Perhaps the only art form to originate in America, the decoy is, in essence, a historical document of our golden age of waterfowling.

Hunting was a very normal activity for young adolescents where I grew up in rural middle Georgia. We started with rabbits and squirrels and progressed rapidly to white-tailed deer, quail and ducks. When I completed my doctorate and moved to the coast of Georgia, waterfowl hunting became my passion. I chased ducks from Maine to Florida.

I was also “born to collect.” By age 10 my collecting gene had crawled out from under its chromosome and was exerting influence on my daily life. Arrowheads, bird feathers, snake skins and the like crowded my shelves. At age 25 I was heavy into hunting books and related trappings of the sport.

Then one day, while being a considerate husband, I followed my wife, Martha, into an antique shop. Here I made a discovery that would forever change my life. Sitting in the corner on a nail keg was an old hand-carved pintail duck decoy. For $10 it was mine, and as they say, “the rest is history.”

For me, decoy collecting is a natural outgrowth of the sport of duck hunting combined with the collecting mentality. That’s probably true for 90 percent of the first generation of decoy enthusiasts. Included, and often one and the same with this group, are those who are interested in the Golden Age of Wildfowling. They love to read about those halcyon days, collect memorabilia of the period and even visit the old shooting grounds of the former market hunters. For them, decoys are historical documents.

The other group of collectors who have made quite an impact on the venue are those who see the decoy as folk art; many claim it is the only art form created in America.

Originally intended as utilitarian objects—i.e., tools of the hunt—decoys were produced to help hunters obtain sustenance and later to help market hunters earn a living. When waterfowl were plentiful, most any wooden likeness, no matter how crude, would fool their living counterparts. But for many carvers, “good enough” was not good enough. They labored continuously to improve their counterfeit birds, to produce better paint patterns and to even animate their lifeless blocks of wood. The result of many craftsmen’s creations was art that truly captured nature.

Hundreds of thousands of decoys were carved between 1840 and 1950. But in 1918 legislation passed by Congress outlawed the interstate sale of migratory birds, bringing to a close the era of the market hunter and curtailing much of the need for decoys.

By the mid-1950s mass-produced plastic decoys essentially brought to a close the age of hand-carved wooden birds. A few craftsmen continued to ply their trade, outfitting those few hunters who remained committed to hunting over wooden replicas. Many other carvers turned their talents to producing more decorative birds.

Thanks to these two groups passing their skills along to later generations, there are many wonderful decorative pieces available today for our enjoyment. And there is a large following of enthusiasts who collect only these contemporary birds. They are not to be confused with decoys, but are wonderful pieces of art, nonetheless.

In 1934 Joel Barber wrote the first book on Wild Fowl Decoys. At that time few had ever imagined the wooden bird as an object of art or history worthy of preserving. In fact, thousands were burned in wood stoves or thrown out to rot as a result of the laws forbidding market hunting and the development of plastic replicas.

In 1965 William J. Mackey, Jr., the godfather of decoy collecting, published American Bird Decoys. Also in 1965, Adele Earnest published The Art of the Decoy: American Bird Carvings. These wonderful, engaging books rapidly opened up the world of the wooden bird to would-be collectors. Their numbers grew rapidly over the next four decades, a period that has witnessed more than 100 books written on American duck decoys and the related wildfowling for which they were used.

Several companies were also created to offer decoy auctions throughout the year. Three of the largest are Guyette and Deeter’s North American Decoys at Auction, Copley Fine Art Auctions and Decoys Unlimited. They each produce illustrated catalogs that serve as excellent educational material for the new collector.

Throughout the 1960s and ’70s, when collecting was really surging, those who lived in areas where millions of waterfowl wintered and the thousands of hunters pursued them were at a great advantage. Many areas like the famous shooting grounds of the Susquehanna Flats were ripe for the picking, with thousands of decoys stacked in attics and barns. But by the ’80s and ’90s most of the great discoveries had been made. Although a few still occasionally emerge, collectors now obtain most of their birds from auction houses and dealers, of which there are many.

One of the greatest pleasures I have in collecting is to acquire a decoy produced by a maker with whom I am not very familiar. To then research the history of that carver through published work or the Internet gives much enjoyment and added value to the bird.

By 2007 prices had escalated to such an extent that few young collectors were entering the hobby. In that year a Lothrop Holmes red-breasted merganser sold for $856,000, the present world record. The first million-dollar decoy was just around the corner, or so most thought. Then 2008’s Great Recession hit. The value of everything plummeted, particularly luxury items. And as a collector friend said, “You can’t eat decoys.”

Like housing, decoys were in their own inflated bubble, and a big correction was coming. Although tough for many collectors who had paid exorbitant prices for numerous birds, there was a silver lining in the downturn. Many high-quality decoys that had grown out of reach for new collectors were now obtainable. There are many fine decoys in original paint and physical condition that now sell for under $400 and countless more under $800. This phenomenon is creating growth in the number of collectors—a good thing.

Decoy prices vary according to many factors, starting with form and rarity. The merganser mentioned earlier had both. Also important, but not overshadowing the first two criteria, would be original paint and physical condition. Age and attribution also affect prices. It stands to reason that if a carver was working in 1880 and only produced 100 birds, all with great form, one of his decoys would be much higher valued than a factory-produced bird in 1920 that is one of a 1,000 similar examples.

The recession saw some decoy values dip more than others. For example, Mason factory decoys (1896-1924), which were turned out by machine but hand painted, took a significant hit. Many thousands of ducks, geese and brant were produced in four grades: premier, challenge, glass eye and standard, and each bird in each grade was carved and painted to look exactly alike.

Mason decoys continue to be excellent collectibles, but don’t expect to see the lower grades or more common species to achieve lofty prices for quite some time. But as I said, the silver lining is for the new collectors.

Anyone considering the purchase of one or two decoys should certainly subscribe to Decoy Magazine, published in Lewes, Delaware. Its articles are wonderful, informative reading, whether you are an avid collector or just interested in the wonderful history of wildfowling.

At age 76, I don’t rise at 3 a.m. and venture out into the marshes as much as I once did. But the passion is still there, thanks to these timeless, counterfeit works of American art.

Editor’s Note: For four decades Dr. Lloyd Newberry has been writing hunting and fishing stories chronicling his many adventures in 67 countries and provinces. Three of his prior books include Pages of Time: Memoirs of a Southern Sportsman, The Big Five of Africa and European Hunter: Hunting 33 Countries in the Old World.

Newberry’s newest book Wings of Wonder: The Remarkable Story of the Cobb Family and the Priceless Decoys They Created on Their Island Paradise is illustrated with over 500 beautiful and some very rare photographs the book is over five years in the making. Published by Sporting Classics, the new book will be available this November in the Sporting Classics Store.

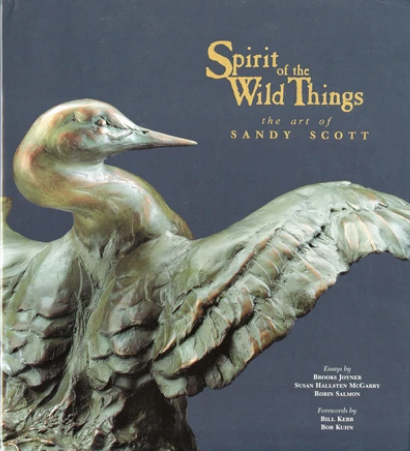

Sandy Scott is widely recognized as one of the country’s premier animal sculptors and printmakers. Spirit of the Wild Things includes examples of Scott’s popular etchings. Concise, colorful captions express her immediate thoughts about the creatures to which she gives form. A detailed Chronology identifies the major events that have impacted the life and art of this 20th century animalier whose bronzes cry out to be loved, admired and respected – to be touched with the hand and the eye, with the mind and the heart. Buy Now

Sandy Scott is widely recognized as one of the country’s premier animal sculptors and printmakers. Spirit of the Wild Things includes examples of Scott’s popular etchings. Concise, colorful captions express her immediate thoughts about the creatures to which she gives form. A detailed Chronology identifies the major events that have impacted the life and art of this 20th century animalier whose bronzes cry out to be loved, admired and respected – to be touched with the hand and the eye, with the mind and the heart. Buy Now