It seems as if Fate had chosen my hunting companion, Arthur Young, to add to the honor and the legends of the bow. At any rate, it fell to his lot to make two trips to Alaska between the years 1922 and 1925.

He and his friend Jack Robertson were financed in a project to collect moving-picture scenes of the Northland. They were instructed to show the country in all its seasonal phases, to depict the rivers, forests, glaciers, and mountains, particularly to record the summer beauties of Alaska. The animal life was to be featured in full—fish, birds, small game, caribou, mountain sheep, moose, and bear, all were to be captured on the celluloid film, and with all this a certain amount of hunting with the bow was to be included and the whole woven into a little story of adventure.

Equipped with cameras, camp outfit, and archery tackle, they sailed for Seward. From here they ventured into the wilderness as circumstances directed. Sometimes they went by boat to Kodiak Island, sometimes to the Kenai Peninsula, or they journeyed by dog sleds and packs inland. They spent the better part of two years in this hard, exacting work, often carrying as much as a hundred pounds on their backs for many miles.

Great credit must be given to Robertson for his energy, bravery, and fortitude. His work with the camera will make history, but for the time being we shall focus our attention on the man with the bow. Only a small portion of Young’s time was devoted to hunting; the exigencies incidental to travel and gathering animal pictures were such that archery was of secondary importance.

He hunted and shot ptarmigan, some on the wing; he added grouse and rabbit meat to the scant larder of their “go-light” outfit. He also shot graylings and salmon in the streams.

He could easily have killed caribou, because they operated close to vast herds of these foolish beasts. However, at the time it seemed that there was no hurry about the matter—they had meat in camp, and pictures were of greater interest just then. They expected to see plenty of these animals.

Strangely enough, the herd suddenly left the country, and no further opportunity presented itself for shooting them. This was no great disappointment because the sport was too easy.

What did seem worthwhile was the killing of the great Alaskan moose. These beasts are the largest game animal on this continent, with the exception of the almost extinct bison.

Young had his first chance at moose while on the Kenai Peninsula. Here the boys were camped, and having finished his camera work, Art took a day off to hunt.

In the afternoon he discovered a large old bull lying down in a burnt-over area where approach by stealth was possible, so he began his stalk with utmost caution, paying particular attention to scent and sound. By crawling on his hands and knees he came within a 150 yards, when his progress was stopped by a fallen tree. To go around it would expose him to vision; to climb over would alarm the animal by snapping twigs; so Young decided to dig under.

He worked with his hunting knife and hands for one hour to accomplish this operation. When he had passed this obstacle, he continued his crawling till he reached a distance of 60 yards. At this stage, Art called the old bull with a birch bark horn, then the moose heard him and stood up.

The brush was so thick that he could not shoot immediately, but waited as the old bull circled to catch his wind and answered the challenge. When he presented a fair target at 70 yards or so, Art drove an arrow at him. It struck deep in the flank, up to the feather ranging forward.

The bull was only startled a trifle and trotted off a hundred yards. Here he stopped to look and listen. Young drew his bow again, and, overshooting his mark, his arrow struck one of the broad, thick palms of the antlers. The point pierced the two inches of bone and wedged tight, making a sharp report as it hit. This started the animal off at a fast trot.

Young followed slowly at some distance and soon had the satisfaction of seeing the moose waver in his course and lie down. After a reasonable wait the hunter advanced to his quarry and found him dead.

The triumph of such an episode is more or less mixed with misery. The pleasure undoubtedly would have been greater had some other lusty bowman been with him, but as it was, he had to feast his eyes alone. Moreover, he had to make his way back to camp, which was some eight miles off, and night was rapidly coming on.

This part of the story was just as thrilling to Art, because he must stumble through the rough land of “little sticks” in the dark with the constant apprehension of meeting some unwelcome Alaskan brown bear, which were thick there, and also the extremely unpleasant experience of running into dead trees, tripping over fallen limbs, and dropping into gullies.

He reached camp ultimately, I believe. Next day he returned with his companion for meat, his antler trophy, and a photograph. The bull weighed approximately 1,600 pounds and had a spread of 60 inches across its antlers.

Upon the second expedition a year later, Young bagged another moose. Here the arrow penetrated both sides of the chest and caused almost instant death, showing that size is not a hindrance to a quick exodus.

It is surprising, even to us, to see the extreme facility with which an arrow can interrupt the essential physiological processes of life and destroy it. We have come to the belief that no beast is too tough or too large to be slain by an arrow. With especially constructed heads sharpened to the utmost nicety, I have shot through a double thickness of elephant hide, two inches of cardboard, a bag of shaving, and gone into an inch of wood. We feel sure that, having penetrated the hide of a pachyderm, his ribs can easily be severed and the heart or pulmonary cavity entered. Any considerable incision of either of these vital areas must soon cause death. And this is a field experiment which we propose to try in the near future.

There is a legitimate excuse for shooting animals such as moose, where food is a problem and the bow bears an honorable part in the episode. We feel, moreover, that by using the bow on this large game we are playing ultimately for game preservation. By shaming the “mighty hunter” and his unfair methods in the use of powerful destructive agents, we feel that we help to develop better sporting ethics.

Editor’s note: An excerpt from Pope’s Hunting with the Bow and Arrow.

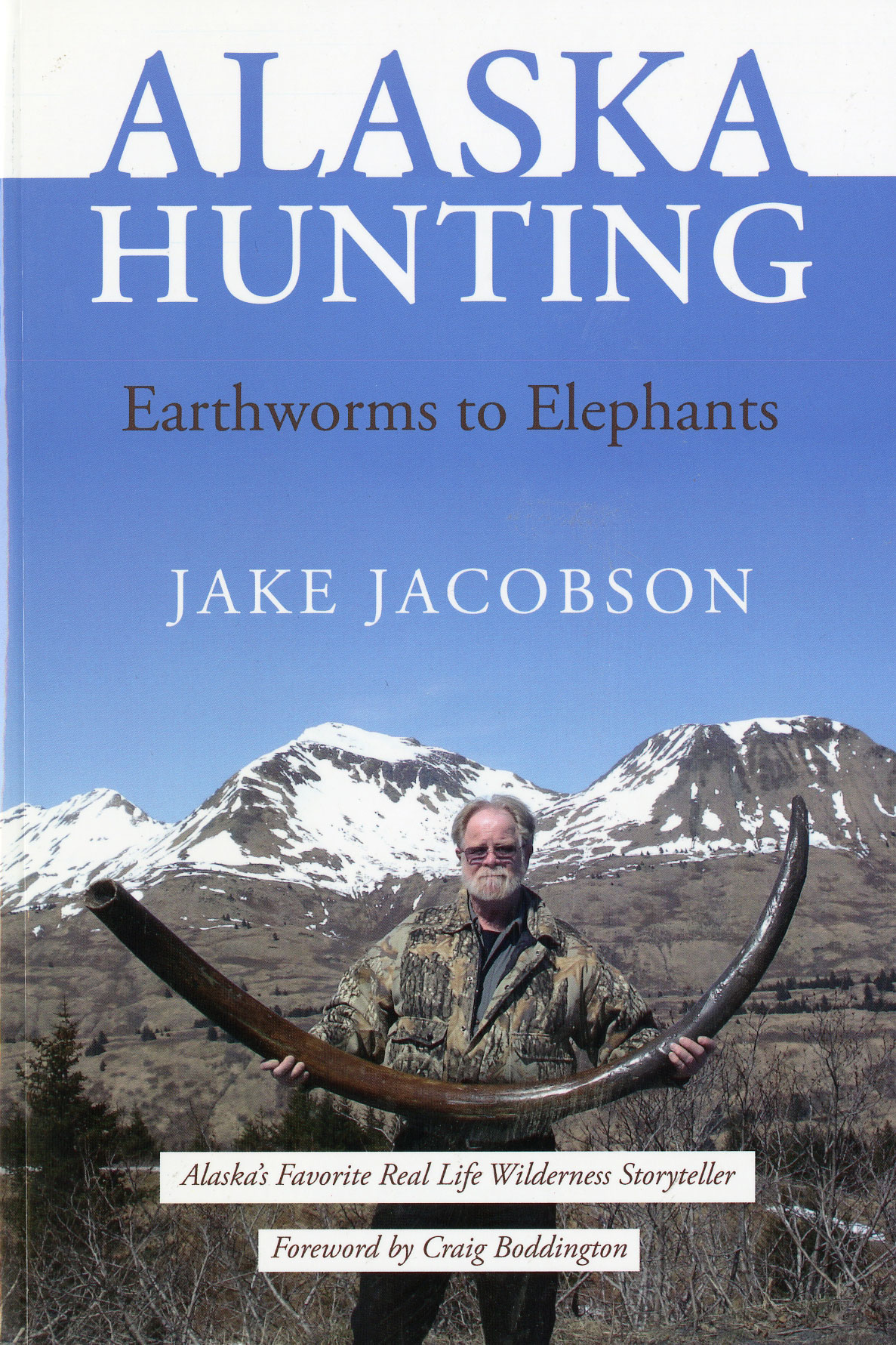

A collection of 39 stories, is intended to be seasoning for a Hunters’ pie, rural Alaska style. Most hunters extol the charismatic mega fauna, but pursuit of lesser game often takes center stage. Occasionally hunting discoveries lead to other endeavors, from jade mining to gold prospecting and fossil recovery. Possibilities are limitless. As we engage in hunting and fishing pursuits memories are laced with the big ones–the exceptional, genetically endowed giants–but some of the brightest memories are of average representatives of their species. What made them so memorable was the combination of circumstances under which they were taken–or lost. Companions, whether human or animal, often make the hunt memorable and its recollections of trophy quality. Buy Now

A collection of 39 stories, is intended to be seasoning for a Hunters’ pie, rural Alaska style. Most hunters extol the charismatic mega fauna, but pursuit of lesser game often takes center stage. Occasionally hunting discoveries lead to other endeavors, from jade mining to gold prospecting and fossil recovery. Possibilities are limitless. As we engage in hunting and fishing pursuits memories are laced with the big ones–the exceptional, genetically endowed giants–but some of the brightest memories are of average representatives of their species. What made them so memorable was the combination of circumstances under which they were taken–or lost. Companions, whether human or animal, often make the hunt memorable and its recollections of trophy quality. Buy Now