“I don’t deliberately try to make my paintings look different from other people’s, but maybe one of the reasons they do is because I don’t consciously imitate anyone artist’s approach.”

Assuming that you buy Mark Susinno’s explanation, it is conceivable to believe that he had gone to the Susquehanna River purely on a “research mission,” but then again, by employing commonsense, it is equally plausible to think the fish painter from Maryland had simply gone bonkers. With a winter’s chill advancing upon, Mark and angling partner Harry Weiland had ignored the falling snowflakes and agreed that in order to beat the crowds, they would launch their boat and go casting for small mouth bass. Of course, it wasn’t as if the broad channel brimmed with other traffic. They were alone, with the surging whitecaps all to themselves.

Assuming that you buy Mark Susinno’s explanation, it is conceivable to believe that he had gone to the Susquehanna River purely on a “research mission,” but then again, by employing commonsense, it is equally plausible to think the fish painter from Maryland had simply gone bonkers. With a winter’s chill advancing upon, Mark and angling partner Harry Weiland had ignored the falling snowflakes and agreed that in order to beat the crowds, they would launch their boat and go casting for small mouth bass. Of course, it wasn’t as if the broad channel brimmed with other traffic. They were alone, with the surging whitecaps all to themselves.

“It was late November and the wind was 20 miles-an-hour and gusting to thirty,” Mark recalls. ”I’ll never forget the sight of all that spray leaping fifteen feet in the air as the waves crashed against the rocks. You might say it was memorable.”

Each quaking slam of the bow sent an icy torrent raining down on Susinno in the rear of the craft. The water froze into a sheen on his jacket and frosted his eyelashes. It closed the guides on their rods and numbed their fingertips. The day wasn’t perfect, but any fisherman who waits for utopian conditions probably has spent more time surfing on a TV channel clicker than looking into a fish finder. The fact that conditions were not good — make that downright miserable — affirms the extent that Mark Susinno will travel to grasp the authenticity of a fishing scene.

“We were the only maniacs on the river that day, but amazingly, ” he says, flaunting a grin, “we caught a number of nice smallmouths.”

At age 37, Mark Susinno is arising force in the portrayal of fresh and saltwater gamefish. His accolades are numerous, ranging from a string of victories in thirteen fish stamp competitions to the covers of angling magazines to original works that have been juried into several museum exhibitions.

“I think out of all of them, Mark Susinno is the finest painter of underwater fishing scenes we have today,” says Bubba Wood, owner of Collector’s Covey in Dallas Fort Worth, which is marketing the print of Susinno’s design (red fish) for the ’94 Texas Saltwater Fishing Stamp. “He seems to have come out of nowhere,” Wood adds, “but everyone I’ve spoken with, I mean people who fish a lot, have good things to say about him.”

A dozen years ago, Mark went to work every morning carrying a lunch pail under one arm and a cutting torch int he other. The only blue he knew was the collar of his shirt, not the aquamarine tints on a canvas. It was the beginning of Ronald Reagan’s glorious 1980s, when the brightest educated minds left college to get rich on Wall Street. But across the East River in Brooklyn, a long way from Susinno’s upbringing in suburban Washington, D.C., he was adrift in the tedium of getting by. He first labored for a scrap-metal business, then moved on to fabricating bullet-proof doors. What any of this has to do with a promising young artist — classically trained, who graduated with high honors from renowned Pratt Institute — was a question that Susinno began asking himself.

A dozen years ago, Mark went to work every morning carrying a lunch pail under one arm and a cutting torch int he other. The only blue he knew was the collar of his shirt, not the aquamarine tints on a canvas. It was the beginning of Ronald Reagan’s glorious 1980s, when the brightest educated minds left college to get rich on Wall Street. But across the East River in Brooklyn, a long way from Susinno’s upbringing in suburban Washington, D.C., he was adrift in the tedium of getting by. He first labored for a scrap-metal business, then moved on to fabricating bullet-proof doors. What any of this has to do with a promising young artist — classically trained, who graduated with high honors from renowned Pratt Institute — was a question that Susinno began asking himself.

“When I got out of Pratt I was sick of school and sick of art,” he admits. “I actually wanted to work in a blue-collar job. But after six years of labor-type work, I came to the realization that I didn’t want to do that for the rest of my life, and frankly, I was getting tired of being told what to do day after day.”

About that time his younger brother Byron did two seemingly insignificant things that ultimately would have a major impact on Mark’s life. “He took me bass fishing,” Mark recalls. “I had tried flyfishing for trout several times, and while I enjoyed going out, I didn’t have much success. I had a lot more success catching bass and my interest in fishing grew along with it.

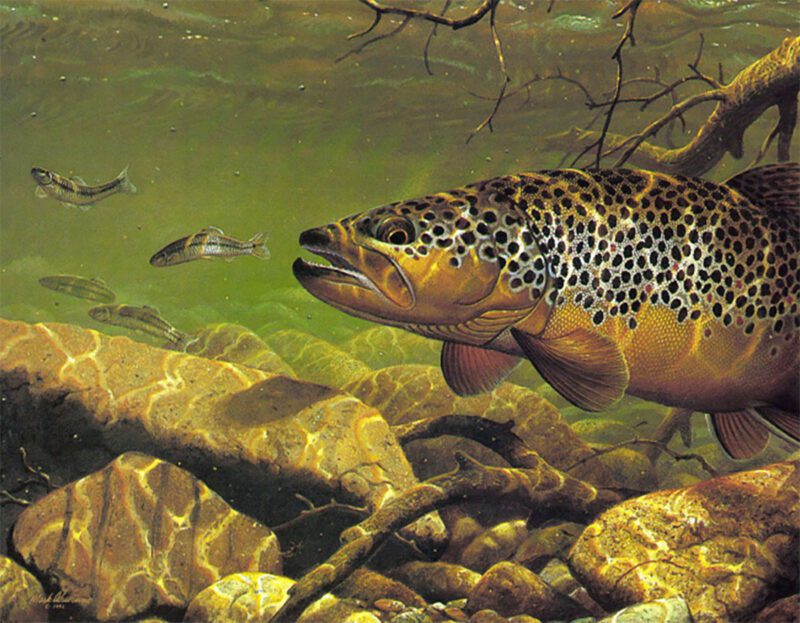

“The other thing Byron did was ask me to paint a picture of a brown trout. I had been painting all kinds of subjects in my spare time, even doing some sculpture and carvings. I had never seen a brown trout, and it was during my research for that painting that I got interested in doing fish. Then somewhere along the line I started entering trout and duck stamp contests.”

Mark’s break came in 1985 when his entry won the Maryland Trout Stamp competition. Before long, his art was appearing before thousands of anglers, on the Indiana, Delaware and Chesapeake Bay fishing stamps. Mark’s work was also noticed by the staff at Wild Wings, the same sporting print publisher that nurtured the career of wildfowl painter David Maass when the Minnesotan was a relative unknown in the early 1970s.

“I really appreciate what Wild Wings has done for me. There were hardly any fish prints seven years ago; they took a chance in publishing my work, because there was no real barometer for measuring the level of interest in fish prints.”

Susinno is thought by many to be the one who can elevate “fish art” from its lower tier status. Considering the potential market, that numbers of sport fishermen nationwide have held steady while bird hunters are declining, there is logic to the theory. And just as Maass’ limited edition prints became the darling of Ducks Unlimited banquets two decades ago, Mark’s portrayals of salmonids have become the rage of collectors at Trout Unlimited fundraisers. Dave Kolbert knows. “The only thing I can say is that I’ve never seen anyone work harder at his craft and with more focus. When you fish with Mark, he has a rod in one hand and his underwater camera in the other. As soon as you catch a fish, it gets photographed for reference.”

Kolbert met Susinno while coordinating TU’s national banquet program and has since gone to work for Wild Wings as the company’s marketing communications manager.

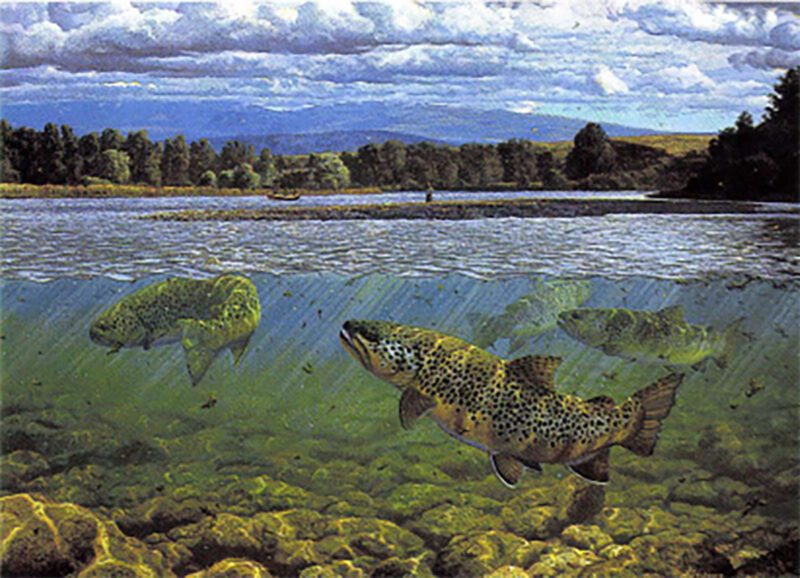

“The thing I love most about Mark’s work is that he has the ability to capture the underwater world of gamefish,” says Kolbert. “The fish are very accurate and detailed, but they are presented from an angler’s perspective as the catch is actually seen in the mind’s eye. It makes his work stand out, and fishermen find affinity in it.”

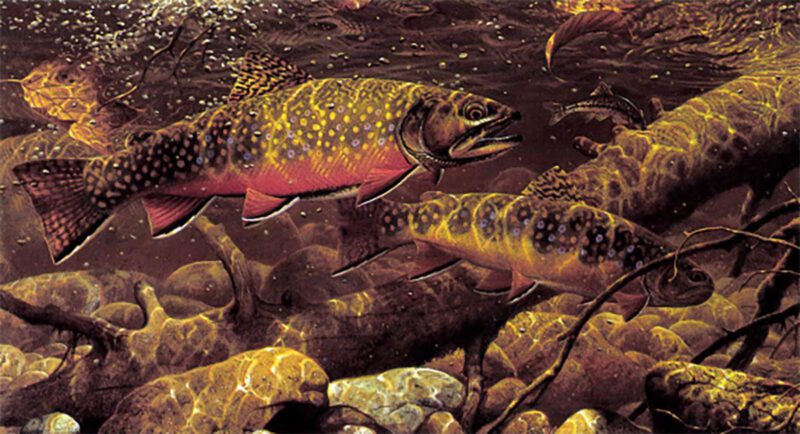

Every angler knows that once a fish is removed from the water, it quickly loses its iridescent luster. Susinno, however, holds no fidelity as to how fish appear in the murky depths. Fish, after all, are products of evolution. Their markings are camouflage, designed not to stick out. Their colors must be projected and exaggerated to make the fish appear real, he believes. Thus, in a Susinno painting, lush presentation conveys the beauty of the fish and its habitat: A northern pike, mottled in green-white-yellow, ambushes a Rapala as diamond side-markings, goes airborne above the lily pads with a deer-hair fly in its lip; a walleye, in finned regalia and golden repose, prepares to strike a deep-running crankbait.

Every angler knows that once a fish is removed from the water, it quickly loses its iridescent luster. Susinno, however, holds no fidelity as to how fish appear in the murky depths. Fish, after all, are products of evolution. Their markings are camouflage, designed not to stick out. Their colors must be projected and exaggerated to make the fish appear real, he believes. Thus, in a Susinno painting, lush presentation conveys the beauty of the fish and its habitat: A northern pike, mottled in green-white-yellow, ambushes a Rapala as diamond side-markings, goes airborne above the lily pads with a deer-hair fly in its lip; a walleye, in finned regalia and golden repose, prepares to strike a deep-running crankbait.

The trademark of Susinno’s art is the implication of action, which tells a story more engrossing than action itself. Anglers cherish this ever-moment of anticipation, the split-second that we think we know what is happening on the lake or stream bottom. To present a scene otherwise, such as a waterfowl gunning after the birds have been hit, misses the mark. Susinno’s narrative is incomplete, which draws the viewer into his composition.”

Whenever I fish, I’m trying to imagine what the lure is doing and how the fish is responding. After a while you start to think that maybe it (a strike) won’t happen again,” he says from his home in Olney, Maryland, just beyond the Beltway. “Fishing is like gambling, you replay it over and over and over in your mind – that thrill you get when the fish hits the lure. Every time you’re on the water you try to anticipate it happening in the next second, but until there’s contact, it seems like it will never happen again.”

At Pratt, Mark underwent rigorous exercises in drawing, and examined how color, value and perspective coalesce. He says that part of his inspiration as a fish painter is absorbing the body of knowledge from fellow painters who have set the standard in the genre – Stanley Meltzoff, the master of saltwater; the exquisite flyfishing portraits by Adriano Manocchia and Lee Stroncek; and the freshwater gamefish of Larry Tople, particularly those in the lake country of the Upper Midwest.

“I don’t deliberately try to make my paintings look different from other people’s, but maybe one of the reasons they do is because I don’t consciously imitate anyone artist’s approach,” Mark explains, noting that Caribbean and Atlantic Coast fish — barracuda, snook, redfish, striped bass and bluefish — are expanding his portfolio.”

Fish painters can learn from other wildlife artists, but what separates a good painter from the others is not the ability to depict the exact details of a fish or mammal, but to bring together the basic principles of art. An interesting painting to me is one that is faithful to these principles and uses them to communicate what is happening with a fish beneath the surface.”

Mark Susinno’s images are based on personal experience. A scrapbook of his “research expeditions” shows him catching 15-pound bluefish in Maine’s Kennebec River, the quarry so strong-jawed that several big blues straightened the treble hooks on his saltwater plugs. In the Florida Keys, while wading chest-deep in pursuit of boriefish hundreds of yards from shore, he felt the ripple of nurse sharks swimming a rod’s length away. He has stalked brook trout in the Catoctin mountains of northern Virginia near Camp David, where the underbrush is thick, the stream channel deep, and the banks close enough that you can leap across them. He has flyfished the upper Missouri River in Montana while a hatch of mayflies erupted from the water, then switched to a Blue Wing Olive pattern to catch several browns and rainbows.

Mark Susinno’s images are based on personal experience. A scrapbook of his “research expeditions” shows him catching 15-pound bluefish in Maine’s Kennebec River, the quarry so strong-jawed that several big blues straightened the treble hooks on his saltwater plugs. In the Florida Keys, while wading chest-deep in pursuit of boriefish hundreds of yards from shore, he felt the ripple of nurse sharks swimming a rod’s length away. He has stalked brook trout in the Catoctin mountains of northern Virginia near Camp David, where the underbrush is thick, the stream channel deep, and the banks close enough that you can leap across them. He has flyfished the upper Missouri River in Montana while a hatch of mayflies erupted from the water, then switched to a Blue Wing Olive pattern to catch several browns and rainbows.

Perhaps Mark’s favorite laboratory, the one that surprises out-of-town guests, is a body of water not far from the President’s back door at the White House. The Potomac River, once thought to be a dying waterway, today offers two exciting fisheries. The upper portion, characterized by a gradient with plenty of cobbles and snags, is ideal small mouth habitat; the lower Potomac, sedentary and influenced by the ocean tide, has been overtaken by foreign weeds. As a result, the largemouth population has exploded.

While most anglers on the Potomac use fishing boats of one form or another, Mark routinely navigates the river in the shell of a kayak. Even more unusual, perhaps, is that he may head to the historic stream at any time day or night. He recalls one particularly vivid memory of fishing the Potomac at two in the morning. “I paddled into a cloud that I assumed was a rising mist flooded by moonlight. But it was actually a hatch of midges that emitted an unearthly hum as I paddled through them. The whole thing was very strange.”

He values the abstruse — indeed, it is his trademark. A test of Susinno’s artistic strength occurred with the Oregon Trout Stamp contest in 1993. He submitted a stunning portrait of a redband rainbow trout. The release of 500 prints sold out in les then a year. “Mark does not paint a background and then drop the fish onto the top of the paper, so to speak:’ says Cal Cole, administrative director of Oregon Trout Inc., which marketed the stamp and print. “So much angling art looks like the fish was merely painted in incidentally, but with Susinno the environment is right. While water scenes tend to be cold, the colors he uses are warm. They draw the eye right in.”

Employing his canvas as a platform for education, Susinno’s compositions spill over into obvious messages of conservation. The 1989 Indiana Trout! Salmon Stamp was his first foray into depicting an underwater view of a fisherman releasing a trout. He followed that with a similar concept a year later for the Kentucky Trout Stamp. Generous in distributing his prints to fishing groups nationwide, Susinno isa board member of the Seneca Valley Chapter of Trout Unlimited.

When Lefty Kreh approached Dell Publishing about writing a book on the finer points of flyfishing, the sage angler summoned Susin no to make the illustrations. A man of Kreh’s international stature obviously had a handful of accomplished artists at his disposal, but Susinno, he said, knows the nature of catching fish — the posture, the presentations, the spirit.

When Lefty Kreh approached Dell Publishing about writing a book on the finer points of flyfishing, the sage angler summoned Susin no to make the illustrations. A man of Kreh’s international stature obviously had a handful of accomplished artists at his disposal, but Susinno, he said, knows the nature of catching fish — the posture, the presentations, the spirit.

For Lefty Kreh’s Advanced Fly Fishing Techniques, Mark completed black-and-white drawings of fly-tying, casting, retrieving and other complicated concepts that are difficult to express visually. “He conveys ideas better than any illustrator, and I have respect for his work.” says Kreh. “If you’re interested in taking stock in a good artist, buying one of his prints or paintings would be a worthwhile investment. I really believe it.”

For Mark Susinno, there will always be another research mission, another excuse to gather information for a prize-winning painting. “I’m sure it’s not a secret,” he says of melding business with pleasure. “One thing that is nice about being an artist is I can go fishing during the week.”

But will he paint fish forever? “It’s conceivable that at some point I might switch into some other subject matter. But I don’t think I’ll ever stop being a fanatical fisherman. That part of me will never change.”

Editor’s Note: This article originally appeared in the 1994 May/June issue of Sporting Classics.

Featured on these pages are more than 280 paintings dating from the early 1970s to today. You’ll join the artist on adventure-filled journeys across North America, Central America, Africa and Asia and discover a vast portfolio of wildlife, including lions, tigers, bears, white-tailed deer and more. You’ll enjoy his gripping and refreshingly honest accounts of the experiences that inspired his artwork. In his stories, Sieve shares his deep commitment to land and wildlife conservation practices and recounts his adventures observing, photographing and hunting his wild subjects. Buy Now

Featured on these pages are more than 280 paintings dating from the early 1970s to today. You’ll join the artist on adventure-filled journeys across North America, Central America, Africa and Asia and discover a vast portfolio of wildlife, including lions, tigers, bears, white-tailed deer and more. You’ll enjoy his gripping and refreshingly honest accounts of the experiences that inspired his artwork. In his stories, Sieve shares his deep commitment to land and wildlife conservation practices and recounts his adventures observing, photographing and hunting his wild subjects. Buy Now