If you were to compile an international Who’s Who in Wildlife Art, the name of Dino Paravano would undoubtedly be in it alongside Bateman and Coheleach, Shepherd and Ching.

The fact that his name is not widely known in the United States is a large part of the reason why Paravano’s address is now Tucson, Arizona, rather than Johannesburg, Republic of South Africa.

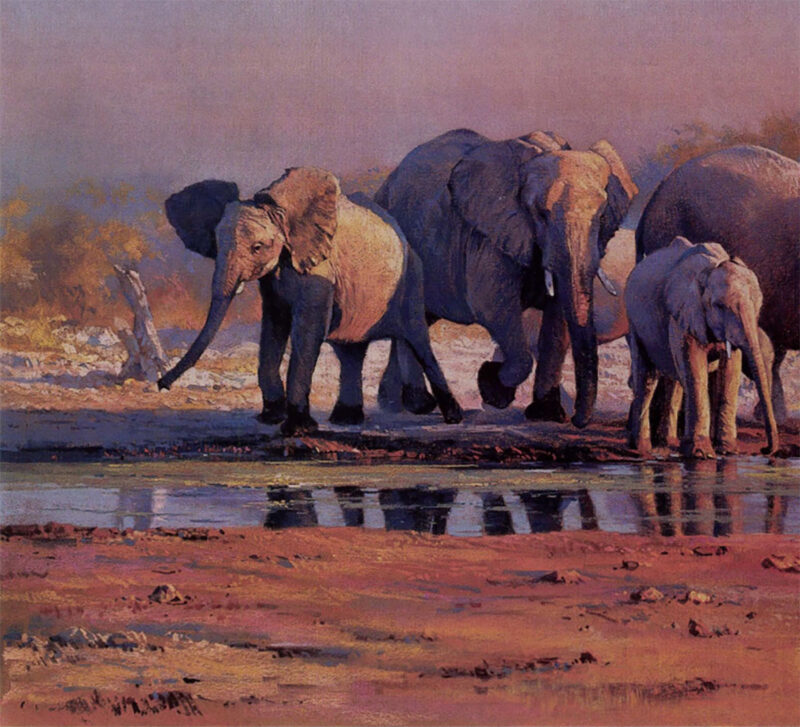

A versatile artist, Paravano used pastels for Elephant Sundowners.

“I wanted to come to the United States for a long time,” he says, “not because the market here is so much larger, but because there is so much more happening. Competitions. Exhibitions. Galleries.

“South Africa was my home for many years, and I love it and I go back every year, but the fact is, it’s very isolated, artistically.

“I wanted to be part of the big picture, and the big picture is right here.”

Dino Paravano is not, as you might imagine, a young, up-and-coming painter. He is an accomplished and established artist who has been painting professionally for almost 50 years, and relocated to the US at an age when most people are at least slowing down, if not contemplating retirement.

Born in Italy in 1935, Paravano and his family lived there through the Second World War, then fled to South Africa “on the first plane out of Rome” in 1948. They settled in Johannesburg.

Mating Time

Dino was already showing signs of his artistic propensities, to the delight and chagrin of his father, a former student at the Institute of Fine Arts in Rome.

“When I was a baby, he put art books under my pillow, hoping it would rub off,” Dino says, “And I guess it worked. All through school I loved to draw, and all I ever wanted for Christmas was more pencils and paper, more coloring books.”

However, while Dino’s father encouraged him to draw, he did not want him to take up painting until he was out of school, fearing it would distract him from his studies. A break came — literally — when he was only 12 years old. The elder Parava no broke his ankle and could not work; since the family had only recently arrived in South Africa and was financially strapped, Dino began painting seriously in an effort to make some money. His work sold and he has been painting, almost non-stop, ever since.

After a term at the Johannesburg College of Art, Parkvano worked in commercial illustration for a little over a year. But the world of graphics did not inspire him, and when his family bought a fish and chip shop, he was happy to go to work there instead, leaving his afternoons free to pursue the kind of painting he loved. For a long time he concentrated on traditional subjects and forms, such as landscapes and still-lifes, painted in oils.

When the family business was sold in 1956, Dino Paravano had progressed to the point where he could make a living painting, and he continued on, doing just that. He was only 21 years old.

Paravano’s pastels are luminous, yet true-to-life as in The Bully Elephant and Gemsbok (1996).

By 1965, Paravano had been a professional painter for almost a decade; strangely enough, however, considering his prominence today as a wildlife artist, until that time he had never considered painting animals. It had simply never crossed his mind. Then he visited Kruger National Park for the first time, and his career changed forever.

“I got my first taste of wildlife then,” he said. “Real wildlife, I mean, not zoos. I had visited the zoo, of course, but it never impressed me and I never wanted to paint anything I saw there.

“But animals in the wild were different. Those I found so exciting.”

Paravano has returned to Kruger Park every year since. He has also been painting animals ever since, and the list of his accomplishments, honors and awards has grown to several closely typed pages. He has held 14 one-man shows since 1966, in Johannesburg, New York and London, and participated in more than 200 other exhibitions all over the globe. Paravano has exhibited with the Society of Animal Artists, and received its “Best of Show” award in New York in 1984, and its “Award of Excellence” in 1990. Three years later, in 1993, he was Leigh Yawkey Woodson’s Master Artist. And those are just some of the highlights.

Although his painting career is now predominantly birds and mammals, Dino Paravano resists the label “wildlife artist.”

Leopard on Rock (1995).

“For some reason, in America, they want to label you, and once you are labeled, you’re not supposed to do anything else. I like to paint other things, and I do paint other things.”

In South Africa, Paravano made a name for himself as a painter of seascapes several years before he ever painted an animal, and he still enjoys doing that. He also paints landscapes, in watercolor, as a break from the majority of his work, which is done in oils and pastels.

“Interestingly enough, there are similarities between wildlife and seascapes,” he said. “Both are challenging. The sea will never stay still for you, and when you paint it you have to capture that quality of movement. Animals, much the same thing.”

Whatever the subject, it will be immersed in a certain quality of light that has almost become a Paravano trademark. His paintings of African big game, in particular, often impart a dramatic play of sunlight and shadow — a herd of elephants in the dappled shade of an ancient baobab, a lion family caught in the glow of an amber sunset. Paravano grew up drawing and then moved into painting in oils. He later became interested in pastels, and the joys and frustrations of that medium illustrate some of the problems facing South African artists.

“There was not much available in the way of pastels,” he says. “I ended up making many of my own pigments because I could not buy the exact color I wanted. There were a few colors available, but not many. When I wanted a particular shade, that’s what I had to have. I wanted to learn about pastels, but there were no books available there to study from.

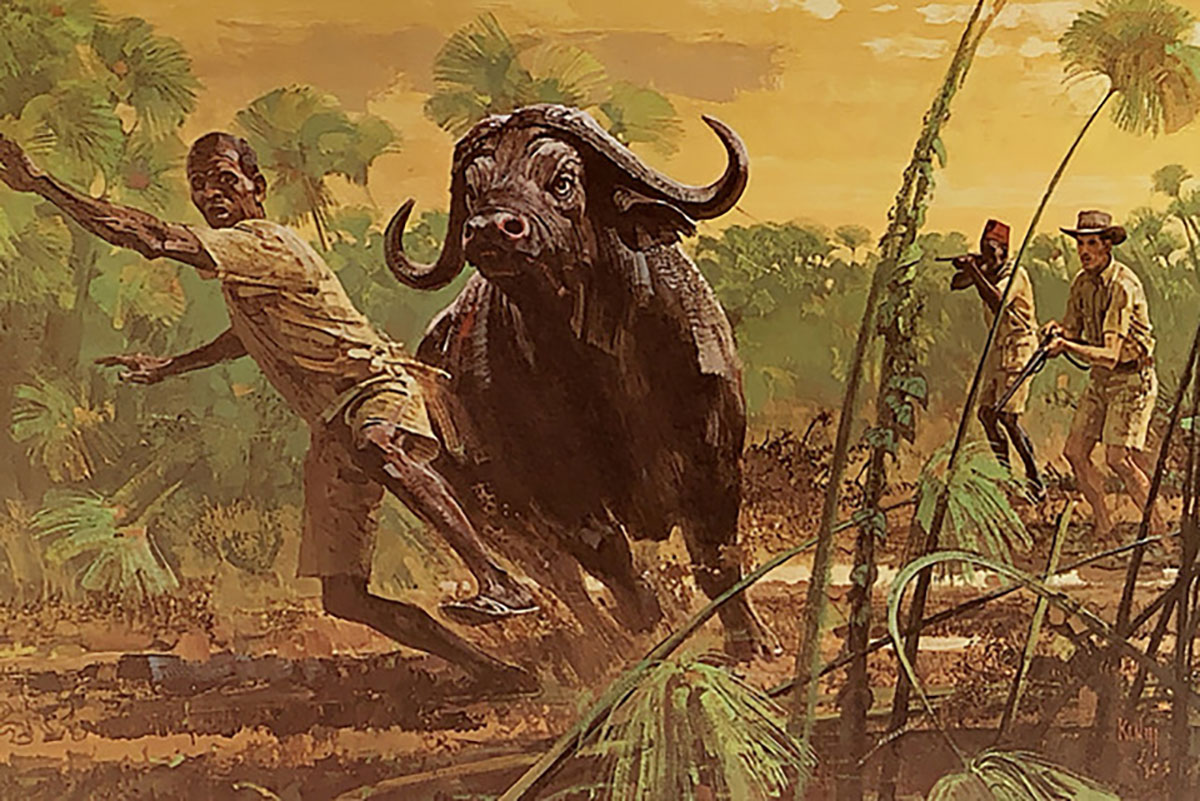

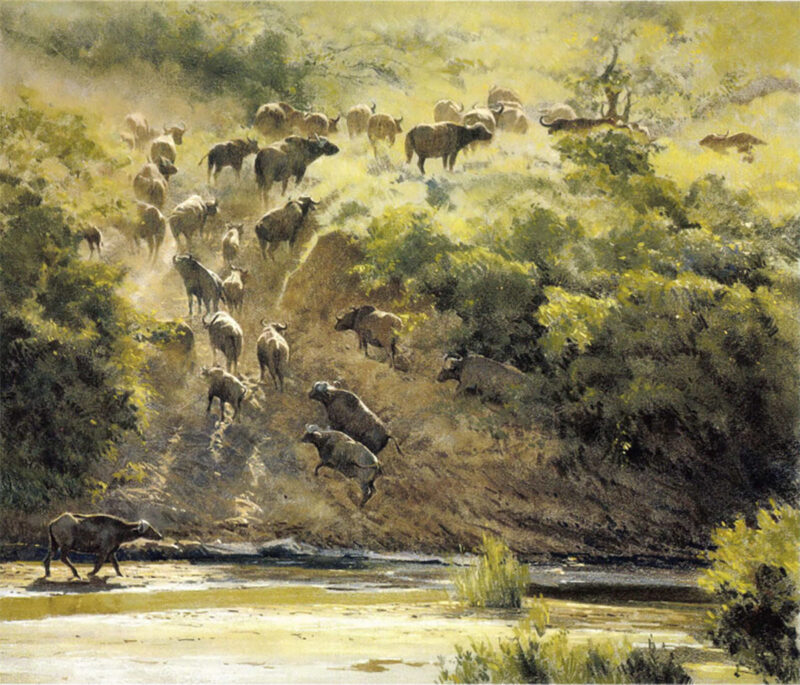

In Out of the Bank, Paravano uses strong sunlight and a swirling blanket of dust to heighten movement and drama.

“I began making my own pastels on a trial-and-error basis, and eventually I came up with a formula for blending pigments of powder with binder gum tragacanth that I got at the pharmacy. I mixed them together, then hardened the sticks in a warm oven, much like they make candy. I made 360 different colors — several thousand sticks in all.

“Looking back on that period of my life, I realize that it was difficult to succeed as an artist under those conditions.”

There were also political and personal limitations.

During South Africa’s years as an international pariah, its artists were not free to travel in many countries. For animal painters, being forbidden to visit such wildlife areas as Tanzania’s Serengeti Plain, or the Masai Mara of Kenya, was vexing, to say the least.

Its athletes were barred from the Olympic Games, a journey that Paravano might well have undertaken either as a pistol shooter (he was South African Junior Champion at one time) or a trap and skeet shooter. As well, although it was not a serious obstacle, South Africa’s bureaucratic restrictions on the movement of artworks and money in and out of the country were a nagging irritation similar to the restrictions placed on citizens of Eastern Bloc countries. By 1988, Dino Paravano was ready to get out.

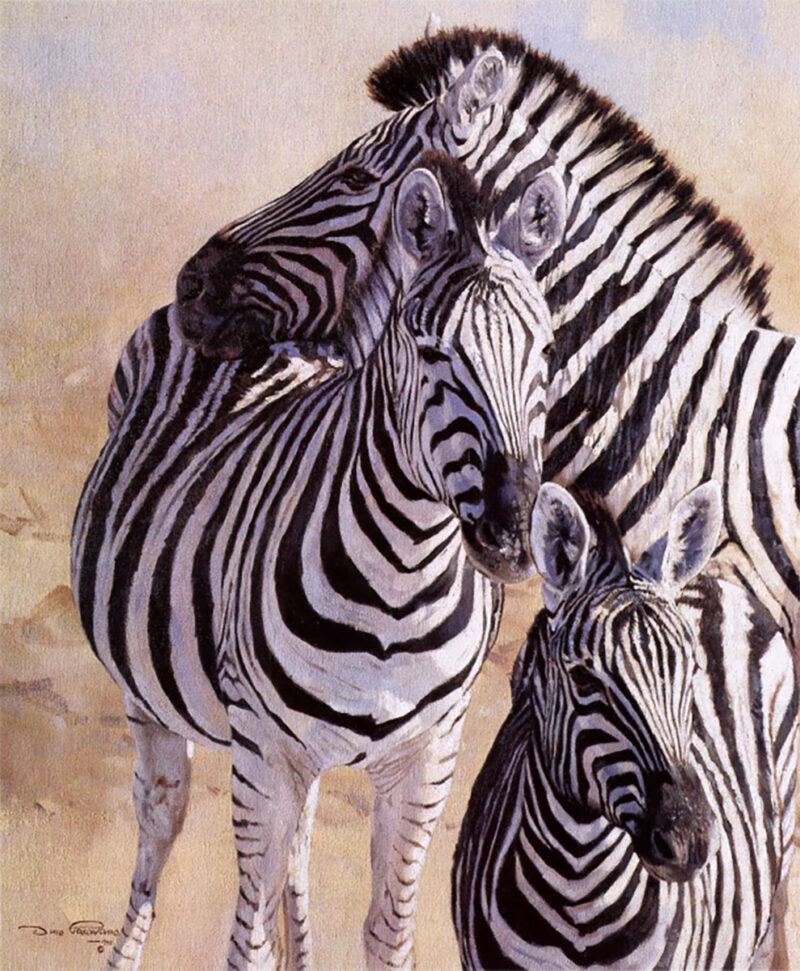

Stripes

“To put it bluntly, I’d had enough of having to ask permission to do everything and filling out forms in triplicate. I wanted to live in a free society and be part of the international scene.” Paravano and his wife, Kiki, applied for permission to immigrate to the US, and in 1992 took up residence (after a brief period in Florida) in Tucson, Arizona.

Their move to the United States was far from a shot in the dark. Paravano had been visiting the country on a regular basis since 1974, had his first one-man show herein 1976, and published his first two reproductions (in the days before limited edition prints) in 1978. When he arrived in 1991, he already had a publishing contract with Mill Pond Press. His first print, Rocky Mountain Cougars (two cubs on a snow-covered rock) was released in 1992, and has been followed by four more.

Given the fact that Paravano particularly enjoys painting lions, the choice of cougars was a natural. Other than that, he finds conditions for viewing wildlife in North America distinctly different from those of southern Africa. “I’ve traveled quite extensively in both the United States and Canada, and it surprised me how difficult it is to see animals in the wild. In Alaska I have been quite close to big bears, but for most others — frankly, you almost have to depend on seeing animals in captivity, and visit wild areas to gather material for habitat and transplant them.

“For someone used to seeing so many animals in the wild, as we can in Africa, it is rather frustrating.”

Partly for that reason, Paravano continues to concentrate on African subjects, though he also has some North American projects in mind.

“I would really like to go to Churchill (Manitoba) to watch polar bears,” he said. “That seems to be one of the few places you can go and be certain of seeing them.

“That’s the real problem: Time. Here, you might spend weeks or months in the wild before you see an animal. Even in parks, there is not the profusion of wildlife. Except for small animals, of course.”

Cougar Encounter, 1996.

If Dino Paravano took up residence in the United States to become part of the international art scene, he has more than succeeded. He now divides his time between his home in Arizona and long visits to South Africa, where his son Paolo still lives. He is represented by major galleries in New York (Holland & Holland) and London (Tryon and Swann) , as well as the Everard Read Gallery in Johannesburg. Settlers West in Tucson, Gallery Jamel in Maryland, and Trailside Americana in Carmel, California, also carry his work.

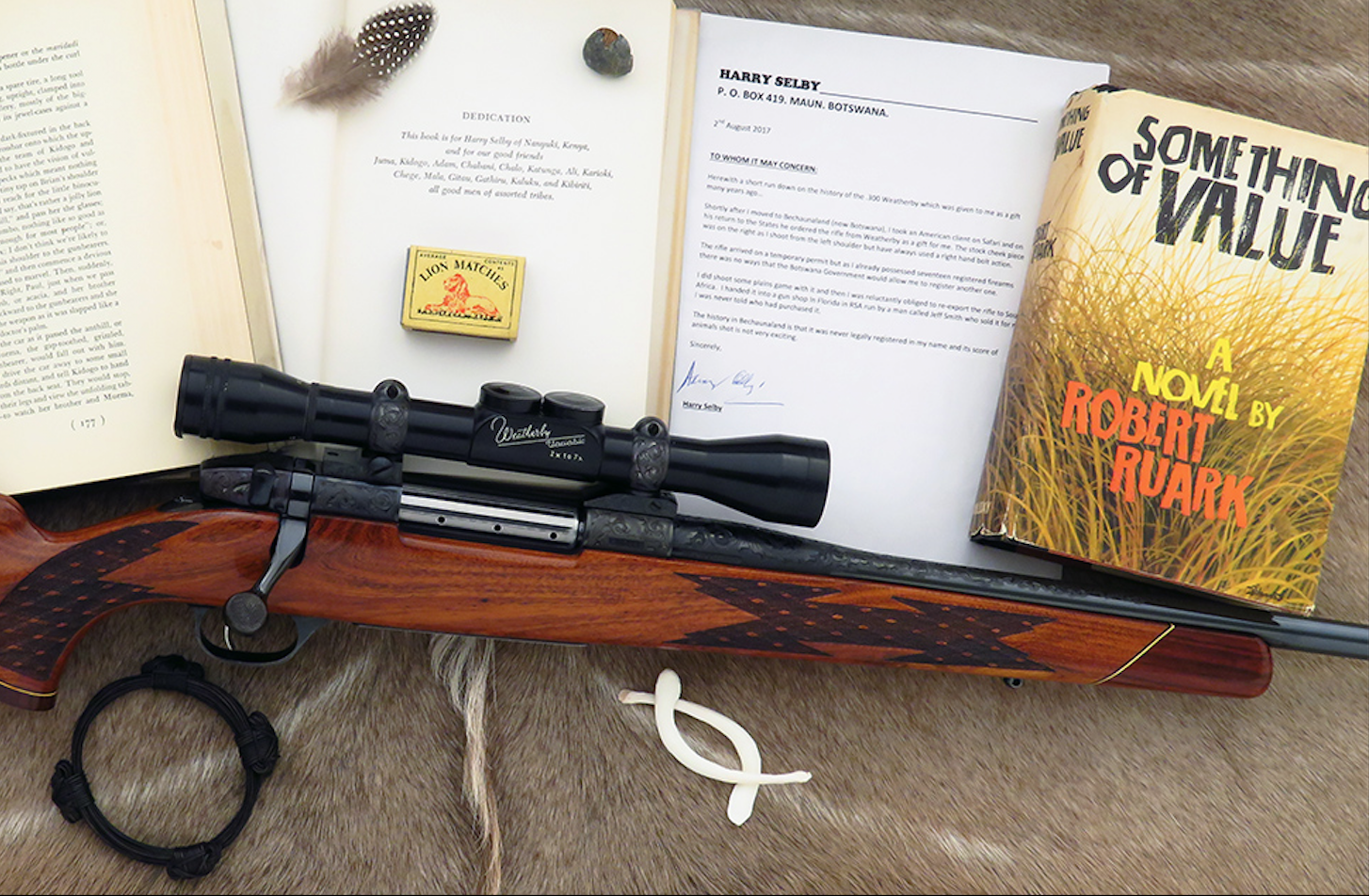

Paintings by Dino Paravano are part of the permanent collections of several noted museums, including five at Leigh Yawkey Woodson. In addition to original oils and pastels, he has illustrated several books, including two by Peter Hathaway Capstick and the recently published Hunting in Botswana, a major work by Tony Sanchez Arino (Safari Press).

Altogether, the ever-lengthening list of Dino Paravano’s accomplishments does read like an entry in Who’s Who. As for his paintings — they speak for themselves.

Featured on these pages are more than 280 paintings dating from the early 1970s to today. You’ll join the artist on adventure-filled journeys across North America, Central America, Africa and Asia and discover a vast portfolio of wildlife, including lions, tigers, bears, white-tailed deer and more. You’ll enjoy his gripping and refreshingly honest accounts of the experiences that inspired his artwork. In his stories, Sieve shares his deep commitment to land and wildlife conservation practices and recounts his adventures observing, photographing and hunting his wild subjects. Buy Now

Featured on these pages are more than 280 paintings dating from the early 1970s to today. You’ll join the artist on adventure-filled journeys across North America, Central America, Africa and Asia and discover a vast portfolio of wildlife, including lions, tigers, bears, white-tailed deer and more. You’ll enjoy his gripping and refreshingly honest accounts of the experiences that inspired his artwork. In his stories, Sieve shares his deep commitment to land and wildlife conservation practices and recounts his adventures observing, photographing and hunting his wild subjects. Buy Now