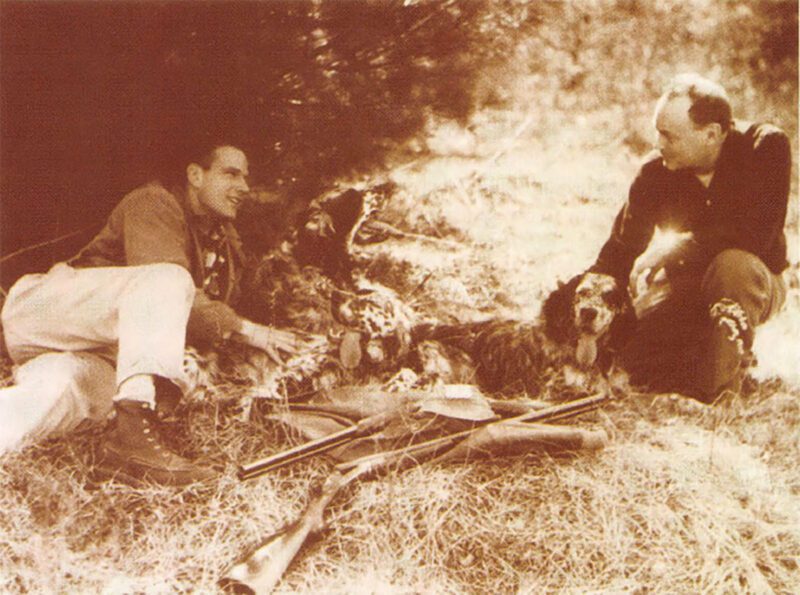

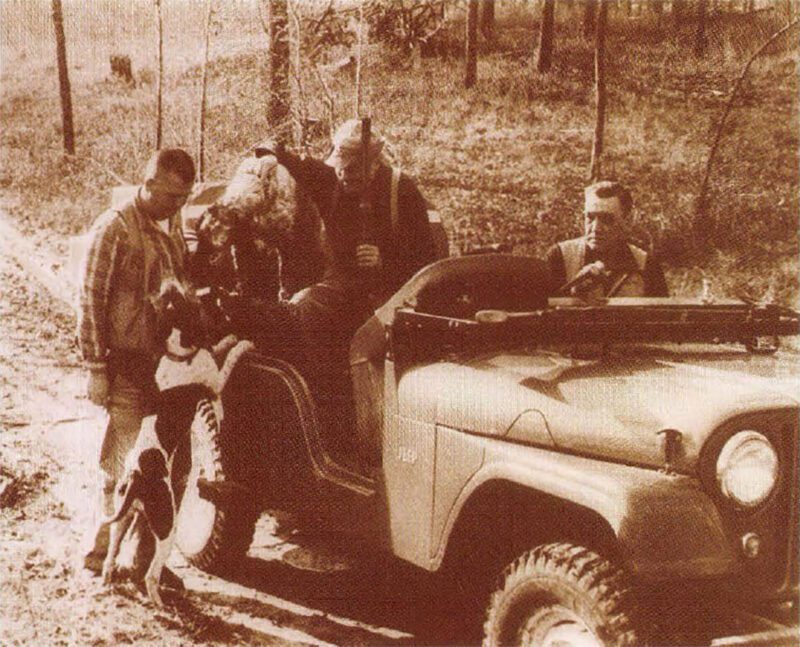

Corey and friends on the road to the place he called “Tinkhamtown. ” Below, with Alastair McBain (right), a hunting, fishing and writing partner during the ’30s and ’40s.

The stories that inspired the Lower Forty columns were based on small town life and true incidents in and around Hardscrabble as conveyed to Corey by Judge Parker Merrow. Over their 35 years of correspondence, Parker kept Corey in the loop during his frequent, lengthy absences from Stoneybroke with newsy, often hilarious letters. Addressed “Dere frend” and Signed “Yeah,” or “Up and at ’em and God Damn ’em,” Parker’s letters recounted his own court trials(often wearing waders under his robe), the comings and goings of his family and local life, and the antics of their mutual hunting and fishing cronies. Parker and Corey confabulated on the shenanigans and exploits of the colorful members of the Lower Forty Club. Parker would outline the plot, Corey would write the column, Parker made comments, and Corey would brush it up and send it to Field & Stream. This was Corey’s show and Parker wanted no credit or compensation unless it was paid out in flies and shot shells.

One particular letter to Corey from Parker, dated September 16, 1956, outlined the plot for a Lower Forty story which Corey would call “A Morning in April.” Eight years later, the same letter inspired “The Road to Tinkhamtown.”In his letter, Parker wrote: “The final message comes from the character as they go to leave his room when he tells them in essence that at life’s end you do not regret the days you spent hunting and fishing, but you do regret the days you did not spend, when you might have spent them, if you had not wasted time on trivialities — after all, the only memories a guy has left when there are just the four walls and the bed are the golden mornings and the red sunsets.”

Corey started “Tinkhamtown” on April 18, 1964, when he received the news that his “Dere frend” had died. In a magnificent eulogy called “Across the Years” for Field & Stream, Corey wrote: “He died suddenly the other day. It is still hard to believe it. A tall tree stands on a mountaintop, and every day you have seen it there, and one day you look and the tree is gone, and there is an empty place in the sky. There will always be an empty place. I’ve known a few great men in my life. Parker Merrow was one.”

From this moment forward, their association will finally go down as one of the greatest in the annals of outdoor writing.

With Alastair McBain (right), a hunting, fishing and writing partner during the ’30s and ’40s.

When “The Road to Tinkhamtown” appeared two months after Corey’s death, at the age of 67, in the October 1969 issue of Field &Stream, it was lauded as the “swan song” of the man who brought tears and laughter to millions of sportsmen the world over. Corey was in Ireland when an aneurysm forced him to return home for emergency surgery at Mary Hitchcock Hospital, a stone’s throw from his palatial home on the outskirts of Dartmouth College. He was recuperating at Dick’s House, a convalescent home on campus, when he made a phone call. “Bring me Tober,” he said, referring to his English setter, a son of Cider. A half-hour later, they brought his beloved dog into his room — only to find Corey unconscious.

He was half-paralyzed by the stroke. The doctors determined there was nothing they could do, so he went home, where his housekeeper and a nurse could care for him. One morning he indicated he wanted to go to the bathroom to shave, alone. Moments later, there was a crash. Corey had suffered a second stroke. This time, he was in a coma.

The ambulance took him to Mary Hitchcock. Corey was put in a private room. An undergraduate who boarded at Corey’s followed with Tober. Corey would want Tober. The boy led the dog up the fire escape and when the coast was clear, sneaked him into Corey’s room.

Tober jumped on the bed, lay down beside Corey, and put his head gently on his master’s shoulder. Corey was still in a coma.

G’orey Ford with Cider (right) and Cider’s son, Tober. Tober would survive Corey by one year to the day.

And in that coma, Corey Ford raised his arms, put them around his beloved dog’s neck, and died.

When he got the news, the editor of Field &Stream took out the dusty, forgotten manuscript that had been buried in the bottom of his desk drawer for so long. He remembered how time and time again, Corey had begged him to publish his story. “It’s the best thing I’ve ever written,” Corey had insisted. But the editor declined, “Our readers won’t get it.”

Corey Ford wrote “The Road to Tinkhamtown” five years before his death. It was not his ‘swan song’ — that was tripe served to cover the unforgivable blunder of an inept editor. Corey Ford had been right: “Tinkhamtown” was best thing that he — or anyone else, for that matter — had written in all of outdoor literature.

I found the original manuscript 25 years later in a cardboard box. It had been edited badly. I put it back together. This is the way Corey meant for it to be. No, my friend, “The Road to Tinkhamtown” was not Corey Ford’s swan song.

It was his autobiography.

Is Tinkhamtown a real place? Sure it is. Everything is the way Corey said it was, down to the lilac trees. Majestic elms still surround the cellar-holes, vestiges of homes that were once alive with people, and the elms that were so hard hit by disease are now sprouting new saplings and branches. Tinkhamtown is alive again.

Only one time did I ever bring someone to Tinkhamtown. When we came to the bridge, he stopped. He refused to cross.

He said it was not his time.

Each of us walks our own road in Life. And when it is our time, perhaps we too will cross the bridge.

Editor’s Note: this article originally appeared in the 2001 August issue of Sporting Classics.

A Year Outside demonstrates “…his work fits more closely with the giants of yesteryear such as Robert Ruark, Corey Ford, Nash Buckingham, and Archibald Rutledge than with today’s how to’ and where to’ writers.” – Sporting Classics. Buy Now

A Year Outside demonstrates “…his work fits more closely with the giants of yesteryear such as Robert Ruark, Corey Ford, Nash Buckingham, and Archibald Rutledge than with today’s how to’ and where to’ writers.” – Sporting Classics. Buy Now