Properly tied, these streamers possess an inherent action, their materials moving enticingly even in the slowest of waters. However, their true potential is only realized when the angler imparts them with life-like darting and holding motions during the retrieve. Indeed, fishing the streamer well is a dynamic activity where one can truthfully say, “The more action one gives, the more action one gets!”

Although such streamers have been used throughout the land, nowhere else have they been elevated to a higher artform than in the Rangeley Lakes region of Maine. There, deep in logging country, a number of brilliant tiers have provided visiting ‘sports’ with trophy-taking streamers for more than a century.

One tier, however, stands alone above all the rest, a woman who didn’t tie her first fly until age 38, but who would go on to become the acknowledged genius of the craft: Carrie Stevens.

Records show that Carrie was born in Vienna, Maine, in 1882, but little else is known of her early years until her marriage to Wallace Clinton Stevens in 1905 and their subsequent move to the Rangeley’s Upper Dam more than ten years later.

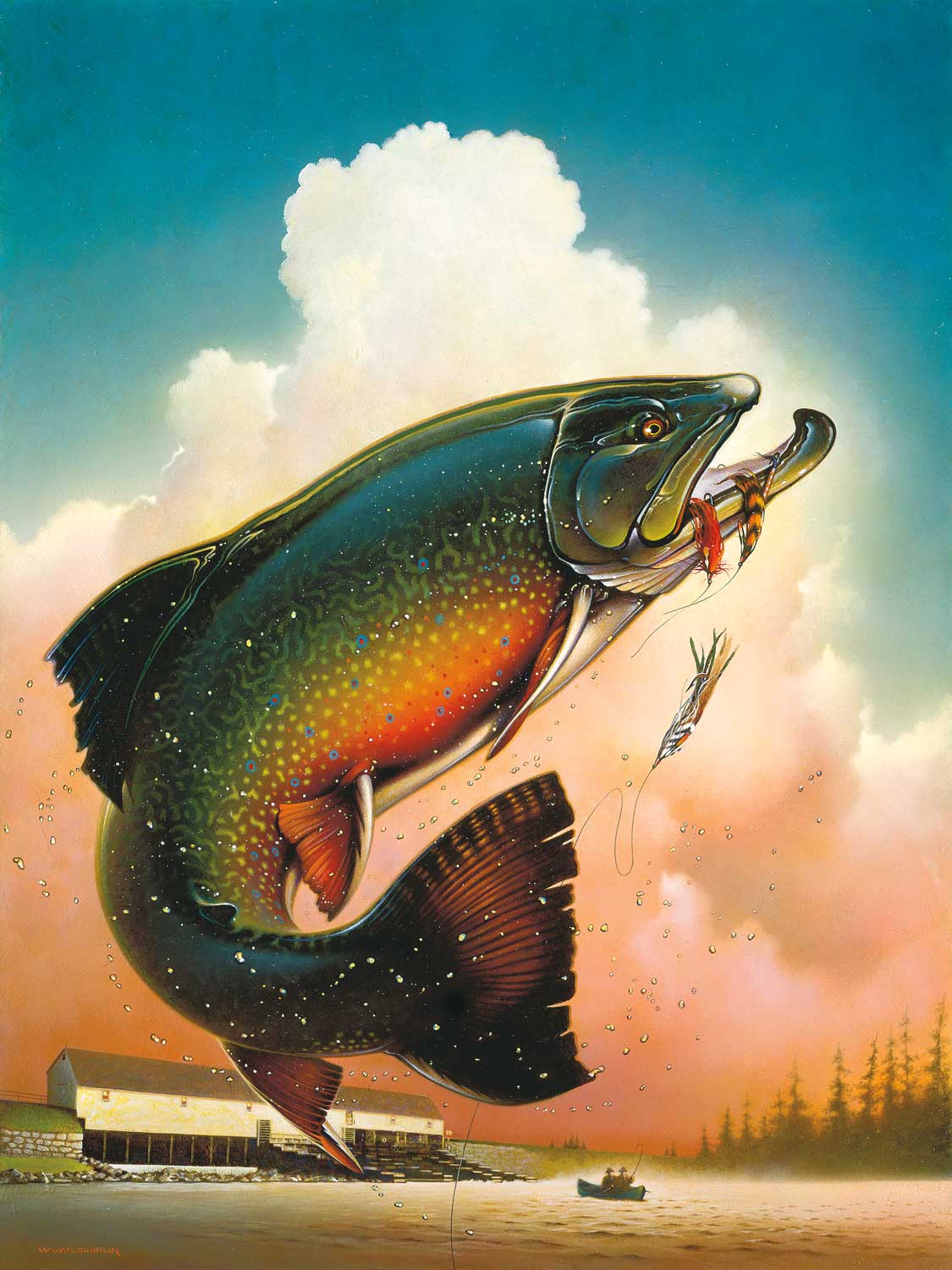

The author’s painting of White Nose Pete leaping high above the waters of Upper Dam Pool.

That remote area, long popular with sophisticated fishermen from as far away as Boston, New York and Philadelphia, was the perfect environment for an outdoorsman as knowledgeable as Wallace, who by 1920, was one of the most sought-after guides. It would be a casual suggestion from one of Wallace’s clients, “Shang” Wheeler, a premier decoy carver, that would forever change Carrie Stevens’ life.

Sending her a blue-and-white bucktail and feather streamer tied on a long-shanked English hook, along with a collection of loose materials, Wheeler recommended she try her luck on the Upper Dam Pool. He added that she might even consider tying some flies of her own. Intrigued, Carrie acted upon the suggestion after augmenting her modest supplies with some tinsel, rooster hackle and bucktail. Though lacking any training in fly-tying, she simply used common sense and her own artistic talents to tie her first fly. That fly would eventually evolve into a collection of streamers known as the “Rangeley Favorites.”

Over the next few years Carrie continued to experiment, developing new patterns and tying techniques on streamers used by Wallace and purchased by other guides and “sports.” Word was getting around the camps: “Those Stevens’ flies work!”

A Gray Ghost tied true to Carrie Stevens’ original pattern by Leslie Hilyard.

On July 1, 1924, four short years after Carrie’s introduction to fly-tying, an event occurred that would quickly propel her name to the top of the fly-fishing world. It was a sunny day and Carrie decided to fish the Upper Dam Pool, situated just down the portage path from her home. Built between Lake Mooselookmeguntic and Upper Richardson Lake, the Upper Dam’s swirling tail-waters were long known to hold trophy brook trout, the glorious prize sought by clients who cast for them from boats rowed into position by guides.

Choosing to fish from the apron of the dam, Carrie, alone with her thoughts, had only been casting for a short time when the fish struck – an enormous brookie. The ensuing battle would seesaw back and forth for one nerve-wracking hour before her catch was at last brought to net. Carrie was elated!

With the fly still firmly in the trout’s mouth, Carrie ran to the hotel that overlooked the pool where the fish was immediately weighed. Her brook trout came in at 6 pounds, 13 ounces, the largest taken from the pool in 13 years!

Carrie’s wonderful catch was entered in Field & Stream magazine’s 14th annual fishing competition, in which her fish was the second largest brook trout taken in 1924. Carrie’s second place prize was an original oil painting by famed sporting artist, Lynn Bogue Hunt! That was only the beginning.

A subsequent story appeared in the September 1925 issue detailing Carrie’s adventure and revealing that the spectacular fish had fallen to a pattern of her own design. Orders for Carrie Stevens flies began to pour in and her renown was launched.

In the early portion of her tying career, Carrie’s patterns were affixed to cards and simply identified by a number. That would change as she gained confidence and the realization that her flies were indeed special, unique in both their design and construction.

Authentic Gray Ghost tied by Carrie Stevens and owned by Leslie Hilyard.

She thus began to name her flies – Shang’s Special, Witch, White Devil, Don’s Delight and Gray Ghost. Some names were fanciful (Water Witch), some were descriptive (Green Beauty), and a great number were named for people, many of whom were personal friends or favorite clients of Wallace. As a commercial tier, Carrie also understood the value in tying flies to commemorate a national figure (the General MacArthur), a significant event (the Victory) or even to flatter a customer. Clearly, basic marketing was not lost on the gentle lady at all!

Carrie’s flies didn’t just produce, they produced astonishingly well. As her biographer, Graydon Hilyard, attests, “Of the 173 record fish taken from the Upper Dam Pool during the 1930s, forty-nine percent were caught on Stevens’ patterns.”

With an outstanding performance record like that, Carrie’s fame continued to grow and she became the subject of newspaper interviews and even more magazine articles. Countless angling celebrities of the day chose Stevens’ flies and orders began coming in from around the globe – the fishing hotspots of Europe, South America, Australia and New Zealand.

Carrie met the ever-increasing demand as she would throughout her career. She tied alone, never hiring help or ‘letting out’ orders to other tiers. She simply sat in the front porch of her cottage quietly producing masterpieces, the head of each finished with her signature colored band.

Her phenomenal career would soar through the 1940s until late 1949. Then, the loss of many close friends coupled, with the burden of age and ill health, finally caused Carrie and Wallace to sell their wilderness camp and move away. They would spend their remaining years in Madison, Maine. Upon her retirement, her business, “Rangeley Favorite Trout and Salmon Flies” would be sold to H.W. Folkins in 1953, who in turn sold it to Leslie Hilyard in 1996.

Should you travel to the Upper Dam and walk the few hundred yards down the old track to Carrie’s house, you would see the fine plaque erected by her friends not far from her front door. It reads in part:

“Mrs. Stevens practiced her art here for nearly three decades. She originated at least 24 streamer patterns and tied thousands of flies for countless sportsmen. She never read instructions on how to tie a fly, never saw one tied by another person, and though many watched her at work, no one ever saw her completely finish one of her streamers.

This tablet is placed here to honor a perfectionist and her original creations – which have brought recognition to her native state of Maine and fame to the Rangeley Lakes region.” August 15, 1970

Carrie passed away just 12 days before the dedication of the plaque and the proclamation by Maine’s Governor Curtis that the day be known as Carrie Stevens Day.

Gracious, warm-hearted and supremely talented, Carrie had never left her beloved Maine. Instead, the world had come to her.

Author’s Note: For an in-depth, beautifully presented look at countless Stevens patterns and their proper tying techniques, along with period photos of Carrie, Wallace and friends, locate a copy of Carrie Stevens by Graydon and Leslie Hilyard. It is the source book on her life and work.

THE GRAY GHOST

Without a doubt, Carrie Stevens’ most famous streamer pattern is the Gray Ghost. Created in the early 1930s, it quickly garnered international acclaim and to this day is available in virtually every fly shop and outfitter catalog in North America . . . or is it?

Certainly, streamer flies are sold by the thousands annually under the Gray Ghost name, yet none of the commercially tied examples I purchased from multiple sources followed the unique construction techniques developed by Carrie. Not only did proportions, color and material selection vary widely, but in every case the most critical stage of the fabrication was invariably omitted: gluing the fly’s shoulder feathers to the wings. A minor detail? Hardly, for that omission eliminates the most significant contribution of Carrie’s tying genius and, ironically, removes all of the exceptional action resulting from her tying approach. It’s the gluing together of those components that causes the first third of the fly to remain rigid, creating a perfect baitfish head profile while the remaining two-thirds of the streamer is soft, highly flexible and free to undulate with an enticing grace. How ironic that the very action which made the original Gray Ghost a fish-taking phenomenon is thus rendered non-existent!

Will today’s diluted copies take fish? Sure, even the crudest of flies will take some fish, but as an experienced streamer fan, I’m convinced that a properly tied Gray Ghost will out-produce today’s simplified offerings by at least three to one, and probably closer to five to one.

How does one get a “true to pattern” Gray Ghost? Contact a talented fly tier in your area and tell him you want exact copies of the Gray Ghost, including the use of golden pheasant and jungle cock feathers . . . and that you are prepared to pay. Price per fly will vary with the tier’s reputation, but I would not consider $25 each unreasonable, particularly when one considers that Carrie was charging $1 each in 1950!

Invest in a few and you will quickly understand what made her original Gray Ghost a classic; they are beautiful, durable and most importantly, they work! My favorite source for Steven’s patterns: Leslie Hilyard of Ipswich, Massachusetts.

WHITE NOSE PETE

The Rangeley area has produced legends for more than a century – celebrated fly tiers, guides, taxidermists, authors and anglers. There is also a legendary fish, a massive brook trout known as White Nose Pete, whose earliest encounters with the fly fishing fraternity date back to the 1890s. This demonic denizen of the Upper Dam Pool prowls the depths unchallenged, his great hooked maw festooned with streamer flies, pathetic pennants of battles lost by anglers whose tackle and skills were no match for the wily brute.

Although the subject of fireside tales, poetry, outdoor writers’ hand-wringings and even a decoy carver’s humorous hoax, I simply regarded Pete as a local fabrication, a publicity gimmick invented years ago for the enchantment of visiting sports, but then he struck again, on June 13, 2010.

I had taken several salmon from shore when my host, Graydon Hilyard, motioned for me to join him on one of the “piers” jutting downstream from the dam.

“Use my rod, Wayne, I just tied on a Gray Ghost.”

“Thanks,” I said, as I tossed the fly into the edge of the whitewater. There was an immediate hit!

“You’re quite a guide,” I laughed. Then all hell broke loose!

The entire fly line smoked through the guides, followed by 90 percent of the backing before the fish finally slowed! Graydon was cheering while other anglers on the dam stopped fishing to watch.

Twenty minutes passed before I managed to get any fly line back on the spool, and then came another violent, head-shaking run equal to the first! We eventually lost count of the runs.

After 45 minutes, another angler joined us, “Use my net,” he shouted. “Yours is way too small!”

An hour and a half later I seemed to be winning with nearly all my line back on the reel, then something changed. The power was gone, yet I still had a fish on. There, at the end of my line was a well-hooked 12-inch salmon. What?

We all stared for a moment, then understood what had happened. The salmon had hit the Gray Ghost and was himself immediately taken – whole! The culprit could only have been a brook trout – a brookie in the seven- to nine-pound range that was eventually wrenched off my “bait” in those last few seconds by the force of the current.

“In all my years here, I’ve never seen anything like that,” said Graydon. “You’re now part of the Upper Dam lore because you just fought White Nose Pete! He won, but you played him beautifully!”

While the other witnesses were just as complimentary, the truth came out over a fireside scotch that evening when Graydon intoned, “You realize, Wayne, that you lost the fish of a lifetime . . .”

RANGELY OUTDOOR SPORTING HERITAGE MUSEUM

In addition to the region’s terrific fishery and spectacular scenery, another delight awaits the visiting sportsman: the Rangeley Outdoor Sporting Heritage Museum. This national level facility houses a treasure trove of artifacts documenting the extraordinary impact of Rangeley men and women on the world of fly fishing.

Some museum highlights:

Watch archival film from the early 1900s depicting intrepid “sports” as they arrive by steam train and launch, each gear-laden gent eager to battle with the giant brookies sought in these waters since the Civil War.

Action shots show the sports and their guides as they cast (and catch!) from the iconic Rangeley boats, elegant craft designed specifically to ply these waters.

Check how their luck was running as you peruse decades worth of logbooks from camps such as the one at Upper Dam House where brookies under three pounds were not even counted! Reading the names, dates, flies used and creel weights makes their experiences come alive and your own imagination soar – especially when seeing such jaw-dropping entries as a brookie that tipped the scales at 11 pounds, 2 ounces!

There are vintage fly rods, reels and assorted angling paraphernalia aplenty, along with spectacular trophy fish mounts, paintings and carvings from such greats as Herbie Welch and J. Waldo Nash.

You can marvel at the works of many talented tiers, including Carrie Stevens, whose skills are evident in a display featuring pristine specimens of more than 100 Stevens’ patterns. They are perfection.

Surprises abound when, for example, one discovers that an area lass named Cornelia Thurza Crosby (1854-1946) was Maine’s first registered guide! Known as “Fly Rod Crosby,” she was a huntress, author, friend of Annie Oakley and as hard core about fly-fishing as any man today. She once proclaimed: “I would rather fish than go to Heaven!”

The Rangeley Outdoor Sporting History Museum opens a wonderful window to those “golden times,” enabling you to look back at the gifted people of Rangeley whose efforts contributed such an effective addition to our sport – the eastern streamer fly.

Note: This article originally appeared in the 2011 March/April issue of Sporting Classics magazine.