Havilah Babcock, a beloved English professor and department head at the University of South Carolina, has been frequently described as the partridge’s unofficial poet laureate.

“Call him Bob White, quail, bird, or whatever you will in the rest of the country,” he wrote, “but to elder sportsmen of the South, this saucy little patrician is still partridge. It is lese majeste to call him anything else.”

Semantics aside, anyone who delves into Babcock’s writings is opening a door to enchantment. In five anthologies containing his sparkling tales—I Don’t Want to Shoot an Elephant, My Health Is Better in November, Tales of Quails ’n Such, Jaybirds Go to Hell on Friday, and The Best of Babcock (edited by Hugh Grey, who published many Babcock pieces in Field & Stream, along with his only full-length sporting work, The Education of Pretty Boy)—he left posterity a lasting literary legacy.

Strangely enough, the origin of Babcock’s grand tales came from chronic insomnia, and he turned pen to paper during morning’s wee hours in a fruitless search for an antidote. He may have suffered mightily, but that sleeplessness left us a bounty of immensely enjoyable and insightful tales devoted to the bird he fondly described as “five ounces of feathered dynamite.”

As might be expected of someone who served as the head of a university English department for decades, Babcock was a master of words and a masterful wordsmith. Just reading the titles of his books whets the literary appetite.

Babcock pursued quail with an abiding passion, sometimes dismissing classes during the heart of the bird season in order to spend a full day afield. Over the years he hunted with everyone from simple country farmers (often those who conveniently happened to have access to prime bird habitat) to nationally renowned figures such as Bernard Baruch.

All evidence suggests he was as delightful a hunting companion as his writings are a joy in armchair adventure. Unquestionably, he had a rare knack for detecting and describing all that was good and gracious, magical and mesmerizing, about the quail hunting experience.

Take what he says, for example, of eager anticipation associated with a staunch point: “The tense second before a whopping covey explodes is the most nerve-wracking silence in history.” Or ponder with amused wonder and a knowing nod of agreement his thoughts on a young dog’s first hunt: “No man can follow a rollicking, bungling, and over joyous pup all day without laughing a lot and crying a little.”

Like a pup, Babcock was eternally youthful in outlook and optimistic in expectations whenever he hunted. Setting out at dawn amidst a million diamonds of frost sparkling atop stalks of broom sedge was for him “a quiet miracle bringing balm to the spirits.” Each sunrise, “forever old and forever new, always and never the same,” buoyed his spirits and put a spring in his step. He understood and appreciated the finer points of canine and human companions, reckoning that “modesty is the first requisite in a shooting companion” and knowing the distinguishing characteristics that defined an exceptional bird dog.

Dogs which found, pointed, and held birds in splendid fashion merited modest praise for their competence; those that then retrieved well achieved excellence.

“A beautiful retriever,” he wrote, “is like a virtuous woman. Her price is far above rubies. Retrieving . . . makes the difference between a good dog and a great one. It is the icing on the cake, the cherry atop the sundae, the lace on a bride’s pajamas.”

Maybe the simplest way to appreciate his genius and geniality is by sharing one of many anecdotes passed on by two generations of mesmerized students who sometimes stayed on a waiting list for his vocabulary class, “I Want a Word,” for as long as five semesters. Babcock rushed into class one morning clad in Duxbak attire and obviously with a mission in mind. Hurriedly scribbling “Dr. Babcock will not meet his classes today” on the chalk board, he headed out the door to his jalopy and a day afield. However, just as he reached his vehicle, the sporting scholar realized he had forgotten the two boxes of shotgun shells, which were in his desk. Upon returning to retrieve them, he noticed a goodly number of undergraduates still hanging around, and they started tittering when they saw him.

A glance at the blackboard revealed why. Some quick-witted student had altered his hastily chalked message to read: “Dr. Babcock will not meet his lasses today.” Without breaking stride or betraying so much as a hint of emotion, he grabbed the shotshells in one hand and an eraser in the other. One swipe of the latter altered his message in meaningful fashion by removing the “l” in lasses.

As deep a thinker as he was quick of wit, Babcock felt the finest legacy a man could leave his grandson was “a good gun and a good bird dog.” Thankfully, he left the rest of us far more in the form of scores of stories as enduring as they are endearing. To read them is to be transported vicariously into a quail-hunting world filled with wonder with the erstwhile Dr. Babcock as our guide. Short of whirring wings in the air and the smell of gun smoke drifting across the landscape, one could scarcely ask for more.

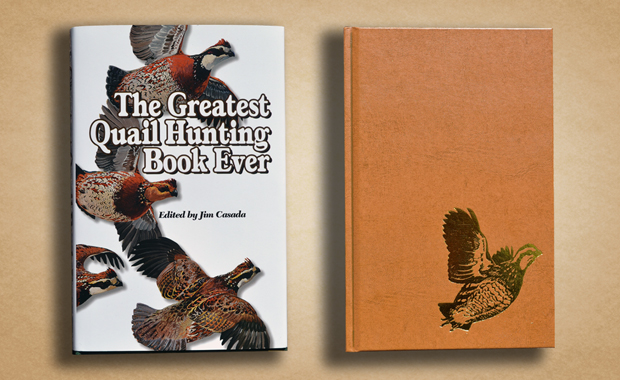

Babcock is one of the excellent outdoor writers featured in Sporting Classics’ new The Greatest Quail Hunting Book Ever. This fascinating 400-page anthology features 40 stories from those halcyon days when sporting gentlemen pursued the noble bobwhite quail with their favorite shotguns and elegant canine companions. Click here to order now!