I was deep in the heart of northern Minnesota – the Big Empty. The Homestead Act gave this land to any person desperate enough to take it, reckless enough to hack away the underbrush, notch together a cabin, plant a few potatoes, attempt to stave off starvation, hypothermia and madness for the next five years. Land-hungry Scandinavians came in droves. Very few of them made it.

The woods took over. The sodden cabins slowly sank back into the earth, a few pitiful artifacts – a washbasin, a plow, perhaps a gasoline-powered Maytag – rusting in the sumac, thistle and prickly ash at the edge of vanishing clearings. Taxes mounted. County governments, reeling from the loss of population and revenue, reluctantly took title. Today, the Big Empty is an astounding nine million acres of tax forfeiture state and Federal forest – bigger than Vermont and New Hampshire combined. It’s home to scattered bands of Ojibwe, perennially mortgaged loggers, a few hardscrabble farmers, out-of-work miners, and the realm of moose, wolves and bear.

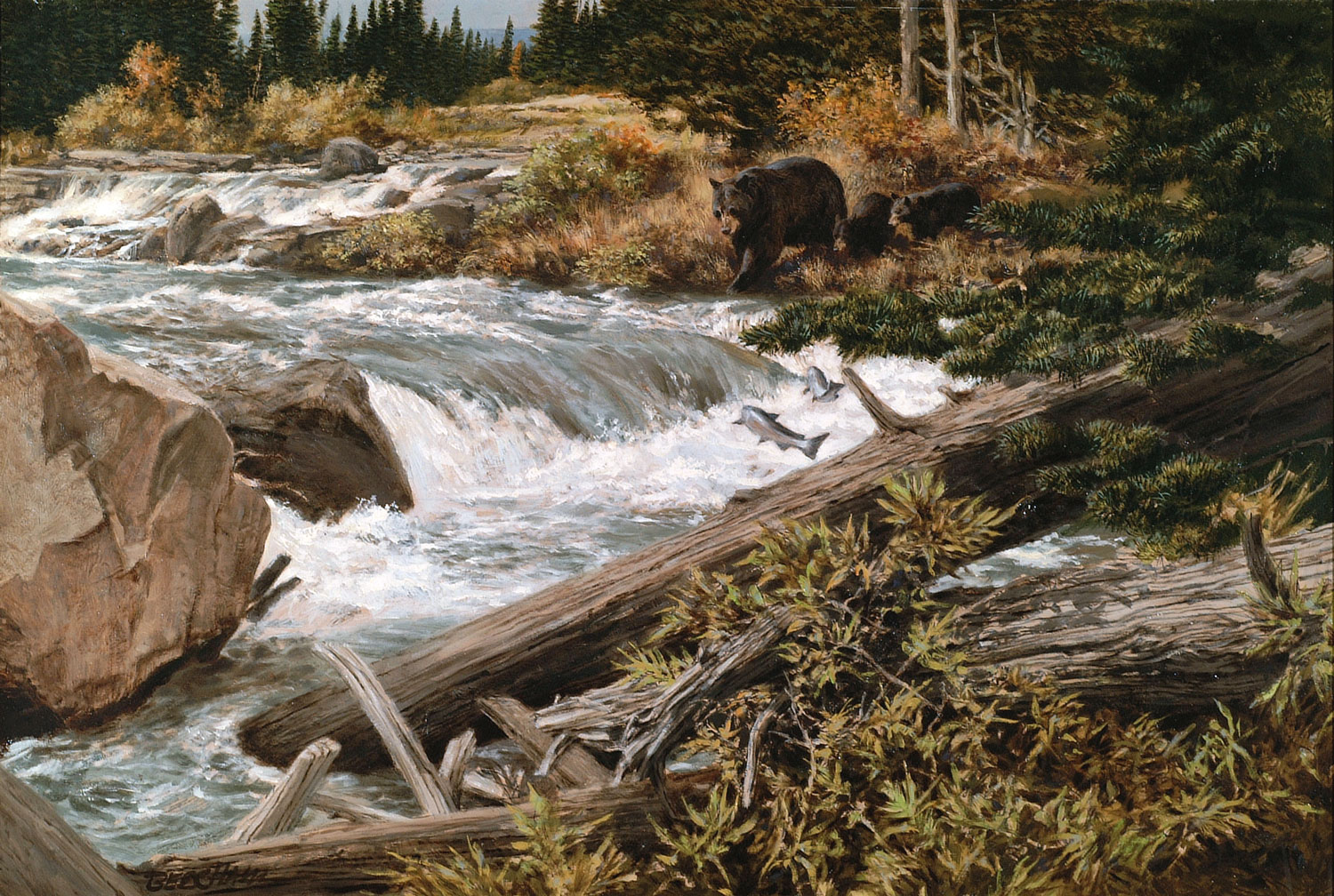

Drawn by hunger or curiosity, black bears have been known to approach surprisingly close to humans, who only rarely become aware of their presence. Bears that have lost their fear of man are the most dangerous.

The black bear, Ursus americanus. Nobody knows how many there are in Minnesota. Even the Department of Natural Resources doesn’t trust its own estimates of 18,000. Each year they further liberalize regulations, increase permits, and each fall complaints of raids on apiary, field and feedlot skyrocket as bruins go into a frenzy of wild feeding as they build fat reserves for their long winter’s sleep.

Minnesota is one of a handful of states that allows bear to be taken over baits – a major concession considering the inaccessibility of the terrain, the impassibility of north- country brush, the nocturnal nature of bears. I was feeding 300 pounds of meat scraps each week at three locations – all of it struggled into the brush in five-gallon pails, covered with logs too heavy for badger, coyote, wolf. And each time I ventured into those dark and brooding evergreens I found the meat gone, ground churned up, bark literally scratched and licked off surrounding trees. After carefully reading the tracks, claw- and tooth-marks, I selected my hunting site, a bait on a long low aspen ridge, studded with glacial boulders, spiked with spruce and red pine.

I had induced Judi to come along on opening day. Judi is a nurse, a paramedic, and carries a “scratch bag” with necessary supplies to glue a man back together should he have a serious discussion in bear braille. She is also fine company and is pretty level-headed in a tight spot, a prime consideration when choosing a partner for the bear woods. Judi drove the pickup down the logging trail, dropped me off as close to the bait as geography allowed, then took the truck a half-mile back down the track, parked in shade and got out a book as the northern sun began its long western slide.

I sat a dozen feet up a large red pine, perched on a portable ladder stand that disconcertingly bore the signs of recent occupation by a bear. The carpet meant to quiet my nervous feet had been peeled from one corner, the foam padding gnawed and frayed. I was hanging a lot of trust on my rifle, a 7×57 custom DWM Brazilian Mauser loaded with five, 175-grain round-nose slugs, slugs not likely to be deflected by intervening brush or stopped by muscle and heavy bone.

The wind, still hot from the distant prairie and bearing just a hint of dusty harvest, rushed through the treetops, twisting and whistling through the evergreens, rattling the aspen. I waited, watching the trails that led to the bait like the spokes of a wheel, paying special attention to those angling in from behind my gun shoulder, the direction dreaded by all hunters of dangerous game.

The red squirrels told me he was coming. I heard the first I one off to my left, chattering, clicking, cursing, then another behind me, yet another to my right as the bear cautiously circled before making his final approach.

The old Ojibwe consider the bear a spirit rather than flesh and bone. Little wonder. After a dozen seasons in the bear woods, I have yet to see one approach a bait. They appear silently and mysteriously, as if coalescing out of earth, water and air. As it was, I was checking the trail behind me. I glanced back at the bait and there he was: powerful, black, beautiful, just starting to rake the first pawful of bait from beneath the logpile. My little Mauser pointed like a fine English double. In a flash I had the crosshairs six inches behind his shoulder blade.

Judi heard the shot and immediately walked over to get me. After stripping off extraneous gear and my stifling camo jacket, I gave her the rifle, strapped on my .357 Blackhawk, got the flashlight, began following blood. There was not much to follow – a drop hanging on the edge of a leaf, a dark splash on darker earth, the faintest smear on a sapling. We found the bear, as the Ojibwe say, in the fullness of time. He was most inconveniently located, but we untangled him from the brushpile, dragged him to dry ground, did our field dressing.

That lightened our load somewhat, but pulling him up- and-over all the fallen spruce was back-breaking work, because he kept snagging on their broken branches.

“One, two, three, PULL,” we chanted, three feet at a time, until – about nine o’clock – sweating and winded, we found ourselves back at the bait, only 300 yards from the truck.

We had no sooner begun the last leg of our ordeal when Judi said, “Roger, there’s a bear behind me.” Then she quickly repositioned herself and modified her statement: “Roger, there’s a bear behind you!”

Up to this point, at least, it was a normal Minnesota bear hunt. A three-hour track and drag, even stepping on another bear or two in the process – all these things are to be expected. However, most casually encountered bears realize that further approach could be hazardous to all parties, and they promptly vacate the area with much snorting, woofing and breaking of brush. But this one violated all accepted etiquette-advancing, growling, snapping, slapping the ground, making kindling of surrounding saplings.

At this point, two small details began to loom large. First, our flashlight had begun to falter, and second, after several times having been confronted with the business end of my rifle while it was slung from Judi’s shoulder, I had unloaded it and left it propped against a tree, planning to retrieve it after we had dragged our burden through a particularly tough spot.

We faced down the bear’s advance with the flashlight – such as it was – and my .357, which I was now wishing was a .44. “We need to get the rifle,” I said, with as much confidence as I could muster.

We took three steps toward it, then stopped.

The bear was advancing closer. I pointed the yellowing beam in his direction, and he stopped, snarling, and began breaking more brush. I saw a hint of black moving in black, the reflective glimmer of eyes.

Judi: “Dammit, I can’t see!” The light went back and forth in rapid succession, like I was attempting to flag a passing freight.

The bear covered more ground. I gave Judi a handful of cartridges, and she put one in the chamber; clack, clack, the wonderful authority of a Mauser lock-up.

Though Karamojo Bell had reportedly laid low many elephants with the little 7X57, I considered the bear in possession of all the cards. He could see us; we couldn’t see him. He possibly outweighed the two of us combined, had longer claws and teeth.

“Can you see the crosshairs?” I asked. Judi looked through the scope, gulped, nodded. “Put them right between his eyes, let him have it if I give the word.”

The bear slapped the ground again.

Judi said, “He wants the bait. We’re in the way.”

I said, “We’re in the middle of ten-thousand acres of woods. He’s got all the room he needs.”

Having said that, I made an adrenaline-assisted assessment. The troublesome bear was a creature of habit. He usually arrived second at the bait, sent the first bear packing. Now he smelled his rival, plus blood. Human scent all over the bait, while annoying, had already proved itself to be no serious impediment.

Clearly, he was in need of some schooling.

I stamped, spoke loudly. “Hey, there’re people here, dummy!” There was a non-committal, throaty rumble, a nasal whine, more breaking brush.

Being totally uncomfortable in our present predicament, I was not willing to endure it forever. And I surely was not going to give up my kill. I was ready to escalate the confrontation, if that’s what it took to get to the truck. I hauled the Ruger back to full cock. “Hey, you, come on, show yourself!” The bushes moved. I sent a warning shot chasing through the brush, right above where I judged him to be. The Ruger bellowed and bucked in my hands.

Now, did the bear finally get the picture, did he take off after encountering a thunderclap of muzzle blast, its flash the size of a jack-o-lantern?

Guess again.

Judi said, “You’re a better shot than me. Let’s change guns.” Her voice was shaking.

We exchanged guns – weapons.

I said, “if he rushes us, I’ll shoot once, then go down, get the rifle over my throat. You shoot when he gets to me. You’ll only get one shot, so damn it, shoot straight. Right into the top of his head.”

She gulped again and said, “Hope I get a bullet into the bear and not the jackass.”

I begrudgingly accepted her judgement, then made myself another promise – the same one i had made every time I had found myself in a tight spot in the bear woods. “If we get out of here in one piece, this will be my last bear hunt.”

Judi, even under the duress of the moment, knew better. “Huh,” she said.

The bushes began moving as the bear sidestepped the trail, worked his way around us. He was either heading for the bait, or getting better wind, steeling himself for a charge. A long stretch of dark, empty woods stood between us and the truck.

Judi said, “Let’s get the heck out of here.” Or words to that effect.

While previously we had paused after pulling on the count of three, now it was a continuous “One, two, threeeeeeeeee” all the way to the road, our load sliding like it was on Motor Honey.

There was a three-foot drop where the woods met the road. There was also a short cut-off sapling that pierced the carcass like a punji and stopped us cold. Judi lost her grip on the rope, went tumbling out into the road, all knees, elbows and flying hair.

She scrambled to her feet. I ran for the truck, dropped the tailgate, backed it up to the bank, left it running, lights on.

We worked the animal free of the sapling and slid it toward the truck, nervously eyeing the darkness, Judi whispered, “He’s back.”

Once again, we faced him down with dying candlepower, shouted threats, prayers.

We had but a single heave before we were home free, but the drag rope slipped from behind the dead bear’s head, Judi went flying again, this time landing in the back of the truck, in a clatter of bait buckets, treestands and tool boxes.

Once again she scrambled to her feet. We wrestled our load over the tailgate, slammed it. I jumped over the side, intending to pull the truck beyond the limits of a sudden charge, Judi was still in the back. “Stand right there,” I yelled, slipping the truck into gear.

“Forget it,” she said and rushed for the cab.

There was a six-pack of very cold refreshment behind the seat, swimming in the slush in my cooler, at least two cans with my name on them. There was a single cigar that I longed to have clamped between my trembling lips. But I got the truck into overdrive and did not stop until we were a full two miles down the road. Only then did I pull off the road, quench my thirst, chase the end of that shaking cigar with my Bic.

By then it was nearly midnight and we had to drive many miles to find a registration station still open that could do the paperwork required by the DNR. It was Haami’s Bar and Grill, Puposky, Minnesota, population twenty-four, in the heart of The Big Empty. Out in the parking lot was a group of disappointed hunters who gathered around our truck, marveled at my bear, popped flashbulbs.

Since I was concerned some hapless birdwatcher or berrypicker might also encounter the aggressive bear, I offered an empty-handed hunter my stand, gave him directions to it. But I extracted a solemn promise that he would call and give me a full report after his hunt.

The call came late the following Sunday night. He had seen the bear crossing the road. It was, as I had suspected, enormous. And apparently, some of my schooling had stuck. The bear had circled the bait, woofing and snorting, but had refused to show itself before the clock ran out on legal shooting time – thirty minutes after sundown. Now the acorns had fallen, my caller informed me, and the choke-cherries had fully ripened. The bear had less hazardous options. He doubted he would get a crack at him.

So I suppose that bear will be awaiting my next foray into the Big Empty…

A little smarter, a little bigger.

This article originally appeared in the 1999 March/April issue of Sporting Classics.