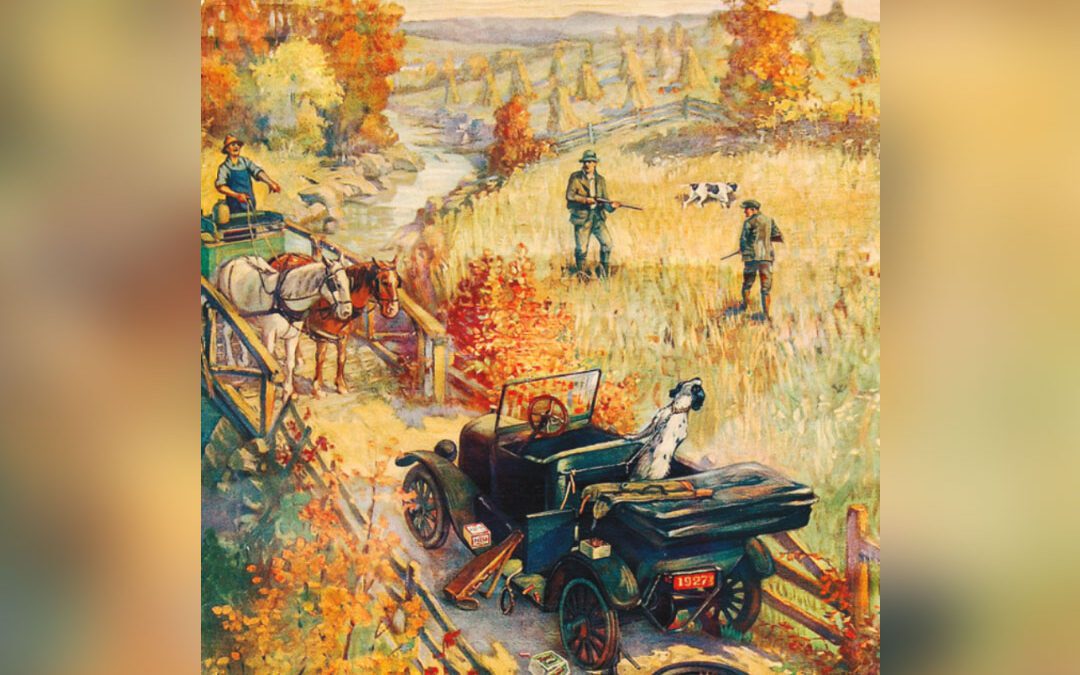

The Tin Liz sighed, sank on her haunches, sighed again and expired. The Old Man got out and looked at her innards suspiciously, crouched down to peer at her lower parts, thumped her a couple of times, like you’d tap a melon to see if it was ripe, and then shrugged his shoulders. He had the yellow, red-headed kitchen match shoved into his pipe before he spoke. He got the pipe going and poked the stem at the rusty old car.

“Clearly a case of death due to old age,” he said. “Far as I can figure, she’s burnt her bearings, the piston rings are gone, the spring’s bested, the gas pump is clogged, the brake linings are burnt out, the axle’s sprung, the electric system’s finished, and I think somebody forgot to put the crank in. We might as well shoot her, like a foundered horse. We are plumb forgot and five miles from home. What do you suggest?”

“I guess we better pick up the guns and leash the dogs and go back,” I said. “We can maybe hitch a ride, and then we can go to Gus McNeill’s filling station and get him to send somebody out to pick her up and tow her in.”

The Old Man snarled slightly, the wind riffling his mustache. He gazed at nothing in particular.

“Now there is my brave pioneer lad, my young Dan’l Boone, the Kit Carson of tomorrow.” His voiced lifted in a sissified tone. “We can maybe hitch a ride, and then we can go to Gus McNeill’s filling station and get him to send somebody out to pick her up and tow her in.”

The Old Man spat. “And this is the one that’s going to shoot lions and elephants. What do you think the dogs will think of us if we hitchhike our way back to a filling station” – he sarcastically accented the words – “if we don’t give the dogs something to do to earn their keep.”

“Well, sir,” I said, “it’s a good six or eight miles to where we were headed. You going to walk all that way and then hunt all day, and then walk thirteen miles home?”

“I don’t see why not,” the Old Man said cheerfully. “Old and ugly and sick as I am, I recon I can keep pace with any product of the machine age whose legs are so atrophied he needs transportation to go to the store for a box of gingersnaps. And who ever said we had to hunt thataway?”

“Well, there’s no birds around here,” I said. “Look at it. Broom grass. Scrubby oak. Cut-down pine. Sparkleberry bushes. Gallberry bushes. Some chinquapin. And right on the highway. Nobody hunts here. It’s been shot out.”

Himself snorted. “Shot out, is it now? And why would it be shot out, me darlin’ lad?” The Irish used to come out of him when he was treading heavy on the sarcasm. “Me gay brothy boy, tell why it’d be shot out, as so ye say.”

“Too close to town. Too easy to get at. Too many cars stopping along to let the dogs loose and burn down the coveys. Too many turpentine camps and brush fires.”

“That’s better than I thought you’d do,” the Old Man said. “You’re right in all you say except in just one thing – the land has had a rest, and the birds have had a rest with it. There’s no land on the face of the earth that doesn’t need a rest, whether you’re growing crops or birds or animals.

“The automobile is the curse of civilization, especially for the wildlife that lives by the side of the road, because any idiot can park his car by a field and, like you say, turn loose the dogs and slaughter a covey and be off with himself before the farmer that owns the fringes finds he’s shot a cow and two suckling pigs as well. The hit-and-run hunter doesn’t care about conserving the stuff for next year and for all the next years.”

The Old Man spat. “If one of these car-without-permission hunters found a covey running down a corn row, he’d shoot it all on the ground, and probably sell the birds to boot.”

I didn’t say anything. I went and let the dogs loose to life their legs, got the guns in their cases, the thermos bottle and prepared to march.

The Old Man started off again. “When you had to walk five miles or drive in a buggy for half a day to get where you were going before you could hunt, appreciated what you were hunting, and took some care of it – which,” he emphasized, “had something to do with assuring the farmer you wouldn’t kill his best brood sow the first time she came at you out of a cornfield. You kind of watched out for your cigarette butt and matches, and tried not to burn his hayfields down, and you might also stop off at the house and give him a couple brace of birds. In return for which he might tell you where he had some turkeys more or less baited, and ask you to spend the night so’s you could shoot one the next morning. But the automobile has ruined it. You can go a hundred miles in three hours, and shoot half the way along.”

The Old Man glanced at the stricken car. “Look at that hunk of tin tragedy,” he said. “We are marooned as much as if we had just been cast ashore on a desert island. Henry Ford made it. All the knowledge of mankind is in it, and look at it. As useless as a busted buggy with a dead mule in the shafts.”

We started to walk down the road, heading home. The dogs had been circling, quartering and stopping as dogs will to carve their personal initials on the likelier-looking bushes. All of a sudden I saw a patch of white where the liver-and-white setter, Sandy, had headed into bush. It refused to move, this white patch.

I said to the Old Man, “Either Sandy’s froze stiff, or he’s found a covey of birds. Look yonder.”

The Old Man snorted again. “Couldn’t be birds. This place is shot out. I got it on the best authority. Probably nothing but field larks. Sandy had a hot nose when I turned him loose this morning. Better unlimber the guns, though. Probably a rattler or a horse terrapin. Couldn’t be any birds along here. Too public. Where’s the shell bag?”

I was in a fever when I opened the cowhide cases and started to fit the guns. Maybe you remember, the Old Man had a real peculiarity about guns. He wouldn’t use one of those cases that took a whole gun. He said a broken gun never killed anybody, and he wouldn’t ride in a car with a gun that was all in one piece. While I was fumbling the guns together – and you can get the Old Man wasn’t helping me any – I kept one eye on that patch of white showing through the dark green of the gallberries, and it never looked like moving.

With shaky fingers I handed the Old Man a fitted-together shotgun and half a box of shells, and dropped the other half into my canvas hunting coat. We loaded as we walked up to the patch of white, and there was old Sandy, as stark as a statue, and old Frank, looking like a twin to a burnt stump, just behind him.

“I don’t think this would be larks,” the Old Man murmured. “Or a rattlesnake. Or a terrapin. Let’s us go see.”

We walked up to the dogs, walked past, scuffed the twisted low-broom, and what amounted to two million birds got up. I fired into the middle of the two million and saw nothing fall. The Old Man unleashed his ancient weapon, too, although I never heard it. I looked at him and he looked at me. I shrugged my shoulders and he shrugged his.

“Must have been snakes,” he said. “But have you got any idea where the single snakes went?”

“They looked like they were going down either into that patch of broom or off into those little scrubby oaks,” I said. “How many birds would you say were in that covey?”

“Less than a hundred thousand,” the Old Man replied, putting fresh shells in his gun. “Twenty-five at least. Looked like old birds, too. Let’s go see if the dogs can smell singles.”

We went to where the singles seemed to have lit, and they stuck fast as glue. It was one of the few times we ever overshot a quota, but it seemed in the Old Man’s logic that a covey of 25 or 30 birds could spare eight, and eight was what we shot.

“Just like,” the Old Man said sternly, popping the proceeds of a neat double into his coat, “all the other roadside hunters. Game hogs.”

We walked along the road and waved the dogs from one side to the other. In something less than five miles to the city limits, the dogs found five coveys, one of which was bivouacked in the front yard of a suburban friend. We did not shoot that covey, since it involved firing through the windows of the living room.

But we shot sufficient birds to have a heavy-hanging hunting coat by the time we approached the general vicinity of Gus McNeill’s filling station. I would like to tamper with the truth a little and say we filled our limit just abaft the gas pumps, but I cannot tell a lie. There were no birds in the vicinity, only Gus and a few shiftless friends.

“Where you-all been?” Gus asked as we trudged down the road, the dogs leashed again, both of us carrying a sheathed gun.

“Huntin’, the Old Man said dryly.

“Huntin’ what?” Gus asked.

“Birds.”

“Get any?”

“Some.”

“Where’s your car?”

“Back yonder apiece.”

“How far?”

“About five mile.”

“How many birds?”

“Twenty, more or less.”

“The car broke down?”

“Yep. Can you send somebody to tow her home?”

“Sure. Where’d you get the birds? They’ve been kinda scarce lately.”

“Oh, we hunted up ’way ahead of the car. I got a couple of farms the folks let me use from time to time. You know the way it is.”

The Old Man slipped me a wink. Gus was a shotgun man, too.

“You want to use the car tonight, or will tomorrow be okay?” Gus inquired.

“Tomorrow’ll do,” the Old Man said. “But we would appreciate it if you’d give us a lift home now. My feet are killing me from pounding all this asphalt. Seems to me walking was easier when we had clay roads. At least they fit my feet better.”

We drove home and Gus let us out. I took the dogs to pen and came back to take the guns off the front porch to clean them, and then went back to where the Old Man had a rather massive pile of quail on the back steps.

“Some farms that folks let me use. Do not tell a lie,” I said reprovingly. “Never tell a lie.

It says so in Sunday School.”

The Old Man was counting the little beautiful bobwhites. “Twenty-two,” he announced happily. “All out of a shot-out area. Now, what did I tell you about the curse of the machine age? If that Liz had held together, we would of run right past the birds, and probably come home with nothing. The auto is the curse of the hunting man. And just think all we had to do was walk down a road.”

“Do not tell a lie, like Miss Lottie says,” I said sternly, for me.

“Miss Lottie be blowed,” the Old Man said, still happy. “She never knew anything about quail hunting or game conservation. We are game conservationists, protecting the national resources from tourists. We are protecting them for ourselves, which is conservation of a sort, even if it’s selfish.”

“I suppose I’d better start cleaning them, like always,” I said.

“Tonight, I’ll help you,” the Old Man said, and I’d like to have dropped dead from shock.

-Yr. Ob’t Sv’t Bob Ruark

© 1954 by Robert Ruark, renewed 1982 by the estate of Robert Ruark. Permission to reprint granted by Harold Matson Co., Inc.