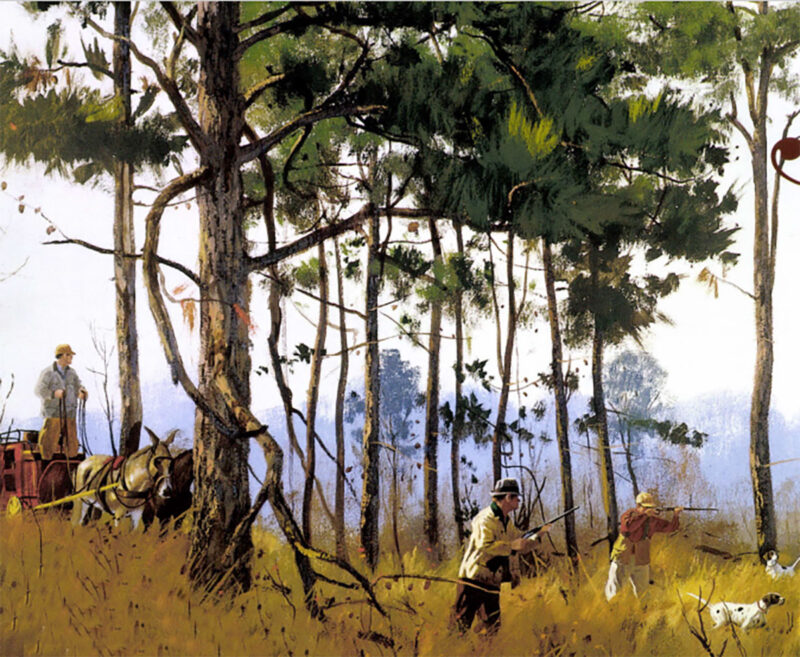

It was boots and chaps. Gents and hats. Shotguns and spats. It was dog-folks gentle and gay. It was dignified old live oaks, bearded grizzled and gray. It was a lazy old mule wagon, creak rattle and sway.

“The Lord’s own symphony,” my Grandma Betts would say, “in the miracle of two notes.”

He was the concerto of Spring, the sonnet of Summer and in November, when the opus fell to the vesper of a covey-call, the sonata of Fall.

He was family before I ever hunted him. A brother now and then. Folks were still War-worn and depression poor. What humble earthly possessions they enjoyed were largely Heaven-sent, the product of a God-fearing persistence and existential toil. Of the modest few things that afforded them pleasure, none was more beloved than a Bob and a covey of quail. Most everybody had one. Little homebodies that were hip-pocket kin, that eked a mutual living from the small garden plot at the stoop of the woods, that abided in the honeysuckle corner of a split-rail fence, or resided in the blackberry briers at the make of the corn rows. Unlike the field bevies that harbored in the ragweed fallow of the small, quilt-work farms , they were never hunted. Without a word of barter, it was principle, understood and respected. Old horses carried yet the scars of the Civil War, banishing ever again the discord of blood-agin’-blood. He and his small tribe were family, and family was to be protected — nurtured and sheltered — held to the heart.

We’d rock on the porch in the late of the afternoon, near evening, after the sun bade quitting time. There’d be a golden wash over the meadows, yellow sunflowers on the hillside that stepped to the creek, a blue haze on the cap of Burkhead Mountain. The air would be warm and liquid mellow, the breeze mostly spent, the farm shushed to quiet. Granny would be humming softly and shelling peas; Granpa drawing on his pipe, mending in his lap the dilapidated harness the mules wore. I’d be sunburned from a day-long odyssey on the creek, puckered in places from giddy hours of dog-paddling the swimming hole, tuckered from the scamper of my spirit.

We’d rock on the porch in the late of the afternoon, near evening, after the sun bade quitting time. There’d be a golden wash over the meadows, yellow sunflowers on the hillside that stepped to the creek, a blue haze on the cap of Burkhead Mountain. The air would be warm and liquid mellow, the breeze mostly spent, the farm shushed to quiet. Granny would be humming softly and shelling peas; Granpa drawing on his pipe, mending in his lap the dilapidated harness the mules wore. I’d be sunburned from a day-long odyssey on the creek, puckered in places from giddy hours of dog-paddling the swimming hole, tuckered from the scamper of my spirit.

He’d join us about then. From the edge of the garden, his little song would rise onto the prayerful respite between done-and-dusk like Gabriel’s Horn, collecting each of us in the space of its travel, soliciting us one-by one to pause and listen. Clear and promising as a church bell on a country Sunday morning, it would spend itself about the heath of home, while our souls rushed to embrace it . . . like wildwood religion. Anxiously we’d wait the moments by, until it would soar again, reseeding our plain and needful world with simple peace and harmony.

BOB-white!

Most everybody kept a country bird dog then. A rag-tag setter, or a ribby, double-nosed pointer. A Lady or a Luke, a Sally or a Ben. Rarely in a kennel, but a little more convivially than the Beagles and the hounds; perhaps on an old jacket under the shade of the porch, or on a rope or a chain, by a propped-up barrel under a mulberry tree. At best, in a patched-up, make-shift run off the back of a heifer shed, that sometime before was a chicken lot. Same as not, the most and happiest of them ran free.

A few had “papers.” The majority were simply certified under the considerable auspices of a man’s pride. Always the “drops,” of course, the erstwhile progeny of the time Ol’ Mack went a-callin’ on Sam McBride’s good gyp Princess, the blood-get bookmarked illegitimately between proof and prejudice, and culled to a spare survivor or two, one for a man. Brag dogs eventually, light on looks but long on bird sense, that oftentimes amounted to the better of both breeds. By the time they were three or four, many old bird dogs had fared only slightly healthier than the hounds, running lean through the ribs and being snake-bit or hog-gouged one-time-or-another, carrying the stuffed hide or proud flesh to prove it.

I know now there were folks “yard training” back then, replicating into a dog’s head the learning that summed to “Come,” “Heel” and “Whoa.” It’s just that I nor any of us in Cedar Grove Community ever knew or heard anything much about it. Mostly, to us, it amounted to hollering “Jake,” and throwing a ham-hock out the back door. If you wanted a bird dog, come October you simply hooked a seven-months puppy up with his mommer or popper and took him bird hunting. He came if he wanted to go, and he stayed close if he wanted to get his mouth on a bird, and he learned to point and stand by watching the old hands go about it. What they didn’t teach him, the birds, a keen hickory switch and his good instincts did, and pretty soon he was a sure-enough bird dog.

Birds were as plentiful as swallowtails on butterfly weed and if he paid proper attention it didn’t take long before they put the numbers in his head. Quail mostly walked or ran where they went then, unconditioned to the present day proclivity of flying in-and-out to their dinner, rather casually meandering from roost to breakfast, to preen and dust, to supper, and back home to bed again. An upcoming youngster told you he had the arithmetic right when he started trailing, out of the field and off down the hollow, or across the woods, roading and stiffening as the scent got better. He might run over a bevy a time or two when he didn’t get the wind right, but before long he’d stop them between run and roost, pin them for the count. I’d go with my Uncle Joel and watch the old wisdom dogs do it at deep twilight, in the green briers — hard by the sulfur smell of a swamp bog — with the bloated, buttery globe of a Hunter’s Moon just rising, shimmering on the catch-water between the spooky black stumps of the old dead trees. About the time the owls started calling. To shoot the birds you had to bend on your knees, catch them fading against the silvery window of the sky.

There are times I miss those old dogs. I suppose by today’s standards they were a motley lot, short on refinement, breeding and manners, a makeshift mix of mustard-and-mischief. But there was one thing, Mister. What they gave up in rough, they made up in ready. They were Honest-to-Betsy, God-and-good golly, oldtime “bud” dawgs. Old dawgs that hunted up and “p’inted” quail. That put the “reckon” to rest and birds in the bag.

Under the Christmas tree the year of my thirteenth birthday were three gifts that in good part set the course of my life: a Single-barrel Winchester shotgun, a box of Peters Number 8s and an Irish setter pup. The Winchester and the shells I had suspected; the pup I had not.

Maybe it was the beauty of the beast. Maybe it was Kjelgaard and the intoxicating saga of Big Red. Perhaps it was the echo of a few old-timers who remembered the red dogs from their glory days, when they were bred purely for the field and a good one could toe scratch with the greatest of the gunning breeds

“Best I ever had,” the old hands would say, with a longing in their eyes . . . “best I ever saw.”

“Best I ever had,” the old hands would say, with a longing in their eyes . . . “best I ever saw.”

How else might you suppose so many youngsters of the forties and fifties came up with an Irishman as a first birddog? Except mine was a lassie: seven weeks old, eyes baby blue, fairest I ever knew. Santa Claus had hidden her out in a blanket and a neighbor’s grain bin until Christmas Eve. Daddy had then whisked her in under his coat after I agreed to bed, and tucked her through the wee hours into the warmth of his underarm less she should cry or whimper. It was the lone and only time he ever suffered a dog to covers.

Now here she was, Christmas lights in her eyes — baby coat the fuzzy orange of a kit fox, little pot-belly pokey and pink — tiny paws hooked over the lip of a big white giftbox, scrambling desperately with hind legs to push over-and-out. Around her neck was the bow from a bonnet, about her a nest of green tissue paper, and altogether she was the prettiest sight a boy could ever design to see. Dumb with wonder, I looked to my folks and back again to the pup.

“In Dublin’s fair city . . . where girls are so pretty . . . I first set my eyes on sweet Mollie Malone.”

Mama began singing. Funny, how crazy little things like that can embellish a remembrance so beautifully for a life time.

Unsuccessful at escape, my little miss was wailing what-for. Hardly Christmas music. Lifting her gently from the box, I nestled her against my chest. She promptly reared in my arms, kissing me profusely in the mouth.

“Mollie wouldn’t be bad,” Mama said.

I thought for a time, between kisses. I was infatuated with Debbie Reynolds along then, the Tammy movies.

“Tammy,” I said, “it’ll be Tammy.”

I didn’t know any more about naming field dogs then than I knew about women. Or maybe I did. But what I knew I forgot. Females do that to you. A lovely mahogany lass my fuzzy orange pup bloomed to be. Sunlight splintered into fiery bolts of auburn when it touched her coat, and her hazel eyes blazed with desire.

By the time she was 13 months, she, me and the Winchester had made the rounds of most every covey in the community. My Grandpaw, several uncles and three neighbors were complainin’ the birds “sho’ were wild this year,” but as yet nobody could figure why. Cause we were reasonably discrete about the matter, not exactly sneaking around, but not announcing it neither.

Knowing they’d set a foot down. Boy or no, a man’s birds were like his wife; you didn’t go around courting them on the side.

Truth was, we hadn’t pointed many, and had shot less, but there’uz no denying we’d put the fear of God into ’em. M’Lady had run through them all. But once she discovered she couldn’t catch them, she’d flash pointed a time or so, and I had borrowed the good fortune to kill a single or two for her, where they got up wild. So that one lovely afternoon in December, she stood a bit longer than she meant too on Hettie’s Hill. Instinct did that to her, stoving her Stiffly against the silvered ragweed edge of a ragged brown corn patch. Her eyes bugged, and her tail stopped poker-stiff. The drooping winter sun spilled in, painted the world orange and mellow, and set the resin aglow in her coat and feathers.

“Whoa,” I said impatiently, and crept in ahead of her, the Winchester trembling to Port.

Fifteen old-timey quail clattered sky-bound against the silver weeds, leveling right and left. I can’t remember time to pick a bird, but there wasn’t nobody else there to be polite about, so I could shoot at will. Some how I managed to get cocked and ahead of one. The little gun spoke and there was a tiny burst of feathers, and a set of russet wings went limp and tumbled into the stubble. About the time Tammy got her mouth on that one, a straggler sputtered up, and I turned my pocket inside out, dumping three shells on the ground to the one I fumbled into the gun. But I knocked it down too, shy of the woods line.

Not long afterward we made Grandpaw’s dog string.

“Sakes and Sally, Boy, you done played hob on every covey in three mile. Best you and that red dog stay along with us, where we kin keep one eye on you.” Grandpaw smiled when he said it.

Me and my dog smiled back.

His name was “Shot.” Hardaway Delivery’s Shot to be up-town about it. That was a mouthful just to call a dog, I thought. But he was a good-looking somebody.

A strapping liver-on-white pointer, he stood high on his toes — about five hands at the shoulder — and he belonged to Mister Ralph Briles. Mister Ralph asked could he run Shot on my Uncle Sid’s farm, so we met them there early one Saturday morning in October, with the painted leaves glowing behind the mist like splotches on an artist’s palette.

Mister Ralph not only brought his dog, but a big, black walking horse. The gelding banged off the trailer, threw his head high and blew like a deer snorts. Then he pranced around stiff-legged about four times, with his neck and tail cocked. Danged if I would’ve gotten on him. But Mister Ralph tied him off and threw the saddle over him.

Uncle Sid didn’t say anything about it, but Mister Ralph sure was dressed fancy. He had on his riding jodhpurs and leather knee boots, a jacket and a jaunty felt hat. He stuck a shotgun in the saddle scabbard, and corded out his dog.

“Where do you want to start?” Uncle Sid asked, and Mister Ralph looked off about the distance, said, “Well, it’s more where we hope he’ ll finish.”

Mister Ralph steered his dog to the edge of the field, Shot straining against the lead, the veins in his neck and legs bulging like mole trails.

“Whoa,” Mister Ralph said.

Shot slammed stopped like he’d hit a wall. He had this keen look in his eyes, and if somebody had struck a match, I think he would have gone off like a powder keg.

Mister Ralph climbed on the horse, fingered a whistle. The gelding was dancing, leg-to-Ieg. Shot trembled like he was cold.

All of a sudden, Mister Ralph loosed a mighty blast on the whistle, and Shot scalded away like a cat with turpentine on his tail.

“Yeeeowwh.” About the time Shot hit the first corner, Mister Ralph squalled and lifted the hair on my head. Shot whipped left and sailed on. Uncle Sid and me jumped in the jeep and followed Mister Ralph on his horse, not hide-nor-hair of the pointer for fifteen minutes. He’d done run by every bird on the farm , and I thought he was gone for good. But then Uncle Sid saw a tick of white way yonder on the hill.

“Is that him on that hill?” Uncle Sid said to Mister Ralph, who was sitting kinda downcast on his horse.

“Whooohaw.” Mister Ralph yowled, his face lit like a Christmas candle.

“Looks like he’s peeing on a bush,” Uncle Sid said.

“Bush, hell,” Mister Ralph clamored. “He’s pointed.”

We chased Mister Ralph fast as we could, him galloping ahead on the horse.

Shot was standing like one of the statues I’d seen at Brookgreen Gardens the times we’d been to Myrtle Beach. Mister Ralph climbed down, jerked his shotgun out of the scabbard, walked out front of his dog and kicked the birds up. Then he did something really peculiar. Rather than shoot at them, he just stuck the barrels up and fired into the air. Shot hadn’t wriggled a whisker — his tail jacked tight and his head cloud-high — watching the stragglers away.

Altogether, Uncle Sid remarked, it was the strangest thing he’d ever seen. Strange, maybe, but it sure was pretty. I didn’t know when I’d ever afford the horse, but one day I meant to have me a dog like that.

We got her about a week before I left for the Army, the first “promise and keep it” quail dog I bought on my own. Prudence said I should have waited, but I never liked the name Prudence nohow. Loretta and I were sleeping between the same sheets, about the only two we had, renting a little house in Cary, and we had scrimped for a year at the means to buy a pup.

I wanted an English setter, white with blue ticks. There was a man name of Quay Johnson kept some a piece down the road, and she picked us alone from a litter of eight.

I wanted an English setter, white with blue ticks. There was a man name of Quay Johnson kept some a piece down the road, and she picked us alone from a litter of eight.

We called her “Bess.”

But then I had to go off to war at a place called Fort Benning. It hurt like sulfur after sin, ’cause November was coming and the nights were delicious chilly, and the pea patches were yellowing in the fields. I had a new pup and I knew where at least nine coveys of birds were within a trot of the house. We were honeymoon happy, Loretta and I. She would go training with me, and she and I and our speckled pup could have gamboled bevy-to-bevy with autumn in our nose.

Instead, I had to kiss them both “Good-bye” one glorious day in October, climb on a bus and go off to be cussed amid some Godforsaken huddle of Quonset huts, by some gimlet-assed, little Yankee Sergeant from Jersey.

Bess grew up with Loretta in my stead, sharing her bed and waiting out her work day in Animal Husbandry, at N.C. State, wreaking puppy havoc in the house and welcoming her home each night to see. Through all, Loretta loved my dog as much as she loved me. I earned a furlough for sharp shooting, another for surviving and I made off home each time hard as my thumb would carry me, to my wife and my dog. The fields and the birds. I wanted to hate the bureaucratic bastards that conscripted me away from them long as they did, but I guess I was a little proud I went too. Then one day I got discharged, a First Sergeant from Sill, and was home for good. We were a family again, the three of us, and the uplands had waited, the scented bottoms and the golden fields and the quail that homesteaded them. After a while I began to forget the spite, and stand on the spirit.

“We abhorred the days you were away,” Loretta said, “but never the reason you were gone.

We’d lost time. Bess had grown amiss, a beauty in need of a ball, and I escorted her to many, near and wide. What I couldn’t, the swamp birds taught her. She pointed and held the ghostliest of them for keeps one dusk, on the edge of a Johnston County bog. She turned up lost and I looked for her 20 minutes, night falling — found her buried up in reeds and greenbrier, the roosted covey wadded up before her nose under twilight. Inkspots flung briefly against the faint blue pane of the sky.

Whoom. Whoom.

I heard the splash; didn’t see the fall. heard the crash and clatter of the water, as Bess bounded out to search. Back with the sodden cockbird, she laid it to my hand. I could hardly see the highlights in her eyes. “I’m glad you’re back,” they said.

She proved it many times over, the next five years. Raised me out of knee pants, and made me a bird hunter. Until one dreadful afternoon in December, on that same Johnston County farm, she fell suddenly ill. Staggered, and I ran carrying her the half-mile back to the truck. Two days later, there eventuated the horrible truth of a tumor, and two weeks after that she was dead.

She kept a part of me life can never give back.

From his back door, the old man had but to put a foot to the stirrup, whistle away a stout foursome of bird dogs, enjoy the bountiful venue of the little farms. Anyone of which welcomed his passing, for he was kind, generous and well-liked among the folk who lived there, delivering especially upon the eve of Christmas and the New Year gifts from his saddle bags. Or sending around a wagon of warm wishes from his cupboard.

He was about the last of his kind in our part of the country, where once there had been many, and I’d see him ride by, lift a hand. Four fleet dogs testing the fields ahead of the horse. Once, in the distance, I actually saw them stop, near a gallberry head, dead tight in the distance. First one, then another behind him, drawing up until they were stacked against the tawny Autumn landscape like the ones I’d seen on the Remington calendar on the wall of the Harvest Milling Company in town. Saw the old man get down, pull his gun, walkup and take the birds . . . whump . . . whump. And one of the dogs when he released them, running out to punch the grass with his nose, gather up a bird and recover it to the old man.

How I had envied him, and dreamed endlessly of doing the same, and now finally I was. Maybe I didn’t have the mansion yet on the hill, but I had the horse, a good Parker gun in the scabbard and three spanking-fine dogs. There they were, way out front — pretty as Paradise — and I no longer had to imagine. In ten more years the country would close down, and my little window in time would fall shut just as his had, and I would have to motor to Georgia and Texas to find what semblance was left. But right then, I had managed the time warp.

The Swamp Fox Classic, flagship event of the Swamp Fox Sportsmen’s Club of Charleston, was that year a class stake of 15, trial-seasoned youngsters, over a lowcountry shooting dog course that demanded nothing less than their best.

Medway was the old South, a gift to gentlemen at the grant of a King. An aura of big house and boxwoods, mists and magnolias, grace and three centuries. A place of mood and magic, a pause of wish and wonder.

It was the rhythm and stroll of a good walking horse, over an avenue 200 years to dust under the hooves of a thousand others. It was boots and chaps. Stirrups and straps. Gents and hats. Shotguns and spats. It was dog folks — gentle and gay. The stiff, sharp scent of newly crushed bay. It was dignified old live oaks, bearded, grizzled and gray. A lazy old mule wagon, creak, rattle and sway. It was the shiver in the silver of dawn, the sparkle off frost in a fresh Dixie morn. A storybook trip through a time warp of piney-woods and short grass behind one more generation of fierce young pointing dogs, and completing it all was the reality that three of them were mine.

It was the rhythm and stroll of a good walking horse, over an avenue 200 years to dust under the hooves of a thousand others. It was boots and chaps. Stirrups and straps. Gents and hats. Shotguns and spats. It was dog folks — gentle and gay. The stiff, sharp scent of newly crushed bay. It was dignified old live oaks, bearded, grizzled and gray. A lazy old mule wagon, creak, rattle and sway. It was the shiver in the silver of dawn, the sparkle off frost in a fresh Dixie morn. A storybook trip through a time warp of piney-woods and short grass behind one more generation of fierce young pointing dogs, and completing it all was the reality that three of them were mine.

I was recently returned from Oklahoma, had just talked to a friend who’d hunted Iowa, Texas and Kansas. Another back from Mexico. I was parleying all this to an old South Georgia dog man, espousing the virtues of a good Texas quail year.

He listened cordially, turned his head and spat copiously. Pushed his hat back, past the reddish tan-line on his pale forehead.

“They’s birds in Texas,” he agreed, “but they ain’t gentlemen.”

“Red is the rose, that in your garden grows, and fair is the lily of the Valley . . .”

Back in the kitchen, Mama was singing again. Time had turned. There was the gray in her hair, like the winter on the years. The years that had finally seen me home. It was Springtime, near dusk, and I sat on the back porch of the old homeplace. Looked and listened. There, still, by the garden was the rose; gone, the little two-noted voice that caused it so deeply to blush.

Hard for us old hands, brought up with Bob, that you have to lose so much to gain so little.

The social pundits like to crow that our standard of living is better than it’s ever been. I suppose if you’re content to measure it simply in dollars and dalliance, it’s hard to deny. Though in more unfashionable parameters I think of Granpa and Granny — the folks back when — that toiled dawn to dusk and never had more’n a hog and a hedgerow. But in the hedgerow, thick or thin, they had a family of Bobs. And nary a one of ’em ever knew he was poor.

Life can be likened to ascending a mountain. The higher you climb, the more years you have beneath you, the farther you can see, the more unobstructed the view, the more you understand.

Life can be likened to ascending a mountain. The higher you climb, the more years you have beneath you, the farther you can see, the more unobstructed the view, the more you understand.

From A Higher Hill finds Mike Gaddis atop the enlightening vantage of almost eight decades. Looking back over the vast and enthralling sporting landscape of a life well lived. And ahead, to anticipate and savor whatever years are left to come. Buy Now