No time to fart or fumble, on my belly with a beast that had tried to kill a man only the day before.

Willard Sumption had a buffalo ranch a little south of Aberdeen in that rolling country east of the Missouri breaks. Willard had one bad eye from the time two of his girlfriends showed up at the same party and one threw a stiletto shoe. Yes, some women wear high heels in South Dakota, if infrequently.

Willard couldn’t shoot worth a damn with only one eye, so when one of his bull buffalo went berserk and tried to kill him, he called Gordy Swenson. Gordy Swenson was a lineman for Otter Tail Power, a man who held lightning in his hands. In his spare time, he guided bear and boar hunters. Once he got that call from Willard, he was suddenly in the buffalo business.

Then Gordy called me. And then I was suddenly a buffalo hunter.

Buffalo dreams, bison nightmares.

Bison bison bison is not a buffalo at all, but a bison, as the scientific name subtly suggests. But as the average man is not likely to encounter either an Asiatic water buffalo or an African Cape buffalo, two equally disagreeable bovines, buffalo will suffice for common discourse.

Master of the Herd by John Banovich.

Bison bison bison was the dominant North American herbivore before Columbus; there was even the eastern woodland buffalo. Cherokees presented DeSoto with a hide in 1540—“an ox skin soft as a calf skin with wool like sheep.” Two hundred years later, Bishop Augustus Gottlieb Spangenberg, exploring on behalf of the Moravian Church near present-day Asheville, reported: “Tracks are everywhere, and can often be followed with profit. Frequently, however, a man cannot travel them, for they go through thick and thin, through morass and deep water, and up and down banks so steep that a man could fall down but neither ride nor walk!”

But alas, the eastern woodland strain, being no respecter of fences, crops or persons, was shot out of the Appalachians before the Revolution, though the animals’ migration routes, “buffalo traces,” are still occasionally visible in that high, wild country. Indians followed the buffalo trails, as difficult as they may have sometimes been, pioneers followed the Indians and, in 1773, built a town and a distillery where one such trail crossed the Kentucky River. Buffalo Trace bourbon is still made there to this day. Entirely passable tangle-foot, I am here to testify.

Buffalo dreams.

First reports of massive western herds were included in Merriweather Lewis’ report to Thomas Jefferson in September 1804, along the Missouri River not far from where Willard Sumption’s place is today. In his notoriously creative spelling and random grammatical flair, Lewis wrote:

First reports of massive western herds were included in Merriweather Lewis’ report to Thomas Jefferson in September 1804, along the Missouri River not far from where Willard Sumption’s place is today. In his notoriously creative spelling and random grammatical flair, Lewis wrote:

This senery already rich pleasing and beautiful was still farther hightened by immence herds of Buffaloe deer Elk and Antelopes which we saw in every direction feeding on the hills and plains. I do not think I exagerate when I estimate the number of Buffaloe which could be comprehended at one view to amount to 3,000.

Early homesteaders reported single herds thundering by their sod huts for three days and nights without interruption.

Bison nightmares.

From 60 million in 1850 to less than 600 a scant 40 years later, shot to feed railroad workers, shot to feed the cavalry, shot for their tongues and hides, shot to keep the Indians from eating them, shot and just left to rot. They were shot, shot, shot, their bones later picked and ground into fertilizer. It was a monumental slaughter, only rivaled by some modern wars.

Teddy Roosevelt won the Congressional Medal of Honor for his charge up San Juan Hill in 1898. He won the Nobel Peace Prize for ending the Russo-Japanese War in 1904. But there was no prize for his buffalo dreams.

In 1858, the year of Roosevelt’s birth, there were nearly as many buffalo in the United States as people. Roosevelt killed his first of two on a hunting expedition from his North Dakota ranch at age 26. By the time he became president at age 42, they were so scarce that the Brooklyn-based American Bison Society had begun shipping surplus zoo animals west to repopulate the Great Plains, with President Roosevelt serving as the Society’s first honorary chairman.

From that modest beginning, there are now more than 200,000 animals on private ranches in the U.S., with media mogul Ted Turner’s 50,000 head the largest private herd. There are 20,000 animals on public land, another 20,000 on Indian reservations, enough to be hunted again.

The 71,000-acre Custer State Park in South Dakota’s Black Hills has one of the largest public herds. Each September, some 1,300 animals are rounded up, penned, vaccinated, pregnancy-tested with some 200 animals culled and offered at public auction. But buffalo ain’t Herefords. Barbed wire can’t hold ’em, a nine-foot high corral of railroad ties and telephone poles might. Quite a rodeo—dust, bellering and cussing, Nikons and tourists from Japan. And this is where Willard Sumption’s bison nightmare began.

Willard went out to auction, bought a half-dozen heifers and cows and with predictable difficulty, got them funneled into a goose-neck stock trailer. Opening the trailer back at the ranch, he discovered one of the cows had delivered a bull calf in transit but had died in the process. Deep down in November and no wife to object, Willard struggled the 50-pound calf inside, built a pen next to the wood range and bottle-fed it till spring. Three years later, now topping a ton, the bull went rogue on a cold December day.

The bull hit Willard from behind, knocked him to the ground. The usual bovine coup de grace is either a trampling or a crushing, but the bull decided to plow snow with Willard instead and, in so doing, pushed him beneath the corral bottom rail. Bruised, shaken, but otherwise unhurt, Willard struggled to his pickup, drove home, called Gordy Swenson. The bull, meanwhile, broke through the fence, taking along two other bulls, a dozen cows and heifers as it lit out down the road.

We caught up with them daybreak the next morning. A foot of fresh snow overnight, but still it was an easy track. Every RFD mailbox, every farmyard gate post was broken off level with the frozen ground along the 10-mile route of the Great Escape.

The renegade buffalo were knotted upon a windblown pasture hill a thousand yards from the road, the barbed wire between us and them flayed and broken, the rogue bull just a bit windward of the rest. Cattle would have been hunkered in the cattail coulee just below the hill, but not these weatherproof beasts. Gordy stopped the pickup, passed me the binoculars, and it was like looking back 150 years, nothing but snow-crusted, wind-blown grass and the mighty murderous bull, four inches of ice along his back and his breath like smoke in the sub-zero cold.

We circled ’round the pasture, a mile or so downwind, parked the truck and picked our way along the brushy cover of the coulee.

A Turnbull Marlin 1895 in 45-70 Gov’t.

I carried an 1895 Marlin lever gun, caliber 45-70 Government. Originally introduced in the year of its name, it was in production ’till the Great War suspended manufacture of civilian arms in 1917. It took Marlin another half century to get around to making more, and mine was one of the first newer rifles. It was a beauty: half-magazine, deeply blued with a hand-rubbed, oil-finished walnut stock.

Though the 1895 came too late for the great buffalo slaughter, the 45-70 was certainly widely employed. The old-time hunters took a stand and fired heavy bullets with long, looping trajectories at extreme ranges, sometimes killing a dozen or more before the rest of the herd became suspicious and moved off, often at walking speed. A critter genetically predisposed to do battle with wolves and grizzlies is not easily spooked, unless by each other, in such case they were known for some monumental stampedes.

But the Marlin sights were not infinitely adjustable. I must get close. I would crawl if I had to and I did.

But the Marlin sights were not infinitely adjustable. I must get close. I would crawl if I had to and I did.

No time to fart or fumble, on my belly with a beast that had tried to kill a man only the day before.

The ammo was Remington half-jacketed soft points, 405 grains, old enough to bear the advisory “For Marlin and Winchester repeating rifles and Colt machine guns.” That would be the Gatling Gun, nine rotating barrels driven by a hand-crank. The cartridges were old but still shiny bright. I had already burned up half the box with no misfires.

At 80 yards, I rose to my feet and took my shot offhand. The bullet struck with a noise like a baseball hitting a feather pillow, raising a great cloud of dirt and hair and snow.

The bull took off at a dead run. About the time he first stumbled, the other bulls, maddened by the blood-smell, hit him simultaneously. Another cloud of hair and snow, and they dribbled his carcass like a basketball, you never seen such.

Gordy was behind me, toting a single-action 44.

“Great God, man, what now?” I howled.

“Shut up,” he whispered, “and don’t move. They might think we’re a tree.”

“Gordy, there ain’t a tree for miles.”

“Shut up.”

I did.

Willard broke open a fifth of Christian Brothers Five Star, the favored local anti-freeze, and we commenced a powwow that burned up the rest of the morning. I offered to split the carcass with Willard, but Gordy wanted his share. So Willard took his half, and Gordy and I split the other. I took the front quarter, 300 pounds of grass-fed good eating.

Then there was the matter of the head and hide. Willard took the skull. He would boil it clean and nail it to his gatepost, once the ground thawed enough to replace it. I sent the hide off to the tannery and threw the robe atop my double bed. It hit the floor on both sides.

Lonesome cowboys used to sing a song around their campfires: “Buffalo gals won’t you come out tonight and we’ll dance by the light of the moon.” And indeed, they did, and that robe saw some serious moonlight dancing.

Buffalo dreams.

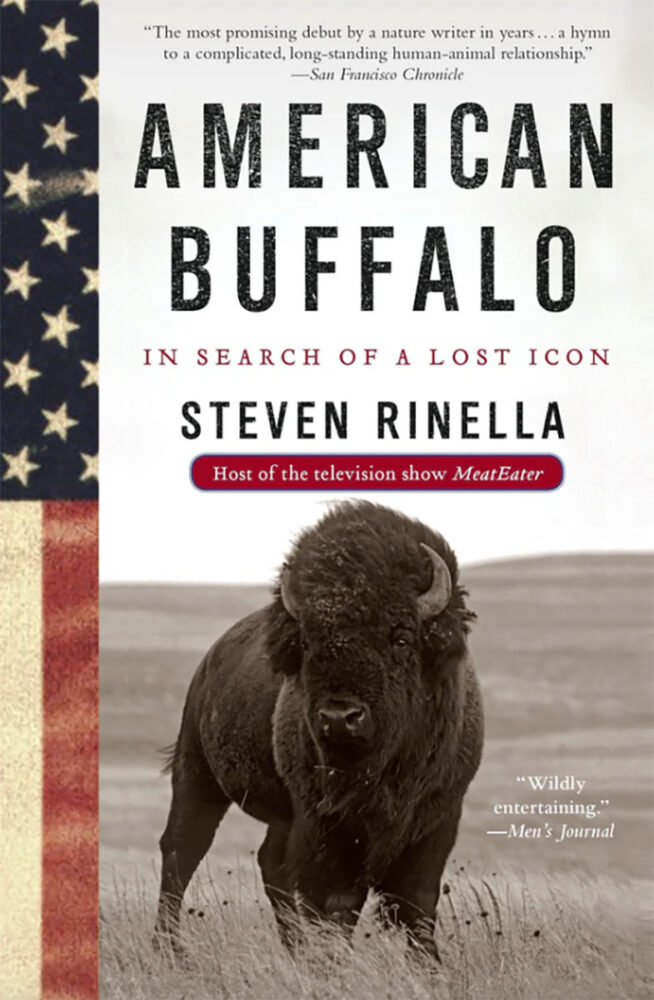

A hunt for the American buffalo—an adventurous, fascinating examination of an animal that has haunted the American imagination. Buy Now

A hunt for the American buffalo—an adventurous, fascinating examination of an animal that has haunted the American imagination. Buy Now