Dig the sun from the sunset? Retrieve the river from the sea? Beg back a life that has been wrestled to the grave?

For a great part of our being, we are drawn against a metaphysical world of imponderables, an ethereal vacuum of longing, where hope is scarce and disappointment is supreme.

Thus we are driven to wander, searching for something of essence that can be real. Something to fill the void, to make life better the living. Discovering, that in the alter-world of material means, it is sometimes possible . . . if someone promises himself deeply enough . . . to bridge the chasm to yesteryear. To draw back the curtain on the past, to reach in and usher to life, again, something beloved and departed.

Almost always our method ascends to the arts: the inspired expression of human aspirations and doubts, driven and guided by the creative demons that torture men’s souls.

To such obsession we owe much of our spiritual foundation, and the largess of our imagination . . . and the vast body of mystic, worldly treasures we hold to be sacred and extraordinary.

So it was, that in 1994 – when maybe no one at large really expected it – an inspired and resourceful Italian by the name of Antony Galazan was driven to gift to the gunmaking art the return of the Ansley H. Fox shotgun. Not a reproduction. The real thing. Arguably better than the original, picking up on the Philadelphia serial numbers from when the last gun was shipped 64 years ago, four years after I was born.

From that moment, first to myself and later to the man himself, I said, “Tony, one day I want you to build me a shotgun.”

“I’d love to build a gun for you,” he said.

“That’s what I do,” he said. “I build guns.”

Oh, but doesn’t he.

I was born a century late.”

As a shooting man, in the company of my fellows, I have heard it. Said it. Believed it.

For I was brought into this world among shooting men, many of them born in the century before me. Men who told stories in the few years before they were gone: tales of fabulous field sport and brilliant dogs, of exquisite quail lodges, geese over pit blinds, ducks on the big water or high in green timber.

A bevy of the author’s favorite setters and spaniels, the new Fox gun and old-fashioned promises to keep.

Men who carried smoothbores, side-by-sides: Parkers and Foxes, Lefevers and Ithacas and Smiths. America’s Best. Exquisitely balanced little bird guns and great, heavy waterfowling pieces. Sweet, open 20s and awesome, over-bored 12s. With fabled names like Thomasville and South Georgia attached to them, Mattamuskeet and Currituck, the Chesapeake and the Eastern Shores. A few, even, handsomely adorned with the game they sought, and the dogs they were pulled over, midst rich, fine scroll, with even the initials of their owners in old script on a gold oval at the toe of their figured walnut buttstocks.

I watched and listened and dreamed.

A fine gun to me then was an American Best – even a Vulcan or a Sterlingworth – because it was synonymous with the folks and things I loved best, and because that’s what they held to be best. I knew nothing of world bests: the grand, bespoken guns handcrafted on Audley Street, nothing of the multitude of fine shotguns from Spain and Italy and Scotland that would grow out of the double gun resurgence at the nearing of the Millenium. Even as I did, nothing really changed. Though I appreciated them immensely, they embodied little of beginnings, little of the old shooting men I knew, little of home.

Almost seven decades have passed, and in many ways – with almost every word I put to paper – I guess I’m still trying to go home. Except that now, home is not only the woods and streams of the small farming community I came up in, but the vast landscape of shooting adventures . . . dogs and men, upland and marsh, near and far . . . it set me to.

Through all, though I first craved a Parker, it has been the Ansley Fox gun that I have come to love best, that has most especially captured my fancy. That has surged wonderfully back, so many times, across the years. When first I walked alongside Murray Hoover, the most renowned bird-hunter in our small neck of the woods, when later I read Havilah Babcock, met Nash Buckingham and “Bo Whoop,” relished Teddy Roosevelt’s African safari and acquired my first “C” Grade Philadelphia original – all my heroes shot a Fox.

But it’s deeper. All my life I’ve loved foxes. The beauty, stealth, wiliness and fascination that is Reynard. I have known him well, you see.

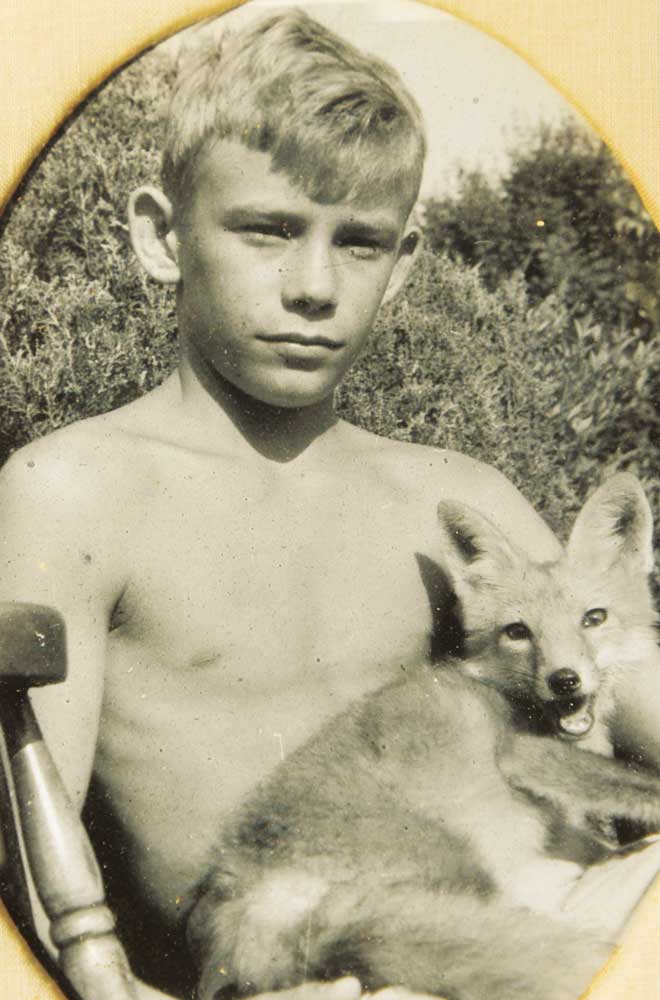

When I was 9, I worked part-time as a kennel boy for a local veterinarian. One day a client came in cuddling something small and fuzzy in his jacket. It whimpered softly, and mewed, kinda like a kitten. Finally, when I could stand it no longer, the man parted his coat. It was a gray fox kit, and for me, love at a heartbeat. For I was utterly taken by anything wild, and especially by the thought of touching it.

Later, when the man had turned to leave, I could not endure the parting.

I was a shy lad, taught to speak when spoken to. Not then.

“Mister,” I said, “would you think you could part with your fox?” And he saw the desperate longing in my eyes.

He pondered a moment. “Well . . .” he said, “five dollars and found, and he’s yours.”

Five dollars was a bunch of money. So, in despair, I turned to Doc Kelly, who sat next to God, and meekly begged a week’s advance on my kennel pay.

At first he looked down his nose at me, sorta like all bosses look at an underling when money’s in hock. Then he smiled, pulled his worn leather billfold from his pocket . . . turned his back . . . and when he turned back around, handed the man a bill with Abe Lincoln on it.

The man passed the fox to me, which turned out to be a little vixen, and my grin was bright as a sunbeam. The rest of the day I carried her inside my own jacket while I finished my kennel chores. Doc wanted to give her a rabies shot, “or else he’d have to give me one when she bit me, which she would.”

But I said “no, we’ll just have to get ’em at the same time, cause she’s too little now.”

I named her “Lorrie,” and she ate and slept with me, and wagged her tail at me like a dog. Whined and danced for me when I got home from school. Word got around about a boy and a fox, and folks started bringing me others, out of slab piles and den holes. They’d destroy the den, the female and the rest of the litter – cause they were hardscrabble chicken farmers – bringing me the sole surviving kit.

Before long I had a young red fox to go with the gray. I named her “Lou,” after my Aunt Louise, who was an artist and who painted a portrait of me with her. Then came another gray. And now they all ate and slept with me, ’til Mama was afraid to come into my bedroom.

That’s how I earned the nickname “Fox,” which my folks called me until I was well-on a man.

Through the years, I marveled at foxes in the wild, watched them hunt; always at heart they were my brothers. Despite their predatory habits on hen-houses, and the wild things humankind considers proprietary, like rabbits and quail, I made a vow never to shoot one – and haven’t. And won’t. I don’t shoot nobody for trying to make a living. Particularly canine nobodys.

There’s a lot more to the story, but that’s the gist of it.

And Doc Kelly never did give me a rabies shot.

Then, lo and behold, it all came tumbling down right-side-up when Antony Galazan resurrected the Fox gun.

Cause, God, at the hours I had spent in my teens – pouring through a 1923 Ansley Fox catalog until it was ragged and almost illegible. Memorizing every page, all the guns – lock, stock and barrels. Everything about Krupp steel and Circassian walnut, grade-by-grade checkering and engraving, Kautzky triggers and skeletal butt plates – for “the finest gun in the world.”

Cause “A Fox Gets The Game.”

Most particularly, I coveted the thought of an “FE,” so incredibly exquisite from the picture. That according to the factory you could have “built specially to order,” if you’d just write down the specifications you wanted. But it had cost a half-a-thousand even back when, and what’s more, there was reputed to have been a “G” Grade – all the more magnificent – that nobody anybody knew had ever seen before that would set you back a full grand.

I would sit for hours, dreaming of how marvelous it would have been to be rich, with money to spare, and to have been able to sit down when the Fox Company was still afloat and draw up the specs for a special, one-of-a-kind gun. That you have your dogs inlayed in gold on, with grouse and quail embroidered in scroll, the stock fitted to your dimensions, and your initials on a gold shield so everybody would know it was yours.

Cause my Aunt had promised me: “One day, Fox, you’ll have a Fox gun. Of your own. Finer, even, than the Sterlingworth of your Uncle Sid’s.”

But I never saw how, for the Ansley Fox Gun Company had gone belly-up a fair while ago, and Tom Henry at the General Hardware didn’t deal in Fox guns any more, and there didn’t appear much chance of them ever coming back.

Until Jobe and Jerusalem, all the years passed, and along came Antony Galazan and dug the sun from the sunset.

“One day has come,” I told Tony Galazan at the 2009 Safari Club International Hunters Convention in Reno. “I want you to build me a gun. A Fox.”

I was far from a wealthy man, but I’ve never been poor on dreams, and I’ve tried hard not to let life or poverty get in the way of scratch and means. I had decided, at 67 – before it got any later – I was simply making the Fox a life’s priority. I planted another hill of potatoes, and my woman – like she has all the years – cut another hole in her apron, and cinched it down a mite tighter over her faded jeans.

Tony smiled, said. “That’s what I do. I build guns.”

Ugh . . . huh.

Suddenly I was 17 again, pouring through possibilities again, cause I was about to put together, at long last and dream’s-end, the specifications for a custom Fox gun. Except somehow, someway – like my Aunt had promised – now it was real. Now the options were wonderfully broader than before, than ever they’d been even, with the original Fox Company.

I started to call Mike McIntosh, because I knew he would celebrate with me, maybe solicit a little advice – but then I said to myself, no, my man, this one is yours and there are six decades of shooting lore to pull from. It’s all about you, where you’ve been, and what you truly wish in a shotgun.

A few of the author’s favorite things: Ansley H. Fox #F206, 025; custom-built, silver wire-inlaid blade by Jay Hendrickson; braid-and-brass whistle lanyard by Knotsmith, a gift from Tom Davis.

Because my supreme reason for this gun was to consecrate and commemorate a lifetime of upland shooting adventure. To enshrine my shooting soul, all that I love. Fifty-one dogs of my own here and gone, scores of others I have known and enjoyed, guns and gunning companions now and when, golden autumn uplands and snow on laurel, the glint of sunlight on whirring pinions, a day of birds hung against weathered barnwood, the soft, flickering reflection of evening firelight in honey-smoked walnut.

I’d shoot it a bit, over special dogs, special times. But I had other guns to shoulder, day in and out. This one was to have and hold. To pass along, so someone might know of the things I cherished most, when flesh and blood I’m gone.

I could have a lot of guns in the world, for what it would take. A lot of fine guns. And I thought about that. But come bedrock, it had to be a Fox. Not a Fox, my Fox.

On February 10, 2009, hands trembling, I took a long breath, then dropped the order in the mail. Postmarked Priority, CSMC, New Britain.

Oh, boy!

If you’ve never thought for or ordered a custom shotgun, and it’s in your blood to do, you should. It’s an experience unlike any other, replete with exquisite anticipation and ultimately, resplendent awe. What you’re venturing to create is a one-of-a-kind gun in the world, and all you have to do is think about that for a few moments, and just how truly special it is and will come to be.

I’d tell you also it’s one of the most lucrative investments you’ll ever make; just compare the fiscal performance of fine guns against the Dow Jones over the last 20 quarters. But then, every time I try to pass that off on Loretta, she tells me it’s a penniless argument, “cause it’ll never be sold. It’s stagnant money.”

Ah . . . well. A woman’s logic is like your reflection in the bathroom mirror when first you get up in the morning. Ugly sometimes, but there’s no escaping it.

Whatever the financial dynamics, which for any true lover of exquisite smoothbores are only important in the abstract anyhow, working out the specs and dimensions of a one-in-the-world gun is a happy thing. A little frustrating actually, here and there, like picking between having Christmas or Kate Beckinsale for your birthday party. But all in the good ways.

When all came to ground, you can see from the accompanying photos what I, personally, most love in an upland shotgun.

Starting with basics, it had to be a 28 bore, which is one reason I decided against an original Philadelphia gun, even in 16 or 20. There were no Philadelphia 28s, and the 28 is my favorite.

Dilemma one was the grade. I’ve always admired the XE tremendously in the original Fox line, but the combination of youthful slaverings over the FE, and the astonishingly beautiful Exhibition Grade guns Galazan has built in the last ten years led me to choke down the egg in my throat and go for broke. If you’re wondering, that’s no pun.

But, Lord, after all the years and tears, how could you not?

Barrels? Well, Krupp, of course. But 26 or 28? I lost a few nights’ sleep on that one, purely because of the looks and proportions of the gun. I wasn’t worried about balance. Galazan would augur that. Twenty-six inches has always been my thing in the woods; I like short and fast. I never see the barrels when I’m wingshooting anyhow. It’s all eye, hand and timing. So 26 it is. Ivory beads, fore and mid-ship.

Boring was easy. Skeet right, Improved Cylinder left. Less is best.

Double triggers. I just favor the look.

The wood I could have declared 20 years ago. Oiled, hand-rubbed, exhibition-quality Circassian, for Galazan has in inventory some of the finest blanks available anywhere. Color and figure? Honey and smoke for the base tones, medium dark. For heart and spirit, Nature’s angst: spectacularly figured crotchwood. For as long as I’ve loved fine guns, I’ve adored equally the strength and soul of stressed and strictured walnut crotchwood, all shot through with flames and feathers. It makes me warm inside.

That’s what I asked for, and as you can see, CSMC did a pretty attractive job of delivering. Splinter forearm to match, with a subtle and vintage Fox Snaubel, tipped in burnished buffalo horn.

Stock dimensions weren’t much of haggle either. I had shot with the late Jack Mitchell at Addieville East Farm a few years before, and between the tailoring he deciphered best, and a little interpolation against the measurements of the guns in my cabinet I have shot best all my life – the deed was done. Fifteen inches LOP, 1¾ of fall at the comb and 2¾ at the heel. A modest bit of cast-off to seal the deal. Oh, Sally, does it come up ever so sweetly.

The engraving I debated deeply: the delicate scroll and traditional patterns of the first generation Fox originals, particularly the style and mood of dogs and birds etched simply against the patina of hardened gray steel, versus the arresting drama and telekinetic artistry of deep-relief, ornamental scroll.

In the end, I decided for deep-relief scroll, against a French gray receiver, although originally I had specified bone-and-charcoal case colors. This was the only change to the original order. Turns out, when you case-harden a receiver under deep-relief scroll, the base tones eventuate very dark, and you greatly mute the boldness and extra dimension of the relief.

Rather than proceed rotely with my first wish, Galazan advised me of this and sent photos for comparison, which made the ultimate choice less difficult.

Now the broader canvas was done. Now I would declare it forever my own. For, it is through the final, eccentric ornamentation you choose that you have the opportunity to make a custom gun truly singular, render it wholly unlike another. That is why you begin. So that each time you will hold it, or look at it, it is at one with your soul.

Tradition and vintage style I would capture with seven gold inlays, each chosen to portray a particular fondness of my heart. I did not want the gun to be gaudy, but I wanted it to be rich in mood and statement. With all respect to the quiet and intricate elegance of simple game and scroll, I could not resist the beguiling gleam of gold. Nothing else ran as deep as my emotions.

The fox theme I wanted to carry far beyond the name of the gun. So on the right side of the receiver is a red fox, stealing toward a drumming grouse. The image of the fox is taken from the 1923 Fox catalog. On the left side, in an original image by the engraver, the fox is springing at the alerted and flighted bird, outcome uncertain.

Course, remember, “A Fox Gets The Game.”

Beneath and above the trigger guard, there had to be dogs. First, the portrait busts of spaniel and setter, joined at the shoulder, and facing opposite, to enshrine the two foremost and most beloved facets of my dog life. All those I have known and loved.

Immediately below, a bug-eyed setter before a small, hidden covey of quail. A jam find, for the birds are very close, and the dog is wont to move a muscle. The image I have coveted and saved for many years. It’s from an early Ithaca Gun Company catalog, actually, but Ithaca or not, it had to go on this Fox.

On the trigger guard itself is a still-life depiction of two hanging grouse. A day’s bag, against barnwood, you see. How I adore russet feathers against silvered barnwood. On the trigger guard extension is a small, roosted blue grouse. He’s at peace, as am I when I look at him. It’s the part of me that does not care to disturb him.

Last, not least, is the Gambel’s quail head on the top lever. A cockbird, jaunty and proud. I’m that way – I can’t help it – when I carry this gun. I hope with some dignity.

Finally, I admit to a bit of vanity. A gold oval bears my initials, and on the barrel rib is “Made for Me.”

So, now, Ansley H. Fox #F206, 025 has made the journey from fantasy to finish. It now has a life of its own.

I guess here’s how I feel about that:

Tony Galazan

Connecticut Shotgun Mfg Company

Dear Tony,

The Fox gun is, in a word, magnificent!

This purpose of this gun was to consummate and enshrine all the things I have loved in a fine shotgun, and indeed, in my upland shooting life at large, for the 67 years of my being. It does that superbly, and to you and the accompanying artisans at CSMC who created it from the rough notes of my dreams . . . my sincere congratulations and deepest gratitude.

The gun is the only element of the upland trilogy of gun, dog and bird that lasts the years. It alone survives, when flesh has been laid to grave, to consecrate and commemorate every wonderful and poignant moment of the shooting life that was one man’s all-embracing passion. Continuing not only with a life of its own, but as the embodiment of all those lives, human and canine – of all the wings and wonder – that passed before it.

A.H. Fox #206, 025 lives now, and will live on . . . and I find an unprecedented peace in that. Myself, fifty-one bird dogs, many happy hunting years gilded by golden days afield . . . they’re all there. I could not desire a more fitting remembrance.

With all regards,

Mike

Note: This article originally appeared in the 2011 January/February issue of Sporting Classics magazine.