As I stood near the ruin with the ruddy light of the low sun suffusing all the forest and tenderly lighting the vast delta beyond the river, I heard the chiming of a pack of hounds in the pinelands to the west. As otherwise the world was very still, I could follow the direction of their running and soon felt sure that the deer they were after was headed for the river; indeed, it was likely that he would pass near me, for I was on a famous deer crossing. To the clamor of the approaching pack was added the ominous report of a gun. Someone had shot at the deer, but as the wild music of the pack continued, I knew that the hunter probably had been unlucky.

With summer waning into the deeper and surer loveliness of autumn; with the wide peace of beauty’s fulfillment upon the world; with limpid lights resting on forest and river and lone reedland, the tumult of the hounds seemed an impertinence. They were breaking in on the solemn pageantry of a season. They were the objective, forever intruding upon the mystery and the magic of the subjective.

While they were still perhaps a half-mile away and coming straight for me, I heard a telltale crashing in the jasmine-smothered sweet-bay thicket just west of the ruins. The fugitive deer was coming. If it was a buck, he surely would swim the river, affording me a rare opportunity to watch a fine performance. As there was no wind, if I stood motionless he might pass within a few yards of me without ever detecting me. It is a thrilling thing thus to have a great, wild creature of the forest become, as it were, suddenly intimate and familiar.

Out of a blossomy thicket, his head laid back far on his ample shoulders so that the jasmine and supplejack vines slid off his mighty antlers, running as if life were in his stride and death only a heartbeat behind, there suddenly burst upon my sight the great Black-horn Buck, a creature so remarkable, so romantic, that I think it well worthwhile to attempt to record his history. To me, he has always been far more fascinating than many human beings. He is not simply a wild deer; he is a distinct personality, a veteran of many dramatic escapes, a wily old champion whose whole life has been one long series of master stratagems.

Full into sight he now burst, running wildly, yet for all his speed with a continence of flight—planned and purposeful. With a woodland fugitive, the great end is not alone to escape, but in doing so to avoid possible enemies in front as well as certain foes behind. His mighty yet graceful bulk, the ponderous grace of his movements, the heavy yet patrician elegance that such a primeval creature always possesses—all these impressed me. But what surprised me most was the size of his horns and their strange color. A 12-pointer he was, with a huge rack of burly antlers, symmetrical and wide. I knew their spread must be at least two feet. Most whitetail stags have chestnut or ivory-colored antlers, and some are gray, some almost white. But these horns were as ebony as those of a waterbuck or an ibex. Antlers of that sort make a deer easy to identify.

Moreover, there was something superbly regal about his whole makeup, a gallant superiority that marked him as king of the wildwoods from which he was now being mercilessly driven.

On his grand rush for the river he passed me so closely that I saw what I hoped I would not; he was sorely wounded. The white froth at his mouth was tinged pink, and blood streamed down his front shoulder. Had the friendly river not been so near, the pack might have overhauled him.

With the undulant gait characteristic of a deer, he sped toward the Santee. To me, he seemed too badly wounded to swim that wide expanse of water. But he never hesitated. He knew what lay beyond for him: mazy reedlands in which hounds are easily baffled, lush beds of wampee, a green wilderness of young canes, sunny ridges in the delta woods to which no enemy would ever penetrate. Life lay beyond the river after rest and recuperation, and more years in which to roam his beloved pinelands and in the deep of night to mate with the timid, shadowy does.

After all, the decision he had to make was simple; he was merely choosing between life and death. And that decision he made while yet in full flight. I saw him flee under the weeping boughs of a mighty live oak and thence across a sandy space immediately before the river bluff. As nicely as a champion hurdler times his stride, the great stag reached the 10-foot bluff ready for a take-off. There was no pause; there was no time to pause. High into the air and thence down into the river he launched himself, landing a full 20 feet from the shore. He struck with great force, but apparently he was uninjured, for immediately he began to swim.

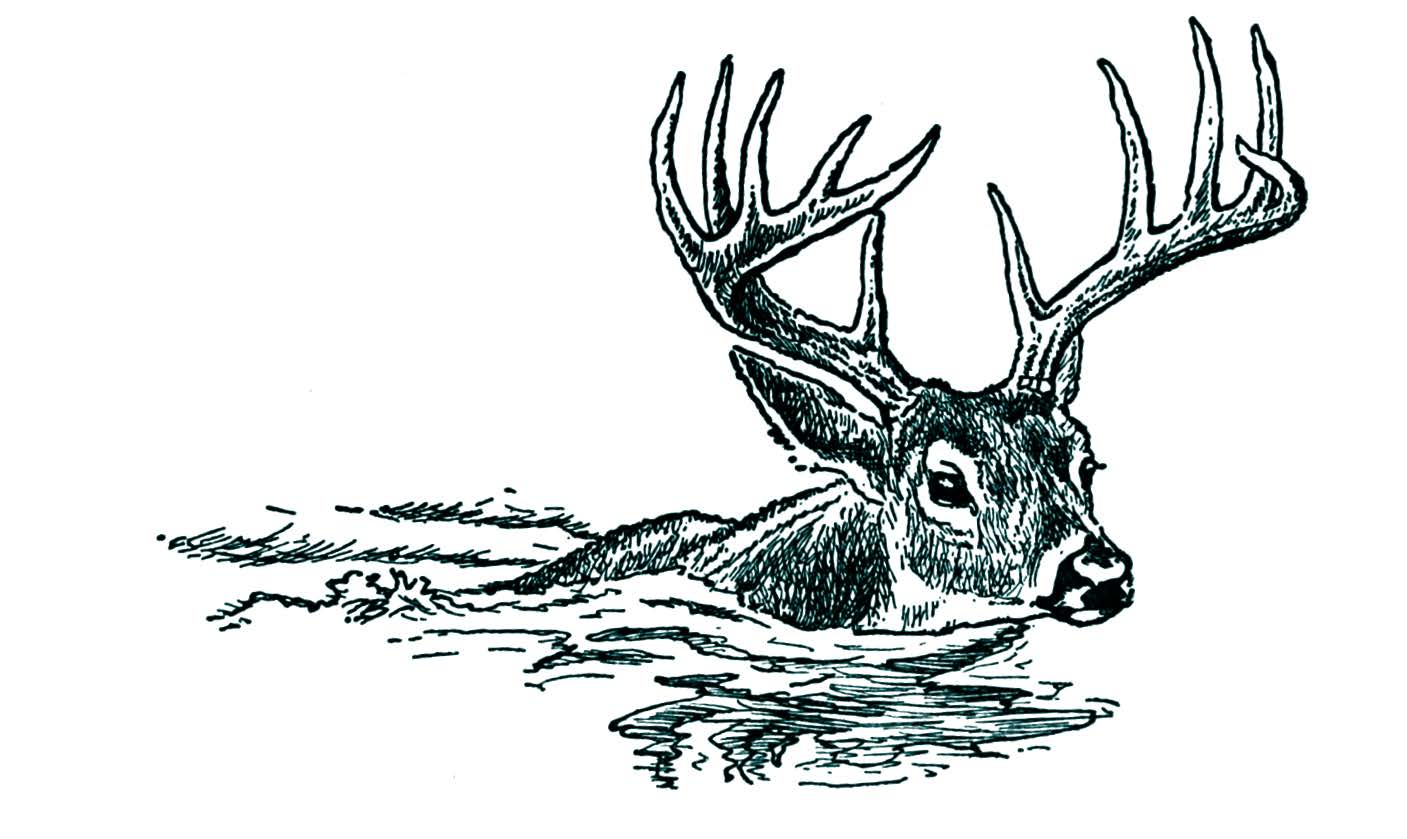

In swimming, a deer carries his head very high and nothing else of him is visible. Running down to the bank, I was afforded a perfect view of this magnificent wild creature’s gallant escape. Though he had seemed to be wounded severely, he now gave no evidence of disability. The tide was flowing out strongly, and though he had more than 300 yards to go, he never wavered and swam straight across.

With the river for a background, his great crown of dark antlers seemed larger and wider than ever. To wear such masterly horns a deer must be in his physical prime, which comes when he is from seven to ten years old. As he declines from his zenith of reproductive power, of which his antlers are the emblem, his horns become steadily smaller and more irregular.

When he was halfway across the river—safe from hunters, I knew, and almost safe from hounds that might attempt to follow him into the mazy wilderness of the delta—I heard the following pack suddenly clamor loudly behind me. Seizing a heavy stick, I turned to face the oncoming dogs, assuming a sternness of demeanor that was intended to show that the fugitive buck was my private property. Now, even when a hound is wild on a hot and bloody trail, he does not like to encounter a strange man, especially if the stranger brandishes a club and shouts dire imprecations.

When the hounds saw me and the mood I was apparently in, they utterly lost their enthusiasm for the chase; in fact, they were comically human in pretending that they weren’t after a deer at all but had merely happened along. In embarrassed silence they vanished into the woods whence they had come. Looking again across the river, I saw the Black-horn Buck climbing the farther bank in safety. Soon he was lost to sight in the lush greenery of the canes and marsh that fringe that sanctuary.

It would seem that when a deer has been so desperately chased out of a certain haunt and wounded besides, he would stay away from it. But it is not so. Every wild deer has a definite range, usually quite limited in area, and to this he clings with nostalgic devotion. If undisturbed and if food is sufficient, a deer will range over the same few acres year after year. Nor does he go from place to place in haphazard fashion. He follows definite routes, and his ancestors have followed those same trails (sometimes defined and sometimes not) as long as we have records of deer hunting in this country. I know many deer crossings that were named before the Revolution, and those are favorite runs for deer today. Often the woods have changed utterly, and the very landmarks in the woods that gave these crossings their picturesque names have vanished. But deer still travel the same courses.

There is no sign of an oak at the Crippled Oak Stand, and the giant yellow pines have gone from the Seven Sisters Stand, but the deer still infallibly run to the Crippled Oak and to the Seven Sisters.

If driven from his favorite range, a deer will always return. He may be deliberate about it, but he will come back. For he loves no place on earth as he does his native heath. He prefers to live and to die at home. When I saw the Black-horn Buck swim the Santee, I knew that he would return.

On my return to the plantation, I began to ask the Negroes about the Black-horn Buck. Why was it that they had not told me of the presence in our home woods of so remarkable a creature?

To my surprise, they knew all about him, but they did not consider him a deer. He was a token—that is, so different and so superior was he that he was a supernatural presence. They were not inclined to talk much about him. Had not Steve’s Bess died only a week after she had seen him calmly cropping peas in the field on the edge of the Negro graveyard? And in the same month in which Paris Green had seen him, lightning had struck Paris’ cabin. They hinted darkly that it would be as well if I took no especial interest in this remarkable creature.

About a month later, when I was sitting one morning on my front porch in the balmy winter sunshine of those kindly latitudes, I was startled to hear a mortal cry of fear and agony from the kitchen behind the house. As I knew that no one was in the yard save Ogeechee, a Negro who had long suffered from consumption, I was afraid that a fatal hemorrhage had overcome him. But as I started up, a great form rushed past the house and, with desperate yet stately speed, tore down the sandy road toward the woods, jumped the tall gate and was lost in the forest.

Hurrying to the back of the house, I found Ogeechee sitting in the sun on the kitchen steps, tears streaming down his face.

“Did the buck scare you?” I asked.

“I have done seen my token,” he answered solemnly, and all my attempts to make light of the matter were in vain.

The stag had swum the river behind the house, walked up the pathway and must have been within four or five yards of Ogeechee before either was aware of the presence of the other. To the deer, Ogeechee was just another man; to the Negro, the Black-horn Buck was an apparition, sent to summon him to worlds other than ours. Two weeks after that, I read the funeral service over poor Ogeechee.

It came as no surprise that the fame of the stag increased among the plantation Negroes, and his uncanny ability to escape white hunters contributed to the superstition of his magic power. To me, it seemed only an illustration of the truth that certain beasts are genuinely distinguished. There are distinct individuals in nature, creatures whose unconventional behavior is the proof of their high intelligence. Most of them are superb solitaires. Now and then we encounter complete originals so informal and arbitrary in their deep sagacity that the mere novelty of them is refreshing. And the Black-horn Buck is of this type.

One of my plantation Negroes, less sensitive to the occult than the rest, told me that he had three times, while working the turpentine woods in the dewy hour of daybreak, seen this wily champion “going to bed.” He reported that on each occasion the deer had waded across a pond before lying down for the day. A deer is well aware that some of his enemies trail him, and he knows that water has the effect of laying the telltale scent. Yet only the wariest stag will habitually practice this safeguarding maneuver.

One morning, I ran my car into a little blind road off the plantation highway and stopped it there, intending to look at some timber. As I stepped into a low, copse-like growth of gallberry and sweet-bay bushes, two bucks and two does sprang out of the sparse cover and dashed lithely away, their long, effortless leaps made conspicuous by their tall, snowy tails held stiffly erect. I watched them for a full minute until they disappeared into a thicket of young pines. Deciding to look at their beds, I walked into the fragrant greenery.

A slight noise made me look back. There was the Black-horn Buck himself! Almost without a sound, he had eased from his couch after waiting until I had passed him. Amazed at his size and his tremendous rack, I was more astonished by his behavior, which had about it the savor of ancient wildwood magic. With a certain ponderous grace, he dashed around my car and then sped away with that obstacle between us. No alert ruffed grouse ever put a shielding hemlock between himself and a hunter with more swiftness and accuracy than the Black-horn Buck put my own car between us. He was running toward Montgomery Creek, which is affected by the tides in the river. Knowing that the tide would then be high, I wondered if he would swim across the deep estuary. I was soon to learn.

The next day, I asked Peter Small, our woodcutter, if he had seen the great stag, for I knew that Peter had been working in the woods near the mouth of the creek.

“I done heard him comin’,” he told me, “and when he done get to the water, he never stopped. He jumped right in from the old bluff, splashin’ the water as high as them young cypresses. But he didn’t swim across. No, sah, he’s too smart for that. He just swam down through the middle of the creek until he come to where it flows into the river. Then he got out on the same side he had left. A hound would go crazy trying to follow that thing,” Peter added darkly.

“Would you follow him?” I asked casually but designedly to discover the degree of his superstition.

“Cap’n,” he responded soberly, “some things ain’t meant to be followed.”

The fame of the Black-horn Buck had all the hunters of our plantation region deeply stirred. Nearly all of them had seen him and many of them had shot at him, but still he lived. If hotly pursued, he would swim the river, but always he would return to his beloved haunts.

One twilight, a solitary hunter attempted to waylay him by waiting on the high bluff of the Santee at Fairfield. Some other hunters had roused him on the delta, and it was altogether likely that he would cross the river at this point to regain his home on the mainland.

On the lofty bank the sportsman waited; and his vigil was rewarded when he saw a great crown of ebony antlers moving above the yellow tide beneath him. Because of the conformation of the bluff, upon coming ashore the old stag would be obliged to take a single bypath into the pinelands. The hunter crept to a stand within easy distance of this trail. But along its dusky privacy, the Black-horn Buck never appeared. Darkness fell and the hunter abandoned his quest, half-convinced that the Negroes were right in their estimate of the nature of this remarkable deer.

When he investigated next morning, he discovered that the wary buck, after reaching shore and most likely detecting the hunter by scent, had climbed straight up the bank for about 20 feet and had there craftily couched himself in a mass of wild honeysuckle vines.

With enemies behind him and an enemy in front, he had secreted himself where even his most inveterate intelligent foe would never think of looking for him. He saved his life by a shadowy subterfuge as unique as it was effective.

Not very long after that, I was again mending a fence and had in my hands only a hammer and some nails. I noticed in a low copse, not 30 yards from me, the massive crown of the king of the woodland. So close was I that I could see him sedulously watching me.

Not wishing to disturb him, I turned back toward the house where, sadly, I met a hunter. Foolishly, I told him what I had just seen, but added that I did not want my visitor disturbed. Unknown to me, the hunter stole out along the fence to stalk the stag. Crestfallen, he came back.

“I thought you said that buck was tame?” he protested. “Didn’t you say you walked within thirty yards of him? He got up from me when I was two hundred yards away.”

“A buck like that,” I reminded him, “knows the difference between a hammer and a gun.”

It is now many years since I first became acquainted with the Black-horn Buck. Still, he roams my plantation woods and in the summer helps himself to my peas and corn. Still, the Negroes fear him; and still, I am privileged to love and admire him, for he has taught me that the natural world can develop a great personality. Now, whenever a hunting season passes without proving disastrous to him, I rejoice that his magnificent ebony crown is not drying out at some taxidermist’s shop, but is thrusting aside dewy pine boughs in the moonlight or, deep in a fragrant bed of ferns and sweet bay, is affording the shy moonbeams something really mystic on which to sparkle.

Illustrations By Paul Bransom

On these pages is a stellar lineup featuring some of the greatest names in American sporting letters. There’s Nobel and Pulitzer prize-winning William Faulkner, the incomparable Robert Ruark in company with his “Old Man,” Archibald Rutledge, perhaps our most prolific teller of whitetail tales, genial Gene Hill, legendary Jack O’Connor,Gordon MacQuarrie and many others.

On these pages is a stellar lineup featuring some of the greatest names in American sporting letters. There’s Nobel and Pulitzer prize-winning William Faulkner, the incomparable Robert Ruark in company with his “Old Man,” Archibald Rutledge, perhaps our most prolific teller of whitetail tales, genial Gene Hill, legendary Jack O’Connor,Gordon MacQuarrie and many others.

This is an anthology to sample and savor, perhaps one story at a time or in an extended session of armchair adventure. That’s a choice for each individual reader, but rest assured that on these 465 pages, there’s an abundance of opportunity to be enlightened and entertained. Shop Now