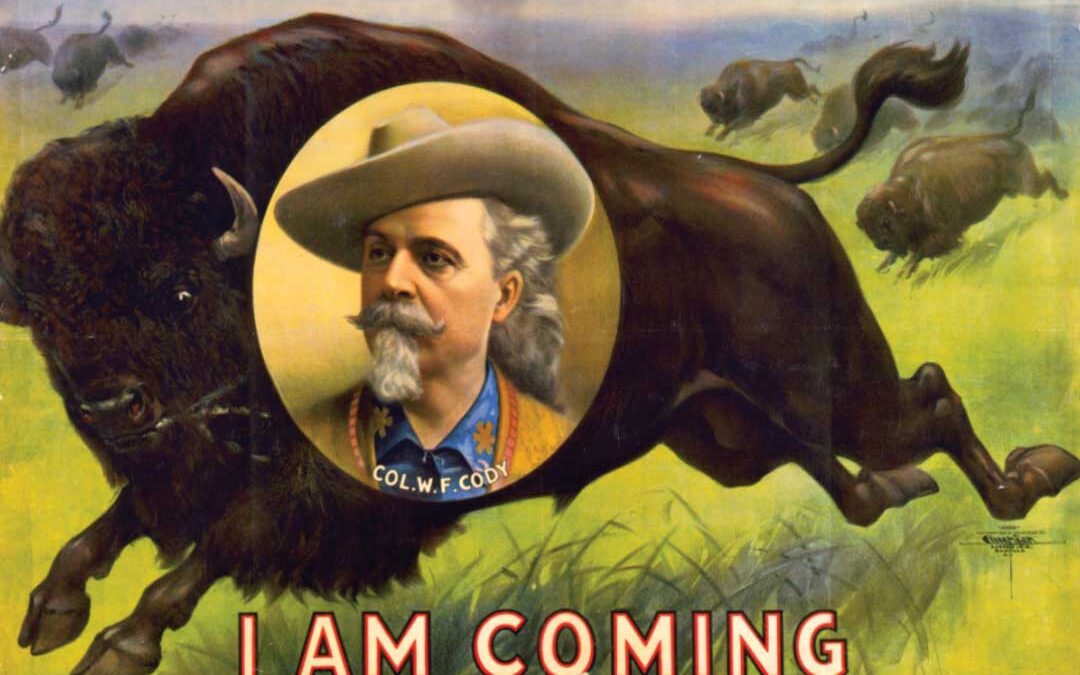

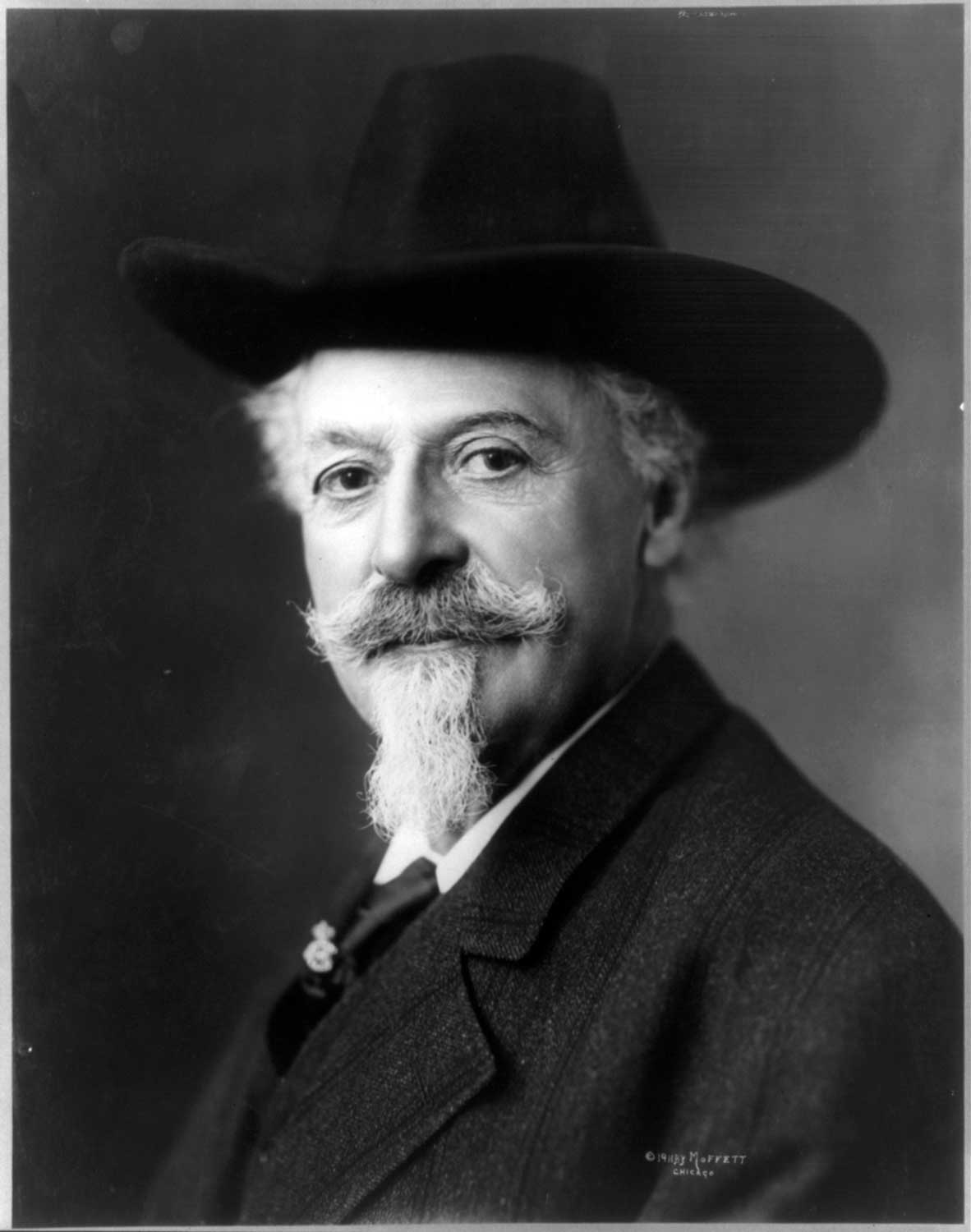

No individual so personified the American West and spirit of the late 1800s as William Frederick “Buffalo Bill” Cody. Pony Express rider, scout and legendary hunter, Buffalo Bill and his popular Wild West show toured the U.S. and Europe for more than 30 years.

Cody earned his nickname after slaying 4,250 buffalo in one year to provide meat for laborers on the Kansas Pacific Railroad. Most of the animals fell to his .50 caliber trap-door Army issue Springfield, which he named Lucretia Borgia after seeing Victor Hugo’s play about the alleged murderess.

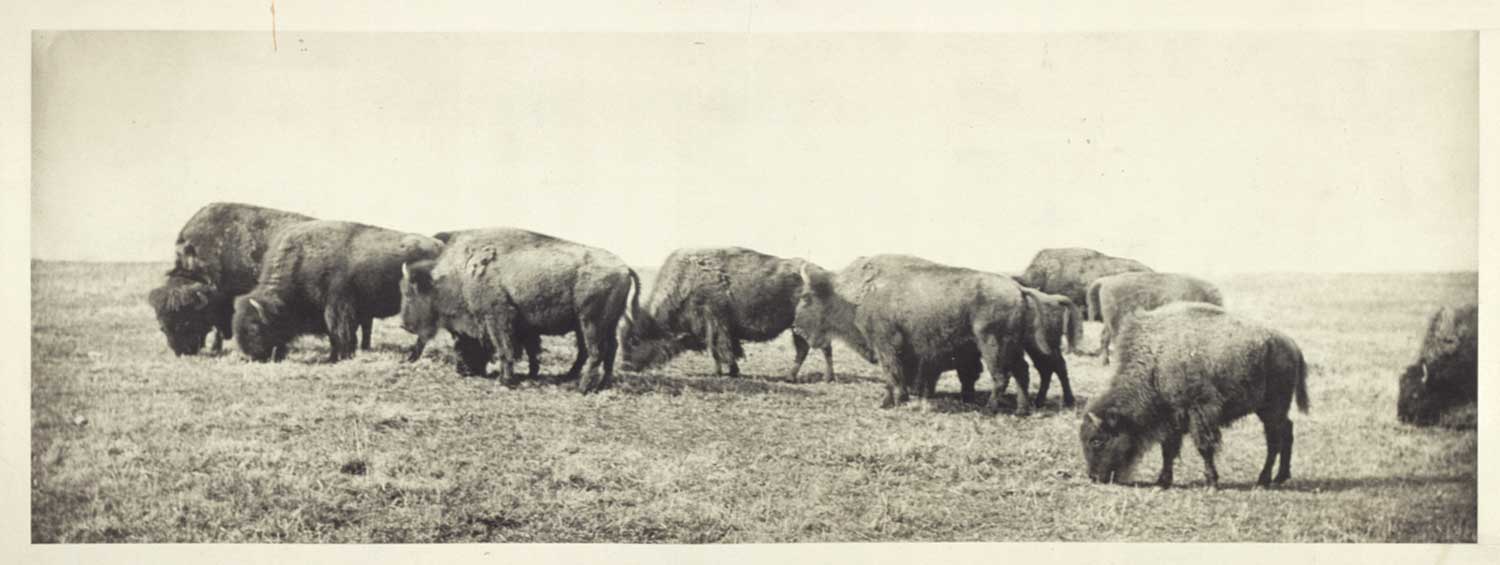

Though an ardent investor in schemes to develop the West – he and other investors planned a city the size of St. Louis on the Shoshone River and once hatched a deal to acquire 3.5 million acres on the north rim of the Grand Canyon – Cody became increasingly concerned with conservation. Campaigning for Theodore Roosevelt, he championed the preservation of land and wildlife. Later on, he used his own TE Ranch to breed buffalo in a successful effort to help protect them from extinction.

Highly respected not only for his skills as guide and hunter, Cody was a man of integrity and easy manner who won lifelong friendships with powerful Civil War generals, among them Philip Sheridan, who convinced his friends in high places that Cody was a fabulous guide.

In the following article abridged from an 1894 issue of The Cosmopolitan, we’ll join Buffalo Bill on five of his grandest hunts. –John Ross

The first great hunter who came to this country in search of big game of whom I have knowledge was Sir George Gore. I was a boy at Fort Leavenworth in 1853 when he arrived there from London and fitted out his own expedition. At that time buffalo, elk, deer and antelope were so numerous upon the plains, and all through the Rocky mountain region, that we frontiersmen were somewhat naturally surprised to find that an English gentleman would come all the way across the ocean, and make the tedious journey from the seaboard to the frontier, with no other end in view than the chase.

The ready good fellowship, however, with which Sir George Gore adapted himself to his surroundings, soon made him a favorite. His party was made up of about 200 men, the trappers and guides being engaged at Laramie 700 miles west of Leavenworth. He had no companions to share the expense of his extensive equipment, and no guests to join him around the campfire in the evening. He went in for genuine sport, and bade goodbye to civilization when he left St. Louis. At that time there was no railroad west of Chicago, which is 1,500 miles east of Laramie, and Sir George took the river route up from St. Louis.

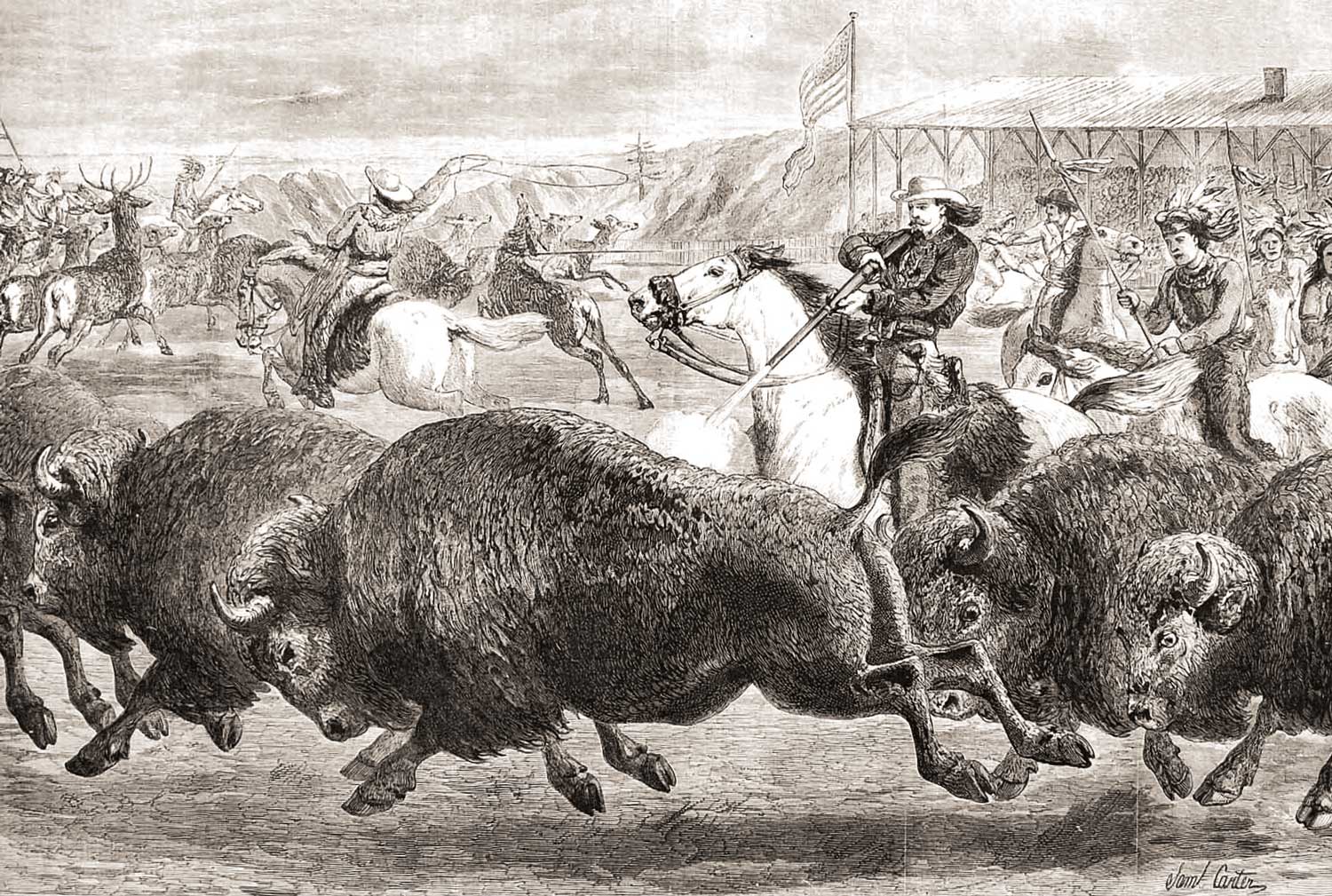

In his Wild West shows at the Great American Exhibitions, Wild Bill and his mounted cowboy and Indian actors chased and shot live buffalo and elk.

From Laramie, Sir George Gore’s little caravan went out into the Big Horn Mountains, into the thick of game country. There, after bagging as much as his heart could wish, his camp was surprised one evening by the Indians. The redskins ran off all his horses, traps and trophies, and there was nothing left for him and his men but to foot it, 150 miles, back to Laramie, leaving some of their companions dead on the field of battle.

The slaughter of seven of Sir George Gore’s men by the Indians, 40 years ago, was an incident which might have attained international importance had there been any possible way for the United States government to accept the proposition that his rage at the redmen led him to make with great promptness. He actually proposed to Uncle Sam to whip the entire Sioux nation at his own expense, and vowed that he could, in 30 days, equip a little army of his own which would wipe those murderous thieves off the face of the earth. Naturally enough, Sir George’s proposal could not be accepted, and the next year saw him hunting down in Florida where he led a large party of sportsmen and a big pack of hounds.

Sir John Watts Garland was another great English huntsman. He came over here about 1869. At different points on the plains and in the mountains he established camps and built cabins, to which he would return regularly about once every two years. In his absence, his horses and dogs were left at these camps, in the charge of men employed for that purpose. It was John Watts Garland, it seemed to me, who first realized the value of the trained horse for hunting the buffalo. As a matter of fact, whatever his speed and bottom, a horse must be broken in to that special task to enable him to give his rider the best service when once in sight of a herd. Big-boned Indian ponies, or, as we call them, frontier horses, generally made the best mounts for this purpose. I have seen Garland offer as much as $1,000 (about $16,000 today) for one that had a reputation and took his fancy….

I met him two years ago (1892) in London, and we lamented the disappearance of big game from the United States, acquiescing, however, in the undoubted fact that it has practically ceased to exist. In these days, when the elk and buffalo are traditions, it is difficult, perhaps, for sportsmen to realize the wild exhilaration attending their pursuit on horseback. Elk were hunted much the same way as buffalo, the perfection of the sport being found in the saddle.

Sir John Watts soon discarded the English saddle that he brought over with him, and the truly British custom of declining to drink anything until after dinner, when all the day’s work had been finished. No great time was required for him to learn that a cocktail before breakfast was considered entirely the thing on the prairie, and that anything else than a California saddle was out of place.

His democratic ways made him very popular with the plainsmen. When he went out with a party, he roughed it like the rest of us, slept in the open on his blanket, took his turn at camp duty, and rode his own horse in the races we got up for our amusement. He discovered speedily that the English thoroughbred was by no means so well fitted for frontier use as the coarser western horse, which was more accustomed to avoiding prairie dog holes and better understood the lay of the land.

The destruction of the big game in the West, about which so much has been written, and which has been ascribed to so many causes, is simply a natural consequence of the advance of civilization. There is no longer any frontier. People live everywhere, all over the Rocky mountain region.

I may mention one of two interesting facts which illustrate this metamorphosis, and which seem to me to have hitherto escaped record. Not only has the buffalo-grass, which once grew all over the country, disappeared entirely, and given place, naturally, to the blue-joint grass which is now found there in profusion, but market atmospheric conditions have been in the same way entirely changed….

I have never seen this strange fact about the dew recorded anywhere. In the old days it was possible to walk anywhere in that country, in the grass or out of it, at any time of the day or night, without wetting one’s moccasins. There never was dew on any of the Great Plains between the Missouri River and the Rocky mountains. You slept out in your blanket at any season of the year, and when you awoke in the morning it was as dry as when you lay down. There has been an absolute change in all of this. Heavy dews fall with as much regularity there as elsewhere.

I have a theory of my own to account for this phenomenon, and that is that the erection of wire fences, which has unquestionably greatly increased the downfall of rain, has in the same way, by the attraction of electrical currents, brought about the dew.

The third of the great hunters whom I have known was Lord Adair, who is now Earl of Dunraven, owner of the famous Valkyrie. He came with Dr. Kingsley, a brother of Charles Kingsley, the well-known author, and arrived at Fort McPherson in 1869. This fort is on the Platte River about 18 miles from the town of North Platte where my ranch is. Lord Adair brought with him a letter of introduction from General Sheridan. He was a pleasant young fellow and I enjoyed hunting with him. We camped along the Loup and Dismal rivers, and went off for elk, for the most part on horseback.

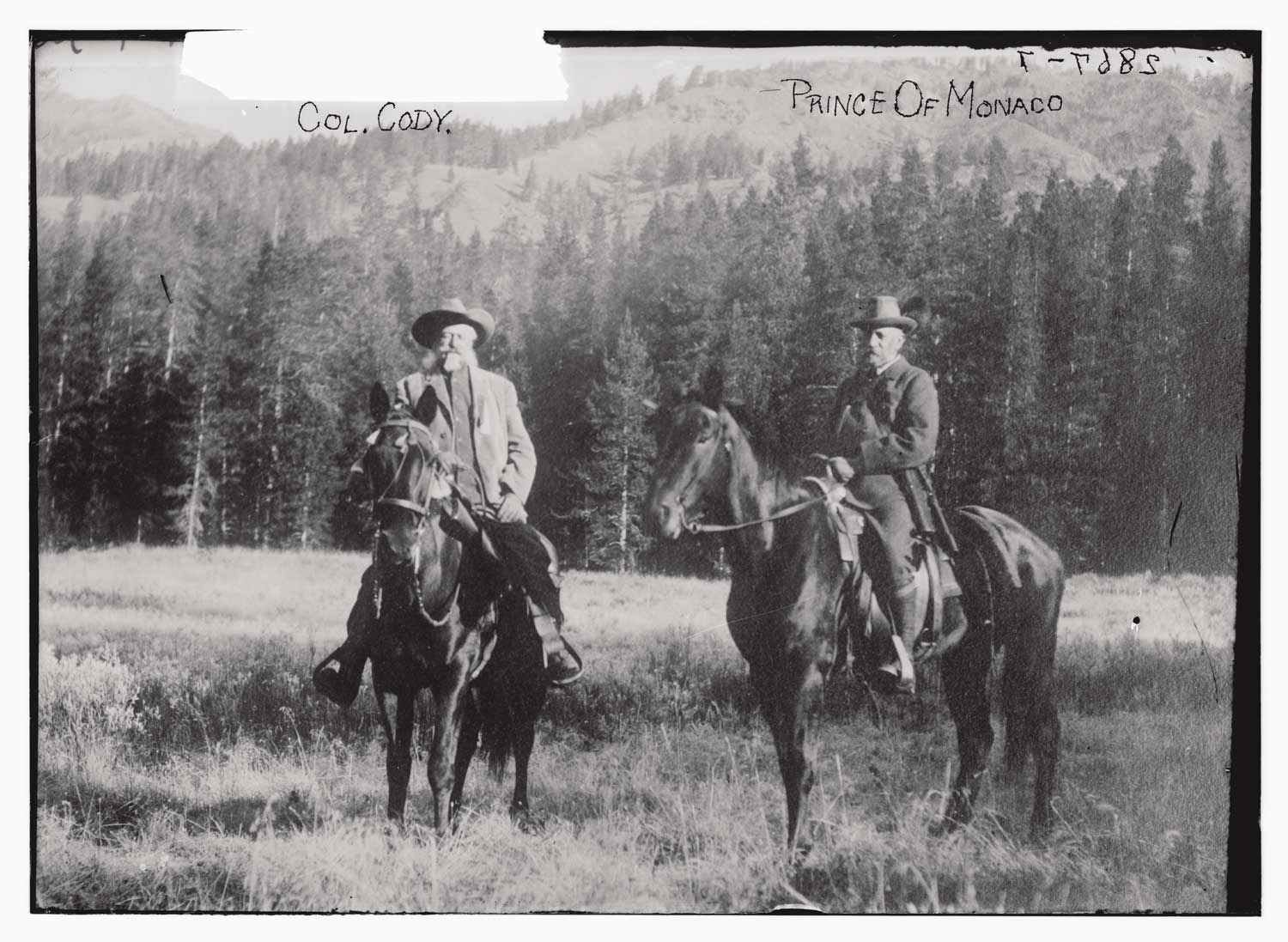

Colonel Cody poses with Albert I, prince of Monaco, during their 1913 hunting trip near Cody, Wyoming.

The elk hunt of those days was managed in about this way: six or seven of us would start at sunrise on our prairie horses and get as close as possible to the elk, which would be feeding in the open, 200 or 300, perhaps, in a bunch. Those long-legged beasts were swifter than the buffalo, and they would let us get within a half-mile of them before they would give a mighty snort and dash away after their leader. Then came the test of speed and endurance. They led the horses on a wild race, and it put our chargers to their mettle to overtake the game.

Right in among them we would spur, and dropping the reins use the repeating rifle with both hands. The breech-loading Springfield piece of .50 caliber, the same as used in the regular army, was our favorite rifle at that time. Only the master of the hunt, or his guests, or companions, would do any shooting: the hunters and attendants would occupy themselves in lassoing young elk and taking them back to the camp alive. Lord Adair shipped a good many of those captured to his place across the water.

Among the interesting things that the United States Army had been, at one time or another, called upon to do is acting as an escort to distinguished hunting parties. There was always a military escort for Lord Adair, and a lot of Army wagons went along to take the game back to the fort, where it could be used. He was much opposed to wanton waste. Our first expedition into the mountains, for bear, would take us as far away as Fort Steele, 600 miles west of Fort McPherson, and we would be gone four or five weeks. Lord Adair was the first of these visiting sportsmen that I remember to have had a military escort. Garland and Gore provided their own.

Editor’s Note: After Lord Adair, Cody guided a party of lavish New Yorkers. Nothing, however, would trump the expedition of Russia’s Grand-Duke Alexis.

Soon after the departure of the New Yorkers to their home, I began preparing to receive Grand-Duke Alexis. I had to keep a lookout for the game, and arranged with Spotted Tail, the great Sioux chief, to bring 100 of his braves to show Alexis how Indians hunt buffalo. The Russian Party reached North Platte (in January, 1873) by the Union Pacific railroad, in a special train. This was something extraordinarily important and considered very complete for that time. The train was in charge of Mr. Frank Thompson who is now vice-president of the Pennsylvania railroad company. Camp Alexis had already been established and was in readiness, in a sheltered nook on Red Willow creek, in buffalo country 60 miles from Fort McPherson. There were hospital tents and wall tents for officers and their guests, many of them floored and carpeted, and heated with stoves. Special pains were taken to make the dining room tents complete in every way.

The military escort consisted of two companies of cavalry and two of infantry, and the regimental band of the Second Cavalry. Generals Sheridan, Palmer, Tony and Sandy Forsythe and Ord, and General George A. Custer, Colonel M.V. Sheridan and Major Egan, of the Second cavalry, were in the party. Dr. Ash, who was General Sheridan’s surgeon general, was surgeon to the party. With soldiers, teamsters and cooks, there were probably 500 in all.

The Grand Duke was very successful. He killed eight buffalo. The ground was very slippery, it being in the dead of winter, and the game would purposely run over the roughest country in order to break up the horses, so he had good reason to be proud of his record. He rode Buckskin and shot the buffalo from his back.

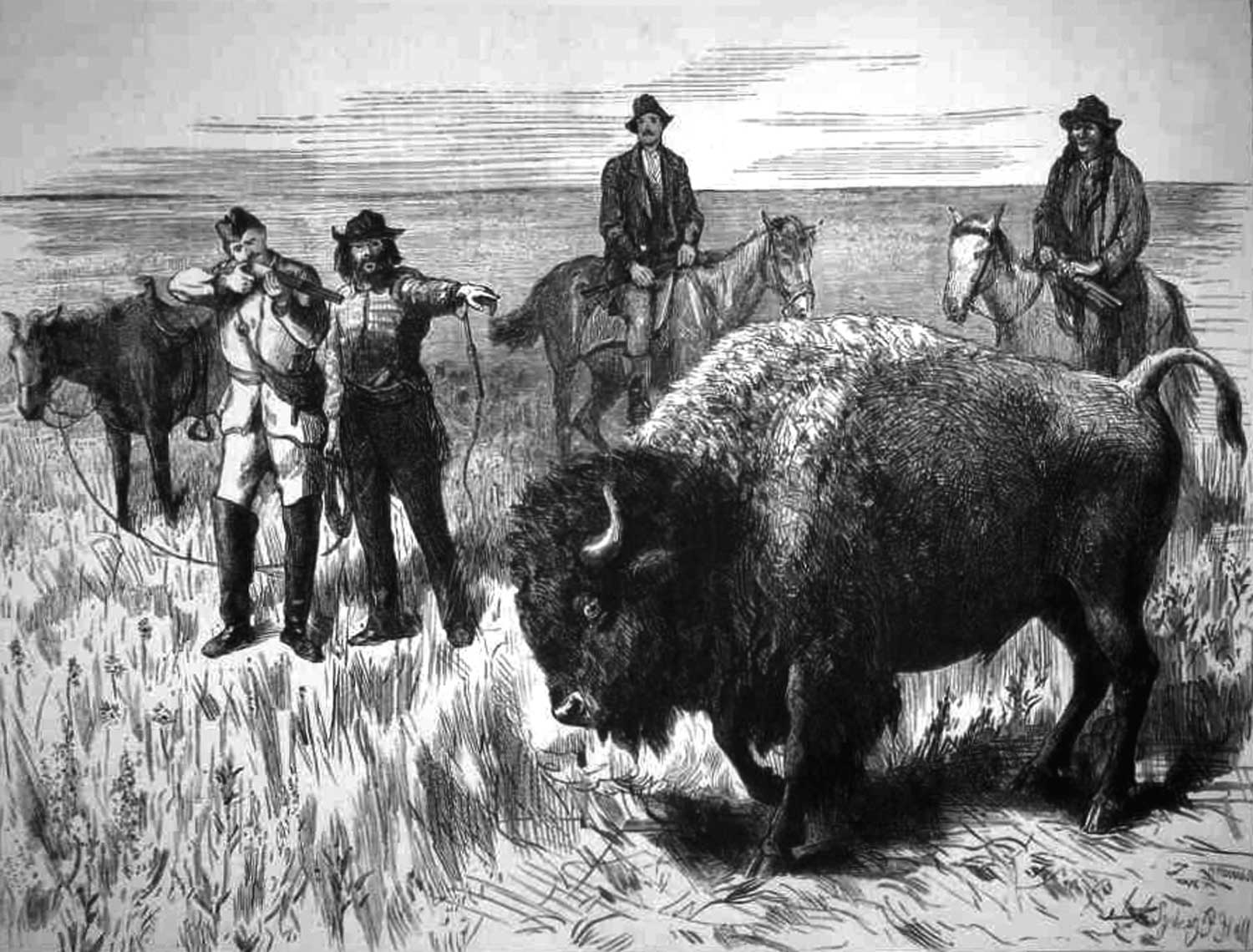

One afternoon was devoted to showing the Grand Duke the spectacle of an Indian buffalo hunt. The redmen made a “surround” as it is called, and then scattered and charged the herd, each picking out his own buffalo. They used bows, arrows and lances. We saw one of the chiefs, with a powerful hickory bow, about four and a half feet long, send a steel-pointed arrow entirely through one of the buffalo, while racing along by its side at full speed. The arrow was preserved by the Grand Duke as a trophy.

Another very interesting sight was an Indian on horseback, armed only with his lance, singling out a gigantic bison and thrusting his spearhead, while both raced at full speed, into the creature’s heart. These spears were about ten feet long, the steel head about a foot long, and the shaft about three inches in diameter. Considerable skill was necessary to apply the momentum of the horse just the right way to send the stroke home, it being necessary for the hunter to instantly let go the lance or be pulled from his steed. During the five days we were in Alexis’ camp, several hundred buffalo were killed.

The next and last great hunt in which I had a share was given by General Nelson A. Miles, who now commands the department of the Missouri, which used to be General Sheridan’s. Immediately after the close of the World’s Fair (United States Centennial Exhibition, Philadelphia, November, 1876), he sent me word that he wanted me to go as his guest. As this was the only time I had ever been a guest on a hunt, I accepted with great pleasure. I had my own tent and military orderlies to come at my beck and call, and I soon got to imagine that I was Sir George Gore and the Grand Duke Alexis all rolled into one. I don’t believe I would have accepted a ripe peach on a 20-foot pole.

The next and last great hunt in which I had a share was given by General Nelson A. Miles, who now commands the department of the Missouri, which used to be General Sheridan’s. Immediately after the close of the World’s Fair (United States Centennial Exhibition, Philadelphia, November, 1876), he sent me word that he wanted me to go as his guest. As this was the only time I had ever been a guest on a hunt, I accepted with great pleasure. I had my own tent and military orderlies to come at my beck and call, and I soon got to imagine that I was Sir George Gore and the Grand Duke Alexis all rolled into one. I don’t believe I would have accepted a ripe peach on a 20-foot pole.

We started at Fort Supply, I.T. (Indian Territory east of present-day Fort Supply, Oklahoma), and hunted down the Canadian River to Fort Reno, and over to the Washita River and into the Wichitah (sic) Mountains. We were gone about three weeks. General Miles had his military escorts establish in advance for us, and he combined duty and pleasure by inspecting different military posts as he passed through the country and holding councils with different tribes of Indians. It was sadly evident that there was no more big game to be had. The buffalo, elk, and antelope had long since disappeared. We only killed turkey, geese, chickens and deer.

NOTE: Buffalo Bill Historical Center is redesigning its Buffalo Bill Museum to present a more complete picture of William F. Cody as a “Man of the West, Man of the World.” The museum features interactive exhibits enabling visitors to accompany Buffalo Bill on some of his exploits and to attend portions of his Wild West show. Call (307) 587-4771 or visit www.bbhc.org.