For any hunter, fancies flip and flop and morph. Change seems a common entity. As a bowhunter, my lifelong hunting journey was no exception.

A green vine, thumb-sized and flexible, served well for the bow – in those tender years of boyhood. A three-day life maximum for the bow before it took on pronounced string follow. But it sent projectiles downrange. Arrows of sassafras saplings whittled with a pocket knife and shot heavy-end forward. Unfletched. These and others of like kind were grand tools of allure, absorbing and infatuating. I was captivated.

Becoming a Bowhunter

Santa showed up Christmas of my 11th year with a bundle of delight. He picked it up at Sears. A real bow. Arrows, too. Life changed for the better that morning. A journey had begun, a passage that took me through decades and into these most recent and awkward episodes of old age. But the various bows never failed to inspire. They went with me to multiple states and Canadian provinces. Even to Africa. They, some of them, are still with me.

I suppose any hunter experiences periods of preference and experimentation and contemplation, along the way employing varied tactics and implementations and holding an equally varied list of philosophies while progressing or regressing or whatever may come. Fancies flip and flop and morph, at times in whimsical mayhem. Change seems a common entity. I as a bowhunter was no exception.

The author (right) and his PH make plans for a final stalk on a nyala.

The Recurve Bow vs. Longbow

Life as a bowhunter witnessed my courtship with alteration and amendment. I had my indiscretions. Five years’ worth, in fact. Wheels and cables afforded more range and speed but cowered at the mention of essence, tucked tail and ran when stared at by the telling eyes of je ne sais quoi. Romance rescued me. My heart belonged to simplicity. One brisk pre-dawn during those years of misdirection, I dropped my release aid from the treestand. I there recalled a sleek creation of Fred Bear hanging on a rack in my office, so I went home and apologized to my true love.

The Bear was a beauty. Slick and trim and streaked with green laminates. A recurve worthy of its namesake, registering 55 pounds at 28 inches. It, with XX75s was a thing of grace and efficacy. Those arrows slid away with nothing more than a faint hiss and landed where they should each time I released the string. That is if I did what I knew how to do. During that same season I dropped the release aid, that bow and those arrows accounted for a fat doe. She tipped from a wooded draw and into a corn field along which I was stationed.

So enamored of that bow I was that I determined to commission a custom rig. It was another unit of perfection. A take-down. Shorter than the Bear and beefed up to 60 pounds. I twisted alternating-colored strands of B-50 for a string that gave a deeper level of class to the setup. It showed its worth with hogs and whitetails for several years before I put it on the rack for safe keeping. The longbow concept had caught my eye.

Kinton and what he considers his last whitetail with a traditional bow. This is the same Osage used on Texas hogs and the South Africa nyala.

Some might question the step backward from recurve to longbow, and there is an element of legitimacy in such query. The recurve is, in some level of thinking, more advanced and efficient, and the recurve is certainly shorter. But, oh, that romance again. The longbow is an elegant unit that goes back to the far recesses of archery’s history. A stick and a string, if you will. Antiquated. No frills. And I have grown to appreciate the design more than any other.

I began picking up a longbow at every opportunity presented and sending arrows to a target, that whispered cast endearing itself to me with each shot. I must have one. The first I actually owned was one I built. Wood laminates sandwiched between fiberglass. I made several, the last the most striking piece of handwork I ever did. A shapely grip of three contrasting woods, decorative Bocote under clear glass, limb tips of two woods. It yet holds a position of reverence. Still, my rearward trek had not reached its climax. The all-wood selfbow must follow.

The Selfbow

The selfbow is an embodiment of intrigue. In the hands of practiced archers, it became a formidable implement of battle. It was and is now a steady and stately method of feeding oneself. A simple piece of wood – Osage is grand – and a twisted string. Perhaps a shallow shelf appended to or cut in the grip. Occasionally backed with rawhide or sinew or fabric or snake skin. No gadgets. That romance again emerges.

Kinton took an Osage selfbow to Africa in search of nyala. He found time one day to hunt guinea fowl and francolin.

One memory-filled afternoon found me in a treestand overlooking a trail that crossed a skinny and serpentine ridge. That ridge grudgingly but quickly gave way to a precipitous drop which ended at a soybean field. That same ridge housed oaks, their acorns littering the ground. An Osage bow backed with a supporting strip of bamboo was with me, as was a quiver filled with heavy Port Orford cedar arrows tipped with wide and sharp two blades. A chubby doe stopped to grab an acorn, some of her comrades already racing to the beans. That doe never reached the soybeans.

And one turbulent morning following a night of thunderstorms in the Texas Hill Country, I strung an Osage – no backing – and left camp for one last try before departure. A heavy north wind blustered through the mesquite. Then a sounder of hogs. A minor adjustment in my approach tactic and I was there, 20 yards from completion. I much enjoyed the pork loin and sausage.

The author poses with a Texas hog he took on a blustery morning.

Then there was South Africa. Limpopo Province. That same bow and arrows used in the hog hunt were in hand in those mystical tangles of sickle bush and thorns. There were naysayers about. Several opined their misgivings, concluded it couldn’t be done. What with the walk-and-stalk method and the flightiness of the nyala and all such. But it could. A fine bull. No huge specimen but well earned. And I am truthful when I say regarding situations such as this that size really does not matter.

This nyala bull traveled no more than 30 yards after the arrow hit.

Finally, that one bow and those cedar arrows rested across my knees near an oak when four whitetails showed. All bucks, all of near-identical size. I chose one. The arrow zipped to target; the buck made it downslope 60 yards. He was my last buck with a selfbow to date. And I regretfully suspect he was my last with any bow, as you shall see directly.

What’s Next for This Bowhunter?

So by that time, the time of that last buck a half-decade back and three decades ahead of my first selfbow, I had declined to the perfect stage of mellowness, to pure tradition, to the point of no return regarding equipment. But not only equipment. That declination has now become evident in aging. One shoulder repaired at great expense of funds and healing time. The other begging attention, about which the kindly doctors are not jubilantly hopeful. And I am not predictably surefooted as I once was. I prefer no longer to leap tall buildings in a single bound or blissfully scale lofty peaks of wonderment. Nor climb treestands.

Now what? Lacking omniscience, I have no prognosis. Only God knows the certainty of such concerns. But I am convinced that I thrilled to and was engulfed by the meanderings of a bowhunter. Convinced that I chose the proper path for the sensibilities belonging to one such as I. And unlike the activity in its purest form as I once knew it and scarce believe I can again participate in, the memories will survive a bit longer. I shall sedately but joyously celebrate those memories, memories of my declination of a bowhunter.

Photos by Sam Valentine

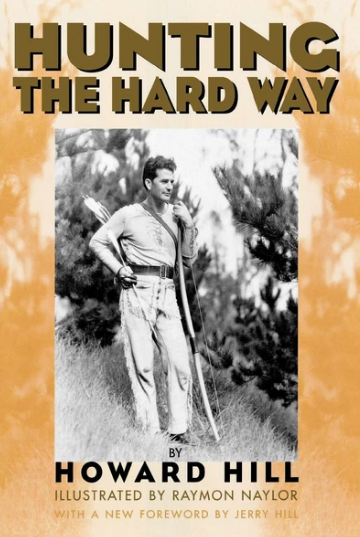

Archery conjures up many images―bowhunter Robin Hood, the American West, wild safaris in Africa and the simplicity of nature on a brisk October morning. Howard Hill brings to life all of these images with exciting stories about the thrill of the hunt, oneness with nature, and the adventure of the great outdoors. Hunting the Hard Way, considered by many to be the most sought-after archery title, is now back in print and full of the thrilling escapades of a bow and arrow purist. Thrilling stories include bowhunting wildcats, buffalo, mountain sheep, wild boar, alligator, deer and small game with bow and arrow. Shop Now

Archery conjures up many images―bowhunter Robin Hood, the American West, wild safaris in Africa and the simplicity of nature on a brisk October morning. Howard Hill brings to life all of these images with exciting stories about the thrill of the hunt, oneness with nature, and the adventure of the great outdoors. Hunting the Hard Way, considered by many to be the most sought-after archery title, is now back in print and full of the thrilling escapades of a bow and arrow purist. Thrilling stories include bowhunting wildcats, buffalo, mountain sheep, wild boar, alligator, deer and small game with bow and arrow. Shop Now