Blacktail hunting in California vineyards is an uncommon pursuit because California vineyard blacktails are an uncommon animal.

Texans have a saying. Don’t Californicate Texas. Keep your ground hugging Ferraris, man buns and cappuccinos on the Left Coast. Texas is the land of, by God, four-wheel-drive pickup trucks, cowgirls and boiled black coffee at dawn. Texas is lone star, lone cowboy, self-reliance on the hoof. Well, except for the part where they hunt deer over corn feeders. In that way they’re like Californians. Except Californians bait with more style. They bait with wine grapes.

“There’s a bunch,” my guide announced. And he didn’t mean the grapes drooping from the shamrock-green vines. After stepping into the 276th alley of the day, Ryan Newkirk had spotted our four-legged quarry. Brad Fenson and I leaned in, peered over Ryan’s shoulder, and glassed a decoration of deer in the ten-foot gap between rows of cabernet grapes. Blacktails. A fawn, a spike, a forkhorn looking clueless and wide antlers protruding from behind and around the sides of the forky.

“There’s a bunch,” my guide announced. And he didn’t mean the grapes drooping from the shamrock-green vines. After stepping into the 276th alley of the day, Ryan Newkirk had spotted our four-legged quarry. Brad Fenson and I leaned in, peered over Ryan’s shoulder, and glassed a decoration of deer in the ten-foot gap between rows of cabernet grapes. Blacktails. A fawn, a spike, a forkhorn looking clueless and wide antlers protruding from behind and around the sides of the forky.

“There’s a bigger buck in there,” I said. “Bedded in the back. See the antlers?” None of the deer moved.

“Two hundred sixty three yards. Make that shot?” Our host asked.

“From what I can see in this scope, I’d have to shoot under the belly of that fawn to reach the big buck,” Brad Fenson answered. “Rather get closer. And a better angle.” Brad had drawn the long straw for this 2-on-1 hunt. Rights of first refusal.

“From what I can see in this scope, I’d have to shoot under the belly of that fawn to reach the big buck,” Brad Fenson answered. “Rather get closer. And a better angle.” Brad had drawn the long straw for this 2-on-1 hunt. Rights of first refusal.

“Doesn’t appear he’s going to give us a shot,” Ryan said. How about let’s circle this block and come in from the back. Over that rise. Should have a 200-yard shot or less.” At that, Ryan, a sixth-generation member of the family that has been farming and hunting this part of central California since the late 1800s, simply walked away from what might have been the largest blacktail buck Brad had ever seen.

“Doesn’t appear he’s going to give us a shot,” Ryan said. How about let’s circle this block and come in from the back. Over that rise. Should have a 200-yard shot or less.” At that, Ryan, a sixth-generation member of the family that has been farming and hunting this part of central California since the late 1800s, simply walked away from what might have been the largest blacktail buck Brad had ever seen.

Blacktail hunting in California vineyards is an uncommon pursuit because California vineyard blacktails are an uncommon animal. Vintners chase them out, shoot them out, fence them out. It wouldn’t surprise me if a few even poisoned them out, as they routinely do to the ground squirrels that would otherwise ravish the grapes. This assures anti-hunters and animal rights activists sufficient wine to sip at save-the-animals fundraisers.

“We tolerate the deer because Grandpa Howie and I love to hunt,” Ryan explained when I asked about the many leafless vines at Steinbeck Vineyards. “They go for the young leaves at the ends. Over the years, through trial and error, we’ve learned what level of damage we can tolerate without seriously impacting production. We hunt just enough deer each year to keep that balance of grapes and deer.” Stein-bucks at Steinbecks.

“We tolerate the deer because Grandpa Howie and I love to hunt,” Ryan explained when I asked about the many leafless vines at Steinbeck Vineyards. “They go for the young leaves at the ends. Over the years, through trial and error, we’ve learned what level of damage we can tolerate without seriously impacting production. We hunt just enough deer each year to keep that balance of grapes and deer.” Stein-bucks at Steinbecks.

“There they are,” Fenson whispered after we’d tiptoed down a cloistered alley to the hilltop overlooking the deer we’d left earlier. “Looks like the same bunch.”

“Yes. There’s that big buck. Get set.”

Brad leaned into a standing tripod, saw too many grape leaves, stepped left, and sat. Ryan put his fingers in his ears. The deer stepped through a row. Gone.

“Leaves in the way at first,” Brad explained when we got back to the truck where Linda Powell and Brady Speth waited. “Then when I sat to clear them, a doe stepped behind him. Couldn’t risk that. Then two steps and he was behind the row.”

“Leaves in the way at first,” Brad explained when we got back to the truck where Linda Powell and Brady Speth waited. “Then when I sat to clear them, a doe stepped behind him. Couldn’t risk that. Then two steps and he was behind the row.”

“And so it goes,” Linda chuckled. She’d done this hunt the year before. As PR director for Mossberg Firearms, Ms. Powell seeks unusual hunting adventures on which to test that firm’s guns. Vineyard blacktails? Pretty unusual. And at Steinbeck it’s by invitation only. Linda had teamed up with Brady, president of Riton optics, who, of course, provided the scopes and binoculars. The test guns were bolt-actions, mine a walnut-and-blued Patriot Revere in 6.5 Creedmoor with classic lines and an exceptionally figured Claro walnut stock. My under-30 friends mock it as a “Grandpa gun.” I’ve carried it like a badge of honor from the Pacific coast of North American to the Mediterranean coast of Spain, from the Rocky Mountain foothills of Alberta to the windy plains of Kansas. It’s reached game as distant as 350 yards and hasn’t missed yet.

Brad was shooting the antidote to Grandpa’s gun. An MVP Long Range in 308 Winchester with many of today’s bells and whistles such as an adjustable comb, extended drop box magazine, fluted barrel threaded for suppressor and a green synthetic stock with broad, benchrest-style forend and a butt stock only a kid —and Brad — could find attractive. But Brad is such a genuinely nice guy that we’ll forgive him. Based on his cooking skills alone, he’s welcome to hunt from my camps. With an atlatl or AR-15 if he wants.

Brad was shooting the antidote to Grandpa’s gun. An MVP Long Range in 308 Winchester with many of today’s bells and whistles such as an adjustable comb, extended drop box magazine, fluted barrel threaded for suppressor and a green synthetic stock with broad, benchrest-style forend and a butt stock only a kid —and Brad — could find attractive. But Brad is such a genuinely nice guy that we’ll forgive him. Based on his cooking skills alone, he’s welcome to hunt from my camps. With an atlatl or AR-15 if he wants.

“You go first today,” Brad insisted our second morning out. “I turned down three or four good bucks yesterday.”

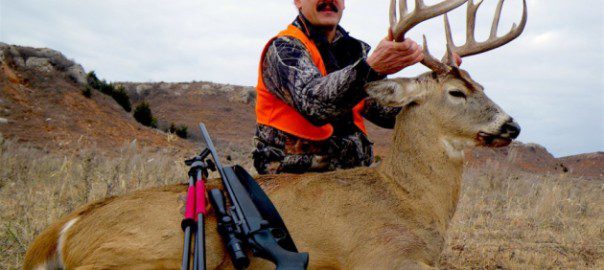

I didn’t argue. Nor did I hesitate when we spotted a good buck lying in a row of shiraz vines drooping with fruit. Ryan and I slipped over a few rows, closed the gap, eased across and rediscovered the buck in the clear, looking surprised. Neither I nor the 127-grain Barnes LRX bullet I was throwing hesitated. When the Riton reticle crossed the sticking place, the little 6.5mm barked and the handsome buck collapsed.

“Cheers! Here’s to Steinbeck Vineyards, Ryan, Mossberg and Riton,” I toasted at lunch. “Did I forget anyone?”

“The grapes,” Brady added. “Here’s to shiraz.” It is a Steinbeck tradition to open a bottle made from the variety of vine in which the deer was taken and toast it. “I wonder if he’ll taste like shiraz?” someone asked. He didn’t, but that blacktail was some of the most delectable venison my wife and I have ever enjoyed. And we’ve been eating steaks, roasts and burgers from every species of deer in North American and several from Europe and Asia for half a century. Betsy and I both rank blacktails — at least Steinbeck Vineyard blacktails — in the top three.

“The grapes,” Brady added. “Here’s to shiraz.” It is a Steinbeck tradition to open a bottle made from the variety of vine in which the deer was taken and toast it. “I wonder if he’ll taste like shiraz?” someone asked. He didn’t, but that blacktail was some of the most delectable venison my wife and I have ever enjoyed. And we’ve been eating steaks, roasts and burgers from every species of deer in North American and several from Europe and Asia for half a century. Betsy and I both rank blacktails — at least Steinbeck Vineyard blacktails — in the top three.

In some respects, Steinbeck blacktail hunting in late August is like Dakota cornfield whitetail hunting in early October. You glass the rows, spot a buck, then stalk in for the shot. The rolling landscape helps by elevating you above some rows or elevating the rows above you. Either way, you can see more of the open rows between the vines. But you still miss a lot of deer. They manage to blend into the cover surprisingly well when standing or bedded next to the trunks and support posts. Dakota deer can disappear with a leap. Steinbeck deer disappear with a dip. They duck under the wires supporting the vines. You imagine you can duck across to relocate them, but you almost never do. A buck might show up hours later a half-mile away. Brad’s did.

In some respects, Steinbeck blacktail hunting in late August is like Dakota cornfield whitetail hunting in early October. You glass the rows, spot a buck, then stalk in for the shot. The rolling landscape helps by elevating you above some rows or elevating the rows above you. Either way, you can see more of the open rows between the vines. But you still miss a lot of deer. They manage to blend into the cover surprisingly well when standing or bedded next to the trunks and support posts. Dakota deer can disappear with a leap. Steinbeck deer disappear with a dip. They duck under the wires supporting the vines. You imagine you can duck across to relocate them, but you almost never do. A buck might show up hours later a half-mile away. Brad’s did.

It was our third day and my partner was still fixated on the big buck he’d seen the first day. He and Ryan had spotted the deer, a wide 3×4, eating, of all things, grape leaves in a row of cabernet sauvignon vines. The two got the wind in their favor, sneaked out, crossed the final row and caught the buck standing north to south with its antlers in the leaves. Brad kneeled and aimed. And waited. The buck turned and looked over its back. You could have hit him with a brick. In the butt.

“That’s all he’d give me,” Brad admitted. “I wasn’t about to take a ‘Texas heart shot’ and ruin the roasts on that guy. The butt disappeared through the row and, when we ducked in — we saw the row, the whole row and nothing but the row.”

On the last day we went back to the cabernet block of the first day’s near miss hoping to strike California gold again. We found more empty rows. But then Brad cast his 10X Ritons toward a far, far hill, a corner of the farm we hadn’t explored. And there was a deer. Just one. But a buck. A good buck. Possibly THE buck.

On the last day we went back to the cabernet block of the first day’s near miss hoping to strike California gold again. We found more empty rows. But then Brad cast his 10X Ritons toward a far, far hill, a corner of the farm we hadn’t explored. And there was a deer. Just one. But a buck. A good buck. Possibly THE buck.

Yes, it was THE buck. After we’d closed to 300 yards or so, Ryan spotted him. “That’s the one. He’s coming!” Ryan said. “Get set up. Hurry. Not coming closer, but walking across the rows like he’s on a mission. I can just see a part of him. Three rows over now. Now two.”

Yes, it was THE buck. After we’d closed to 300 yards or so, Ryan spotted him. “That’s the one. He’s coming!” Ryan said. “Get set up. Hurry. Not coming closer, but walking across the rows like he’s on a mission. I can just see a part of him. Three rows over now. Now two.”

Brad was sitting, rifle in the tripod once again, solid. “Range reads 282 yards,” I reported. And then the buck stepped into the row. The rifle boomed, the dust flew and the buck fell dead.

“He stopped and the reticle was on his shoulder, so I figured why wait.”

“He stopped and the reticle was on his shoulder, so I figured why wait.”

Good figuring, Brad. Neither you nor I have anything to wine about.

There’s something about the deer-hunting experience, indefinable yet undeniable, which lends itself to the telling of exciting tales. This book offers abundant examples of the manner in which the quest for whitetails extends beyond the field to the comfort of the fireside. It includes more than 40 sagas which stir the soul, tickle the funny bone, or transport the reader to scenes of grandeur and moments of glory.

There’s something about the deer-hunting experience, indefinable yet undeniable, which lends itself to the telling of exciting tales. This book offers abundant examples of the manner in which the quest for whitetails extends beyond the field to the comfort of the fireside. It includes more than 40 sagas which stir the soul, tickle the funny bone, or transport the reader to scenes of grandeur and moments of glory.

On these pages is a stellar lineup featuring some of the greatest names in American sporting letters. There’s Nobel and Pulitzer prize-winning William Faulkner, the incomparable Robert Ruark in company with his “Old Man,” Archibald Rutledge, perhaps our most prolific teller of whitetail tales, genial Gene Hill, legendary Jack O’Connor,Gordon MacQuarrie and many others. Buy Now