The artistic images that come from these artists’ experiences become a visual bond between all of us who love nature.

An artist in his or her lifetime may create hundreds of images, pouring hours of creativity and years of experience into each piece of work. Yet somewhere within the deep recesses of their being, one image lingers paramount. Maybe it’s something they’ve never put to canvas, but it nurtures their artistic souls. It’s an experience that turned them into dyed-in-the-wool naturalists or inspired them to creative endeavors as a lifestyle. The poignancy of that one event hovers a wingbeat above all others.

Mine came years ago when I was just starting as a professional artist in Alaska. I’d given up teaching to pursue life along the fringes of civilization within a stone’s throw of moose and grizzly bears. By then I had been charged by moose and stalked by grizzlies, but none of those experiences compared to that cold autumn morning along the high tundra bluff overlooking the Nenana River. I was awakened by a pack of wolves noisily coursing along the lower part of the valley. I heard them beyond the fringe of trees that surrounded the small clearing where I lay huddled in my sleeping bag, frost rimming the rocks on my now dormant fire pit. I propped myself on my elbows, cupped my hands to my mouth, and gave my best wolf howl.

Five wolves soon appeared at the edge of the clearing only 50 yards away. I howled again, and one wolf advanced in my direction, and looking directly at me, echoed my howl. I howled again, and he answered. While the others searched the underbrush for voles, this one wolf and I carried on an intent conversation, matching each other howl for howl. The wolf continued to move closer, finally stopping about 20 or 30 yards away His eyes were deep, as if I could see clear into his soul. After 10 or 15 minutes, he turned and followed the others down the slope and into the brush. Though I wasn’t in any way threatened, I felt this was the first time a wild creature actually tried to communicate with me.

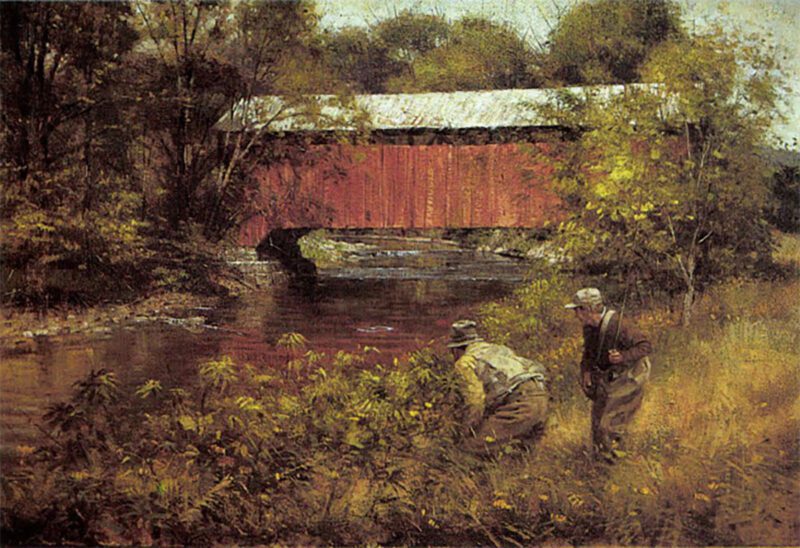

Bob Abbett’s captivating oil of two fishermen Stalking the Brown.

Later, I wondered if other artists had been inspired by encounters with wild animals. Of the many tales I’ve heard, four stand out — three from prominent wildlife artists and the fourth from a young up-and-coming painter.

Bob Abbett of Bridgewater, Connecticut, speaks eloquently of that sense of anticipation we all feel when we slip into our waders and move cautiously through dappled light to the edge of a trout stream.

“In addition to showing the peak of an activity,” Abbett says, “I’m also attracted to the quiet moment, that interval of silent anxiety and communication between the principals that occurs just before the action breaks loose. It can be almost palpable, and as often as I’ve seen a bird flush or a fish rise, I can still feel a rush, and a kind of completeness as the several ingredients of the game all come together.”

Abbett continues: “That’s the way it was in Stalking the Brown. The absolute tension that occurred when my two friends began their ‘hunt’ for fish. The feelings in me were so strong — the hazy summer sun and the relaxed surface of the Aspetuck playing against the apprehension of the stalk in the presence of their quarry — that my need to paint it was stimulated toa level I could never resist.”

Leon Parson touches upon the sensitive side of outdoor experiences. It shows in his paintings and even in his magazine illustrations. All have the depth and feeling of a thinking artist. He creates a heightened adrenaline flow in the hearts of people who view his oil paintings.

“One of my most exhilarating encounters with wildlife happened in November of 1988,” says the Idaho artist. “I was in Alberta photographing mule deer. All morning there had been plenty of cooperative animals, everything from delicately posed does to young bucks sparring with each other. I was lucky enough to sneak uphill through some thick timber and found a huge four-point buck still in his bed. I burned a couple rolls of film and managed to get as close as 15 yards before he got tired of me and left.

“I moved away to a clearing in a patch of quaking aspen and started filming a doe. All of a sudden a huge buck came running into the clearing and stopped about 30 or 40 yards away! He was worked up and nervous and looked over his shoulder. Then he spun around facing the direction from which he’d just come, and a second monster buck came into view! The one closest to me laid his ears flat and raised the hair on the back of his neck straight up like a zebra. I was in the process of telling myself ‘they’re gonna fight,’ when they lowered their heads and charged. SMACK! CRACK! They were a blur of horns and hair! Then CRASH again, and push, shove, pull back, and do it again!

“The fight was mean, and I was astonished at the muscle/hormone power being exerted. I shot my last five or six frames of film. Then all I could do was watch. Eventually the biggest buck pushed the other backwards. They were tearing up dirt and brush like a couple of bulldozers. They fought their way to within nine steps of me! Unbelievable! A few seconds after that, one gave up and low-tailed it away, The experience left me stunned with excitement! It was absolutely exhilarating!”

One of the deer in Leon’s story is portrayed in his painting Backside of No-Tellum Ridge. The monster buck is in a somewhat more passive setting, but portrayed with all of the feeling that comes from having been there.

Nick Wilson of Payson, Arizona, often portrays a more gentle side of nature with his delicate medium of gouache. It’s not because his experiences have been any less exciting. “I’ve experienced many encounters with animals around the world, from the mock charge of an elephant in Kenya and photographing a huge blue whale in Alaska’s Prince William Sound to collecting butterflies in South America. Each event caused within me an overwhelming sense of awe and touched my heart.

“The encounter that probably had the greatest impact on my life occurred when I was just a boy of six. In a quiet pasture I saw my first woodchuck. Our eyes met for a second, then he scampered into his burrow. It was a simple event, one that most kids would have shrugged off and forgotten, but from it, I became a steadfast naturalist with the urge to draw animals.”

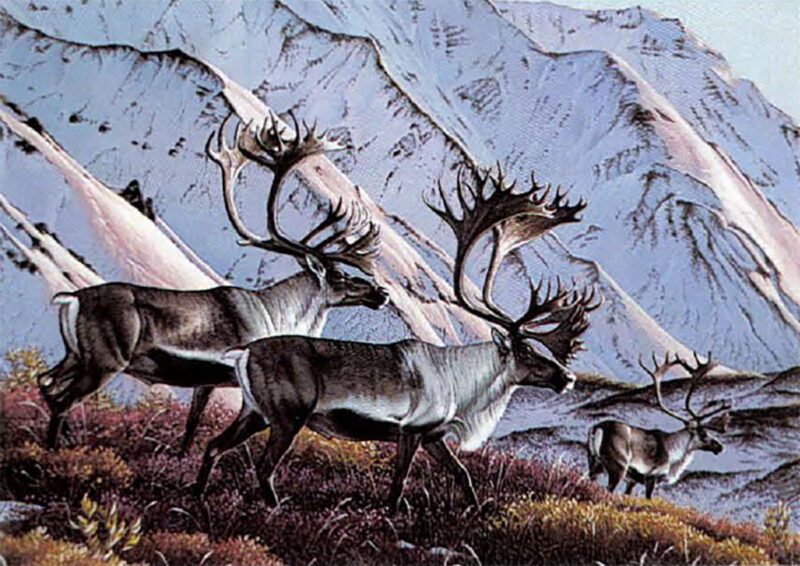

Cynthie Fisher’s portrait of caribou at Denali National Park in Alaska.

Nick adds: “I never attempted to portray that scene in a painting, though I remember it vividly I prefer to depict subjects doing things I could never hope to see in real life. I suppose it’s an expression of personality when invention takes the place of actual experience, so my work is strictly the product of my imagination.”

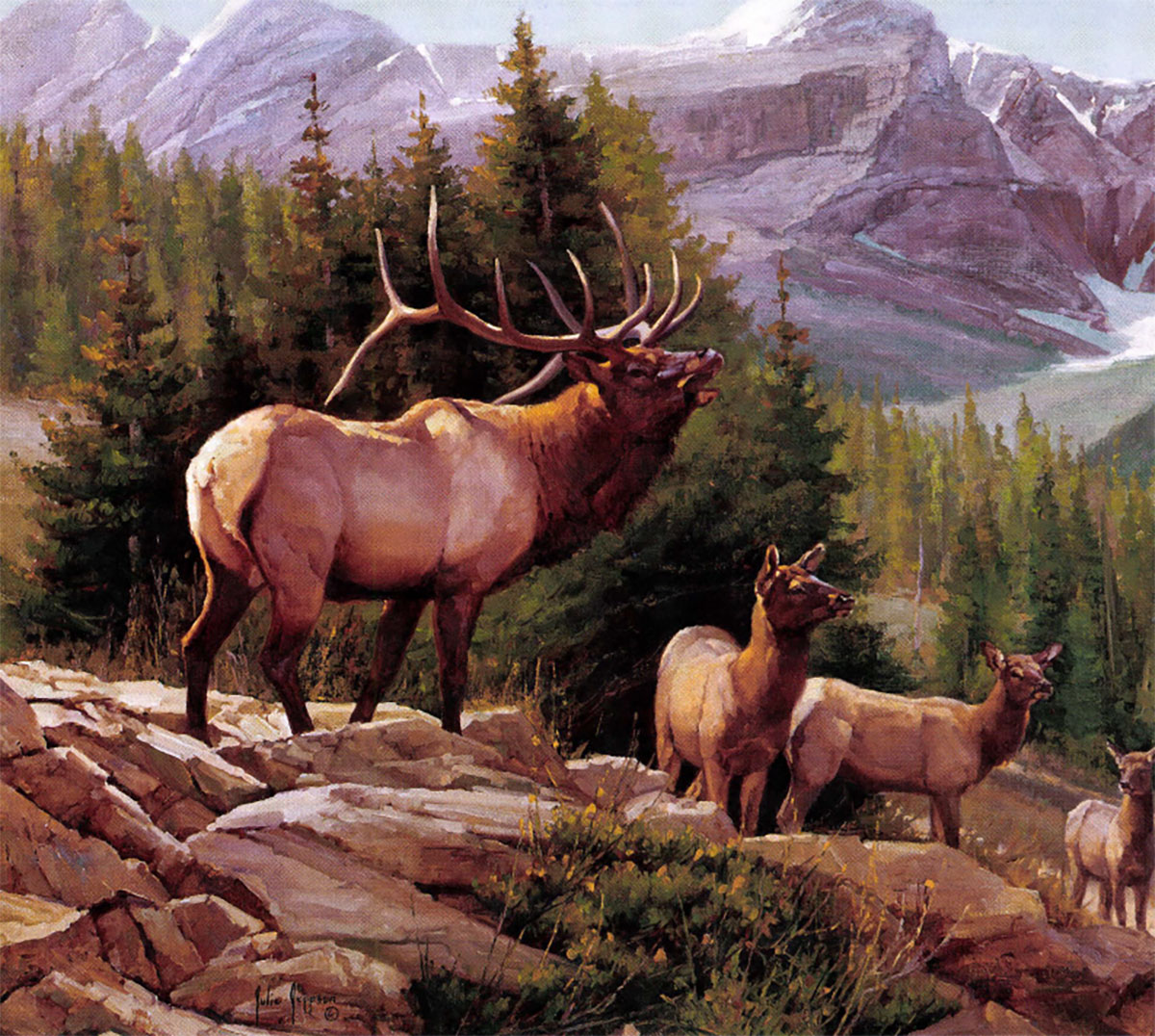

An artist who is rapidly gaining stature in wildlife art is Cynthie Fisher of Marblemount, Washington. Artistically, she’s far beyond her 28 years, a fact that loomed obvious when she placed third in the 1991 Federal Duck Stamp contest. Her art is strongly influenced by her outdoor experiences.

“Because of my dual interest in wildlife art and taxidermy,” says Cynthie, “hunting was a logical step for me. Being newly married to a seasoned hunter, I received three bits of wisdom prior to my first elk hunt:

1) Don’t shoot unless it’s a clean shot.

2) Always hunt uphill from camp, and

3) Before you pull the trigger, remember where the car is.

“On opening day in Colorado, I tried to imagine where I would be if I was a bull elk on a mountain with swarms of hunters after me. I decided that I would head for the steepest, nastiest ravine, so off I went.

“I finally struggled on hands and knees to the top of a steep slope and entered the thick lodgepole forest, where I stopped for a breather and a look at the new snow. My artist’s eye surveyed the surroundings as a potential backdrop for a painting. I heard a small snap off to my left, and suddenly two big bull elk walked out broadside about 30 feet away. Their ears and nostrils twitched as they tested the air, knowing that something was amiss in the woods. The light played off their golden hides and gleaming antlers, and they both stared directly at me for many seconds before taking a few bites of forage. The gun strap never left my shoulder. I forgot I even had it there (a sad fact I would never live down), but as I watched them walk deeper into the forest, I exhaled and marveled at the incredible sight. Three years would goby before I finally used that rifle, but that vision and artistic idea will always be with me.”

Any outdoor enthusiast can relate to these experiences. Even more importantly, the artistic images that come from such experiences become a visual bond between all of us who love nature. They’re opportunities for each of us to relive our own outdoor adventures as if looking through a window into our own personal world.

Similarly, when artists and fellow outdoorsmen gather about a campfire and stories are told, the artist soon picks up a pencil or brush and begins sketching. We’re reacting to any suggestion of shared experiences and compelled to the visual expression of it. In these ways, we try to make our wildlife portrayals into the essence of all that we share. They are important links not only to our natural heritage, but to each other.

Editor’s Note: This article originally appeared in the 1991 Sept./Oct. issue of Sporting Classics.

The Sporting Life is a celebration of gundogs and horses, hunting and fishing as expressed through the rich and exuberant paintings of Joseph Sulkowski. Limited 350 Deluxe Edition Leather-bound, Gold Embossed Cover Signed and numbered by Joseph Sulkowski, and 240 pages featuring more than 180 paintings. Buy Now

The Sporting Life is a celebration of gundogs and horses, hunting and fishing as expressed through the rich and exuberant paintings of Joseph Sulkowski. Limited 350 Deluxe Edition Leather-bound, Gold Embossed Cover Signed and numbered by Joseph Sulkowski, and 240 pages featuring more than 180 paintings. Buy Now