If immortality is nothing more, or less, than the condition of being remembered, the dogs profiled here will always remain vibrantly and brilliantly alive. These canines are, by any reckoning, the Best of Breed.

Not long ago, I had occasion to write to a man I’d never met. I knew him through his dogs — or, more to the point, through a dog, an English setter that he’d handled to a number of field trial wins in the early ’80s. By way of introduction, I mentioned in my letter that I remembered her. And part of what this man wrote in reply cuts to the very essence of the special relationship that we have with our gun dogs: “My wife and I watched her enter the world in 1976 and ushered her out seventeen years and eight months later, and every day between was a privilege. She took me places, physically and emotionally, I would never have otherwise gone, opened doors otherwise closed, and I am thankful I was allowed to share her life. Truthfully, not a day passes that I do not draw on the memory of her never-die heart and courage in one way or another.”

That’s the thing about dogs — especially the dogs with whom we join in the ancient partnership of the hunt. They give us more than we can possibly give in return, and they never really fail us. If there is a failing, it is in ourselves, and our expectations. The reason dogs touch us in ways and places that nothing else can is that their souls are free from darkness. They are pure in a way that we can never be, and honest, and their devotion is unconditional. The qualities that we take for granted in our gun dogs are the same ones that cause us to call some people heroes.

James Thurber, the humorist, got it right when he said, “If I have any beliefs about immortality, it is that certain dogs I have known will go to heaven, and very, very few persons.” And if immortality is nothing more, or less, than the condition of being remembered, the dogs profiled here will always remain vibrantly and brilliantly alive. They are, by any reckoning, the Best of Breed.

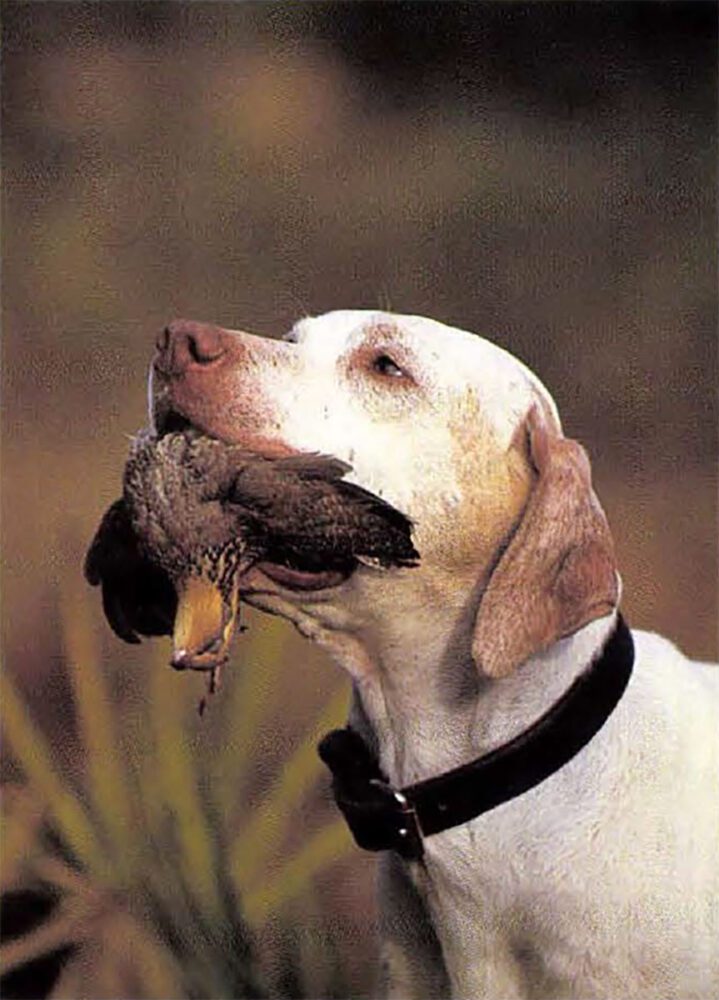

Labrador Retriever

Chocolate Lab.

Most of us who share the company of gun dogs would agree that their presence enriches our lives. They are our friends, our partners, our teachers; they are the better part of ourselves. But there are a handful of people who can take this one step further. Dr. Michael Markgraf, for example. You see, Markgraf’s Labrador retriever, Maggie, saved his life.

A dentist who makes his home in southeastern Wisconsin, Markgraf took a day off a couple Novembers ago to go duck hunting. This was nothing new for him; he was an experienced waterfowler, a man for whom there was no greater thrill than the sight of a flock of red-legged mallards, fresh from Canada, dropping into the blocks from a lowering sky As usual, Markgraf’s sole companion that morning was Maggie, his doughty yellow Lab, full-time family pet and part-time duck dog.

The weather was a duck hunter’s dream. Blinding snowsqualls and a bitter north wind greeted Markgraf when he arrived at Lake Puckaway, a favorite late-season spot in the central part of the state. There was a marshy point about a mile from the landing that he figured would be the ideal place to set up his spread. Navigating by compass in the pitch-black, pre-dawn gloom, he aimed his battered, 14 foot duck boat in that direction. Markgraf knew he should have replaced the leaky old craft long ago. But it had a lot of sentimental value – it had been his father’s — and duck hunters, more so than any other class of sportsmen, are apt to be swayed by sentiment, by tradition. Maybe he’d start shopping for a new boat come spring.

Needless to say, the ride was rough. But the old boat seemed able to handle the heavy seas, its bow plowing stubbornly through the swells. Markgraf’s first inkling of trouble came when he realized that the craft was canted at an unnatural angle. He looked around, and saw to his horror that the stern was almost completely awash. The gas tank was floating; the decoys bobbed on their anchor lines. Instinctively, Markgrafswung the tiller, turned the boat toward shore, and opened the throttle as wide as it would go. He knew he was in a dangerous situation; exactly a year earlier, on the same lake and under remarkably similar conditions, a duck boat had capsized. The dogs made it safely to shore. The hunters didn’t.

Black Lab.

Thinking of nothing except keeping the motor running, Markgraf managed to get about three-quarters of the way back before the outboard sputtered and died. Then, in a heartbeat, he found himself in the icy water, clinging to the overturned hull. Like the great majority of duck hunters, he wasn’t wearing a life jacket, and everything had happened so fast that he hadn’t been able to grab the flotation cushion he’d been sitting on. He tried to encourage Maggie, who was swimming in circles around the boat, to go to shore (and presumably summon help) by commanding” Maggie, go!” But she’d just paddle a few yards, glance over her shoulder as if to say ‘Aren’t you coming, too?,” and return.

By now, it was clear to Markgraf that he’d die of exposure if he stayed with the boat. With Maggie swimming at his side, he tried to backstroke to shore, but it was no use. He kept getting turned around, and he was losing strength rapidly. ”I’d pretty much given up,” he admits. But then he looked at Maggie, and those soulful eyes told him that she knew what was at stake. Normally, she can’t bear to have her tail touched or played with — it’s a little idiosyncrasy of hers — but when Markgraf grasped it, she understood perfectly.

“There was a lot of non-verbal communication between us,” he attests. “How do you explain to a dog, ‘I’ll grab your tail, and you’ll tow me to shore?’ All I said was, ‘Maggie, go!’ “It seemed like it took Maggie a small eternity to swim those 250 yards; it was all Markgraf could do simply to hang on and keep breathing. But then, miraculously, his feet touched something solid. They’d made it! While he waded the last few yards to shore, Maggie rolled on her back in the sand, kicking her legs in the air as if the entire ordeal had been more fun than chasing a tomcat up a tree.

Later that same morning, after standing in the shower until the hot water ran out and unwittingly scalding his nearly-frozen feet, Markgraf returned to Lake Puckaway He recovered his boat, motor, oars, decoys — even the flotation cushion that he hadn’t been able to find in the dark, roiled water. The only things Markgraf lost were his shotgun and shell box.

“It was eerie,” he says of returning to the place where, only hours before, his life had nearly been snatched away “There was nobody out there. All I could think was that it was a good thing Maggie didn’t go to shore without me. I’d say I was damn lucky, but this went beyond luck. There had to be a higher purpose at work.”

And yes, a week or so after the “incident,” Markgraf and Maggie climbed back in the saddle — in a new boat – and went duck hunting. For the Lab, it was business as usual. Despite wearing a PFD, Markgraf’s reaction was somewhat different: “I was nervous as hell.”

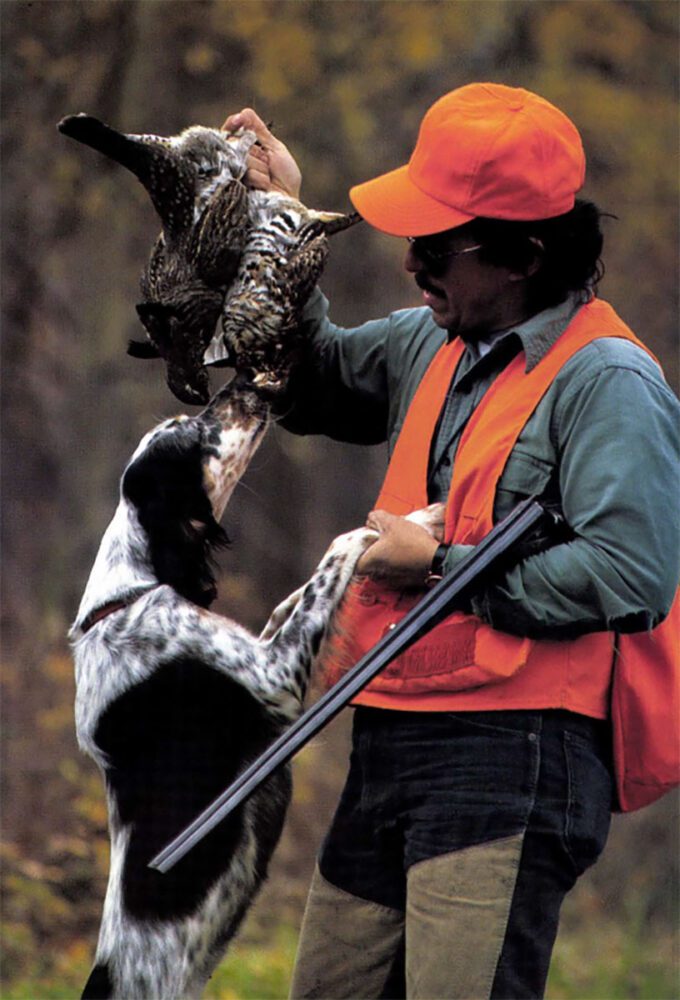

English Springer Spaniel

After all the evidence has been presented, all the testimony heard, a solid case can be made that, in terms of sheer effectiveness, the springer spaniel is the ultimate pheasant dog. This is saying a mouthful, for no gamebird is as crafty, cagey, and downright sly as a long-tailed, sharp-spurred rooster. Such a bird will test even the canniest dog to its limits — and then some — especially in a classic “rough-shooting” situation. Just ask Keith Erlandson.

If you know anything about springers, you know about Keith Erlandson and his Gwibernant Kennels in the mountainous north of Wales. The “short list” of famous dogs he’s been associated with includes Hales Smut, the greatest sire in springer history; Gwibernant Ganol, who won back-to-back U.S. National titles in 1964-65 under the whistle of Dave Lorenz; English National Champion Dinas Dewi Sele, the dog Erlandson calls “the best spaniel I ever trained, handled, or saw,” and Cortman Lane, an influential sire who captured the English National title in 1986.

The springer spaniel is an ebullient, indefatigable companion in the pheasant fields, capable of truly spectacular retrieves.

A delightful raconteur and prolific writer – he is the author of many articles, as well as the acclaimed book, Gundog Training – Erlandson has been critical of American springer breeders for their tendency to produce what he calls “field trial specialists.” And it’s a fact that, as exciting and accomplished as they are, the vast majority of field trial springers in this country have never had to match wits with a truly wild bird. Erlandson’s view is the same one expressed by William Harnden Foster in the 1930s regarding pointing dogs: that there should be no substantial difference between a working gun dog and a field trial dog, the latter merely being the former “on public display” This, of course, is the way it should be — and, for Keith Erlandson’s dogs, is the way it is. Here’s the story of the most astounding retrieve of a wounded pheasant he ever saw:

“In America, you call a winged pheasant a ‘cripple: We call it a ‘runner: which I believe is more descriptive, as a bird with just one wing gone can run like stink — and by no means always in a straight line. So, in either a hunting or afield trialing situation, the dog that excels on runners enjoys a huge advantage.

“Many years ago on a late December afternoon, I was working along the foot of my mountain. I had a young black cocker hunting the cover and the springer field champion, Gwibernant Ashley Robb, walking at heel. The cocker was doing a splendid job, and after a while flushed a cock. I sent 15/16-ounce of shot after him from my 16-gauge. He dropped like a stone at 40 yards, but fell breast first and showed nobody shock, like a bird does when hit really hard. The cocker went directly to the fall at my command, covered the area thoroughly, but failed to collect the bird.

“I called the cocker in then and sent Robb, who had held his mark. He went to the fall and immediately began to trail forward until lost from view. Some minutes later I saw him high up the mountain to my left, trailing like a foxhound but working toward me. He came lower and lower, and then I spied the cock as it crossed my front, 15 yards ahead. It saw me, too, and bored off again on exactly the same track as Robb had taken when he first caught the scent. Robb appeared in a matter of seconds, still hot on the trail, and the performance was repeated in identical fashion, with Robb coming into view high above me only to follow the cock back down the mountainside. This time, however, when the bird crossed my front it was obviously tiring. It soon tucked into cover, and Robb nailed it about 15yards downhill of where it had originally fallen.

“This was the best runner I have ever seen taken. The following week, Robb made a spectacular effort on another runner in a trial, an effort that ultimately won the event for us. But while it was a 400-yard collection, the bird had run reasonably straight, with the exception of one right-angle jink which the dog had to sort out. The bird on our home ground, on the other hand, had put up an exhibition the likes of which I had never seen before, nor have I witnessed since.”

Chesapeake Bay Retriever

What has never been in dispute about the Chesapeake Bay retriever is its ability. No breed possesses a fiercer desire to retrieve; no breed is as willing, even eager, to brave the foulest, coldest, nastiest conditions imaginable. Among a certain cadre of hard-core wildfowlers, the Chessie has always been the dog.

To many hard-core waterfowlers, the Chesapeake has always been the dog. But as field-trialers, the breed had little to brag about … until JJ’s Jessie had her day.

The general sporting public, however, tends to regard the breed with apprehension. There is no denying it: The Chessie suffers from an image problem. Unfair stereotyping has contributed to this; it is also the case that some of the same qualities for which the Chesapeake was once prized are no longer viewed as attributes. But if the breed had a few more representatives like JJ’s Jessie, its image would be solid gold.

The only Chesapeake female ever to become a Dual Champion and an Amateur Field Champion (with an obedience title thrown in for good measure), Jessie served, during her long and hugely successful competitive career, as an ambassador for her breed. “She’s a wonderful, gentle lady,” says Mitch Patterson of Addison, Illinois, who co-owns Jessie with his wife Linda, and their daughter Jennifer Jaynes. “Due to her ability, personality and, most importantly, her performances, she’s smashed a lot of the negative attitudes towards Chesapeakes. People around the country have grown to respect Jessie, as she’s done some pretty unbelievable things. One of her best ‘campfire stories’ goes like this ….

“In 1988 I was in Colorado, running Jessie in an all-breed trial. We were definite unknowns, pitting a Chesapeake against some of the finest, professionally trained and handled Labradors in the country. I felt overwhelmed as I watched the great Labs perform during the first series, a difficult triple landmark. As Jessie and I walked to the line, I could hear the typical, derisive “Peake” jokes from the gallery. Well, the birds fell, and Jessie executed her retrieves almost perfectly. She did another excellent job in the second series, a 275-yardland blind. No one in the gallery was joking now; they could see that Jessie was serious competition.

“The third series, a water blind, was the turning point of the trial. I think it also changed, for good, the way Jessie would be viewed by the field trial fraternity. Starting from the upper side of a hill, the test required that the dogs cross an angled gravel road enroute to a pond. Once in the water, the dogs would have to swim parallel to shore for 225 yards, cross two points of land, then swim past a third point where several ducks had been placed in a crate as a distraction. Jessie had always excelled at water blinds, but this was the most difficult I’d ever seen. I watched, the pressure mounting, as dog after dog failed to complete the test.

“Well, it took Jessie twelve minutes to make the retrieve, and I think I held my breath the entire time. I corrected her line once, just before she entered the water. She crossed the first two points, but as she swam toward the third, I could see that she was giving the ducks in the crate a good hard look. I swear my heart stopped, and I know my stomach was churning. But Jessie realized that she had no business messing with those crated birds. She swam past the point, found the blind, and retrieved it. I could breathe again.

“Jessie went on to win the trial — against the odds, and to the enthusiastic cheers of our fellow competitors. I guess you could say that she made converts out of them. But then, she had that effect on a lot of people who couldn’t — or wouldn’t — believe that a Chesapeake was capable of doing the things she did.”

Pointer

Magic.

The “fact” that the pointer — call it the English pointer, if you prefer — is a cold, impersonal, bird-finding machine that neither seeks nor shows affection would come as a surprise to a lot of people. And it would certainly be news to Lou Viglione. His pointer, “A” — short for Adrian, as in “Yo, Adrian!” the line made famous by Rocky Balboa — was a bird dog, and an exceptional one. But she was a family dog, too, the constant companion of Viglione, his wife Rita, and their daughter Evelyn. Calm when she needed to be, playful when it was appropriate, endearing in ways large and small, “A” stole their hearts as a pup and never gave them back. As perfectly behaved as she was at home, however, “A” turned into a demon when she went hunting. She had a terrific knack not only for finding birds, but for pinning them, holding them by the force of her presence until Viglione arrived to flush and shoot. To his credit, he recognized that “A” was at her best when she was given her head and allowed to ramble some. In other words, she was, like most pointers, a bit on the “wide” side.

“I rarely got to see her make game,” Viglione recalls. “Most of the time, the bell would go silent, and I’d find her on point.”

He found her on point a lot during the course of their partnership. On their home grounds in Fairfield County, Connecticut, they “hit for the cycle” on no fewer than eight occasions, bagging grouse, pheasant and woodcock in the same day. This is no mean feat anywhere, but consider this: From a hilltop in Fairfield County, you can damn near seethe Manhattan skyline.

Mandy.

“A’s” bred-in-the-bone desire was never more apparent than during a New Brunswick woodcock trip that Viglione took with her breeder, Dr. James Alexander. Braced with her dam, field trial champion Carolina Holly, “A” disappeared into a grove of pines, where her bell went silent. Viglione spied the very tip of her tail peeking through the boughs, but as the men approached, “A” did a very uncharacteristic thing. She broke point. This puzzled Viglione — until a frenzied scuffle erupted a few yards farther on. The dog had pounced on a porcupine, and the more it hurt her, the more she wanted to hurt it back. She emerged from the fray looking like a pin cushion.

“There was blood all over her,” Viglione relates. “She had quills in her gums, her nostrils, even her eyeballs. I was terrified that she might lose an eye. Jim pulled the quills out, one by one, and it was obviously torture for her. He had some antibiotics in the truck, so we led her back, gave her a pill, and put her in her kennel so she could rest.

Few pointers have ever matched the desire of Lou Viglione’s “A.”

“But she didn’t want to rest. She went crazy when she realized that we were leaving her behind. I tried to tell myself it was the right thing to do, but it didn’t feel right. So I walked back to the truck. She’d absolutely destroyed her kennel, and I thought, ‘If she wants to hunt that badly, she probably should.’ Within a minute or two, she pointed a woodcock. She hunted like a champ for the rest of the day. I tell you, if people could function as well under adverse circumstances as bird dogs can, it’d be a hell of a world.”

“A” has been gone about a year now, mercifully put to sleep after a courageous battle with cancer. Viglione has been offered a new pointer pup, but so far the household remains dogless. “I’m just not ready yet,” he shrugs.

Golden Retriever

Athletes — and gun dogs, especially field trial dogs, are nothing if not athletes — are supposed to retire at the end of their careers, when age has eroded their ability to stay competitive. The difference, of course, is that while human athletes presumably make this decision for themselves, canine athletes have it made for them. People retire; dogs are retired.

Golden retrievers tend to be “thinkers,” which on occasion can result in a clash of wills between dog and trainer.

Which explains why a golden retriever named Topbrass Cotton was pensioned off in mid-career, literally at the peak of his powers. His record was impressive — he’d earned both his open and amateur field champion titles — but the relationship between Cotton and his owner! handler, Jeff Finley of St. Charles, Illinois, had deteriorated in the pressure-packed field trial environment. Things came to ahead at the 1983 National Open Retriever Championship. Cotton was firmly in contention going into the seventh series, a demanding quadruple water mark. He retrieved the first bird, a flyer, perfectly — and then the wheels came off. Goldens tend to be “thinkers” (as opposed to Labs, who are generally “doers”), and Cotton was no exception. He’d already decided, in his mind, which bird he was going to retrieve next. Unfortunately, it was not the same bird that Finley thought he should retrieve next. The clash of wills that followed has become the stuff of legend in retriever field trial circles. Cotton refused his handler’s command in a particularly creative and picturesque way, and Finley retired him on the spot. The dog was five years old.

That might have been the end of the story, were it not for Jackie Mertens, the woman who’d bred Cotton at her Topbrass Kennel in Elgin, Illinois. Eight months later, she cut a deal with Finley for co-ownership of the dog. She wanted to put him back on the circuit, but Finley was hesitant. “Cotton probably won’t run for you,” he told her. Mertens was persistent, however, and finally persuaded Finley to let her run the dog in five trials. If he performed well, they’d continue to campaign him; if he performed poorly, they’d retire him for good.

Goldens, like most gun dogs, are great athletes that keep on surprising you long after they’re supposedly retired.

The rest, as they say, is history. Cotton blossomed under Mertens’ tutelage, showing improvement every week. At the fifth trial, he won a doubleheader, getting the nod in both the open and amateur all-age events. Then, in the summer of1985, he achieved a measure of immortality by becoming the first and only golden to annex the National Amateur Retriever Championship. Although Cotton was rock-solid throughout the event, the ninth series, a fiendishly contrived triple water mark, was the one in which he separated himself from the rest of the field. On the longest of the three falls, Cotton “took a terrible line,” according to Mertens. “He started drifting, and I was a nervous wreck trying to decide if I should handle him or not. I knew that it would really hurt his chances if I handled him, but I was afraid that if I didn’t he’d end up on shore, and the judges would drop him.

“It was close — I don’t know how many times I almost hit the whistle – but Cotton stayed in the water, corrected on his own, and completed the test. Only one other dog, out of the 20 or so in the series, made it through without being handled.

“Of course, Cotton went on to be named champion — to the delight of nearly one thousand spectators. By the time his career came to a close in 1988, he’d amassed 274 all-age points, far more than any other golden, ever, and 11th on the all-time list. I honestly don’t think that there will ever be another golden like him.”

Retirement is not all it’s cracked up to be.

English Setter

Some dogs are remembered for what they won; others are remembered for how they won. And no dog ever won as spectacularly as Hillbright Susanna did. Or, for that matter, lost as spectacularly. Whether she placed first, second, third or finished out of the money entirely, at the end of the trial hers was the name on everybody’s lips. Perhaps the ultimate measure of Hillbright Susanna’s greatness is the fact that she was as unforgettable in defeat as she was in victory.

Like the great Hillbright Susanna, these setters share a good degree of the champions lofty style and tremendous bird-finding ability.

“Sensational” was a word often used to describe her along with “little.” She weighed just 30 pounds, but it was 30 pounds of dynamite concealed within the package of a black-ticked English setter. Tremendous bird-finding ability, awesome stamina, lofty style both running and on point — Hillbright Susanna had it all. But the quality that distinguished her most conspicuously was her speed. It was blinding, electrifying. “Fast as light;’ she was called. And yet, when “Dot” winded game, she could stop in the blink of an eye, swapping ends as suddenly as if the earth itself had reached up and grabbed her by the collar. Her personality sparkled, too. Little wonder, then, that even in an era replete with illustrious champions, Hillbright Susanna was the dog that people turned out to see. Listen to Earl Crangle, the man who developed Dot, the man in whose house she lived and in whose heart she lives:

“When Dot ran, you couldn’t find ahorse to ride anywhere. They were all rented out. The galleries loved her; I recall them on several occasions breaking out in applause when she had one of her brilliant finds. Even when she beat herself by making a mistake on her game, she never failed to thrill with her style, speed and class.

“Let me tell you, there has never been a dog like Dot. She wasn’t just the best setter I ever handled — she was the best setter I ever saw.”

And in a field trial career that spanned five decades and included hundreds of noteworthy wins, Crangle credits Dot for the memory he treasures most. The time was September 194 1; the place, the prairies near Pierson, Manitoba; the event, the All-America Club’s open all-ages take. After awarding first place honors to the pointer, Norias Aeroflow, the judges called back two dogs to compete head-ta-head for second. One was reigning National Champion, Ariel. The other was Hillbright Susanna.

On paper, it looked like a classic David vs. Goliath scenario: the diminutive setter against the big, imposing pointer; young Earl Crangle — “Not yet dry behind the ears;’ in his own words against the already legendary Clyde Morton, the leading handler of the day, if not of all time. Morton campaigned his pointers sparingly, grooming them for a handful of important trials — and ending up in the winner’s circle more often than not.

The showdown was set to occur, as showdowns generally do, at high noon. It was scorching hot, and just before breakaway Morton remarked, “I hope you’re carrying plenty of water, Earl. As hot as it is, that little setter’s going to need it.” Crangle drew himself tall in the saddle, looked his competitor straight in the eye and said,”Mr. Morton, that big pointer. “I’ll be needing water long before Dot does.”

With that, the judges ordered, “Turn ’em loose!” Both dogs raced ahead, and within minutes each had recorded sterling finds on “chicken,” as sharptails of the Canadian prairies are called. Like fighters trading punches in the middle of the ring, the gritty setter and the mighty pointer matched cast for cast, point for point. Everybody -the intent handlers and their scouts, the watchful judges, the murmuring gallery knew they were witnessing something extraordinary. No quarter was given, or taken, by either side.

Getting a good whiff.

But then, just as Crangle had predicted, Ariel started to wilt. His tongue lolled; his gait grew labored. There was a “bluff” — a popple thicket —half-a-mile away across the open prairie. It was a likely spot for birds, and both handlers hit their whistles, urging their charges on. But only Dot responded. Crangle may have been wet behind the ears, but he knew his dog, knew that when he called on her she would give him everything she had, and then some. She streaked for the bluff, where she slammed into one of those explosive points that were her trademark. Crangle flushed the chickens, and the judges had seen enough. “Hillbright Susanna second, Ariel third,” they announced.

“No one who saw that duel ever forgot it,” says Earl Crangle. But then, no one who saw Hillbright Susanna ever forgot, period. They’re old now, those men and women, but when they think of her their eyes glisten with the memories. For a few moments, they’re transported back, to a time when they were young, and a place where a setter flashed across the horizon, a setter who was fast as light.

Editor’s Note: This article originally appeared in the 1995 July/August issue of Sporting Classics.

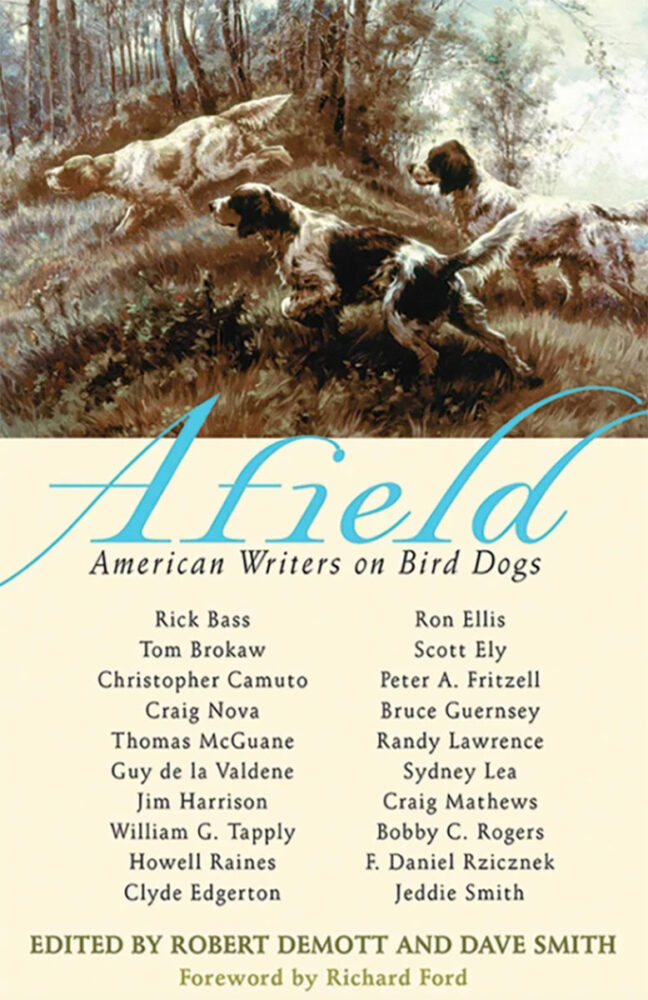

This marvelous collection features stories from some of America’s finest and most respected writers about every outdoorsman’s favorite and most loyal hunting partner: his dog. For the first time, the stories of acclaimed writers such as Richard Ford, Tom Brokaw, Howell Raines, Rick Bass, Sydney Lea, Jim Harrison, Tom McGuane, Phil Caputo, and Chris Camuto, come together in one collection. Buy Now

This marvelous collection features stories from some of America’s finest and most respected writers about every outdoorsman’s favorite and most loyal hunting partner: his dog. For the first time, the stories of acclaimed writers such as Richard Ford, Tom Brokaw, Howell Raines, Rick Bass, Sydney Lea, Jim Harrison, Tom McGuane, Phil Caputo, and Chris Camuto, come together in one collection. Buy Now