My eyes are fixed on a partially submerged log. I’m in knee-deep current, my breathable waders keeping the sun’s heat at bay overhead and the chill away from my legs underwater. I lift my rod, let line zip, and drop the fly right where Tim Wade wants it. My cast passes guide muster, and he gives me a smiling nod with commands to hit the exact same spot again.

I think we’re both in the fishy moment until Wade hollers, “Ho, bear!” That’s when I know I’ve lost awareness, but he hasn’t. We’re both wearing bear spray, but I’ve forgotten about bears while concentrating on my fly entering a trout’s mouth.

“I make noise,” says Wade, North Fork Anglers owner and outfitter. “There’s no point in asking to get eaten by a bear.”

Wyoming’s North Fork of the Shoshone River is just outside Yellowstone National Park, the heart of endangered grizzly bear recovery. (Photo: Kris Millgate/Tight Line Media)

We’re fishing the North Fork of the Shoshone River near Cody, Wyoming. We’re just outside of Yellowstone’s east entrance where there are fewer crowds of people and still plenty of wild land. It’s hog heaven for grizzlies—and for Wade’s guiding business.

“Everybody wants to see a bear,” Wade says. “They just don’t want to see it close.”

He’s seen them close. The campground near our fishing hole doesn’t allow soft-sided tents, and food must be stored in bear-proof bins. Grizzlies are definitely nearby.

Tim Wade always carries bear spray while fishing. He’s used it twice on grizzlies within 10 to 15 feet of him. (Photo: Kris Millgate/Tight Line Media)

“The old saying, ‘a fed bear is a dead,’ is very true,” says Scott Christensen, Greater Yellowstone Coalition director of conservation. “Bears that get into coolers and garbage figure out that that’s an easy food source, then they get into trouble.”

Wade doesn’t want trouble for bears or himself. He’s seen grizzlies along the river’s banks, but only twice within striking distance. In both cases, he sprayed pepper before paws made contact. Bear spray is on his hip as often as a fly rod is in his hand, and his shop is one of the largest sellers of bear spray in Cody. He runs the kind of business the Be Bear Aware Campaign champions.

“Responsible fishermen have little to worry about,” says Chuck Bartlebaugh, Be Bear Aware director. “Most of them have good outdoor skills. Attacks are more common among people going off-trail alone with no bear spray.”

Bartlebaugh carries two nine-ounce cans of bear spray when he’s in the woods. He teaches anyone within 100 miles of Yellowstone National Park how to use spray when faced with a grizzly; aim downward and out. The pepper cloud hits the bear . . . hopefully before the bear hits you.

“When the bear enters the cloud, it will feel the effects of the active ingredients on its mouth, throat, and lungs, displacing oxygen to the heart and muscles and stopping its ability to woof and growl at you,” Bartlebaugh says. “Gets in its eyes and it can’t focus on where you are.”

Hip holsters for bear spray are common on the North Fork of the Shoshone River near Cody, Wyoming. (Photo: Kris Millgate/Tight Line Media)

As for focus, Wade has it. He yells, “Hey, bear!” and finishes the sentence with a lower-toned, “Now put your fly in that pocket of water above the log.”

I realize he’s not asking a bear to fish. He’s asking me to cast again. There’s no bear by us, at least not that I can see through my fish-colored glasses. Wade’s just making sure any unseen bear knows we’re in the area so it has a chance to leave before we run into it.

Gone is a quiet afternoon of fishing the Shoshone, but I’m on board with the noise Wade makes because quiet means bears can’t hear us coming. When the willows around you are much taller than you and the beast in those willows is much bigger than you, you want the bears to beat feet before you see them.

Hey bear, ho bear, here I come. Be on your way.

Kris Millgate is an outdoor journalist based in Idaho Falls, Idaho. See more of her work at tightlinemedia.com.

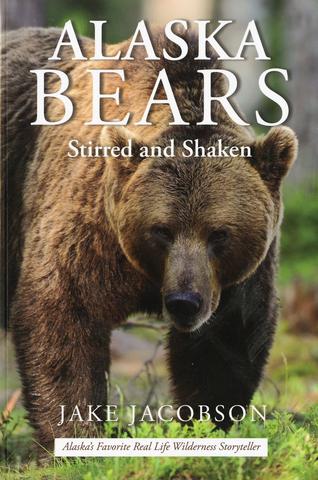

ALASKA BEARS: Stirred and Shaken is a collection of 24 stories describing Jake’s personal experience hunting and guiding for all the species of bears in Alaska. Bear biology, hunting techniques, cabin depredations and avoidance thereof, and other aspects of bear pursuits are detailed. These are true stories except for the names of some of the hunting guests from Jake’s fifty years of living and hunting in Alaska. Buy Now